http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1952-berk-ross-set-overview/

|

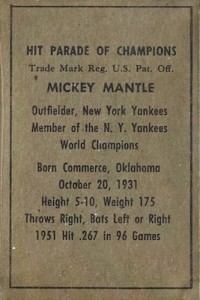

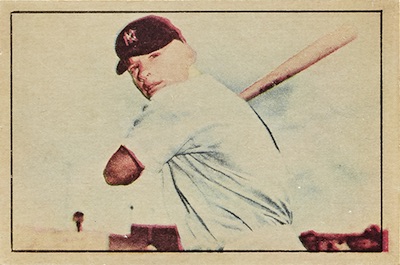

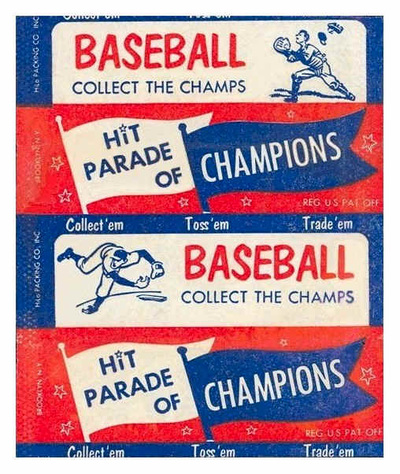

Here's a story I did for Sports Collectors Daily 0n the 1952 Berk Ross baseball set: http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1952-berk-ross-set-overview/

0 Comments

As families and friends gather and enjoy this Thanksgiving weekend, it’s important to remember why we are thankful. In Alan Charles’ case, he is thankful just to be alive. And after reading his gut-wrenching, chilling autobiography, it’s even more amazing that he is alive. But the former University of Tampa pitcher has overcome a lot of pain, sorrow, addiction and broken relationships — some of it admittedly self-inflicted — and has a more positive outlook on life. Charles, now 56, lays it all out in the open in the introduction to “Walking Out the Other Side: An Addict’s Journey from Loneliness to Life” (SJC Publishing; hardback; $24.99; 308 pages). “This book is an honest look through my eyes about my journey through life,” he writes. And quite a depressing look at times, although Charles did have some highlights. Charles’ 24-year addiction to cocaine ruled his life, ruined his career, wrecked his family life and nearly killed him. At times, after reading Charles’ stories, the reader has to shake his head and wonder, “how is this guy still alive?” Indeed, after Charles fell asleep at the wheel after a drug-induced evening and totaled his car, the men who towed his wrecked vehicle away said the same thing when Charles came to claim his personal effects.  Charles’ downward spiral began when he was nine. His father died of an apparent heart attack while on the road — years later, Charles learned he had actually committed suicide. That left him with his “checked out mother” and “crazy broken brother.” His brother had been hit by a car two months after his father’s death and never fully recovered, becoming a “nightmare patient” at home. That led to a difficult home life where Charles “lived each day of my life in a dysfunctional environment.” Seeking an outlet, Charles began playing organized baseball and showed some talent as a pitcher. “Playing baseball was my first drug,” he writes. Harness racing was his other love. Introduced to the sport as a teen, he eventually competed in the sport. But baseball came first, and after his college career ended at the University of Tampa, Charles played professionally in the Dominican Republic. Former Reds pitcher Pedro Borbon took him under his wing and Charles had some success, but not enough to make it to the major leagues. He had other highlight moments, too. He helped work the sideline during Super Bowl XVIII in Tampa, introduced the Bangles at a concert in Connecticut, and was invited onstage to sing “I Can’t Smile Without You” with Barry Manilow (Charles was a big fan). He even managed to return to sports, working as a batting practice pitcher for the New York Mets. But it was cocaine — his “friend” — that would dominate Charles’ life for more than two decades. He was introduced to it by a friend in Connecticut during a period where Charles and his girlfriend were having relationship problems. The effect from snorting the coke was “as if someone had waved a magic wand over me” and relieved his stress and anxiety. “I’d never felt anything like it, and it was the greatest feeling in the world,” Charles writes. “From that point on, I was in.” The addiction soon spiraled out of control, and Charles was pushed into rehabilitation. He soon became bored with it. To him, there were two kinds of people in rehab — those who “pretended to want to get better” and those “committed to rationalizing their addictions.” Charles fell into the second group. He managed to function successfully as a salesman selling advertising, got married and fathered two children. But Charles was never far away from cocaine, and it nearly destroyed him. Then he decided to beat the habit once and for all. “Cocaine was the friend who could make all of my troubles and worries disappear, at least temporarily,” Charles writes. “Now I was on my own, left to my own devices. “It was both lonely and scary.” It was difficult, but Charles has stayed clean. He was able to repair his family issues and reconnect with his two daughters. And he realized how he’d been playing Russian roulette with his life each time he snorted cocaine. “It takes a great deal of humility and courage to remove the mask we hid behind for so long,” Charles writes. “We used to believe that the mask protected us, but it turned out it was killing us, by keeping us apart from the rest of the world.” Charles originally believed that cocaine was a door that led to forgetting about his troubles. In “Walking Out the Other Side,” he shows how persistence, faith, humility and focus can bring a man back from addiction. It’s a courageous book, and while it has a positive ending, it’s not a feel-good story. Charles is blunt and does not sugarcoat his life, hoping that his experience might discourage others from following that drug-laced path. He’s thankful to be alive to tell the tale. Here's a story I wrote for Smack Apparel about memorable NFL Thanksgiving games:

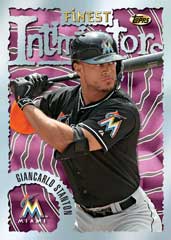

http://www.smackapparel.com/2015/11/26/thanksgiving-football/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Topps' announcement about the release of its Finest baseball product in June:

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-finest-baseball-set-june-release/ Here's a story I did for Sports Collectors Daily about Topps planning to release Tier One baseball in May 2016:

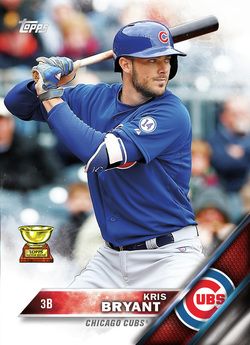

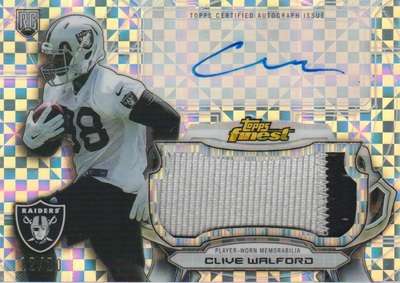

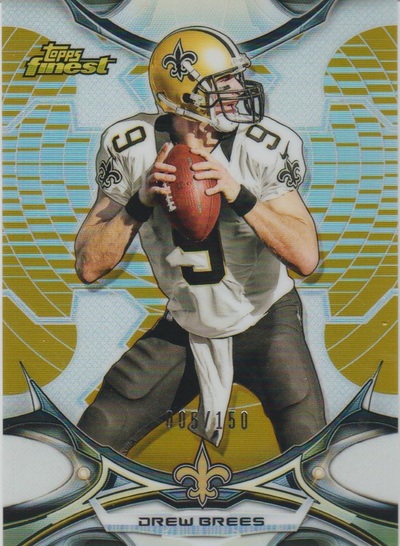

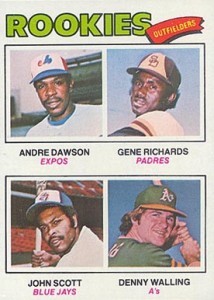

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-tier-one-baseball-returning-may/  I’ve said it many times — pro wrestlers are the best storytellers. It started in 1974 with Joe Jares’ classic book, “Whatever Happened to Gorgeous George?” Since then, there have been books written by Mick Foley, Ric Flair, Terry Funk, Chris Jericho, Lex Luger and Bret Hart — to name but a few. They tell some great stories about life on the road, ribs, swerves, works, shoots and kayfabe. But Scott Teal is the best interviewer of pro wrestlers. Hands down. Since 1996, he has published 53 issues of the newsletter, “Whatever Happened To …?” and has authored books with pro wrestlers like Ole Anderson, Tony Atlas, Don Fargo, J.J. Dillon and Stan Hansen. Teal knows the sport, has an uncanny ability to put the wrestlers at ease and prompts them to speak in great detail about their lives and careers. It’s pure gold. And “The Wrestling Archive Project: Classic 20th Century Mat Memories, Volume 1” (Crowbar Press; Paperback; $22.95; 406 pages) is golden. In Teal’s words, he is doing what he has enjoyed more than anything in the wrestling business — “conducting in-depth interviews with the legends.” Teal is promising that each volume will contain two or three new interviews, along with 10 from the “Whatever Happened To …?” series. The first volume contains an interview that has to be classified as a main event. For the first time, former wrestling heel Buddy Colt opens up about his career and the plane crash in Tampa Bay south of downtown Tampa that ended it and took the life of Bobby Shane in 1975. The interview with Colt is 117 pages and covers every part of his long career. It’s also the first time Colt has given a detailed account about the plane crash, which also impacted the careers of Mike McCord (later known as Austin Idol) and manager Gary Hart. Colt did give a few quotes for a Tampa Tribune story on February 1, 2015 — and the story was a good narrative — but Teal’s interview provides much more detail and puts the reader in Colt’s head as he tried to land safely. Fans of “Championship Wrestling From Florida” during the 1970s will enjoy the back-room stories Colt tells, and all the big names are mentioned — Eddie Graham, Jack Brisco, Louie Tillet, Paul Jones, Johnny Walker, Don Curtis, Hiro Matsuda and the Great Malenko — the interview reads like a who’s who of the golden age of Florida wrestling. Colt always had a humorless, all-business persona in the ring — he portrayed a ruthless heel who included a taped thumb to the throat of babyfaces in his arsenal of tricks — but his sense of humor comes out in his interviews with Teal. On wrestling Sonny the bear in Oklahoma City, Colt cracks that “it was really pretty easy.” “In fact, the bear was easier to work with than Tim Woods,” he said. Teal also includes fresh interviews with Adrian Street and referee Mac McMurray. The McMurray interview is another highlight of the book, giving readers a perspective of the business from a referee’s point of view. His stories are funny, too. He had a memorable night in 1972 driving Andre the Giant south on Interstate 95 toward Miami. McMurray was just south of West Palm Beach when Andre wanted some beer. McMurray went into a convenience store and bought “two king-sized Budweisers.” “He looked at them, looked at me, looked back at them and said ‘Wait here.’” McMurray told Teal. “He went into the store and came back out a minute later with a case of Budweiser for him and a six-pack for me. “Before we got down to the exit for the Miami airport, he had one beer left and I still had three left of my six-pack.” The other highlight of this compilation is Teal’s February 2001 interview with “midget wrestler” Lord Littlebrook. He got his start in the circus (where he peeled potatoes) and later married “a six-foot Dutch girl.” Littlebrook gives a unique view of the sport and notes that he was “friends with just about everybody” in the wrestling business. “I don’t think, in all my years in the business, that I ran across five people that I didn’t like,” he tells Teal. Filling out the volume are interviews from the past with Gene Dundee, Dandy Jack Donovan, Lou Thesz, Dick Cardinal, Benny McGuire, Pepper Gomez, Gorgeous George Grant, Frank Martinez, Gene Lewis, "Hangman" Ernie Moore and Joe Powell. There were two glitches I found in the Buddy Colt interview. The first involved a caption that asserted that the Opa-locka Marine air base was in Jacksonville, when in fact it is in Miami-Dade County. The second was a mention of the benefit event given by Jody Simon at the old Fort Homer Hesterly Armory in Tampa (now called the Tampa Jewish Community Center & Federation). The event is listed in the interview as taking place July 11, 2015, when it fact it was held on June 11 — the day that longtime Florida wrestling star Dusty Rhodes died. Throughout “The Wrestling Mat Archive Project,” the warmth and passion of the wrestlers come through. “When you like your job, it’s not a job, and I loved my job,” Colt said. “We had so much of ourselves as people invested,” McMurray tells Teal. Consequently we were rewarded. We gave and gave and gave and the people responded. “It was a good feeling.” Investing in this first volume of wrestling memories should give fans a good feeling, too.  Topps Finest football remains consistent in what it offers collectors. Refractors, autographs and different colored parallels, along with a 150-card set, makes Topps Finest challenging to complete but easy if you’re just building a set. A hobby box consists of two mini boxes. Each mini box has six packs, with five cards to a pack. I received a mini-box to review, and there were 20 base cards. The big card in the mini-box was an autographed jumbo relic card of Raiders tight end Clive Walford. The card was thick, and while the autograph was on a sticker, the swatch was a generous size and had two colors. Parallel cards include refractors, which fall two per mini-box. Blue refractors are numbered to 250, and there also are gold (numbered to 150), red (99), diamond (60), BCA (25) and STS (10). Superfractors and Printing Plates are 1/1 cards. I pulled a refractor card of the Saints’ Jimmy Graham, and a red refractor of Bills wide receiver Sammy Watkins, numbered to 99. There also was a gold parallel of Saints quarterback Drew Brees, numbered to 150. An X-Fractor appears once every eight packs, and I pulled one of the Patriots’ Rob Gronkowski. I also pulled a pair of die-cut cards. One was an Atomic Blue Refractor Rookie Die-Cut card of Cardinals running back David Johnson, numbered to 299. There was a second die-cut card of Chargers running back Melvin Gordon. The design for Finest is straightforward. An action shot of the player is set against a shiny background on the card front. The card back includes statistics and a paragraph touting the player’s achievements from last season. That consistency is something longtime collectors of the set will enjoy.  “Long time ago when we was fab.” George Harrison was singing about his days with the Beatles all those years ago, but San Francisco 49ers fans can relate. They long for the days of cool — Joe Cool. The days when Joe Montana was leading the 49ers to four Super Bowl titles — the NFL’s version of the Fab Four, if you will — are long gone, and the team is sitting in the NFC West cellar this season with a 3-6 record. But San Francisco fans — and others who watched Montana play—will get a new perspective about the Hall of Fame quarterback thanks to Keith Dunnavant’s new biography. “Montana: The Biography of Football’s Joe Cool” (Thomas Dunne Books; hardback; $26.99; 326 pages) is a brisk, focused look at a quarterback who remains the gold standard of signal-callers. Other quarterbacks had better passing statistics and better form, but few delivered as consistently in the clutch ass Montana. The project spanned four years, and Dunnavant buttresses his narrative with research and lively interviews with friends, teammates, coaches and family members. That’s not surprising. Dunnavant’s books include biographies of Bart Starr (“America’s Quarterback” in 2011) and Bear Bryant (“Coach” in 1996), and “The Missing Ring,” (2006), which focused on the undefeated 1966 Alabama football team. Dunnavant himself is a good story. As a 14-year-old, he talked his way into becoming the sports editor of a small weekly paper in Athens, Alabama. There must be something magical about towns named Athens; in Athens, Georgia, a 15-year-old named Edwin Pope became sports editor of the Banner-Herald in 1943. Pope later became the longtime sports editor at the Miami Herald. Dunnavant went on to work at the National in 1981, and also wrote for Sport magazine and Adweek. He also founded four magazines and wrote for two decades about college football. In “Montana,” readers will read about the familiar and legendary successes: “The Catch,” which rocketed the 49ers into their first Super Bowl; and the winning drive he engineered in Super Bowl XXIII to defeat the Cincinnati Bengals. Who else could look into the huddle, with 92 yards to cover and barely three minutes to play, and casually remark to nervous teammate Harris Barton, “Look! Isn’t that John Candy?” That exchange is legendary and gets full throttle in “Montana.” But what sets this biography apart are Dunnavant’s tales of Montana’s early career and his running battles with his high school coach (Chuck Abramski) and college coach (Dan Devine), both who seemed unsure of their quarterback’s ability. Even Bill Walsh, the 49ers coach who created the West Coast offense that Montana executed to perfection, sometimes seemed to lack confidence in his star. But that’s what fueled Montana. He had a desire to take his doubters words and shove them back down their throats. He didn’t do it with talk; Montana produced on the field, and engineered some amazing comebacks in college and in the pros. He was a competitor in his own right, and he benefited from a tough, demanding father who guided his young career.  Keith Dunnavant spent four years researching and writing "Montana." Keith Dunnavant spent four years researching and writing "Montana." Before Super Bowl XIX, a major story line was the impending quarterback battle between the veteran Montana and Miami’s young star, Dan Marino. From an East Coast perspective, Montana was barely mentioned (certainly, Montana got better play west of the Mississippi), but he turned the tables on his young rival, beating the Dolphins with his arm and his feet—plus his ability to call a mistake-free game. Dunnavant also deserves kudos in his narrative about Super Bowl XIX to note that Marino shifted to a no-huddle offense late in the first quarter. I’ve seen very few reports of that game that mentions that fact, and while it worked at first, San Francisco’s defense adjusted and made life miserable for Marino. But the 49ers’ victory and Montana’s near-flawless day demonstrated what fueled him. “Time after time, he had been doubted, dismissed as too ungifted, too small, too fragile, too inconsistent, too this, not enough that, to become a successful quarterback,” Dunnavant writes. “He always looked so calm and centered … but beneath the surface, he was a tenacious competitor with a burning desire to win who desperately wanted to be respected, pursuing not just championships but some larger validation.” Even after establishing himself, a back injury and the presence of Steve Young waiting in the wings as an impatient backup quarterback kept Montana on edge. But it also spurred him to greater things. “The arrival of Steve Young stirred something deep inside Montana, empowering him to churn resentment into determination,” Dunnavant writes. “The presence of a talented rival breathing down his neck, ready to step in at any moment, was just what he needed to propel him toward a whole new level.” “Montana” ends on a wistful note, as Joe Cool is enshrined in Canton and finally mends fences with the high school football coach who had downplayed his talents for so many years. Dunnavant displays a nifty touch throughout this biography, weaving Montana’s personal successes and failures with his spectacular college and pro career. It’s a refreshing look, and it will remind 49ers fans of when their franchise was truly fab.  Topps announced its 2015 MLB All-Star Rookie Team today, and the Chicago Cubs grabbed three of the top spots. Third baseman Kris Bryant, second baseman Addison Russell and outfielder Kyle Schwarber were the Cubs’ representatives. Earlier this week, Bryant was named the National League Rookie of the Year. This year’s American League Rookie of the Year, Astros shortstop Carlos Correa, also made the Topps squad. Topps has been naming rookie teams since 1960. The Topps Rookie Cup is awarded to one player at each position, a right-handed starter, a left-handed starter, a reliever and — for only the second time — designated hitter. The N.L. champion New York Mets placed pitcher Noah Syndergaard and outfielder Michael Conforto on the Topps squad, while the Miami Marlins also added two players — catcher J.T. Realmuto and first baseman Justin Bour. Others making the team were outfielder Randal Grichuk (Cardinals), DH Miguel Sano (Twins), left-handed pitcher Carlos Rodon (White Sox) and reliever Roberto Osuna (Blue Jays). Past winners of the Topps MLB All-Star Rookie Team include MVP winners such as Buster Posey, Ichiro, Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan and Cal Ripken Jr. Eighteen former winners have been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Here's a story I wrote for Smack Apparel about sporting events that would have gone viral had the Internet existed back then:

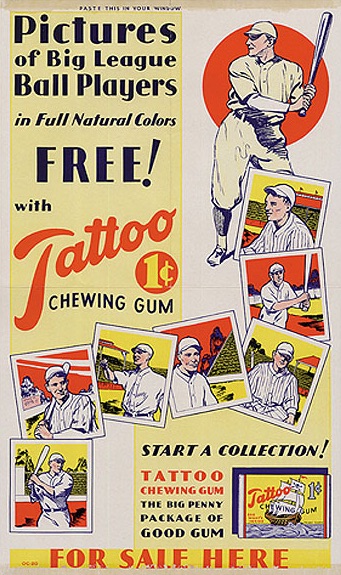

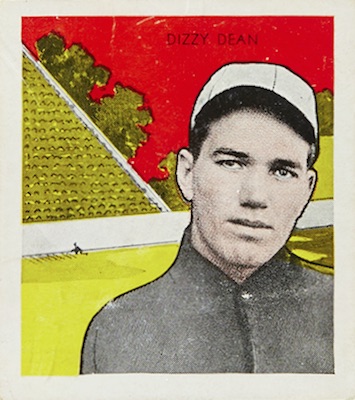

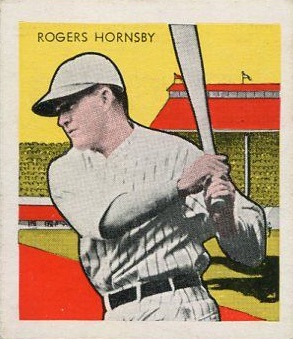

http://www.smackapparel.com/2015/11/19/history-sports-broken-internet/#more-1841 Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1933 Tattoo Orbit baseball set. It's a 60-card set that includes 17 Hall of Famers and is a challenging, underrated product to collect:

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/tattoo-orbit-offers-collectors-a-reasonable-challenge/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1966 Topps Rub-Off inserts.

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1966-topps-insert-rubbed-collectors-the-right-way/ Here's a story I did for Sports Collectors Daily about the rookie cards of those Hall of Famers who won rookie of the year honors. I chose five of the more affordable HOFers' cards:

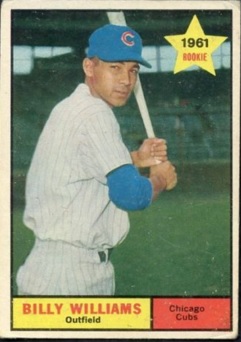

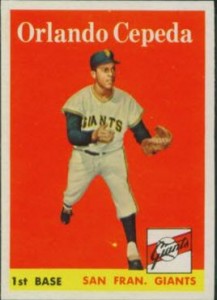

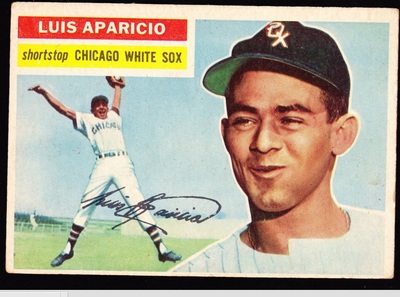

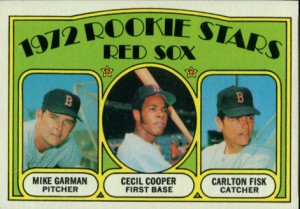

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/notable-roy-winners-have-affordable-rookie-cards/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1954 Bowman football card set:

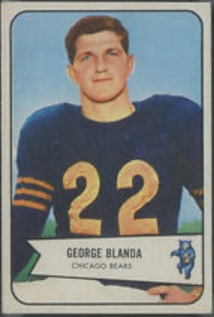

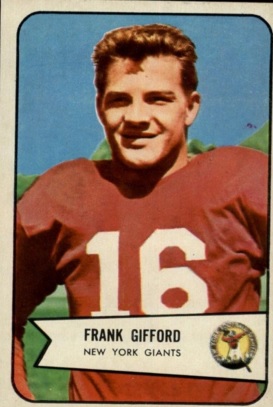

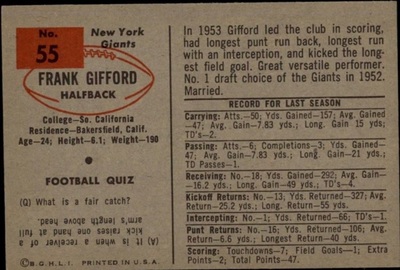

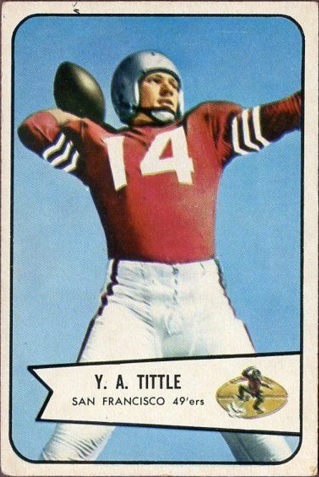

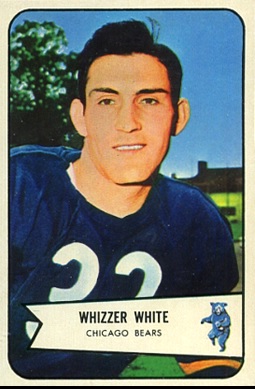

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1954-bowman-football-had-a-catchy-design/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an SCP Auctions sale that includes the items of Carl Shy, who won a gold medal playing basketball in the 1936 Olympics.

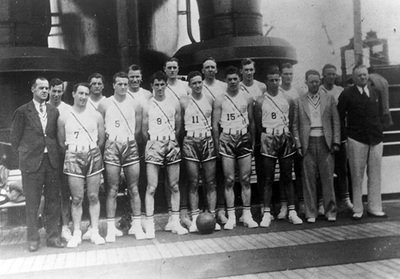

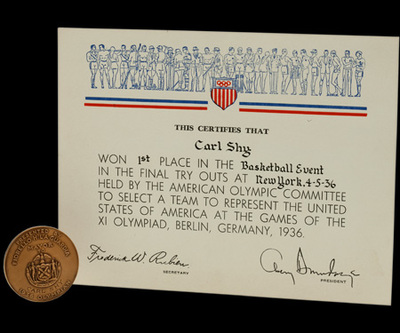

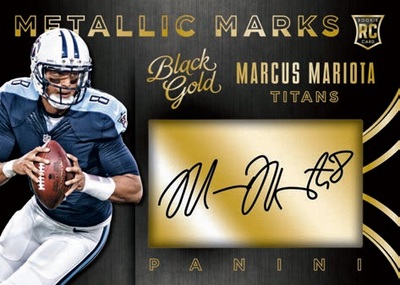

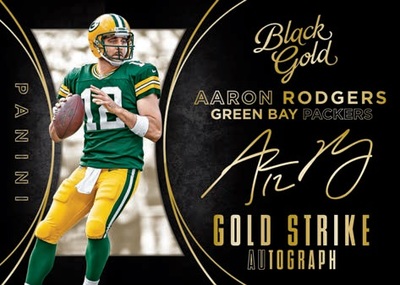

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/hoop-history-1936-olympic-basketball-gold-medal-at-auction/ Here's a link to a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily, previewing Panini America's Black Gold football. It's scheduled for a January release:

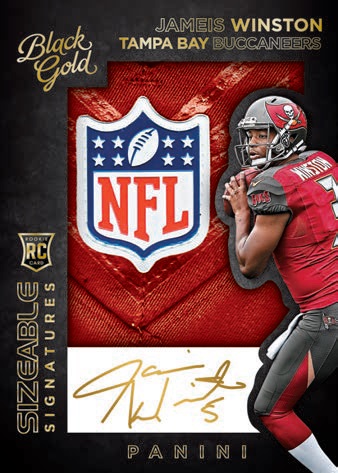

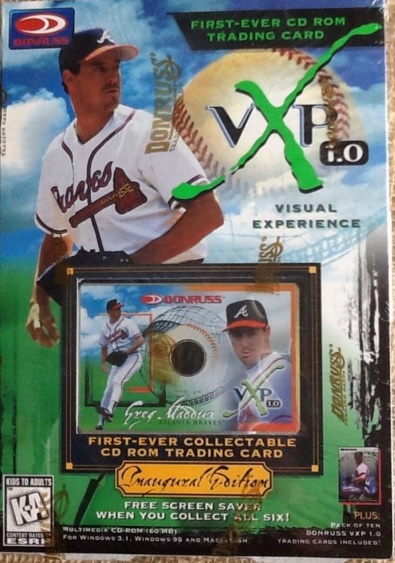

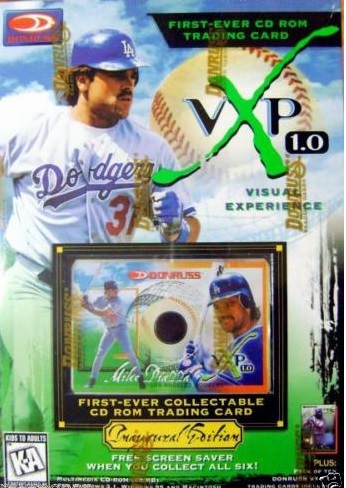

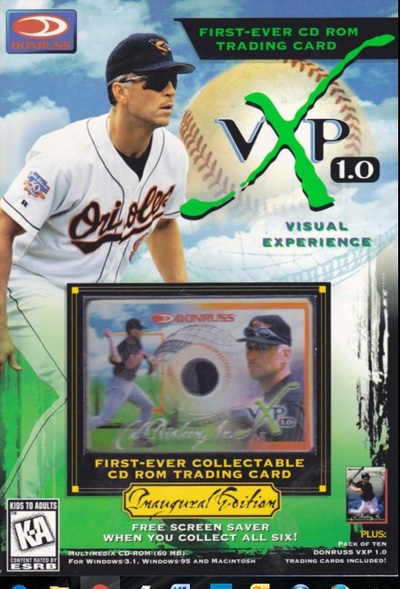

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/panini-black-gold-football-to-have-more-on-card-autos/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the dawn of interactive sports card, spurred on by the 1997 Donruss VXP 1.0 CD ROM.

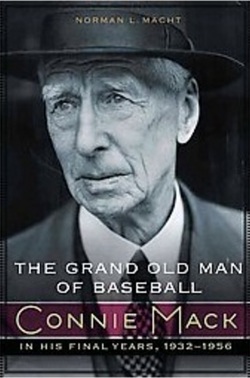

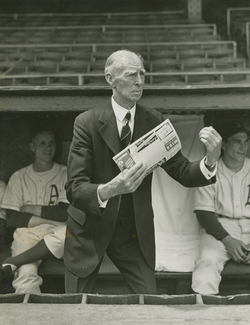

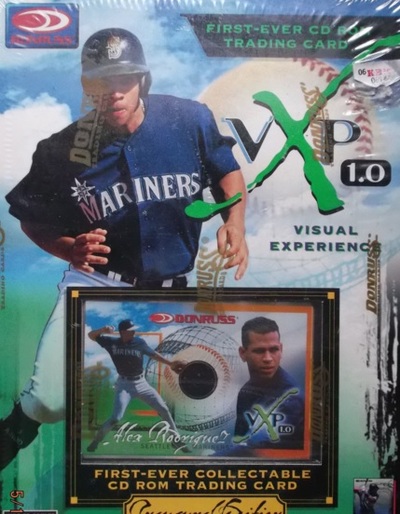

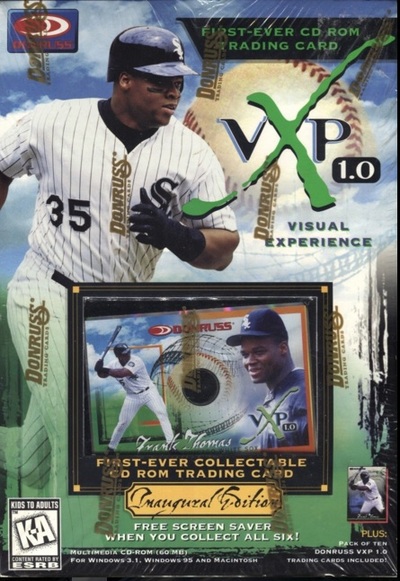

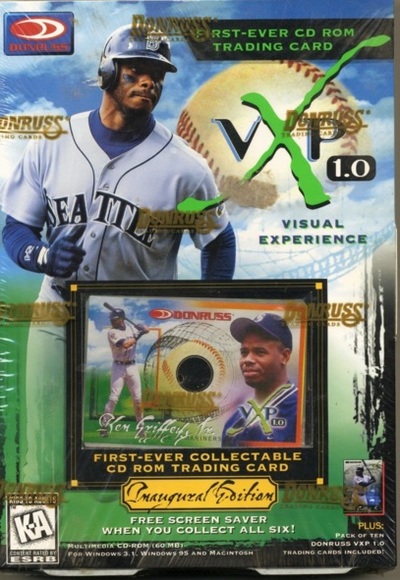

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/interactive-infancy-1997-donruss-vxp-1-0-cd-rom/ Here's a story I did for Sports Collectors Daily about an Arizona card dealer and his Facebook followers, who helped build a 1975 Topps set for a young collector from Kansas.

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/stolen-1975-topps-set-leads-to-act-of-kindness/  Norman L. Macht completes his massive, deeply researched and fascinating biography of Connie Mack with the third and final volume. After 30 years of researching, interviewing and writing, what Macht originally thought would be a 350-page work turned into “a 2,000-page trilogy.” The baseball community should be grateful. Macht, a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, turned 86 on August 4. He ends his biography of Mack with a flourish, with “The Grand Old Man of Baseball: Connie Mack in His Final Years, 1932-1956” (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 624 pages). This finale follows Volume 2 — “Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915-1931” — which was released in 2012 and spanned 720 pages. The first book — “Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball” — was 742 pages and was published in 2007. Macht conducted interviews, and researched newspapers from Philadelphia, Washington, New York, Chicago, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He also interviewed Connie Mack’s children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews. “The Grand Old Man of Baseball” covers the final 24 years of Mack’s life, when the Great Depression forced him to break up the team that had dominated the American League from 1929 to 1931.  Macht takes a positive, yet unsparing look at Mack, who navigated the Philadelphia Athletics during a barren period that spanned the Depression, World War II and even into the Korean War. Macht picks up the story in 1932, the year after the Athletics would appear in the World Series for the final time during the franchise’s time in Philadelphia. Baseball readers have been conditioned through the years by articles such as “Mr. Mack,” written by Bob Considine in the August 9, 1948, edition of Life magazine. It was a warmly written feature that referred to Mack as “the Mr. Chips of baseball,” delighting fans with his gentle whimsy. Mack himself massaged the legend with his 1950 book, “My 66 Years in The Big Leagues.” Macht debunks some of those myths about Mack. For all of his courtliness, Mack had a temper and was not averse to swearing on occasion. He was not always a favorite of umpires, either, having his son Earle go out and bring them to the dugout to discuss a call. “Mr. Mack was a nice gentleman,” umpire Ernie Stewart said, “but he was not the saint that everyone has painted him to be.” And despite his reputation as a skinflint, Mack could be generous at times, writing checks to players during the season for outstanding performances. Or, just to be kind. Tom Ferrick was the Athletics’ top reliever in 1941, going 8-10 with seven saves and a 3.44 ERA. Placed on waivers after the season, Ferrick was claimed by Cleveland. Later that fall, Mack asked Ferrick to meet him at his office. “‘Young man,’ he said to me, ‘when we signed you we didn’t give you any money. We made $7,500 from Cleveland for you. I want to give you something for yourself.’” Mack handed Ferrick a check for $1,000. “He didn’t have to do that,” Ferrick recalled. To be sure, Mack was a tough negotiator at contract time, and economics prevented him from paying high salaries. He was up front about it with his players, and many seemed content to receive a slight bump in pay as opposed to nothing at all. After all, baseball player salaries were higher than the general worker made. Macht details some of the reasons why Mack missed parts of some seasons. In 1937, for example, he missed the last 34 games of the season due to a “stomach disorder,” which could have been a gall bladder attack. That condition flared up again in 1939, limiting Mack to only 62 games in the dugout. Many observers, including Mack himself, believed this second condition would prove fatal — but once again, Mack rebounded and would manage for another decade, saying that “the doctor says I’m good for many more years.” But Mack’s workload, enormous even for a younger man, would take its toll. “Connie Mack was either selectively deaf or acutely stubborn,” Macht writes. “His body was yelling at him to quit trying to do the work of four men. “But it was speaking a foreign language.”  Connie Mack managed the Athletics until he was nearly 88 years old. Connie Mack managed the Athletics until he was nearly 88 years old. Macht peppers his work with year-by-year summaries and dig up some interesting facts. For example, in 1945 the Athletics were forced to play 42 doubleheaders, including a mind-boggling 11 in 17 days late in the season. He writes about the Athletics’ surprising run at the 1948 pennant, and how Mack believed that he managed for one season too many (1950), because he was losing control of his faculties and his players. Macht also outlines the marital difficulties between Mack and his second wife, Katherine. At times, the couple lived apart, and after Mack’s death, Katherine took a photo of her husband and thrusted it at their son, Connie Jr. “Take that out of here,” she said. One of the more fascinating parts of this book was the sale of the Athletics to Arnold Johnson and the eventual shifting of the franchise west to Kansas City. Macht provides rich detail about the inner workings of the deal, and how Mack’s oldest sons — Roy and Earle — argued and feuded among themselves. But they were in alignment against their younger half-brother, Connie Jr. “Roy and Earle, though having little use for each other, were allied against Connie Jr., the only one with any rapport with the players and the Shibe Park employees,” Macht writes. “He had more ideas in a week than Roy or Earle had had in thirty years.” The chapter titled: “The Sale of the A’s: A Mystery in Four Acts” is a blow-by-blow description of backroom meetings, double-crosses and fraternal sniping. “Neither Roy nor Earle had been honest and aboveboard in everything each had said and done,” Macht writes. “Their public statements seemed to reflect more of a priority to be contrary to each other than to honor their father’s wishes or the fans’ interests.” Macht’s research is outstanding, although a few minor points emerge. He refers to Jimmie Foxx as “Jimmy” throughout the book, a curious deviation coming from a man who in 1991 wrote a book called “Jimmie Foxx” from the Baseball Legends series. Although, to be fair, Macht also referred to Foxx as “Jimmy” in his second volume. Macht also makes a reference to Fort McKinley at one point, where surely he meant Fort McHenry since he was writing about “bombs bursting in air.” “The Grand Old Man of Baseball” is a lively, descriptive and poignant end to the career of Connie Mack. He managed in 7,755 games, including 7,466 with Philadelphia from 1901 to 1950. He won nine American League pennants and went to eight World Series (his first pennant in 1902 predated the Series by a year), winning five of them. But in the end, Macht writes, “the measure of Connie Mack’s life is not the number of pennants or games won and lost but the lasting effect he had on the men he managed and the minds and hearts of those whose lives he touched.” Mack’s effect was far-reaching. So, too, is Macht’s treatment of Mack’s career. Have a great Veterans Day. Remember that those men and women who served helped preserve your freedom.

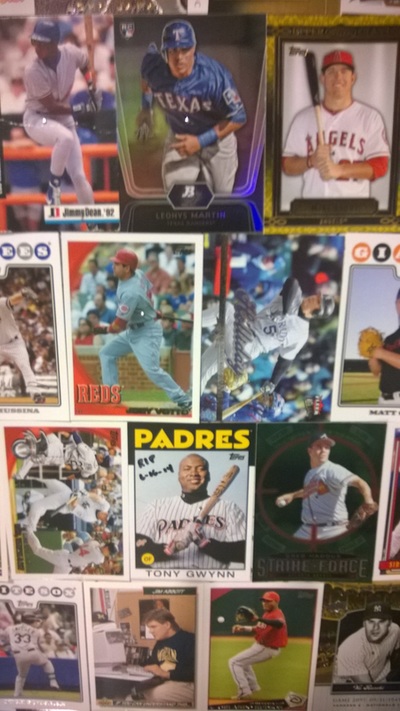

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Dustin Samms, a rabid Reds fan from Charleston, West Virginia, who has converted his basement ceiling into a baseball card shrine:

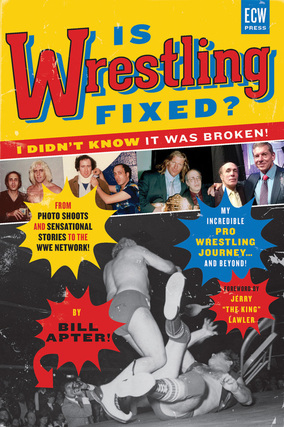

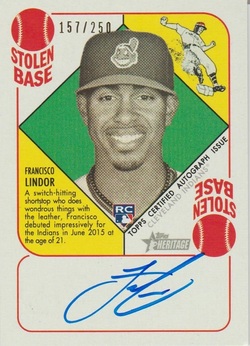

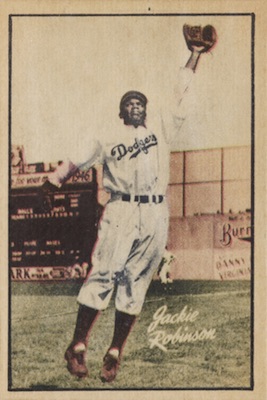

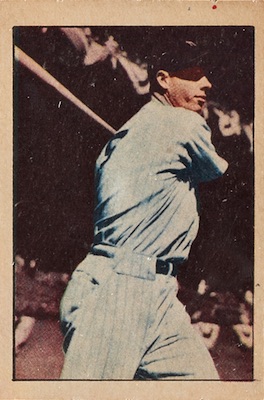

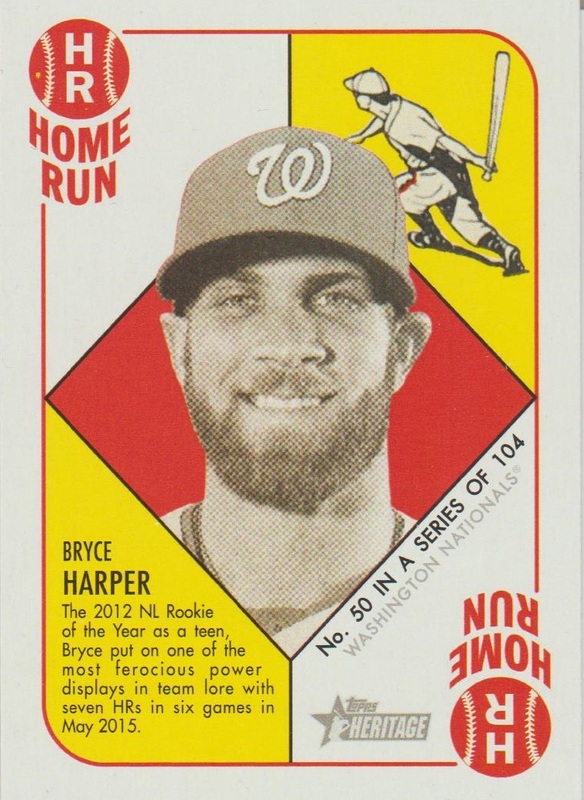

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/basement-ceiling-helps-collector-pinpoint-card-obsession/  I’ve always said that the best storytellers are professional wrestlers. Long hours on the road, squabbles with promoters and dealing with overzealous fans have produced some excellent wrestling books. Mick Foley, Ric Flair, Bret Hart, Chris Jericho and Terry Funk have put out some great books about life in and around “the squared circle. Add Bill Apter to the mix. Apter, who has covered pro wrestling for more than four decades, has written a bubbly, funny, sentimental and insightful memoir that takes the reader behind the scenes in the dressing rooms. “Is Wrestling Fixed? I Didn’t Know It Was Broken: My Incredible Pro Wrestling Journey … and Beyond!” (ECW Press; paperback; $19.95; 282 pages) is a collection of Apter’s memories as a writer and photographer. There is really no structure to the book; it’s basically a hodgepodge of memories from the Bruno Sammartino era of wrestling to today’s glitzier, big-production efforts. “I wanted to make a book that you could just pick up and dip into,” Apter writes in the prologue to the book. As a kid, I remembered Apter. He was the guy that did the photo spread in one of the wrestling magazines in 1973 (it was either “The Wrestler” or “Inside Wrestling”), challenging the veracity of Stan Stasiak’s notorious heart punch. And then there’s Apter, crumpling to the ground after taking the devastating hit to his chest. Of course, kayfabe was still intact during the 1960s and ’70s, so even though it looked real, the photo shoot was staged. Ah, those wrestling magazines. The ones that boasted cover photos of wrestlers whose faces were “crimson masks” (a nod to longtime wrestling commentator Gordon Solie), and headlines like “Bobby Heenan’s Bloody Obsession.”Apter’s memories of the Stasiak incident come early in his book. Apter’s working relationship with his boss, Stanley Weston, are informative and gives the reader an insight to the publishing business in the 1970s. Before the Internet and social media, Weston’s magazines were a way for wrestling fans to stay in touch with the top performers, the feuds and the title changes. Wrestling territories were still relevant in the 1970s; Apter was the guy whose columns and photographs put the reader right next to the ring apron. It was Weston’s advice to Apter that helped define him as a wrestling journalist. “What I want you to do is write the way you talk,” Weston told Apter. “I want the reader to hear your voice.” It was sound advice. Because of that, a generation of fans respected Apter’s credibility, and he has grown into an icon of the business. You’re not going to find much dirt in “Is Wrestling Fixed?” Oh sure, there are episodes where he ran afoul of promoters like Vince McMahon Sr. and Fritz Von Erich. Readers can find out why “Macho Man” Randy Savage wanted to kill Apter, and how Don Curtis got a young Apter (then a wrestling fan in New York), kicked out of a wrestling arena for being underage. Apter also recalls about writing about a wrestler who had died, only to discover that the grappler (Bearcat Wright) was quite alive several months later. Readers will enjoy Apter’s campy, goofy antics as the creator of Championship Office Wrestling, where “Wonderful Willie” defended his title against all comers. The COW belt was an integral part of “Apter’s Alley.” “I am simply amazed when I think about who has challenged me for the COW belt over the years,” he writes, tongue planted firmly in cheek. One of the nice parts of “Is Wrestling Fixed” is the chapter about the night Sammartino lost the WWWF title to Ivan Koloff. Apter was tipped off to the match’s result, and “it was my first ‘I have to kayfabe this’ moment of my career,” Apter writes. There are plenty of photographs in the book, but unfortunately none of the ones that defined his career. Those photos are owned by the wrestling magazines he worked for, so they were not included. That’s a shame. Apter writes about his colleagues in the magazine business, and has an amusing chapter about “Apartment Wrestling,” a cheesy fad that pitted scantily clad women wrestling in an apartment. You know, drop kicks over the couch and figure four leglocks on the carpet. An aside: a good friend of mine enjoyed Apartment Wrestling, so when he got married in 1981, I sent away for some of the magazines to present to him at his bachelor party as a gag. Everybody got a good laugh, but I got put on a mailing list, and you can just imagine the literature I received for the next year. My mailman was smirking. Apter gives the reader a behind-the-scenes look at the “feud” between comedian Andy Kaufman and wrestler Jerry “The King” Lawler. Kaufman accompanied Apter to his apartment and talked incessantly about wanting to wrestle. Apter contacted Lawler, who was amused. “You’ve got Andy Kaufman, the guy from ‘Taxi,’ in your little, roach-infested apartment in Queens?” Lawler asked. The resulting feud changed the landscape of professional wrestling. Apter also chronicles his adventures photographing boxing stars like Muhammad Ali and discusses his work as editor at 1wrestling.com. If you’re a fan of pro wrestling, “Is Wrestling Fixed?” is a must read. Apter has had an amazing career as a writer and photographer, and his stories are warm, funny and entertaining.  Topps goes back to its roots with the release of the 2015 Topps Heritage '51 Collection Baseball set. The 1951 Topps set resembled a card game and was released in two versions — 52 red back cards and 52 blue backs. Cards measured 2 inches by 2 5/8 inches, and the red backs were the more common version. Like the original product, the 2015 version is a pretty straightforward set. This year’s model is a premium factory set, with 104 base cards — 52 red backs and 52 blue backs. Price will be in the $75 to $85 range, depending on the seller.  The design is true to the original, with a black-and-white photograph of the player at the center of the card. Each box will contain a complete, 104-card set, 21 mini parallels and an autograph. The box I opened contained this breakdown of parallels: 10 red backs, five blue backs, three green backs, two black backs and a gold back. The mini parallels, by the way, are the same size as the original 1951 cards. The autograph was an on-card signature of the Indians’ Francisco Lindor, numbered to 299. The autograph was bold, if not terribly legible. Autograph parallels will feature blue backs, numbered to 25; green backs (10), black backs (5) and 1/1 gold backs. The 1951 set is overshadowed by its more baseball-oriented cousin in 1952 — and it should be. But it was still a unique look at baseball players. The 2015 Topps Heritage ’51 Collection recaptures that look.

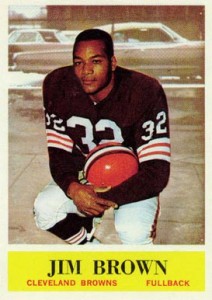

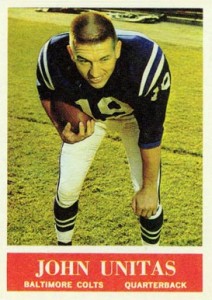

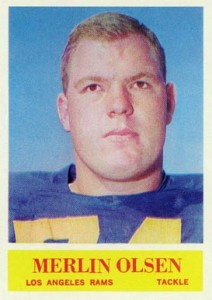

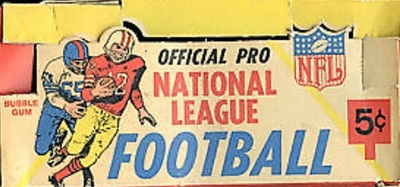

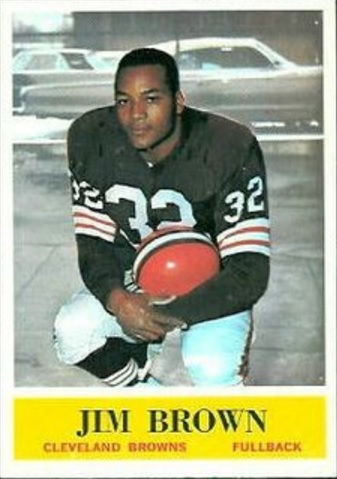

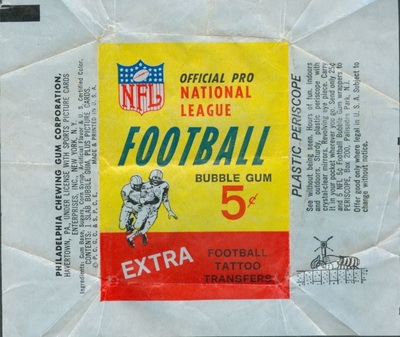

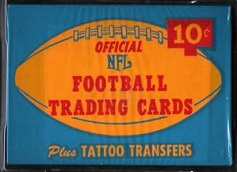

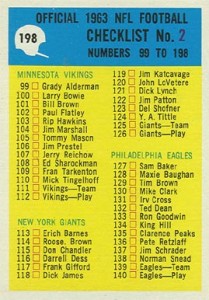

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1964 Philadelphia football set, which had a run of producing NFL cards from 1964 to 1967.

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1964-philadelphia-football-cards-ushered-in-new-era/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed