That makes them very good storytellers. Jim Brosnan began the trend in 1960 with The Long Season, followed by Jim Bouton’s epic Ball Four a decade later. You can put Skip Lockwood into the same category. Lockwood, who played for six teams during his 12-year major-league career, may not break new literary ground in his autobiography. But he sure tells some great stories.

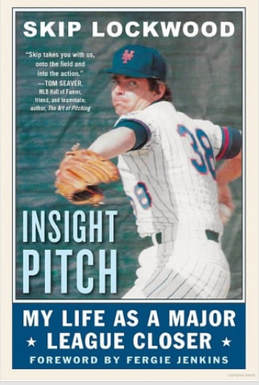

In Insight Pitch: My Life as a Major League Closer (Sports Publishing; hardback; $19.99; 229 pages), Lockwood is disarming and descriptive, weaving firsthand stories about an infielder-turned-pitcher who was “not good enough to be a star, not bad enough to headline a trade.”

Claude “Skip” Lockwood is now 71, and his stories about his years in the majors are fresh and funny. Lockwood began his career with the Kansas City Athletics in 1965, then played for the Seattle Pilots, Milwaukee Brewers, California Angels, New York Mets and Boston Red Sox. He spent the bulk of his career with the Brewers (1970-1973) and the Mets (1975-1980) and earned 65 of his 68 career saves while pitching in New York as the team’s closer.

Lockwood later earned a master’s degree in science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and concentrated on sports psychology. Being a reliever was the perfect foundation for his later education, because in baseball “it seemed like I stood at the brink of disaster daily.”

And it was difficult to stare down those difficulties when your glasses constantly fogged up, as Lockwood relates in several humorous episodes. He brings the reader onto the pitching mound, into the bullpen and into the clubhouse.

While he was unable to help turn a double play as a young infielder, Lockwood does manage to turn a few good phrases in Insight Pitch. Slugger Dave Kingman, for example, slid into second base “looking like a ballerina in a batting helmet.”

As a rookie, Lockwood got a baptism of fire his first day in the batting cage, as an Athletics coach named Babe hit him several times and later started a fight with the 17-year-old. While Lockwood does not give the batting practice pitcher’s last name, he is referring to Babe Dahlgren, the man who replaced Lou Gehrig at first base when the Iron Horse’s consecutive games playing streak ended in 1939. Lockwood notes that Babe “was the first major-leaguer to fail a drug test,” which is inaccurate. Dahlgren was rumored to have smoked marijuana and in 1943 became the first major-leaguer to take a drug test. He underwent a battery of tests to prove he did not have marijuana in his system, a story New York Times columnist Murray Chass repeated in 2007. Still, Lockwood accurately portrays Dahlgren as a bitter, angry former player who could never shake the rumors about his past.

At times, one gets the impression that Lockwood was a baseball version of Forrest Gump, sharing locker rooms and experiences with men like Satchel Paige, Jesse Owens, Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver, Yogi Berra and Don Mossi (I can never pass up a chance to mention the bushy-browed, large-eared reliever known as “The Sphinx”).

Lockwood’s story about getting the upper hand in negotiations with Athletics owner Charlie Finley is humorous and shows the negotiating savvy he would need during the 1970s when he was the Brewers’ player representative.

Lockwood even had a brush with Bouton when both were with the Pilots. In Ball Four, Bouton quotes Lockwood asking, “hey Jim, how do you hold your doubles?” after a game where the struggling knuckleballer allowed several two-base hits.

“Hate to lose a funny guy,” Bouton wrote after Lockwood was sent to the minors in 1969.

Speaking of funny, Lockwood tells about a prank pulled on him by Mets clubhouse manager Herbie Norman. When Lockwood came to the Mets, he arrived during a game and had to get to the bullpen fast. Norman was more than accommodating, whisking the new reliever to the outfield bullpens at Shea Stadium. Lockwood began shaking hands with his new teammates until the bullpen coach yelled at him for mingling with the wrong team. Norman had dumped the Mets’ new pitcher into the opposition bullpen — on purpose.

“Sorry, kid,” Norman said later. “I couldn’t resist.”

Lockwood points to the influence of Cleveland Indians trainer Nelson Decker, who helped him succeed through mental imagery. “Picturing and imagining became a discipline and a language to me,” he said. What he allowed and controlled in his thought processes would have a big impact in his pressure-cooker role as a closer.

Lockwood opens his book with an anecdote about throwing at a batter’s head when he was a Little League pitcher, and ends it with a poem, where he says that “My actions on the field turned out to be nothing more than dreams believed.”

“Baseball connects the dreamer and the dream,” he concludes. “Part hope … part real … part magic.”

Insight Pitch helps the reader experience a player’s dreams and the magic of making it to the major leagues. Certainly, there was heartbreak along the way, but in Lockwood’s case it was a fascinating ride. And he turned those experiences into a fascinating read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed