Since joining the New York Yankees as a raw rookie in 1951, Mantle had been anointed as the next great Yankee, the player who would carry on the tradition of greatness set by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio.

Mantle had shown flashes of brilliance, with tape measure home runs and the speed to beat out drag bunts or flag down long fly balls at Yankee Stadium. He had helped New York win four pennants in his five seasons, but there had been this nagging feeling that Mantle had not tapped into his vast potential.

That changed in 1956, when Mantle won baseball’s Triple Crown and led New York to a comeback World Series victory against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Mantle looked the part of a hero — blond, crew cut, heavily muscled, the prototype of the All-American Hero. But he was a flawed hero, and the media did a good job of hiding it in 1956.

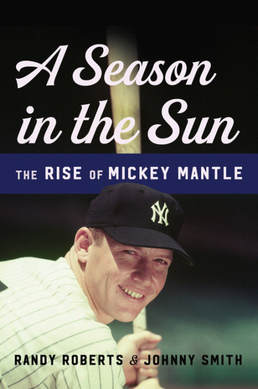

Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith take a fresh look at Mantle in the context of the 1950s in their latest book, A Season in the Sun: The Rise of Mickey Mantle (Basic Books; hardback; $28; 277 pages). It was true that the times dictated that sportswriters only covered what took place between the foul lines, and that was a blessing for Mantle, who was not shy about taking a drink or enjoying the company of women.

“With the help of the very best sportswriters in New York,” Mantle emerged “as an American icon,” the authors write.

Mantle had that alliterative name that “evoked power and poetry, arousing the kind of admiration reserved for baseball immortals.”

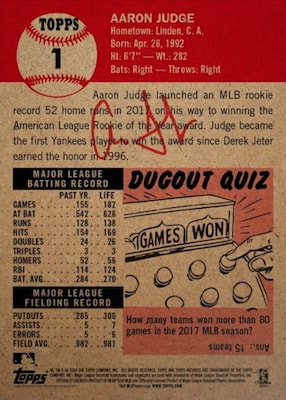

And 1956 showed Mantle at his powerful best. He hit 52 home runs and drove in 130 runs while scoring 132. He batted .353 and had a .705 slugging percentage with 188 hits and 376 total bases. All were career highs except for home runs (he’d hit 54 in 1961).

Roberts and Smith take a different approach with Mantle. There have been plenty of books written about the Yankees slugger, and many of them point to his excesses, particularly his drinking habits, which led to his death in 1995 after he had cirrhosis of the liver and needed a transplant to stay alive. Cancer and hepatitis C also sapped his strength and vitality.

The authors concede the vices and diseases that led to Mantle’s death, but that approach “ignores much of the joy of his life.”

“To fully understand the man, his impact on baseball, and what he meant to America, it is necessary to look at his life as he lived it,” Roberts and Smith write, “not as a study in retrospection.”

That’s why they decided to visit Mantle as he was in 1956, when he was at the peak of his career. Mantle was beginning to blossom in 1955, leading the American League in homers (37), triples (11), walks (113) and slugging percentage (.611). Excellent numbers, but Mantle was injured toward the end of the season and had little impact in the World Series, playing in only three games and going 2-for-10 as the Yankees lost to the Dodgers in seven games.

Roberts and Smith wanted to answer three questions about Mantle: How did he become a hero? Why did it happen in 1956? And what did he mean to America?

Men sang his praises, and Mantle managed an aw-shucks duet with singer Teresa Brewer in her 1956 song, "I Love Mickey."

Both Roberts and Smith have the credentials to answer those questions.

Smith earned his bachelor’s degree at Michigan State University in 2004 and earned his master’s two years later from Western Michigan. He received his doctorate in 2011 from Purdue. He and Roberts collaborated on the 2016 book, Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X.

The authors’ bibliography is extensive, tapping into such diverse sources as Leonard Shecter, Glenn Stout, Dick Schaap, David Falkner, Peter Golenbock, David Halberstam, Jane Leavy, Ben Bradlee Jr., Richard Ben Cramer, Roger Kahn, Bill James and Jules Tygiel. That’s just a sampling. The footnotes are extensive and rich in detail, which is what would expect from a pair of college professors.

Their research was deep, too, as they combed newspaper records in the National Archives to get a fuller, richer picture of Mantle. They tell a wonderful anecdote by comedian Billy Crystal, who was at Yankee Stadium the day Mantle cracked a home run that nearly became the first fair ball hit out of the park. Only the façade in the right field upper deck prevented the ball from bouncing on the streets.

Roberts and Smith answer their three questions by noting that Mantle “dramatized the daily struggle” for individual goals. He was a symbol of what was good about America — young, strong, vigorous, clear-eyed. That it happened in 1956 was due to a few changes Mantle made in his batting stance, particularly standing deeper in the batter’s box. Mantle’s chase of Babe Ruth’s home run record — for much of the season he was far ahead of the pace the Bambino had when he 60 in 1927 — also fired the imagination of baseball fans.

Mantle was unable to sustain that pace, particularly in September, but he still became the first Yankees hitter since Ruth to hit 50 homers in a season.

The narrative for A Season in the Sun is smooth and builds tension through several subplots. There was the resurgence of Ted Williams, who threatened to spoil Mantle’s Triple Crown year by challenging for the American League batting title. A youthful Al Kaline challenged Mantle in the RBI race. Today’s baseball fan is aware of performance-enhancing drugs, but few in 1956 realized the extent of the usage of Dexedrine, or “greenies,” to keep players alert and “up.”

Then there was the World Series, where Mantle only hit .250 with six hits, but three of those hits were homers. One homer was the first hit in Game 5, which gave the Yankees a 1-0 lead. Mantle did excel on defense, making a lunging, back-handed catch of a Gil Hodges line drive in left-center field at Yankee Stadium that preserved Don Larsen’s perfect game.

The book's title, A Season in the Sun, is reminiscent of two memories from the 1970s. It is the title of a 1977 book about a college baseball team by noted author Roger Kahn, and a variation on the 1973 song by Terry Jacks, “Seasons in the Sun.” Kahn’s book was sunny, while Jacks was singing a depressing collaborative song, with lyrics written by poet Rod McKuen and a tune composed by Belgian songwriter Jacques Brel that was originally titled “Le Moribond.”

In 1956, Mantle had joy and had fun, and a great season in the sun. Through excellent research and a conversational narrative, Roberts and Smith show that joy Mantle experienced.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed