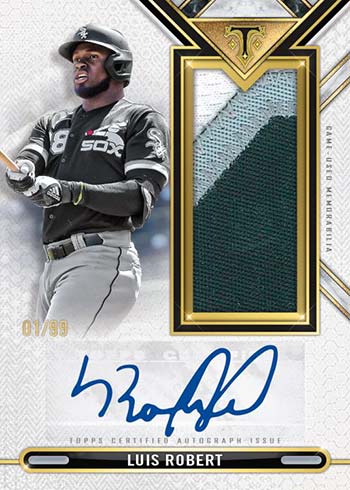

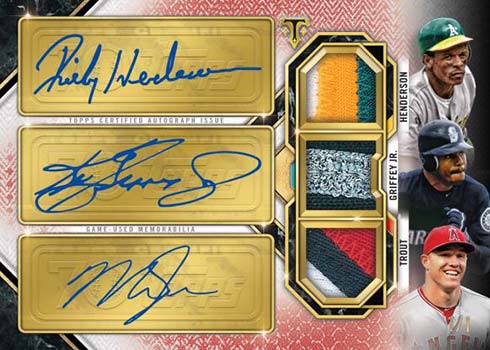

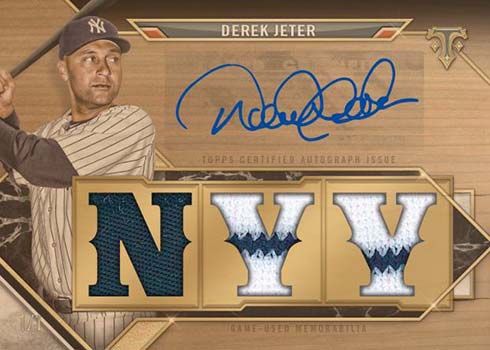

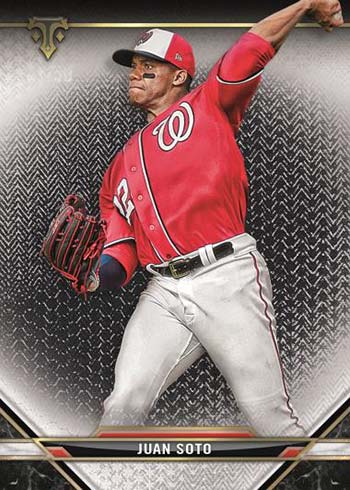

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-triple-threads-follows-familiar-pattern-with-2021-brand/

|

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the release later this year of Topps Triple Threads baseball: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-triple-threads-follows-familiar-pattern-with-2021-brand/

0 Comments

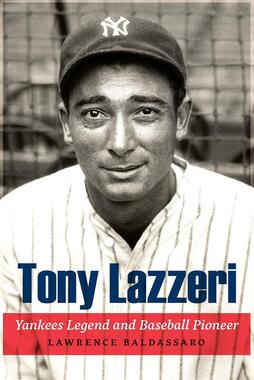

Hall of Famers are normally famous for their achievements. Tony Lazzeri had a stellar 14-year career, played on six American League pennant winners and five World Series champions. He drove in 100 or more runs seven times, had a career .292 batting average, and had double-digit numbers in home runs in 10 seasons despite batting in the lower third of the order. And yet, for many years, Lazzeri was noted for his biggest failure — striking out in a key situation during Game 7 of the 1926 World Series. Grover Cleveland Alexander, who struck out Lazzeri that day, has a notation on his Hall of Fame plaque from 1938 that states the pitcher “won 1926 World Championship for Cardinals by striking out Lazzeri with bases full in final crisis at Yankee Stadium.” As Lawrence Baldassaro writes in his incisive biography about the Yankees’ second baseman, Lazzeri was “relegated to the dustbin of baseball history.” Not anymore. In Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer (University of Nebraska Press; $34.95; hardback; 314 pages), Baldassaro highlights the career of a player who was overlooked but played a key role as a baseball pioneer. A decade before Joe DiMaggio broke into the game, Lazzeri was the first truly big Italian American baseball star. Sure, there was Ping Bodie (born Francesco Stefano Pezzolo), who played from 1911 to 1921, but Richard Ben Cramer described Bodie as “slow of everything but mouth.” In the National League, Babe Pinelli played in the National League from 1922 to 1927 but would have more lasting fame as a major league umpire. Baldassaro provides a deeply researched chronicle of Lazzeri’s baseball career, and also shines a light onto Lazzeri’s personal life, including his battle with epilepsy. The most interesting revelations in Tony Lazzeri are the blatant ethnic slurs he endured — a lot of it coming from sportswriters who believed they were adding colorful adjectives to a story. But, be honest — what player of Italian heritage would want to be known as the “Walloping Wop,” as one writer wrote in an otherwise glowing description. Baldassaro is a professor emeritus of Italian at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. He has written Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball (2011); Baseball Italian Style: Great Stories Told by Italian American Major Leaguers from Crosetti to Piazza (2018); and The Ted Williams Reader in 1991. A native of Chicopee, Massachusetts, Baldassaro watched his first major league game in 1954, when he attended an exhibition game between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Giants. Although a pitcher as a youth, Baldassaro notes that a favorite glove bought for him by his father was a Yogi Berra catcher’s mitt. In Tony Lazzeri, Baldassaro provides a nuanced view of Italian Americans — on and off the baseball diamond. Some of those sportswriters’ descriptions may have been rooted in how Americans perceived Italian immigrants during the first three decades of the 20th century. This is the most fascinating part of Baldassaro’s narrative. Mistrust had been fueled for decades, Baldassaro writes, with even The New York Times depicting Italian immigrants as prone to crime and violence. In 1926, Lazzeri’s rookie season with the Yankees, the most public figures of Italian descent were gangster Al Capone and anarchists Niccolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Baldassaro notes. Lazzeri was overshadowed during his career by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and DiMaggio, but “Poosh-Em-Up Tony” was a steady force on those Yankees’ pennant winners. He was not a nationwide sensation like Ruth — even though he became the first professional baseball player to hit 60 home runs in a season (in 197 games with Salt Lake City during 1925) — but Lazzeri was popular with the Italian populations of every stop in the American League.

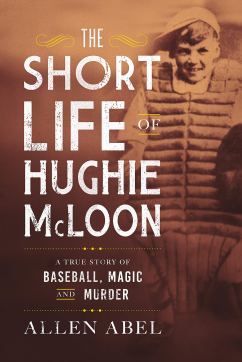

In Luckiest Man, Jonathan Eig described Lazzeri as “a tall, skinny kid, with big ears, a prominent nose, and cheekbones that looked as if they might poke through his flesh.” Baldassaro adds the impressions of sportswriters of the 1920s, who described Lazzeri as “swarthy,” “olive-skinned,” with high cheekbones and “smoldering eyes.” Lazzeri was accepted as a baseball player, but many writers could not exist stirring their stories with strong ethnic undertones, reminding readers that “he was not quite one of us.” “He remained, essentially, equal but separate, sometimes on the fringes of mainstream American culture,” Baldassaro writes. Dialect headlines describing Lazzeri’s baseball ability began in The Salt Lake Tribune in 1925, intended as terms of endearment but laughable and insulting today. After hitting his 58th home run that year, Baldassaro writes, the Tribune headline read, “Our Tone, She Poosh Um Oop Two Time, Maka da Feefty-eight.” Other than the ethnic angle, Lazzeri usually received just passing mention by authors writing about the Yankees of the 1920s and ’30s. Paul Gallico wrote in 1942’s Lou Gehrig: Pride of the “Yankees” that Lazzeri “was no slouch with his funny sliding swing that could park a ball into the bleachers.” Charlie Gentile noted in 2014’s The 1928 New York Yankees that Lazzeri was “considered by many” to be the best second baseman in baseball and worth “at least $150,000” to other teams. Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz quoted Miller Huggins praising Lazzeri in their 2015 work, The Colonel and Hug. The Yankees manager declared that players like Lazzeri “come around once in a generation” and called him “a dead game guy and a terrific competitor.” Baldassaro notes that while Lazzeri’s work on the field was public, there was plenty of mystery about his private life. Even something as innocuous as Lazzeri’s middle name was open for debate. It could have been Michael, Marco or even Mark. Baseball-Reference.com lists it as Michael, and so does the Society for American Baseball Research. However, Lazzeri’s father filed an affidavit to Canadian authorities when Lazzeri was about to take a job managing the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1940, Baldassaro writes, and the middle name was listed as “Marco.” Other legal documents also support Marco or Mark, but even Lazzeri’s descendants are unsure. Other fuzzy details Baldassaro attempts to sharpen include where Lazzeri grew up in San Francisco, and his marriage to Maye Janes — when Lazzeri proposed, he told Maye that he would not leave to play ball in Peoria unless she accompanied him. “I wasn’t sure he loved me, but I knew Tony loved baseball,” Maye Lazzeri said in a 1989 interview. I couldn’t believe he was ready to give up baseball for me.” Later, Baldassaro explores the time Lazzeri filed for divorce in December 1936 on the grounds of cruelty. A day later, the couple reconciled, and there was no mention of it again. “It’s as if this brief drama … immediately disappeared into a black hole, leaving behind no evidence of the issues that led Lazzeri to seek a divorce,” Baldassaro writes. Baldassaro also visits Lazzeri’s contract squabbles with the Yankees. He had a minor tiff with general manager Edward Barrow in 1930 but came to terms quickly. After Lazzeri had a dismal season in 1931, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert speculated that his player was distracted by heavy losses in the stock market. Baldassaro disputes that notion, noting that Lazzeri and his wife bought a six-room house in 1932. If they had lost so much money, “would they have been able to recoup enough of their losses in the height of the Depression to enable them to make such a purchase?” he writes. The author speculates that injury — or perhaps increased episodes with epilepsy — might have been the cause for Lazzeri’s struggles. If Lazzeri’s medication dosage was increased during that time, for example, his reflexes could have been impacted. While Baldassaro is unable to prove the epilepsy theory, it is certainly plausible. Lazzeri’s health issues led to trade rumors during the early 1930s, but the Yankees never made the deal. Good thing, too. Lazzeri’s greatest game came in May 1936, when, batting eighth, he hit a pair of grand slams, a solo homer and a triple and drove in 11 runs. The day before, Lazzeri hit three homers during a doubleheader. His six home runs in three consecutive games set a major league record that stood until 2002, when Shawn Green had seven, Baldassaro writes. Baldassaro’s research is excellent. His bibliography includes 68 books, articles and papers, and there are 19 pages of end notes that reference newspaper articles, census records and scrapbooks from the Lazzeri family. The only major glitches came when Baldassaro mistakenly mixed up Lefty Gomez with Lefty Grove (page 182), and calling the St. Petersburg Times the Tampa Bay Times (a title they did not adopt until 2012) in a 1934 article (also page 182). Those are minor blemishes. The biggest blemish on Lazzeri’s career — the strikeout against Alexander in 1926 — was washed away when he was elected to the Hall of Fame. Tony Lazzeri helps the reader get beneath the surface of those great Yankees teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Lazzeri was a driving force on offense, played strong defense and provided leadership and other intangibles that were crucial to the team’s success. Baldassaro also weaves in the ethnic attitudes of the day, asserting that while Lazzeri was not the first Italian American baseball player, his success helped open the door for others. Baldassaro’s work cuts across baseball, history and social channels, and is an enriching read. Here is a review I wrote for Sport In American History, The Short Life of Hughie McLoon:

ussporthistory.com/2021/04/24/review-the-short-life-of-hughie-mcloon/

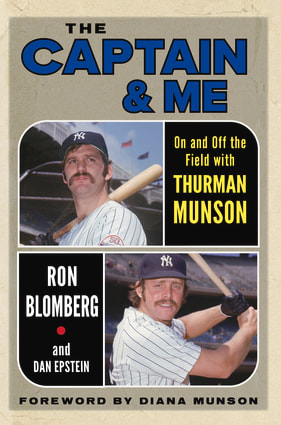

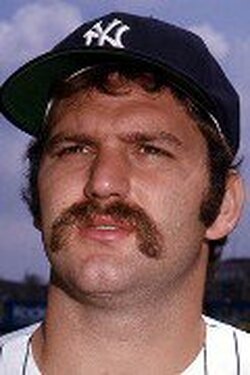

At first glance, Thurman Munson did not look like a “traditional” member of the New York Yankees. He was grumpy, abrasive and not afraid to get down and dirty. His 1971 APBA baseball game card listed his nickname as “Squatty.” But let’s be frank: In the 1970s, Munson was the perfect Yankee: Gritty, tough, intense and focused on winning. He played hurt, and he played well.

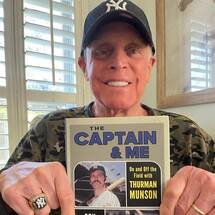

If you rooted for the Yankees during that time — it’s been called the “Horace Clarke era” because the second baseman, fairly or unfairly, epitomized the dog days of baseball in the Bronx — Munson was the working class guy you wanted to lead your team. I was a teenager during the early part of the 1970s and a Yankees fan, so I was not spoiled by the dominance New York enjoyed between 1921 and 1964 — 29 pennants, 20 World Series titles — so even getting close to the playoffs was a big deal. But we know the facts: Munson was a seven-time All-Star and the American League’s Most Valuable player in 1976. But Munson’s shocking and untimely death in an Aug. 2, 1979, plane crash as he was practicing takeoffs and landings at an airport near his home in Canton, Ohio, cut short what should have been a Hall of Fame career. We don’t know what Munson was like away from the field, but former Yankees player and teammate Ron Blomberg, along with author Dan Epstein, provide some much-needed perspective about the Yankees team captain. The Captain & Me: On and Off the Field with Thurman Munson (Triumph Books; $28; hardback; 284 pages) is a warm, funny, sentimental and honest look at a player who was misunderstood and underappreciated by many baseball fans outside of New York. The cover of the book is a clever adaptation of a 1970 Topps baseball rookie card, the year Munson won the American League Rookie of the Year award. The book’s title comes from a 1973 album of the same name by the Doobie Brothers, a favorite group of Munson’s and the year Blomberg made history in Boston by becoming major league baseball’s first designated hitter.  Ron Blomberg Ron Blomberg

Epstein properly notes that The Captain & Me is not a straight biography of Munson. That’s been done before, most notably and thoroughly in 2009’s Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain by Marty Appel. And Blomberg covered his own career in his 2012 autobiography, Designated Hebrew.

This book is more like a conversation with Blomberg at the old Stage Deli in Manhattan, which had a sandwich named for him – a triple-decker combination of corned beef, pastrami and chopped liver, topped with a Bermuda onion (“I always thought chopped liver was disgusting, so I could never actually eat it,” he writes). Blomberg’s eating exploits may have been more prodigious than his sweet left-handed swing that was tailor-made for old Yankee Stadium’s 296-foot porch in right field. nterestingly enough, Blomberg hit 34 home runs from 1969 to 1973 at the original Yankee Stadium. Blomberg hit 17 at home and 16 on the road. Blomberg, 72, opens The Captain & Me with a food anecdote on the day he debuted as a DH. Blomberg was devouring deviled eggs at a rapid clip in the clubhouse, and Munson was not pleased. The two were first-round draft choices of the Yankees — Blomberg was the No. 1 overall pick in 1967, and Munson was No. 4 overall in 1968. Blomberg could see right away that Munson was all-business about baseball. “Once he was on the field, he was deadly serious about playing and winning,” Blomberg writes.  Thurman Munson Thurman Munson

The pair became friends in September 1969 and shared their experiences through the years. Blomberg introduced Munson to matzo ball soup and got him hooked on pastrami and corned beef on rye, instead of than White Castle burgers. Munson was a devoted family man, and Blomberg was able to see his softer side.

“Tough and gruff as he seemed on the surface, he was really over the moon about becoming a dad,” Blomberg writes. “It was like he would visibly soften into a giant teddy bear whenever the subject came up.” Blomberg, meanwhile, peppers the reader with baseball anecdotes, and his legendary eating habits are usually part of the stew. By hitting the buffet too many times at the Chateau Madrid in Fort Lauderdale during spring training, Blomberg caused the team to be banned from the restaurant. Teammates were upset at management, but “they were really upset at me for ruining such a good dining situation,” he writes. Epstein’s job in The Captain & Me is to provide historical context and a timeline, and he does it well. He is uniquely positioned to write about 1970s baseball, with two excellent books to his credit — Big Hair and Plastic Grass: Baseball and America in the Swinging ’70s in 2010, and Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Season of 1976 in 2014. Epstein breaks up Blomberg’s narrative with good information and statistics.

Blomberg, meanwhile, explores his good relationship with Munson — as opposed to the catcher’s battles with the media.

Munson “had no patience with doing interviews, and no trust in most of the writers,” Blomberg writes. “When you are in the clubhouse, this is my house,” Munson once explained to Blomberg. “I do what I want to do, and I talk to who I want to talk to. And if I want to get in someone’s face, I get in someone’s face.” As a sportswriter, I’ve been on the receiving end of that. Telling an athlete that while the clubhouse may be his home, it is my office, does not get a warm reaction. But Munson was generous with young pitchers and knew how to call a game. If pitchers trusted him, invariably they would become more effective. He was a quiet prankster, too, and loved to fish and play golf. Munson also had a soft spot for children with medical issues or veterans and would take the time to autograph baseballs and chat with them, Blomberg writes. Munson and Blomberg would often make unannounced and unpublicized visits to children’s hospitals. “You should have seen how great Thurman was with these kids,” Blomberg writes. “His whole attitude would change, because he loved to see kids laughing and playing, and he would whatever he could to get them to smile.” Blomberg admits that the public and the media never saw that side of Munson, noting that “the writers probably wouldn’t have even recognized the guy he was around those kids.” Blomberg also writes about Munson’s trickery on the field and how he was able to scuff baseballs without the home plate umpires catching him in the act. Or how he would spit to signal the first baseman that a snap throw was coming. Blomberg also reveals how Munson would slip him a “greenie” — an amphetamine that was “really like a No Doz” — “just something to wake you up.” “All of a sudden I felt like I was in ‘The Jetsons!’ Blomberg writes. “I felt great and ready to play. But when I got up to the plate, I was so hyper my hands were shaking, and the ball looked like three balls coming at me.” That was a one-off for Blomberg, who points out that Munson did not take drugs and was more of a “natural high guy.” Blomberg’s stories about record producer Nat Tarnopol are interesting, and the relationship was “like a fantasy for me and Thurman.” As president of Brunswick Records, Tarnopol oversaw 19 top-10 hits on the Billboard charts between 1970 and 1975. He would introduce Blomberg and Munson to some “heavy hitters” in the business world — and the underworld, too. “I was really naïve about these guys, to be honest; I didn’t realize until years later that they were gangsters,” Blomberg writes. “But they were big-hearted guys who treated Thurman and I like we were their long-lost brothers, and they’d do anything for us.” Tarnopol bought cars for both players, and they never had to wait for a table or buy a meal when they were his guests. The record executive even considered buying the Yankees from CBS, but the network would not sell to him, Blomberg writes. Blomberg and Munson also mingled with singers like Frankie Valli, Tommy James and Jay Black.

What is also interesting in The Captain & Me is Blomberg’s insight into the rivalry between Munson and his Boston catching rival, Carlton Fisk. The two rumbled after a memorable collision at the plate during the ninth inning of a 2-2 game at Fenway Park on Aug. 1, 1973. Both catchers were ejected, but the die was cast. There was no love lost between them. “I think that had Thurman lived, he would still hate Fisk today,” Blomberg writes. “And if Fisk died tomorrow, him and Thurman would have a fight up in heaven.” Left unsaid, but probably true, is that Munson probably would have done a slow burn after Fisk was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2000. Blomberg believes Munson belongs in Cooperstown, but the catcher never received more than 15.5% during the 15 years he was eligible in for election by tenured members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. He did not fare well in later voting by the Veterans Committee.

For those who want to see the pros and cons about putting Munson in the Hall, a 2019 article by Chris Haft of MLB.com is required reading.

Put Blomberg in the “pros” category. “In my view, his skills, his accomplishments, his leadership, and what he did for baseball” qualify him for enshrinement, Blomberg writes. That remains to be seen. As memories dim, so do achievements. Munson had plenty of intangibles that made him great, but number crunchers may not be impressed by his career marks. Munson led the Yankees to three consecutive World Series (1976-1978) and had the wild-card format been around during the 1970s, New York would have made the postseason in 1970 and 1974. The Captain & Me is a wonderful tribute and is full of stories — funny, touching and sad. Injuries shortened Blomberg’s career, and he left New York and finished his career with the Chicago White Sox in 1978. There are great stories about Reggie Jackson, Billy Martin, George Steinbrenner, Sam McDowell and Mickey Rivers. And even a few about Horace Clarke. As it turns out, that era wasn’t so bad after all. Here is a podcast I did on the New Books Network with Bruce Berglund, author of The Fastest Game in the World.

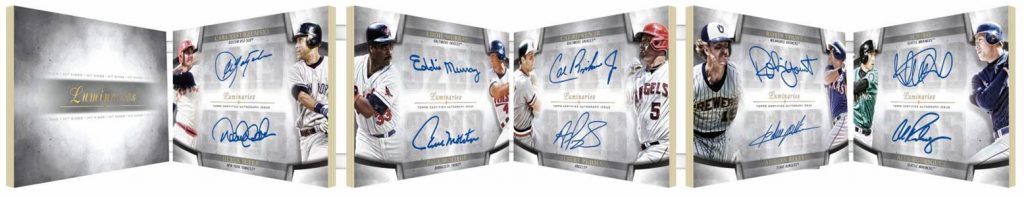

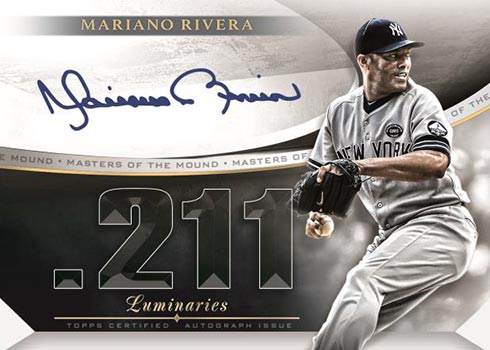

newbooksnetwork.com/the-fastest-game-in-the-world Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about 2021 Topps Luminaries, a very high-end product that is coming out in August:

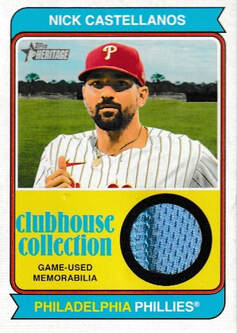

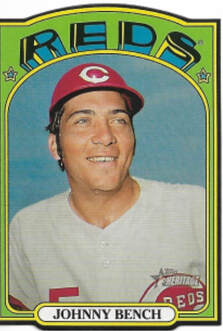

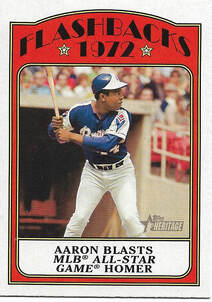

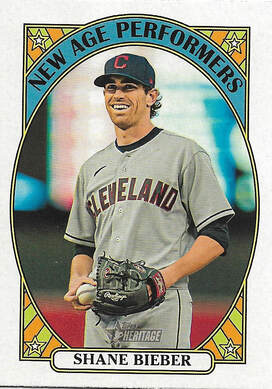

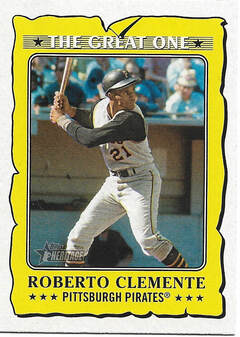

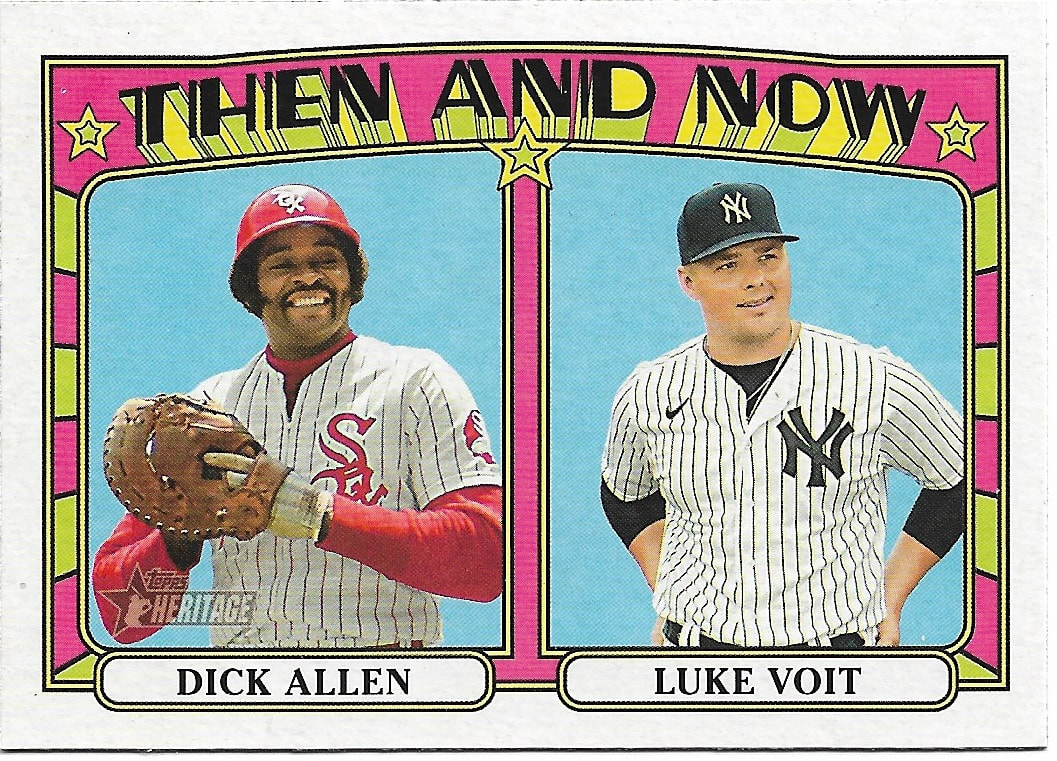

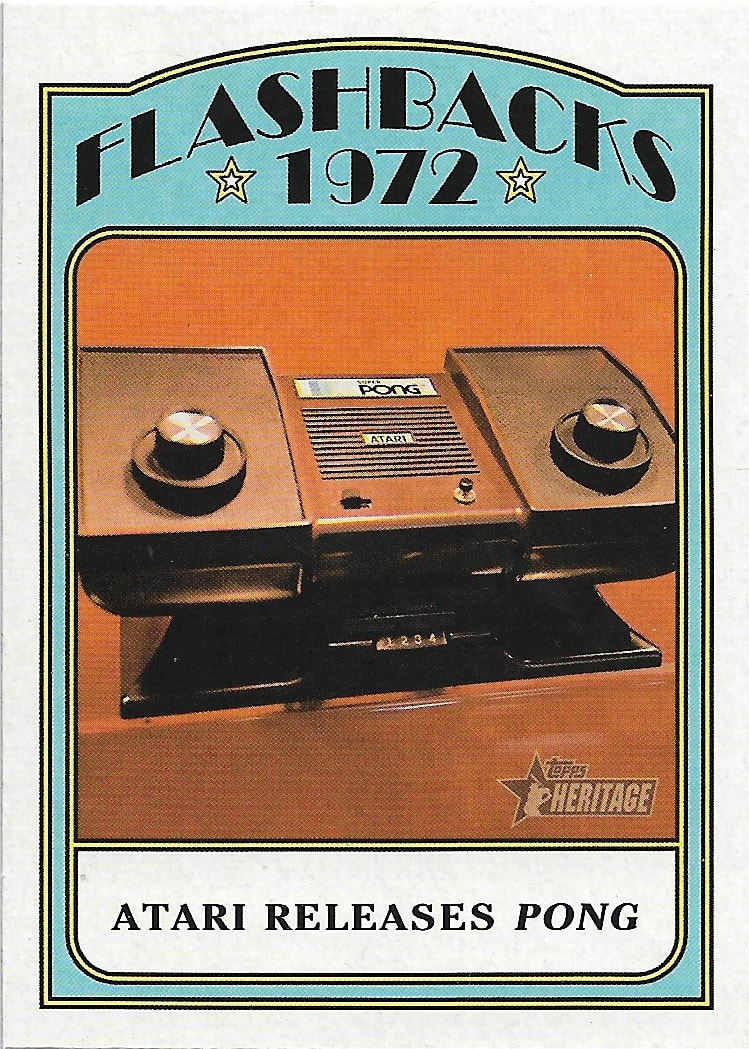

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-luminaries-offers-autographs-galore-including-70-on-one-book-card/  Hands down, the 1972 Topps baseball set was the coolest group of baseball cards during the 1970s. The cards had that psychedelic look with bold team names, occasional action shots and throwbacks like Boyhood Photos of the Stars. The “In Action” cards also had a nice baseball brain teaser, “So You’re a Baseball Expert,” which tested your knowledge about the rules of the game. Now, trying to get a box of Topps 2021 Heritage, which pays tribute to that 1972 set, can be a bit of a challenge unless you want to buy the cards online. As a traditionalist, I enjoy going to stores and buying blaster boxes and packs. Tradition is going out the window. I went to my local Target store Friday morning, shortly after 8 a.m., since the sign where the cards would normally be advised customers that the products would be only available at that time on a come-first basis. Customers would be allowed to buy three items from any set. I get to the store and check in and found that I was No. 24 on the virtual list (Say Hey, Willie Mays would have been proud). The Target guys took my phone number and promised a text when it was my turn. I wondered if there would be any product left. When I walked in, some guy had a shopping cart and was loading it with baseball cards, basketball cards and even Pokémon cards. Goodness.  So I did some shopping while I waited. Came back a few minutes later and checked to see if there were any nine-pocket sleeves. None to be had. The associate asks me if I had checked in and I nodded. Told him what I was looking for, and then he said, “Well, you can’t stay around here. You need to get out of here.” Hmm. Good customer service relations, and since I was shopping for other items, I walked away. I don’t envy the Target associates having to deal with a bunch of collectors — and from the looks of it — a bunch of speculators who were going to flip whatever they bought on eBay. So the associates get a pass. That’s because for the most part, they were friendly. After 35 minutes, I got a text notifying me that it was my turn. Normally, I would have bought maybe a blaster or two. But because of the wait, I bought three Target Mega Boxes of 2021 Heritage at $39.99 apiece.  The difference in my case is that I don’t flip product. Oh, as a kid during the mid-1960s I flipped cards against the wall and stunk at it. Anyway, I enjoy the Heritage product, so I was glad there was still some left. On to my review. I was 14 when 1972 Topps cards were released in the spring of ’72. They were magical then, and the 2021 set captures that same excitement. There are 500 cards in a set, with the last 100 cards (Nos. 401 to 500) considered short prints. Interestingly, Topps did not include card No. 216 — Cavan Biggio — in this set, promising that it will be inserted into the Topps Heritage high number set that will be released in November. On Twitter, Topps said a production error caused the omission but did not elaborate. The production of Biggio’s mini parallel and French variation cards were not affected, however. They can be found in the regular Heritage set. The statement is worded beautifully: “It has come to our attention,” Topps begins. Not sure of the reasoning behind the omission, but “production error” is an eyebrow raiser. I must be getting too skeptical in my old age.  This year’s set has plenty of variations — 91 of them. I didn’t find any this time, other than a French variation card of Kolten Wong. Some of the players have as many as four variations, including action, error, reverse team name color swap and missing stars on the card front. The Heritage Mega Box sold at Target contains 17 packs, with nine cards to a pack. I pulled 289 base cards and 17 short prints from all three boxes. The first box had 138 base cards and seven SPs, which was nice. The other two boxes had five short prints each, which is an average amount. The second box trimmed 115 base cards and five SPs. There were 26 doubles. By the third box — and this was expected — the duplicates far outnumbered the base. I had 35 base cards, five short prints and 105 doubles. That’s OK; the dupes will find homes. The Target Mega Boxes had red border parallels, and I pulled three from each. I also had a red border chrome card of Paul Goldschmidt. Speaking of chrome cards, I found two among the packs I opened. One was of Mike Yastrzemski, numbered to 572. The other featured Mike Trout and was numbered to 999.  Other parallels included mini cards, also set in the 1972 design. I found seven minis, and some of them were goodies — Harmon Killebrew and Johnny Bench from the past, and Bryce Harper, Ronald Acuna Jr., Nolan Arenado, Anthony Rizzo and Casey Mize from the present. The Mega Boxes did not yield a large number of inserts, but there was a good representation. Heritage collectors are familiar with Then and Now and New Age Performer cards. The boxes I opened had Then and Now cards of Hank Aaron and Marcell Ozuna, Dick Allen and Luke Voit, and Gaylord Perry and Shane Bieber. Each box contained a New Age Performer card, so I pulled Bieber, Brandon Lowe and Jo Adell. Paying tribute to current events and sports from 49 years ago, the Flashbacks 1972 cards I pulled were “Atari Releases Pong” (does anyone recall how that seemed so innovative at the time?), the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and Aaron hitting a home run in the All-Star Game. In a nice tribute, The Great One honors the career of Hall of Fame outfielder Roberto Clemente. Fittingly, the subset has 21 cards, matching his uniform number. Clemente was an iconic player and a humanitarian, and his charitable deeds cost him his life. On Dec. 31, 1972, he died in a plane crash shortly after takeoff from Puerto Rico while helping deliver relief to earthquake-ravaged Managua, the capital of Nicaragua. Topps Heritage is always worth the wait. Even if one has to “stand” in a virtual line. It’s filled with nostalgia, and Topps stays true to the design. And the 1972 Topps set had few peers in terms of design. Oh, 1975 comes close, but there was something magical about the ’72 set. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Mile High Card Company's latest auction:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/jordan-mays-rookies-vintage-unopened-top-5-6-million-mile-high-auction/  Tom Petty sang it: “Even the losers keep a little bit of pride.” Nobody really remembers second place. That quote and its variants have been uttered by Walter Hagen, Bobby Unser, “Peanuts” creator Charles M. Schulz and even John Cena. But the 1986 Boston Red Sox lost an epic World Series and are still remembered for coming one pitch away from winning it all. And while they lost, that squad from Boston kept its pride. The team went from the brink of elimination in the American League Championship Series to winning the pennant and going seven games in the World Series. In a two-week span, the Red Sox experienced ecstasy and agony. But life goes on, and there is more to life than losing. And that is what Erik Sherman captures so well in his latest book, Two Sides of Glory: The 1986 Boston Red Sox in Their Own Words (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 253 pages). Sherman has written about the 1986 season before, but from the perspective of the New York Mets. He wrote 2016’s Kings of Queens: Life Beyond Baseball with the ’86 Mets, and co-wrote Mookie: Life, Baseball, and the ’86 Mets with Mookie Wilson. He also collaborated with Davey Johnson for the former Mets’ manager’s 2018 autobiography, Davey Johnson: My Wild Ride in Baseball and Beyond. Sherman co-wrote another warm book of recollections, After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the 1969 Mets with former outfielder Art Shamsky. How ironic that a guy who attended Emerson College in Boston had not written about one of the greatest “what if” teams of all time — the 1986 Red Sox — until now. But it is worth the wait. The Red Sox have won four World Series titles in the 21st century, so it is easier to look back. Sherman presents a poignant look at the main players from that 1986 team, writing in a conversational way so readers feel like they are sitting in on the discussion. The Sox lost that best-of-seven series 35 years ago, but the memories remain fresh by the men who lived it. As Sherman writes in his introduction, he wanted to capture “the team’s very soul.” Sherman interviews a wide swath of players, including Bill Buckner, Roger Clemens, Jim Rice, Calvin Schiraldi, Bruce Hurst, Bob Stanley, Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd, Wade Boggs, Dwight Evans and more. Fittingly, Sherman opens the book by interviewing Buckner, the first baseman whose error in Game 6 capped an unlikely rally by the Mets. Buckner’s error did not lose the Series—the game was tied when Wilson hit the slow roller in the 10th inning — but he wore the goat horns and was the symbol of Beantown frustration. Sherman calls his talk with Buckner, who died on May 27, 2019, the player’s last major interview. Buckner speaks about his personal and business relationship with Wilson, as they appeared together for several autograph sessions with fans. And addresses “the Buckner play” head on. “Do I think I lost the World Series? Obviously no. But it wasn’t good,” Buckner tells Sherman. “The only good that came out of it was that I had a lot of people who were inspired by it. I got so many nice letters. People were writing from the heart.”  The range of emotions of the players ranged from Boggs’ enthusiasm to Rich Gedman’s difficulty in speaking about the Series and his time in Boston — “It’s absolutely mind-blowing when you think about it. And gosh, I was a part of that,” Gedman tells Sherman. “It’s really amazing to me. I have to pinch myself. At the time I didn’t realize how big it was.” Jim Rice, who Sherman describes as “easily one of the more challenging interviews in baseball,” doesn’t shy away from that reputation. When Sherman starts off a question with “When you came up with Fred Lynn,” Rice cuts him off. “Let’s clear this up. Lynn came up with me!” Rice says. After navigating that scolding, Sherman gets Rice to open up what turned out to be a fun interview. Boyd, who said he pitched every game in the majors while under the influence of marijuana, offers an enthusiastic interview and one that will make the reader think about social and racial issues. Boyd’s idol was Satchel Paige, and his theatrics on the mound mirrored the great right-hander. And he makes some interesting observations about Jackie Robinson, and what No. 42 might think about the fewer number of Blacks currently in the majors. “You would think that by (Jackie’s crossing the color barrier) it would be grand (for Black players),” Boyd tells Sherman. “But I think Jackie would be sick to know that (Blacks) are not playing now. “So in actuality he didn’t do too much because they’re not playing today.” Boyd adds that he was a fifth-generation professional baseball player. “My people were playing before Jackie was born,” Boyd tells Sherman. Boyd remains angry over not being selected to the 1986 All-Star team and not being tapped to start Game 7 of the ’86 World Series. A rainout after Game 6 allowed manager John McNamara to go with Hurst, who had already beaten the Mets twice in the Series. “Everybody on the team knew I would’ve beaten the Mets,” Boyd says. “I love Bruce. He was a good pitcher. He did well to beat them twice.” But Boyd believed “it was going to be hard as hell to beat them three times.” Hurst broke down three times while Sherman interviewed him. Sherman thought he was going to get a tame chat, especially since he had interviewed the more colorful players. But Sherman’s three-hour interview with Hurst “would quickly turn into one of the most poignant, emotional and reflective meetings I’ve ever had with a ballplayer.” Hurst had not done interviews for nearly three years, but he agreed because “I don’t want to be that guy.” Hurst spoke about battling the perception that he was “soft” and lacked toughness. He recalls Carl Yastrzemski — Hurst grew up with a poster of Yaz over his bed — telling him, “You’re the worst pitcher I’ve seen in twenty years—bar none. You’re the worst!” Even though Hurst was a rookie, he fired back. “The Red Sox should have traded you and kept Reggie Smith!” Beautiful. Had the Red Sox won Game 6, it is likely Hurst would have been named the Series MVP. But the thrill of winning the championship would have been greater. “Can you imagine what it would have been like to jump up and down in that clubhouse?” Hurst asks, full of emotion. Sherman’s other interviews are just as good. Clemens is upbeat and enthusiastic, more than one might expect. Schiraldi leans on his faith and is also pragmatic — “you’re a hero one day, and you’re a goat the next.” The memories Sherman pulls out of the players are meaningful. Sherman has a unique ability to ask pointed questions without being too confrontational or assertive. He approaches these Red Sox players gingerly, and it pays off. In some cases, they told him more than he expected. Hurst is a good example. Stanley, who threw the infamous wild pitch that enabled the Mets to tie Game 6, prefers to look at the big picture, Sherman writes. His son was diagnosed with cancer in his sinus area in 1990. “You can take that ’86 World Series — and my whole career — and throw it out the window,” Stanley says. “I got the health of my son and that’s all that counts for me.” In his epilogue, Sherman mentions the players who did not get the full chapter treatment but still played critical roles for Boston. What shines through in Two Sides of Glory is the 1986 Red Sox players’ love for each other and the game they played. They suffered an agonizing defeat in the World Series, and if they had won it all the team would have been hailed as a great one. That, and ending the Curse of the Bambino — which eventually happened in 2004 in spectacular fashion. Sherman presents the flip side of the 1986 World Series in an engaging, passionate and fascinating narrative. He shows that even though the Red Sox lost in agonizing fashion, they still kept their pride. And in the final analysis, that is what counted most. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed