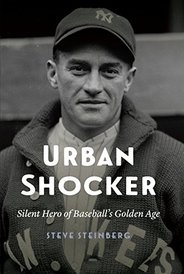

There is so much rich material to be mined from this decade, apart from the obvious themes that dominated the decade. And that’s where Steve Steinberg shines, as he prospects for gold and uncovers a gem of a baseball career that was tragically cut short. In Urban Shocker: Silent Hero of Baseball’s Golden Age (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $32.95; 329 pages), Steinberg chronicles the career of Shocker, an underrated but respected pitcher who played twice for the New York Yankees (1916-1917, 1925-1928) and seven seasons for the St. Louis Browns (1918-1924).

Steinberg is no stranger to 1920s baseball, particularly with the history of the Yankees. He has collaborated with Lyle Spatz on two books: 1921: The Yankees, the Giants and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in 2010; and The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees in 2013.

Shocker was part of the famous 1927 Yankees team that swept to the pennant and a four-game sweep in the World Series, but his achievements seem to have been buried among the glory carved out by a team that boasted four Hall of Famers in the starting lineup (Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earle Combs and Tony Lazzeri), two in the starting rotation (Waite Hoyt and Herb Pennock) and one calling the shots from the dugout (manager Miller Huggins).

A four-time 20-game winner in St. Louis — including an American League-leading 27 in 1921— Shocker won 19 games in 1926 and 18 in ’27 in his second stint in New York. He was one of the pitchers allowed to continue throwing the spitball after it was banned after the 1920 season, and while it was not his money pitch, he was crafty enough to keep batters guessing when he might throw the loaded ball. Before dying from a heart valve that degenerated and pneumonia, Shocker won 187 games in 13 seasons and never had a losing record in the majors.

“Shocker is a living example of that thing known as ‘cunning’ in pitching form,” Steinberg quotes sportswriter (and future baseball commissioner) Ford Frick from a 1925 article.

The subhead to Steinberg’s book is almost misleading, since for most of his career, Shocker was anything but quiet. He was a fierce competitor who was not afraid to squawk at umpires and opposing players, and he also had a penchant for enjoying the night life during the era of Prohibition. “He enjoys a scrap almost as much as Jack Dempsey,” Steinberg quotes St. Louis sportswriter Harry Pierce.

Steinberg became interested in Shocker in 1998 when he found an old baseball card of the pitcher at a card show. Steinberg had recently sold his retail company and decided to research the elusive right-hander. By 2002 he had written more than 200,000 words but shelved the project for seven years. In 2009, Steinberg returned to his Shocker manuscript and began to shape it into a readable biography. The hiatus worked wonders, as Shocker comes to life in this book.

Steinberg’s research includes photos from Shocker’s relatives and also from his own personal collection. He also delves into many Canadian newspaper sources to document Shocker’s minor-league career. Steinberg leads off several of his chapters with the verse of legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice, which ties into that chapter’s subject matter rather well.

Steinberg also brings out the showman and downright cockiness Shocker displayed when he pitched for the Browns. He “loved the noisy fans” in an opponent’s ballpark and felt energized by their scorn. In 1920 he pulled off a nifty piece of gamesmanship against Ruth in a July 13 game. Shocker struck out 14 batters, and Ruth whiffed three times. It was the second strikeout that raised eyebrows.

When Ruth came to bat, Shocker waved his outfielders in. Spoiling Ruth’s timing with a slow pitch for strike one, he beckoned his outfielders to move in even closer. After Ruth swung and missed for strike two, Shocker brought his outfielders to the back fringe of the infield. After setting up Ruth with a fastball outside the strike zone, Shocker came back with a slow pitch that the baffled Bambino missed for strike three.

It was part of Shocker’s crusade to let Huggins know that he made a mistake trading him to St. Louis in 1918. Indeed, Shocker was eager to pitch against his old teammates, and while he only went 22-25 against them in 53 starts, he still gave the Yankees fits.

Steinberg speculates about how Shocker might have fared had his peak years been with the Yankees and not the Browns. New York finished third in 1920 and then won three straight pennants from 1921 to 1923. Shocker went 91-51 during those seasons in St. Louis, including a 27-12 mark in 1921. From 1920 to 1924, the Browns finished fourth, third, second and fifth in the American League. It’s an intriguing thought, particularly in 1920 and 1924; several well-placed Shocker victories could have resulted in five straight pennants for the Yankees.

There are some marvelous nuggets of information culled from the sportswriters of the day, and Steinberg uses them to great effect. Here’s a colorful, descriptive quote from The Sporting News: “Shocker is a trifle temperamental — headstrong, it might more aptly be called. Like all stars, he wants his way. A Bolshevik? Well, no, it’s not that bad.”

By the end of 1927, Shocker’s physical condition was worsening. In June 1928, shortness of breath and bouts of dizziness caused him to collapse; the Yankees released him on July 4, since “illness had stepped in where age had failed,” in the words of sportswriter Fred Leib. Shocker would be dead two months later.

It was time, Steinberg writes, to tell Shocker’s story. “He’s been waiting for almost ninety years,” he writes.

It was worth the wait. Steinberg presents a fascinating portrait of a pitcher who was respected by his peers but faded into obscurity. This new biography brings the pitcher — and the man — back to life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed