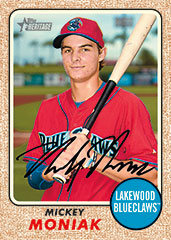

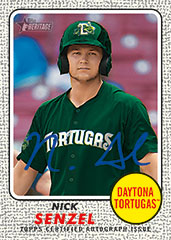

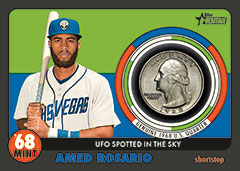

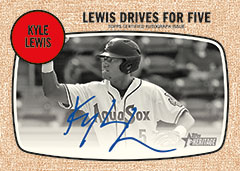

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-topps-heritage-minor-league-preview/

|

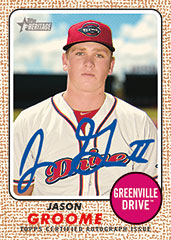

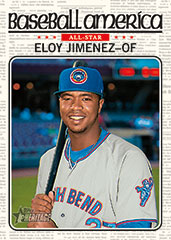

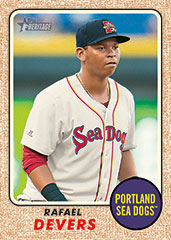

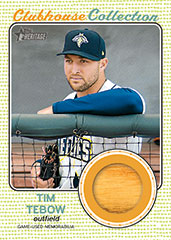

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the September release of Topps' 2017 Heritage Minor League baseball: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-topps-heritage-minor-league-preview/

0 Comments

Here's a story I wrote about the 2017 Bowman High Tek set that will make its debut in August:

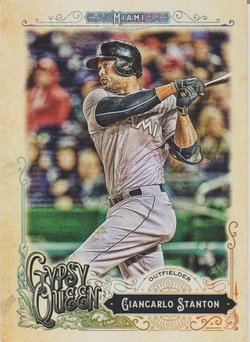

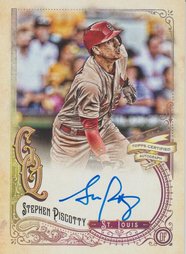

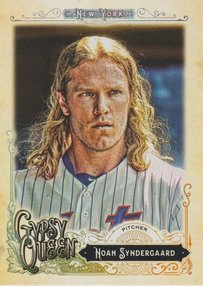

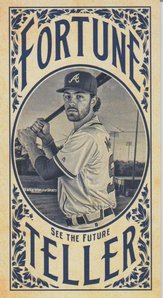

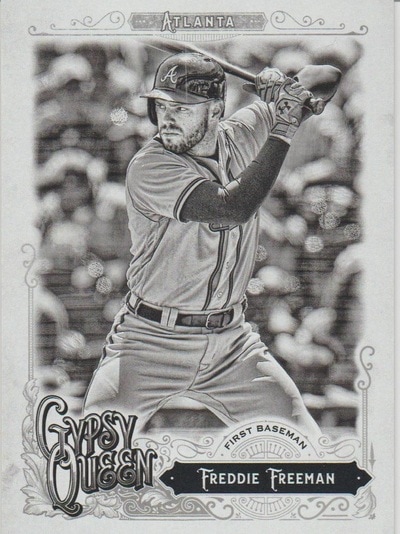

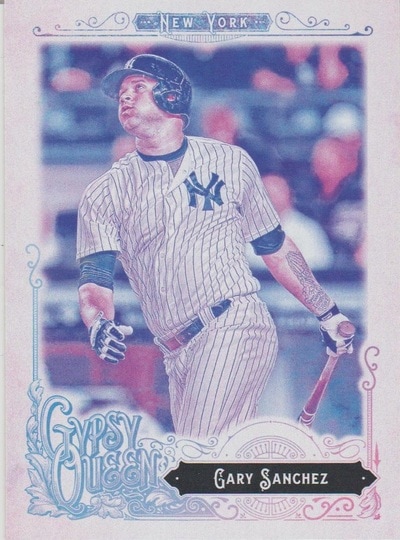

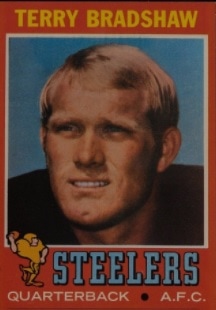

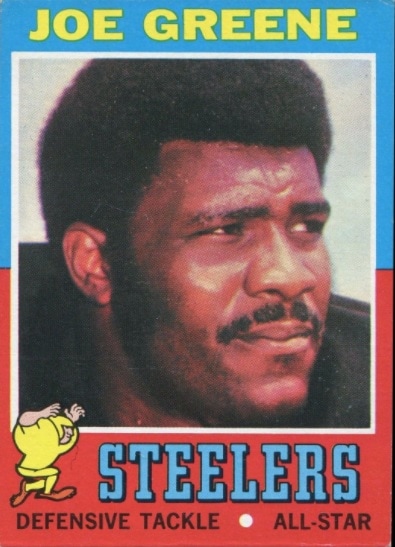

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/bowman-high-tek-will-debut-in-august/  The configuration is different this year, but Topps’ Gypsy Queen remains an intriguing set. There is something charming about cards that sport a painted-on look, and Gypsy Queen has always excelled in that regard. The set is cheaper than last year’s version, ranging in price as low as $59.99 for a 24-pack retail box on one internet site (Fans Edge, which also offers free shipping). However, hobby boxes will fall in the $89 to $115 range, depending on the retailer. A hobby box also will contain 24 packs, with eight cards to a pack. Whereas in previous years there were two autographs and two relics in each hobby box, this year’s version is limited to two on-card autos. The mini-parallels are gone, and so are the paper-framed parallels. However, Topps unveiled a new design and added an oversized chrome box-topper that is absolutely beautiful. The base set for Gypsy Queen is 300 cards that consist of rookies and veterans. There are an additional 20 short-printed retired stars and Hall of Famers. In the hobby box I opened, I pulled 173 base cards and one short print. I had a second short print, but it was a variation — a missing nameplate card of Babe Ruth. The missing nameplate cards will fall one in every nine packs on average.  Other variations include capless players, throwback uniforms and gum logo cards (cards with what looks like a small jar full of Topps gum, listed for a penny apiece, on the card back). I also pulled a pair of purple parallels, numbered to 250. Collectors might find hobby-exclusive black-and-white parallels, numbered to 50 — there was one in the box I sampled — red (numbered to 10) and 1/1 black. For those buying retail, there are green parallels numbered to 99. The capless cards are interesting, as they showcase the hairdos of players. And the one I pulled was a perfect example, with Noah Syndergaard’s flowing locks adorning card No. 198. The design did undergo some distinct changes. In 2016, for example, the player was identified only by his last name and his first initial at the bottom of the card front; in 2017, his full name is featured on a black nameplate that is situated in the bottom right-hand corner of the card.  In 2016, the Gypsy Queen logo was in bold red block letters that dominated the bottom of the card; this year, the logo appears in a different type font and is squeezed to the bottom left of the card front. And while the 2016 image was contained inside distinct lines, the 2017 image sports a more feathered look. For this year’s product, the player’s team city is listed at the top. The card backs this year feature the player’s name in a banner at the top, with his team name above it and his position below it. While five lines of biographical type were used in the 2016 Gypsy Queen set, six are used this year. A drawback to this year’s set is the color of the font that identifies the card number. Instead of simply listing the card number at the top (like in the 2016 version), the ’17 model lists it more formally, like “No. 1 in a series of 320.” It is displayed in all capital letters, but the burnt-orange color of the type face tends to blend into the cream-colored background of the card back. It’s difficult to read; well, at least for an old, longtime collector like me.  Topps promises two autographs per hobby box, and that average was met in the product I opened. The two on-card signatures I received were of Cardinals outfielder Stephen Piscotty and Mets pitcher Robert Gsellman. Some collectors might pull purple, black-and-white, and 1/1 black parallel versions of these autographs. The box-topper is a hobby exclusive called GlassWorks. This is an oversized, 25-card set; I pulled a Clayton Kershaw card. The chrome really makes the card shimmer and shine. There are parallels in purple (numbered to 150), red (25) and black (1/1). There also are nine autograph parallels, numbered to 9. A typical hobby box will yield seven inserts. I pulled three from the Hand Drawn Art insert, which depicts players in a more artistic format than the base cards. There are 38 of these cards. The second insert is a cross between a mini and a regular-sized base card. Called Fortune Teller, these cards are as tall as a base card but only three-quarters as wide. The format is to make a prediction about what a player might do in 2017. For example, the card for Dansby Swanson notes that he will never play a game in Triple-A ball and will hit double figures in homers for the Braves. It will be intriguing to read the predictions again in October. Gypsy Queen has undergone a few changes, but it has not lost its general feel. The card-front design is more ornate, which makes it more attractive. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1971 Topps football set:

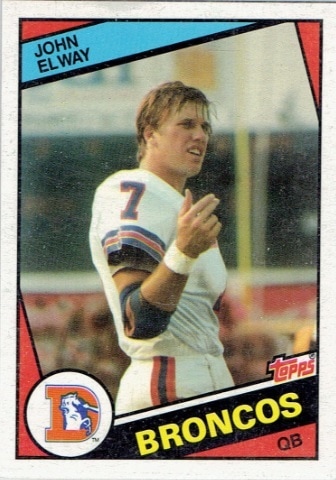

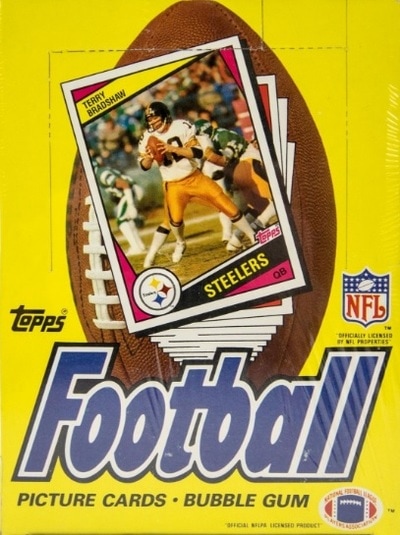

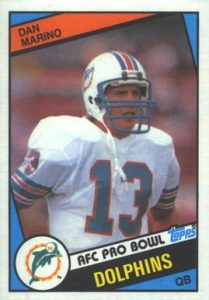

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/73666-2/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1984 Topps football set, which included rookie cards of Dan Marino, John Elway and Eric Dickerson:

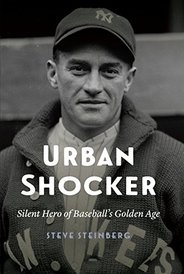

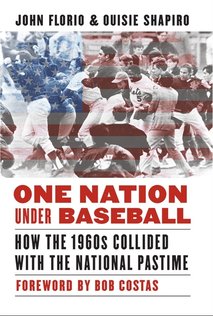

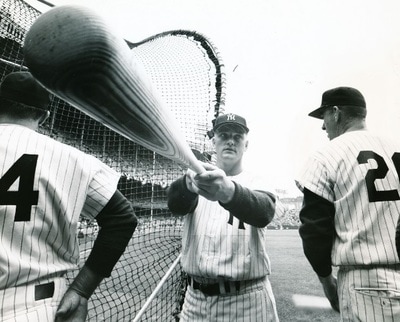

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/73663-2/  The 1920s were a coming of age for major-league baseball. The deadball era had ended, and the lure of the home run, stoked by the power of Babe Ruth, took baseball fans by storm. It showcased the emergence of the New York Yankees as a baseball dynasty, and was witness to the New York Giants’ dominance in the National League from 1921 to 1924. There is so much rich material to be mined from this decade, apart from the obvious themes that dominated the decade. And that’s where Steve Steinberg shines, as he prospects for gold and uncovers a gem of a baseball career that was tragically cut short. In Urban Shocker: Silent Hero of Baseball’s Golden Age (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $32.95; 329 pages), Steinberg chronicles the career of Shocker, an underrated but respected pitcher who played twice for the New York Yankees (1916-1917, 1925-1928) and seven seasons for the St. Louis Browns (1918-1924). Steinberg is no stranger to 1920s baseball, particularly with the history of the Yankees. He has collaborated with Lyle Spatz on two books: 1921: The Yankees, the Giants and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in 2010; and The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees in 2013. Shocker was part of the famous 1927 Yankees team that swept to the pennant and a four-game sweep in the World Series, but his achievements seem to have been buried among the glory carved out by a team that boasted four Hall of Famers in the starting lineup (Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earle Combs and Tony Lazzeri), two in the starting rotation (Waite Hoyt and Herb Pennock) and one calling the shots from the dugout (manager Miller Huggins). A four-time 20-game winner in St. Louis — including an American League-leading 27 in 1921— Shocker won 19 games in 1926 and 18 in ’27 in his second stint in New York. He was one of the pitchers allowed to continue throwing the spitball after it was banned after the 1920 season, and while it was not his money pitch, he was crafty enough to keep batters guessing when he might throw the loaded ball. Before dying from a heart valve that degenerated and pneumonia, Shocker won 187 games in 13 seasons and never had a losing record in the majors. “Shocker is a living example of that thing known as ‘cunning’ in pitching form,” Steinberg quotes sportswriter (and future baseball commissioner) Ford Frick from a 1925 article. The subhead to Steinberg’s book is almost misleading, since for most of his career, Shocker was anything but quiet. He was a fierce competitor who was not afraid to squawk at umpires and opposing players, and he also had a penchant for enjoying the night life during the era of Prohibition. “He enjoys a scrap almost as much as Jack Dempsey,” Steinberg quotes St. Louis sportswriter Harry Pierce. Steinberg became interested in Shocker in 1998 when he found an old baseball card of the pitcher at a card show. Steinberg had recently sold his retail company and decided to research the elusive right-hander. By 2002 he had written more than 200,000 words but shelved the project for seven years. In 2009, Steinberg returned to his Shocker manuscript and began to shape it into a readable biography. The hiatus worked wonders, as Shocker comes to life in this book. Steinberg’s research includes photos from Shocker’s relatives and also from his own personal collection. He also delves into many Canadian newspaper sources to document Shocker’s minor-league career. Steinberg leads off several of his chapters with the verse of legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice, which ties into that chapter’s subject matter rather well. Steinberg also brings out the showman and downright cockiness Shocker displayed when he pitched for the Browns. He “loved the noisy fans” in an opponent’s ballpark and felt energized by their scorn. In 1920 he pulled off a nifty piece of gamesmanship against Ruth in a July 13 game. Shocker struck out 14 batters, and Ruth whiffed three times. It was the second strikeout that raised eyebrows. When Ruth came to bat, Shocker waved his outfielders in. Spoiling Ruth’s timing with a slow pitch for strike one, he beckoned his outfielders to move in even closer. After Ruth swung and missed for strike two, Shocker brought his outfielders to the back fringe of the infield. After setting up Ruth with a fastball outside the strike zone, Shocker came back with a slow pitch that the baffled Bambino missed for strike three. It was part of Shocker’s crusade to let Huggins know that he made a mistake trading him to St. Louis in 1918. Indeed, Shocker was eager to pitch against his old teammates, and while he only went 22-25 against them in 53 starts, he still gave the Yankees fits. Steinberg speculates about how Shocker might have fared had his peak years been with the Yankees and not the Browns. New York finished third in 1920 and then won three straight pennants from 1921 to 1923. Shocker went 91-51 during those seasons in St. Louis, including a 27-12 mark in 1921. From 1920 to 1924, the Browns finished fourth, third, second and fifth in the American League. It’s an intriguing thought, particularly in 1920 and 1924; several well-placed Shocker victories could have resulted in five straight pennants for the Yankees. There are some marvelous nuggets of information culled from the sportswriters of the day, and Steinberg uses them to great effect. Here’s a colorful, descriptive quote from The Sporting News: “Shocker is a trifle temperamental — headstrong, it might more aptly be called. Like all stars, he wants his way. A Bolshevik? Well, no, it’s not that bad.” By the end of 1927, Shocker’s physical condition was worsening. In June 1928, shortness of breath and bouts of dizziness caused him to collapse; the Yankees released him on July 4, since “illness had stepped in where age had failed,” in the words of sportswriter Fred Leib. Shocker would be dead two months later. It was time, Steinberg writes, to tell Shocker’s story. “He’s been waiting for almost ninety years,” he writes. It was worth the wait. Steinberg presents a fascinating portrait of a pitcher who was respected by his peers but faded into obscurity. This new biography brings the pitcher — and the man — back to life.  Politically, socially and economically, our current era is turbulent. Divisiveness is rampant, and so is bitterness. For Americans older than 55, it might seem like the 1960s all over again. That was a time of political awakening, excitement, tragedy and polarization. The baby boomer generation was coming to maturity, and it was not content to just let things continue as they had in the staid, placid 1950s of their parents. It was a time of change. I still believe that in my lifetime, 1968 was one of the most tumultuous years in United States history. Donald Trump lovers and bashers cannot hold a candle to what happened that year — or during the entire decade of the 1960s, for that matter. Major league baseball felt the effects of these seismic changes in American culture, too. And in One Nation Under Baseball: How the 1960s Collided With the National Pastime, (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 222 pages), authors John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro provide a readable, fast-paced primer of the 1960s. Baseball is the backdrop, and there are plenty of stories about the national pastime. But the authors expand their scope to include subjects like Muhammad Ali, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Beatles, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War and racial unrest in the country’s urban areas. Other sports mentioned include boxing and the Olympics. This book is more radical than most in its approach, at least from a formal standpoint. There is no table of contents and no index. The authors note at the outset that their work relies on first-person interviews and archival materials. When quoting from the 59 interviews they conducted, the authors omit attribution. They add that when using secondary sources like books and newspaper accounts, “we’ve provided attribution within the narrative.” It’s almost a 1960s-like “up yours” to the publishing business, radical but fresh. Still, there is a substantial bibliography that has a wonderful cross-section of opinion. It is not skewed toward liberal or conservative thought, but provides an excellent balance. The book opens with pitcher Jim “Mudcat” Grant receiving an invitation to have breakfast with presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in Detroit during the 1960 campaign. It continues with Jackie Robinson’s perceptions of Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon, and a sit-in at Rich’s Department Store in Atlanta that included King. It continues through the decade, addressing many of the social issues that also confronted baseball — segregated living facilities during spring training, which was prevalent in Florida cities. Contract disputes, the locker-room writings of pitchers Jim Brosnan (The Long Season) and Jim Bouton (Ball Four), and the double holdout of Dodgers teammates Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. But it all came back to racial tensions and hatred. “America was coming to grips with a new wave of hatred,” the authors write. Florio and Shapiro discuss the race riots in Philadelphia in late August 1964 and the Phillies’ subsequent collapse, and the 1965 fight between Richie Allen and Frank Thomas that assumed ugly racial overtones. There is lots of good baseball that gets mentioned in this book, too. The Tigers’ comeback victory in the 1968 World Series and the New York Mets’ “miracle” the following season are dutifully chronicled. The book ends with Curt Flood’s lawsuit against baseball’s reserve clause and Muhammad Ali having his draft evasion conviction overturned. Florio and Shapiro selected some very interesting stories to tell, and they tell them well. There is not much nuts-and-bolts sportswriting in this work, but the authors’ ability to place baseball in the context of the 1960s makes this a compelling read. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an RMY Auctions that features more than 1,770 photographic items. Roger Maris is one of the featured auctions.

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/maris-photograph-among-more-than-1700-at-rmy-auctions-sale/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1972 Topps football set:

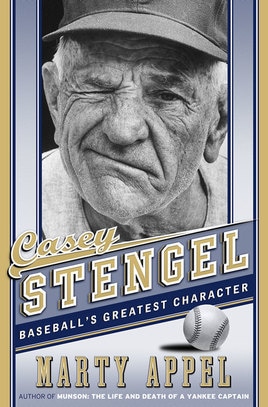

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1972-topps-football-offered-stars-scarce-high-numbers/  I have this vision of a young Marty Appel, working as publicity director for the New York Yankees during the early 1970s, combing through the depths of old Yankee Stadium in search of old treasures. Knowing Appel’s natural curiosity and tenacity, he would uncover some gems. That’s the same vision readers will have while reading Appel’s latest book, Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character (Doubleday; hardback; $27.95; 413 pages). That’s because Appel, who has written extensively about the Yankees — his portfolio includes 2012’s Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees from Before the Babe to After the Boss; and Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain (2009) — has produced an entertaining look at the “Ol’ Perfessor.” He unearths facts about Stengel’s youth, his rough-and-tumble days in the minor leagues, and his eventual rise to the major leagues. And Appel strikes pure gold at every turn. The label of “baseball’s greatest character” was not an arbitrary one, The MLB Network’s Prime 9 show made that determination in 2009, and they had plenty of evidence — Stengel’s ability to mangle the English language (his version was called Stengelese, as a Congressional panel famously discovered in 1958), and his talent for holding court with sportswriters for hours. And those quotes, burned into a baseball fan’s soul: “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them”; “I’ll never make the mistake of being 70 again”; and “If anybody wants me, tell them I’m being embalmed.” And let’s not forget his plaintive cry about the 1962 New York Mets: “Can’t anybody here play this game?” The Mets were awful, but Stengel was able to deflect the attention of fans and sportswriters away from his team’s terrible record because of his personality and colorful persona. He was a marketing genius before the term existed. A definitive biography of Stengel already exists, written by Robert Creamer in 1984 (Stengel: His Life and Times). However, Appel gained access to Edna Lawson Stengel’s unpublished memoirs, which proved to be a valuable resource. Appel also notes that digitized newspapers and access to them via the internet enabled him to find information that was not as readily available when Creamer wrote about Stengel in the 1980s. Appel also tapped into an unpublished memoir of longtime Yankees coach Frank Crosetti and an audio interview with Roger Peckinpaugh. Stengel himself might have called Appel’s researching ability “amazin’.” His bibliography taps a wealth of sources (including Creamer’s book), four of his own books and an unpublished 1963 manuscript that he co-wrote as a teen with Jeffrey Krebs, “Let’s Go Mets.” In addition to his own research, Appel builds his narrative with plenty of help from other sources. His bibliography includes books written by Peter Golenbock, Donald Honig, Fred Lieb, Roger Kahn, Richard Ben Cramer, Jimmy Cannon, Grantland Rice, Jimmy Cannon, Jimmy Breslin and many others. He also cites dozens of newspapers, and not just from New York. Websites are consulted, along with work done by the Society for American Baseball Research. It’s a thorough presentation. Stengel had a modest major-league career, playing with Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, the New York Giants and Boston Braves from 1912 to 1925. He batted .284 during his career and appeared in three World Series, hitting the first postseason home run—an inside-the-park home run — at Yankee Stadium in 1923. But it was the time spent as a manager — particularly his 12 years managing the Yankees — that cemented Stengel’s fame and a plaque at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Stengel won 10 pennants and seven World Series between 1949 and 1960. He came to the Yankees in 1949 after a successful minor-league managing career, but had flopped in the National League with Brooklyn and Boston. He was considered a clown by critics, but Stengel, blessed with talented players for the first time in his managerial career, revolutionized the game. Although he hated being platooned by manager John McGraw when he played for the Giants, Stengel did the same thing with the Yankees, shuffling lineups and plugging in players. He was not afraid to send up a pinch hitter early to break open a game, and sometimes had his pitcher bat eighth in the lineup. He also was not afraid to yank a starting pitcher out of a game when he faltered, even if the game was in its early stages. The moves were unorthodox, but Stengel had a .636 winning percentage with the Yankees, compiling 1,149 regular-season victories. Boston sportswriter Dave Egan, who watched Stengel manage the Braves poorly in the late 1930s and early ’40s, wrote that the Yankees were mathematically eliminated from the 1949 American League pennant race when Stengel was introduced as manager. “Stengel is not a baseball manager at all,” Egan wrote. “He is purely a baseball politician, which explains why he keeps cavorting into good jobs while his betters stand on the outside hungrily looking in.” Stengel would get the last laugh, and as Appel writes, “Egan died in 1958, eight Casey pennants later.” Appel uses Edna Stengel’s memoirs liberally, and it helps make Stengel more human. Sure, he was a winking, grimacing, smiling, wise-cracking manager, but his wife’s observations gave Stengel more depth; he was more than just a manager. It’s certainly true that the 1949 pennant and World Series title changed Stengel’s life. “He had gone from clown to genius ‘overnight,’” Appel writes, “and suddenly he was baseball nobility.” That credibility would not fade even after Stengel took over the Mets and never won more than 53 games in a season. Appel’s research is certainly excellent and thorough, but a few glitches did slip through. For example, he writes in Chapter 18 that the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers went 102-1 in 1944 to win the American Association pennant. Perhaps Appel was thinking of his 2010 book, 162-0: Imagine a Season in Which the Yankees Never Lose. But that was a typo, albeit an eye-opening one. The Brewers actually went 102-51 that season. A more unfortunate one comes in the same chapter, when Appel notes that Cookie Lavagetto was a hero in Brooklyn during the 1947 World Series when he robbed Joe DiMaggio of a home run and broke up Bill Bevens’ no-hitter. Appel is correct about Bevens, but it was Al Gionfriddo that robbed the Yankee Clipper of a homer during that World Series. He also misspells the maiden and married names of Babe Didrikson Zaharias in Chapter 35. These mistakes, however, are peripheral to the actual narrative, so they really do not detract from or damage Appel’s credibility. And while this is a positive look at Stengel, Appel does not hesitate to cite his critics (and there were many), who looked at him not as a genius, but as a manager who was at the right place at the right time. It was the same type of charge leveled at Joe McCarthy, who was called a “push-button” manager near the end of his tenure with the Yankees. McCarthy answered his detractors with eight pennants and seven World Series titles; Stengel would do the same, with 10 pennants and seven World Series rings. Success can silence your critics. I doubt that Appel has many critics. He writes in an easy conversational style, at times throwing in little asides for humorous effect. He writes in Chapter 43 that an aging Stengel, in his final years, cursed at a young Yankees publicist in 1974 when prodded about responding to an invitation to an Old-Timers’ Day game. That publicist was Appel, who became the Yankees’ public relations director in 1973. Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character is a fitting title for a unique figure in baseball history. Marty Appel brings him back to life, giving a new generation of baseball fans a taste of the brilliant, witty, sarcastic and irrepressible figure who dearly loved the game.  Casey's statue adorns the premises at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Casey's statue adorns the premises at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed