|

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the Coaches vs. Cancer program by NCAA basketball coaches:

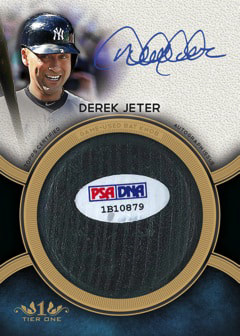

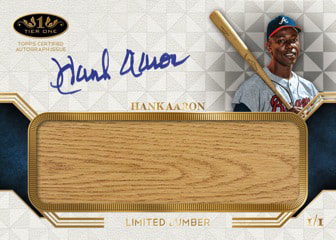

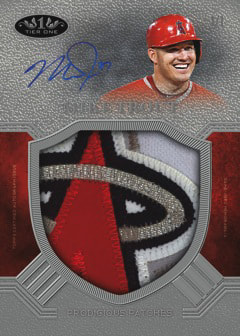

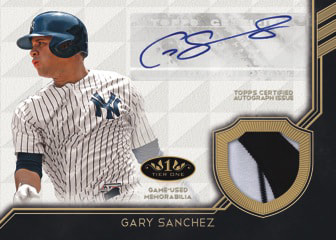

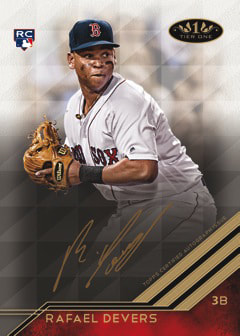

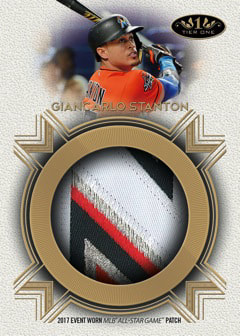

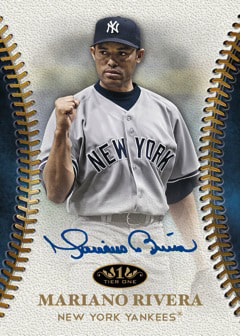

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/ncaa-coaches-donating-sneakers-as-part-of-battle-against-cancer/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the May 2018 release of Topps Tier One baseball:

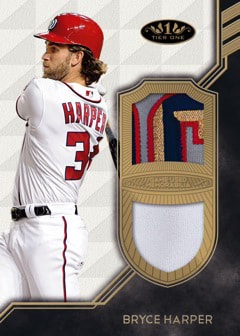

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-tier-one-baseball-returns-with-many-autograph-relic-options/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2017-2018 Upper Deck SP Game Used hockey set, which will be released Jan. 17:

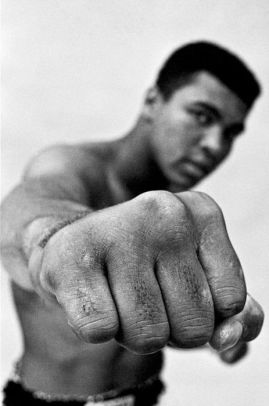

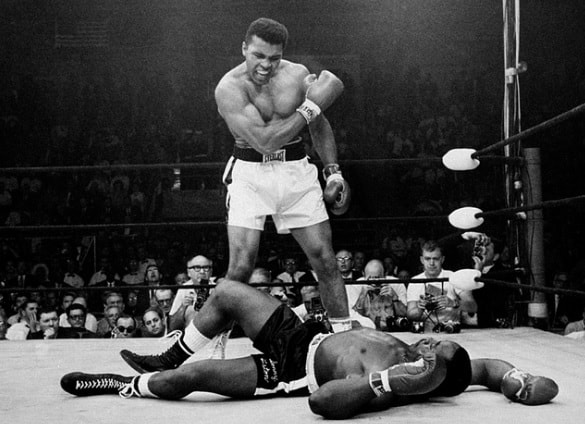

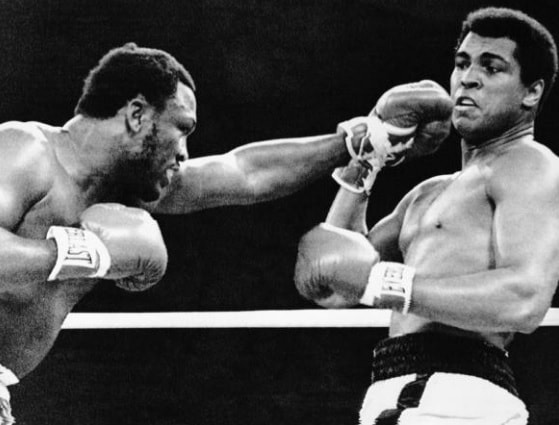

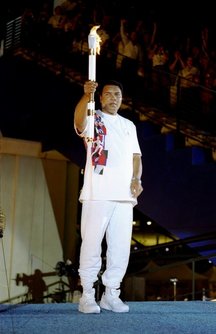

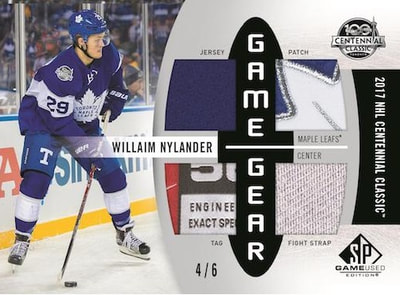

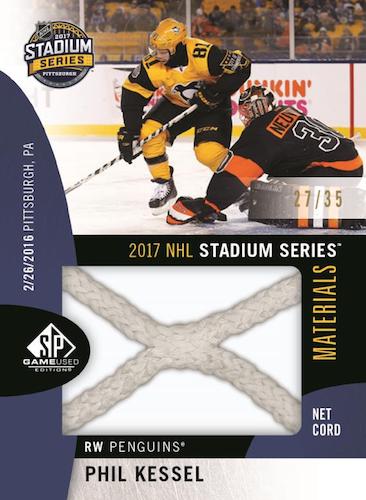

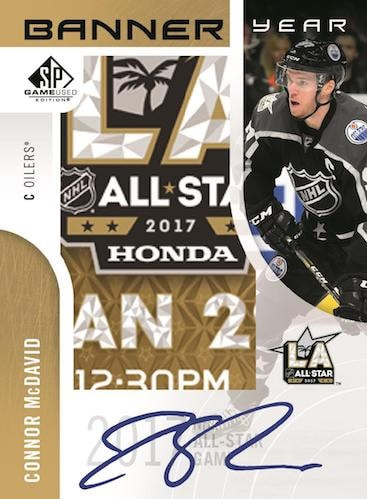

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-18-upper-deck-sp-game-used-hockey-preview/  Jonathan Eig is a talented researcher and a gifted storyteller. He has the journalist’s ability for sifting fact from fiction, a scholar’s knack for digging beneath the surface, and a novelist’s eye for detail. That’s a good thing, because Eig needed every bit of his ability to write a well-crafted biography of Muhammad Ali. He succeeds because he blends all those elements together in a smooth narrative backed with solid research. In Ali: A Life (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $30; 623 pages), Eig devoted four years to researching and writing about the life of the former heavyweight champion. It’s a big task, because Ali was more than a sports figure. He was a lightning rod for protest when he refused induction into the military to fight during the mid-1960s. He was a defiant black athlete who demanded justice for his race. And he had a magnetic personality, extravagant tastes, and an insatiable sexual appetite. Ali was “the wittiest, the prettiest, the brashest,” Eig writes. “Sunshine with a snappy left jab.” He also was a threat to the establishment, scaring old-school sportswriters and politicians. Ali, Eig writes, was “a phenomenon, a spirit, an attitude, a challenge to democracy and decorum.” In the most revealing line in this 623-page work, Eig delivers the knockout punch about Ali, who died in 2016. “He was the fist in the white man’s face,” Eig writes.  Muhammad Ali stands over Sonny Liston after their second fight in 1965. Muhammad Ali stands over Sonny Liston after their second fight in 1965. Eig conducted six hundred interviews with more than 200 different people including sessions with Ali’s second and third wives and other family members. His sources include thousands of pages of FBI and Justice Department documents, hundreds of books, and thousands of newspaper and magazine clippings. He also took advantage of taped interviews of Ali by Sports Illustrated writer Jack Olsen. Eig’s research paid off when he uncovered the details about the murder conviction of Ali’s grandfather, Herman Clay, in 1900. And more intriguingly, Eig enlisted the help of CompuBox, Inc., researchers, who watched every one of Ali’s fights and counted the punches he threw and the ones he absorbed. That gives Eig’s descriptions of Ali’s fights an authoritative tone that few writers can approach. When Eig writes that Ali was hit more than 200,000 times during his career, you believe it. Discussing the first fight between Ali and Joe Frazier, in which each boxer received $2.5 million, Eig noted that “Only in America could such wonders occur.” “Only here could the great-grandsons of slaves each earn $2.5 million for a night of work,” Eig writes, noting that it was more than baseball Hall of Famer Hank Aaron made during his 23 years in the major leagues.  Joe Frazier, left, handed Ali his first professional loss as a fighter in 1971's "Fight of the Century" at Madison Square Garden. Joe Frazier, left, handed Ali his first professional loss as a fighter in 1971's "Fight of the Century" at Madison Square Garden. This follows the same pattern Eig has followed in his previous four books: Bludgeon readers with research, and then soothe them with elegant prose. Eig has said that he followed the advice of fellow biographer Robert Caro, who told him to ask the people he interviewed what it was like to be in the same room with the subject, to probe for the little details that gave the reader a fuller picture. That was the same philosophy he used in his other works, starting with Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig in 2005. Two years later he dug into the debut season of Jackie Robinson in Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. Eig’s next two books were outside sports, with Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted Gangster in 2010; and The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution, in 2014. Young Cassius Clay learned how to box in his native city of Louisville, and won Olympic gold in the 1960 Summer Games. In 1961 he was exposed to the teaching of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, and he would embrace that religion for the rest of his life. Clay attended meetings of the radical sect and would adopt the name Muhammad Ali shortly after defeating Sonny Liston for heavyweight champion in 1964. Interestingly, when Ali wanted to return to boxing after his conviction because he needed the money, Elijah Muhammad “punished” him by expelling him from the Nation of Islam for a year and symbolically taking away his name. Ali “had given up his first wife for his religion,” Eig writes. “He had changed his name, risked prison, sacrificed millions of dollars, and turned his back on his friends and relatives. “… And now the man who had inspired Ali’s actions, the man he worshiped as a prophet of God, was casting him aside … It must have been bewildering.”  Ali regained the heavyweight title by defeating George Foreman in 1974's "Rumble in the Jungle" in Zaire. Ali regained the heavyweight title by defeating George Foreman in 1974's "Rumble in the Jungle" in Zaire. Eig’s writing style is in full force here. Many of his sentences are long phrases, tumbling along over commas as he ventures from thought to thought. But it is an effective device, because Eig uses these phrases to drive home a point. It is a literary version of a flurry of punches, which gets the reader’s attention in a hurry. Ali demanded respect, preened and postured about his greatness, and tried to get under the skin of his opponents. He did not find it wrong to have sex with prostitutes before a big match, and did it at least twice, Eig writes. Eig’s blow-by-blow accounts of Ali’s fights are descriptive and telling. In his first fight against Joe Frazier, Ali “was acting like a kid on a playground sticking out his tongue and taunting his enemy.” But Frazier was wise to that act; when he began pummeling Ali toward the end of the fight, it “was as if Ahab had discovered his great white whale lying on the beach and waiting to be carved up.” Ali lost that fight, but stunned the boxing world three years later when he defeated George Foreman in Zaire. Ali went against conventional wisdom and dared Foreman to hit him with his best shots while he retreated to the ropes. The “rope-a-dope” strategy worked, and Ali used lightning combinations in the eighth round to regain the heavyweight title. “He had turned himself into a sponge, absorbing his opponent’s energy,” Eig writes.  There was one more great fight left in Ali’s tank, and that was his third fight with Frazier — the “Thrilla in Manila.” Ali was merciless in the weeks leading up to the fight, comparing Frazier to a gorilla and questioning his ability and intelligence. Frazier was fed up. “I mean it,” he told his trainer, Eddie Futch. “This is the end of him or me.” Eig’s narrative of the fight is almost as compelling as the bout itself. “When (Ali) should have been exhausted … no, when he was beyond exhausted. He maintained a pace that defied not only the heat but also logic and perhaps physiology,” Eig writes. “And Frazier, practically blind, caught them flush.” When Eig writes that Frazier “stomped forward like an apparition,” he has captured the essence of the fight and the toll it took on both fighters. He should have walked away after that bout, secure in the knowledge that he was a great fighter, but Ali sounded like a man who was “sacrificing his health and reputation for the pursuit of the next paycheck.” The final stages of Ali’s life saw him become an ambassador for peace while he battled the effects of Parkinson’s disease. Twice, he went to the Middle East to help negotiate the release of American hostages. In a riveting scene, Ali lit the torch to open the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. No other American athlete was as recognized worldwide as Ali, so the scene was equally poignant. When Ali died, he was a revered figure, even by some who once had reviled him. He was a complex man, whose bombastic style made him a polarizing figure. After winning the gold medal in Rome, he saw a bright future. “Man, it’s gonna be great to be great,” he said. Ali was great outside the ring, as Eig demonstrates. “He had made people think, made them angry, made them reimagine what a young black athlete could say or do,” Eig writes. Eig’s well-researched biography has the same effect. It is a thought-provoking look at an iconic figure. There is no need to put the title of the book on the cover. A photo of one of boxing’s greatest lords of the ring suffices. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

| Bob D'Angelo's Books & Blogs |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed