Throw in Hall of Famers Walter Johnson, Bob Feller, Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan, and the overpowering fastball is well-represented in major league history.

Dalkowski might have been faster. But “Dalko,” who died earlier this year at the age of 80, never made it to the major leagues.

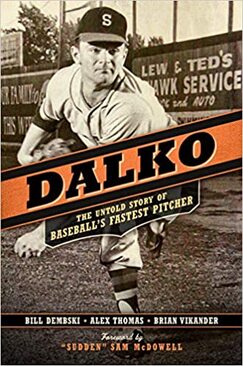

“Every pitch was an all-or-nothing effort, an unhittable strike or an uncontrollable ball,” authors Bill Dembski, Alex Thomas and Brian Vikander write in Dalko: The Untold Story of Baseball’s Fastest Pitcher (Influence Publishers; hardback; $26.95; 304 pages).

It’s true. Dalkowski almost seemed offended if a batter managed a loud foul ball. Unlike the 1949 movie, “It Happens Every Spring,” Dalkowski did not need a mysterious chemical that repelled wood to make him a strikeout king. He was scary fast. He was closer to writer-director Ron Shelton’s fictional erratic pitcher, Nuke LaLoosh, in the 1988 movie, “Bull Durham.” Shelton had been a player in the Orioles’ farm system and had heard the legendary tales about Dalkowski.

“In his sport, he had the equivalent of Michelangelo’s gift but could never finish a painting,” Shelton wrote about Dalkowski in 2009.

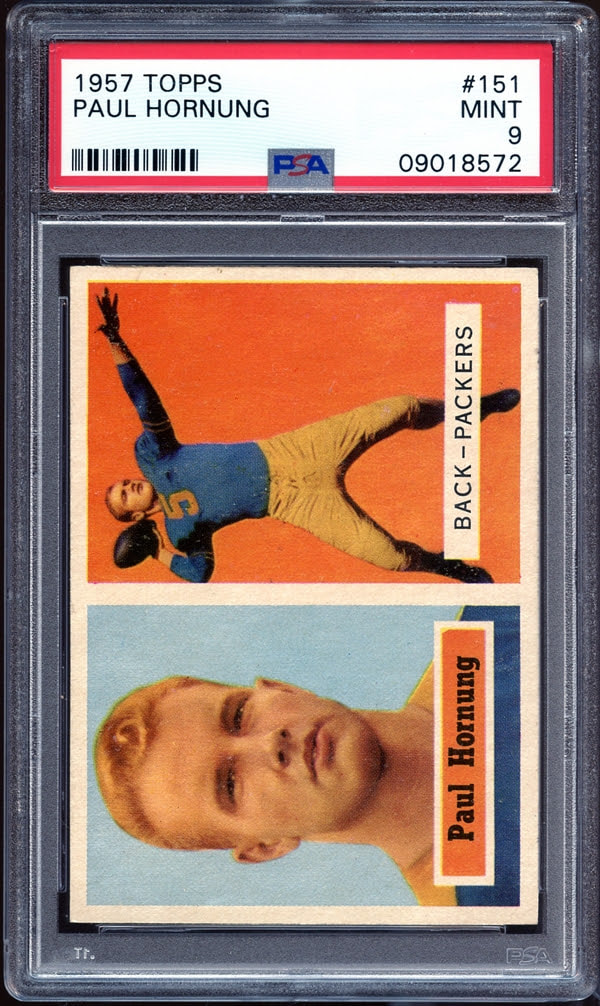

As an 18-year-old in 1957, Dalkowski set an Appalachian League records with 39 wild pitches and 129 walks. However, he set a league record on Aug. 31 for left-handers with a 24-strikeout performance against Wytheville — but also walked 18. That came two weeks after Dalkowski walked 21 batters and had six wild pitches in 7 1/3 innings during a 9-7 loss to Wytheville.

Dalkowski advanced to the Triple-A level twice and even appeared on the brink of cracking the major leagues with the Baltimore Orioles in 1963.

“Ex-Wildman Tames Tigers,” The Miami News noted in a March 13, 1963, headline.

Nine days later, Dalkowski threw three straight strikes past Yankees slugger Roger Maris.

“I’ll bet Maris never names one of his kids Steve,” Steve Barber observed.

Barber was correct.

“Zeus quietly took back his thunderbolt,” Shelton would write.

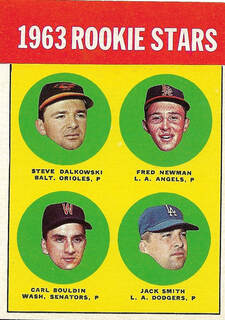

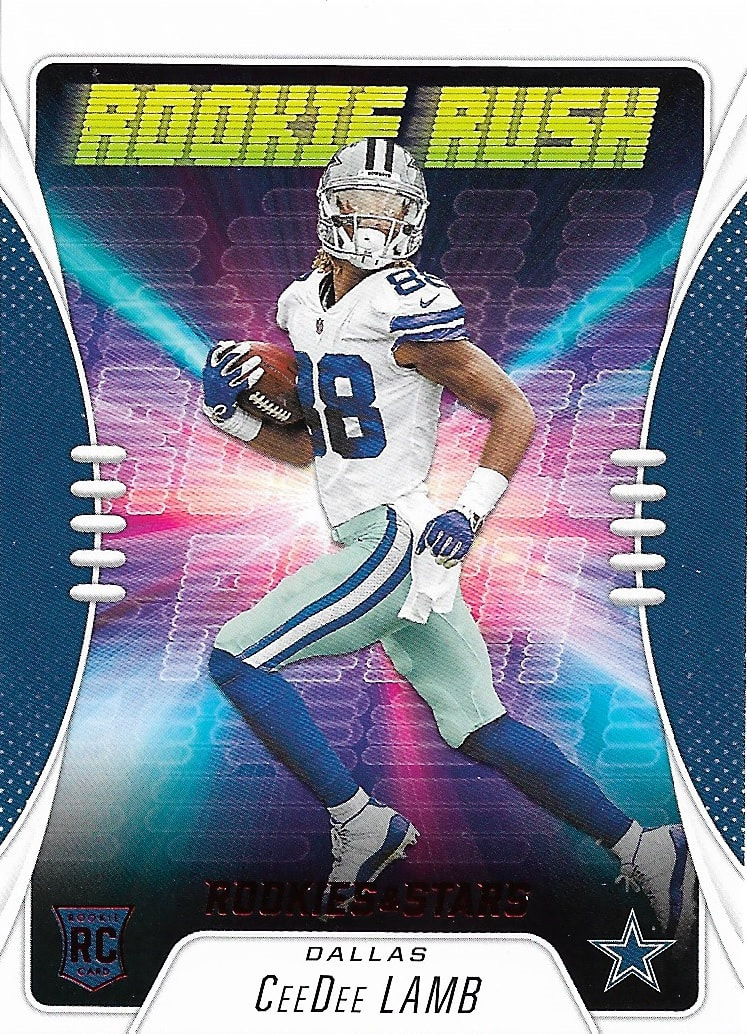

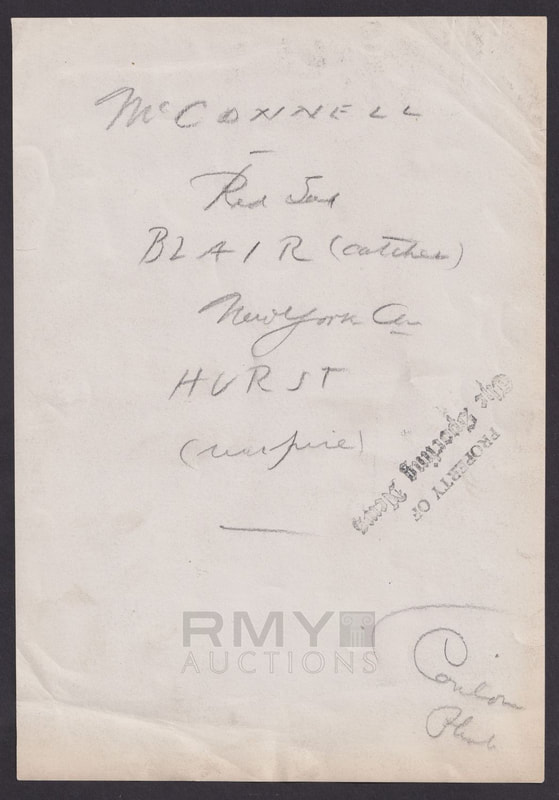

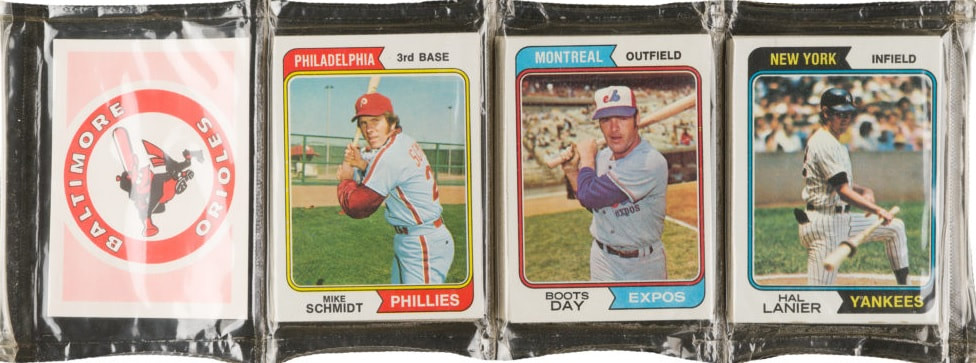

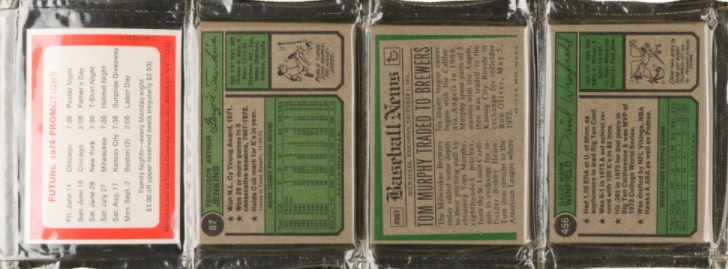

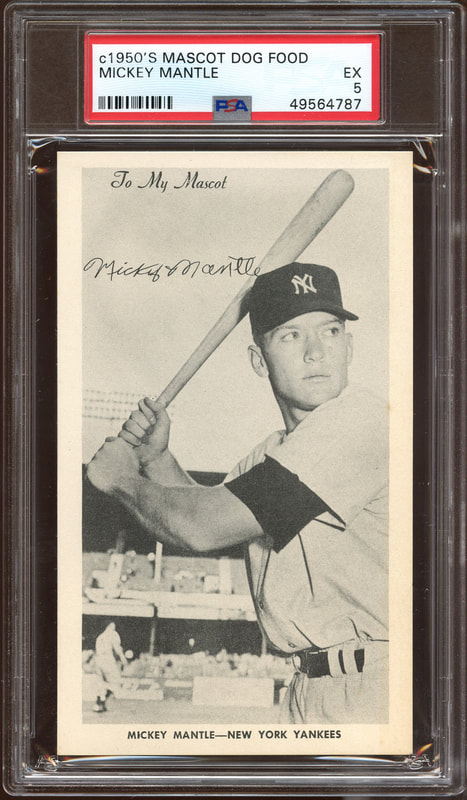

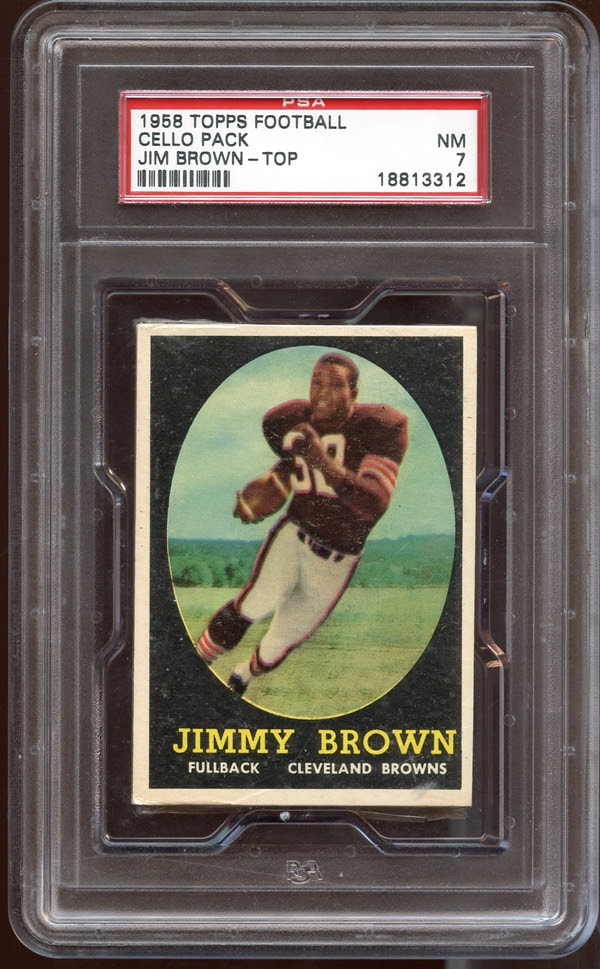

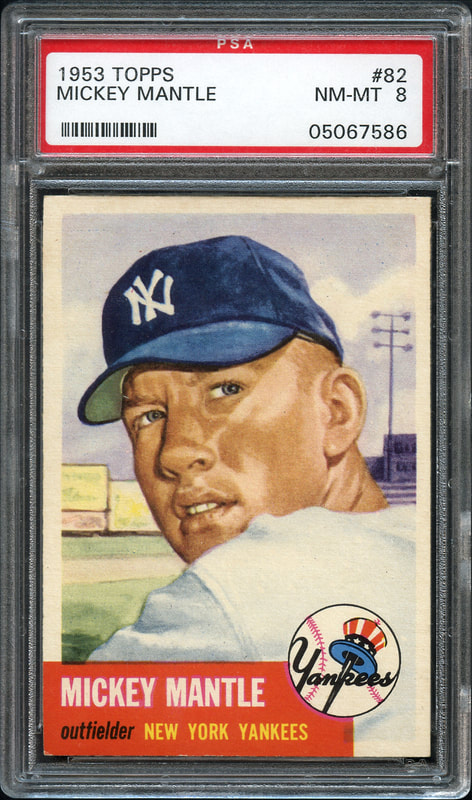

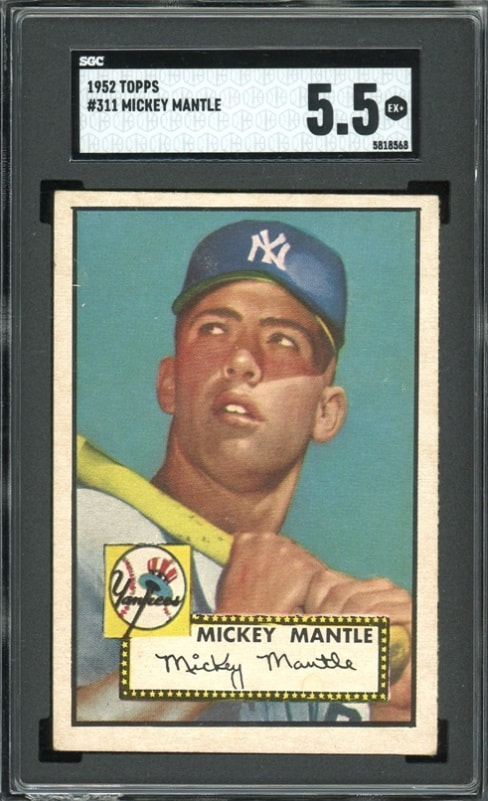

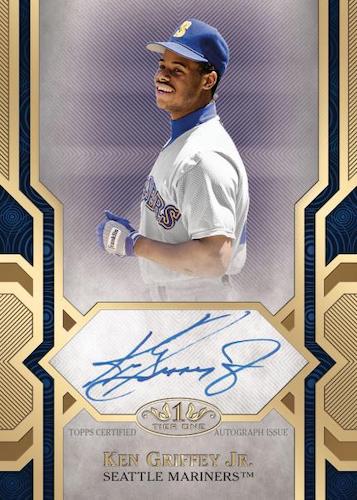

Dalkowski still managed to have a Topps baseball rookie card — No. 493 from the 1963 set. He would not earn a solo card.

Dembski, Thomas and Vikander set out to debunk the myths surrounding Dalkowski, and they do a workmanlike job. They spent four years researching and interviewing, sifting through 55 newspapers and interviewing 27 subjects.

“The true story of Steve Dalkowski — as opposed to the legend — is out there, but it took some doing to find it,” the authors write.

One legend attached to Dalkowski was that his fastball was so explosive, it ripped a player’s ear off.

Not true. As the authors note, Dalkowski, pitching for Kingsport on June 30, 1957, hit Bluefield Dodgers batter Bob Beavers on the top half of his ear, “crushing” it.

“Though the ear was smashed and bloodied, it was not torn off,” the authors write.

According to the Bluefield Daily Telegraph’s story the next day, the incident, reported in the second paragraph of the story, occurred during the sixth inning, and Beavers was in “fair condition” at an area hospital.

The recurring theme the authors put forth is that opposing batters were amazed by Dalkowski’s velocity but were reluctant to step into the batter’s box against him. A batter never knew if a pitch was going to be a letter-high fastball or a pitch that sailed over everyone’s heads and into the stands.

That began when Dalkowski pitched for New Britain High School in Connecticut. He threw back-to-back no-hitters, but kept batters bailing with his unpredictable aim.

“When he was throwing strikes, nobody could touch him,” the authors write. “When his control was off, he didn’t know what to do to get it back.”

As it turned out, nerves and a lack of confidence derailed Dalkowski’s hopes to reach the majors. So did his love for alcohol.

His father drank heavily, and it was not unusual to see Dalkowski accompanying his father to area bars. Some teammates knew about the drinking, believing he was influenced by older players. The young southpaw, “ever friendly and eager to please,” was happy to go drinking, believing it was a way to be accepted.

As events would show, it was the wrong decision.

“I didn’t drink to forget. I just drank,” Dalkowski would say.

The authors hint that on the field, Dalkowski may have been the victim of overcoaching. Several coaches tried to tinker with his mechanics to help with his control, but that only tended to make the situation worse. The only manager or coach who really had a positive influence was future Hall of Famer Earl Weaver, who was Dalkowski’s manager in Elmira, New York.

Weaver believed that Dalkowski “was easily distracted and confused,” adding that the reason he did not improve is that coaches “were trying to tell him too much at once.”

Dalko would eventually resent the attention lavished on his fastball and his legend when he would join a new team or league. “Like I was a freak or something,” Dalkowski told Mark Fleisher of the Elmira Star Gazette in 1979. “I look back at it all and I’m a little disgusted.

“But you can’t cry over spilled milk, can you?”

By 1966, Dalkowski was out of baseball. That began a long decline as the former pitcher battled alcohol, a failed marriage, and finally, the onset of dementia. Several friends tried to rehabilitate him, but Dalkowski always slipped back into a haze of beer or liquor.

The authors note how during his baseball career, Dalkowski was forever broke, borrowing money from his teammates to go drinking. However, on payday, he would make good on his debts, only to borrow money again in a continuing cycle.

Dalkowski died in April 2020 after spending the last 26 years of his life at a nursing home with alcohol-induced dementia. The cause of death was listed as COVID-19 related. He lived long enough to be inducted into the New Britain Sports Hall of Fame.

Dembski, Thomas and Vikander do an excellent job in piecing together the life of a man who had all the physical tools to be a major league pitcher but could never overcome his wildness. Baseball’s hardest thrower lived a hard, sad life.

“A God-gifted rookie who was a lost soul,” the authors write. “Maybe (his gift) was too much. Maybe he never got comfortable with it. Maybe he needed other gifts to handle it.”

“Dalko” is a gift for the baseball historian’s library.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed