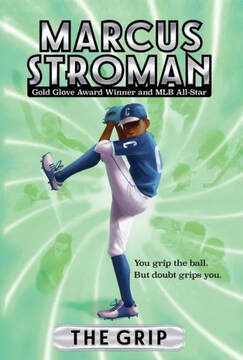

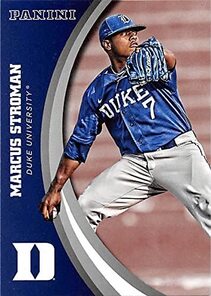

In The Grip (Aladdin Books; hardback; $17.99; 208 pages), Stroman, 31, gives the reader a gentle but firm reminder that young people are facing a tremendous amount of pressure to succeed and to “fit in” — in school, among their peers, and in athletics. Mental health should be a priority in today’s turbulent times, but it is discussed only when a tragedy occurs.

Mass shootings by teens have become disturbingly prevalent and point to mental health issues — at Uvalde, Texas, where an 18-year-old entered Robb Elementary School and killed 21 people last year; at Parkland, Florida, where a 19-year-old opened fire at a Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, killed 17 students and staff members and injured 17 others; and Littleton, Colorado, where two teens killed 13 and wounded more than 20 at Columbine High School in 1999.

And most recently, the case of a 6-year-old bringing a gun to school in early January 2023 and wounding a first-grade teacher at Richneck Elementary School in Newport News, Virginia.

Stroman’s book is not that heavy, but it carries a message that is uplifting and powerful: Mental health is the key to success on and off the field. Sure, that success may not be perfect, but it is a great building block.

The Grip is loosely based on Stroman’s personal experience. At 5 feet, 7 inches tall, Stroman has always faced skeptics who did not believe he had the mettle to succeed. But he overcame the odds and has compiled a 67-67 record in eight seasons with the Toronto Blue Jays, New York Mets and the Chicago Cubs.

Stroman runs his own foundation, Height Doesn’t Measure Heart, which provides the necessary encouragement for youngsters to realize their dreams.

And dreams are what fuel young Marcus in The Grip. He’s a star pitcher for his team and knows he has the physical tools to play baseball at a high level. It is the mental part that worries him, and the book shows Marcus dealing with plenty of doubt. And he does not want to talk about to those closest to him.

In the narrative of The Grip, Marcus and his sister are “ping-ponging” between their divorced parents’ homes. His father catches him daily, ramping up the pressure for the young pitcher to excel. A colleague on his team, James, is constantly needling him about his short stature. And an upcoming baseball “assessment” is messing with his mind.

That is a lot to put on any young athlete’s plate, especially when, as a pitcher, he is trying to consistently find the plate.

THE GRIP! First of a three-book volume with @simonschuster. Beyond excited to help the minds of young kids. Focuses on how to navigate adversity! Mental health and the ability to keep going…is the key to life. Pre-order now. In stores on 1/31/23! https://t.co/5DjePN5Z6f pic.twitter.com/Rtx75fduXR

— Marcus Stroman (@STR0) November 7, 2022

In the book, James’ digs about his height really get to Marcus. Had he been able to look into the future he would have seen that height does not necessarily matter. Recently, he has made it to the majors, and left-hander Tim Collins, who pitched for the Royals (2011-14), Nationals (2018) and the Cubs (2019), is 5-7.

Southpaw Bobby Shantz stood only 5-6, but he went 119-99 from 1949 to 1964, won eight Gold Gloves and was the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1952 with a 24-7 record and a 2.48 ERA.

By the way, the shortest pitcher of the modern era was Dennis John “Ginty” Gearin, who stood 5-4 and pitched for the New York Giants in 1923 and 1924.

Marcus’ support group in The Grip includes his older sister Sabria, his grandmother and a group of friends that include Danny, Jordan and Kai (Stroman’s real-life son, also named Kai, was born in 2022). But the stress about the upcoming assessment is causing him to withdraw.

“I’ve never asked myself that before. And I’ve never wanted to run in the opposite direction of my dreams, until now. What is happening?”

Marcus concedes that he does not want to fail at something everyone believes he can do.

Marcus’ parents and coaches can see he is struggling. And let’s be honest. Kids at the middle age level are going through changes. They are between cute elementary school students and moodier high schoolers. It is a difficult transition. The timid children are easily bullied, and the level of cruelty is real and unfiltered.

It was rough when I was in middle school (we called it junior high school) in 1969 and 1970. It is much tougher now, now that social media is available. Stroman believes that, too, and stresses the importance of every child having a support group.

“I feel like a lot of the time in this world, especially with social media, there’s so many people who work against you. Or there’s so many ways that you can give in to people and not allow yourself to truly chase what you want to do in life,” Stroman told the Sun-Times. “So I think it’s extremely important to keep a small group of people who love you and who are going to support you.”

In the book, Marcus’ mother is one of those support people, along with his father, sister and grandmother. She recognizes his need to get away from baseball for awhile, so she organizes a rest day for him and his sister. They go to the pool, relax and eat hot dogs.

But James does not know that and remains baffled, to the siblings’ great delight.

Because he is still stressing about the assessment, Marcus is encouraged by his mother to visit a “mental-health coach.” And he confesses his real fear: “Everyone believes in me and says I can do it. Everyone believes in me except for me. I’m scared that maybe this time I can’t pull it off.”

With guidance and encouragement from his support group, Marcus does indeed do well at the assessment and even strikes out his nemesis, James.

This is the only part of the book that is confusing. Marcus gets James to foul off two pitches and then misses with a pitch he believes should have been strike three. Then he throws another strike, but the at-bat continues.

“It feels like I’ve been on the mound for an hour,” Marcus thinks to himself. Well, for at least three strikes, anyway.

OK, the sequence is confusing, but the final result is what is important.

And Marcus even comes to a truce with James afterward, which is a nice touch.

In real life, Stroman believes in the mental approach to the game. According to SportsNet New York, his former teammate at Duke University, Mike Seander, introduced him to the 1994 book by Deepak Chopra, “The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your Dreams.”

“It settles me, calms me, gets me where I need to be, reminds me to keep my life in perspective,” Stroman told Newsday in August 2019. “It goes with me everywhere.”

The Grip is a book that should be carried around by youths. It is an uplifting story and one that encourages kids to believe in themselves.

As Stroman notes, standing tall is not physical, but a state of mind.

“If you can believe in yourself, you can do anything,” he writes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed