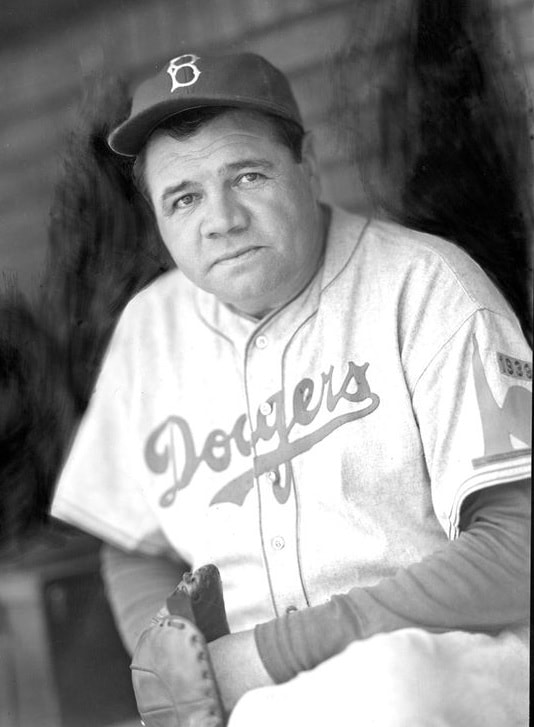

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/auction-offers-chance-to-go-cruising-with-a-babe-uniform/

|

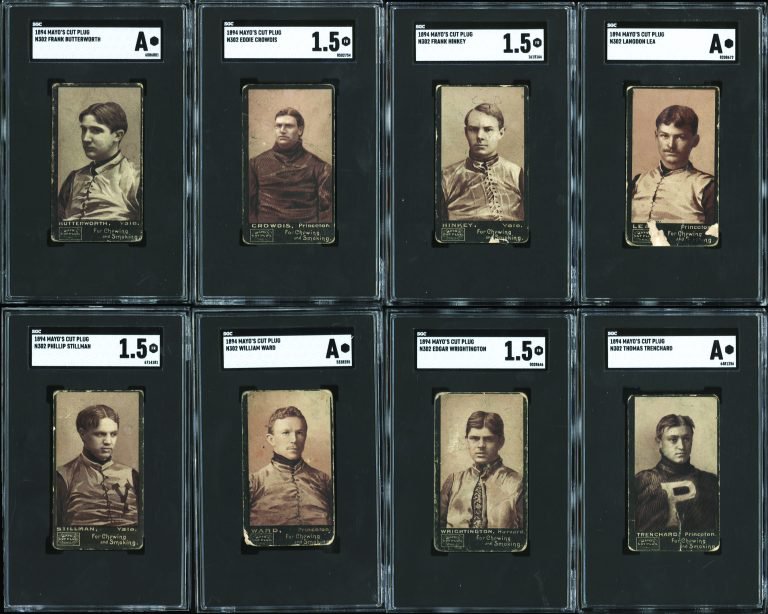

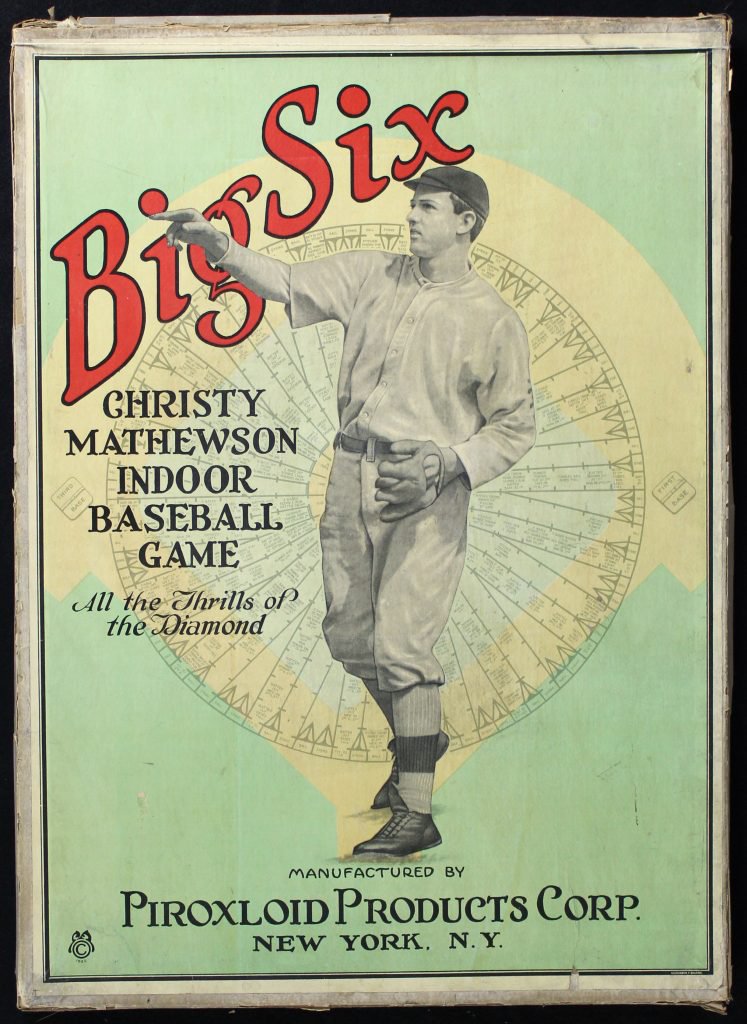

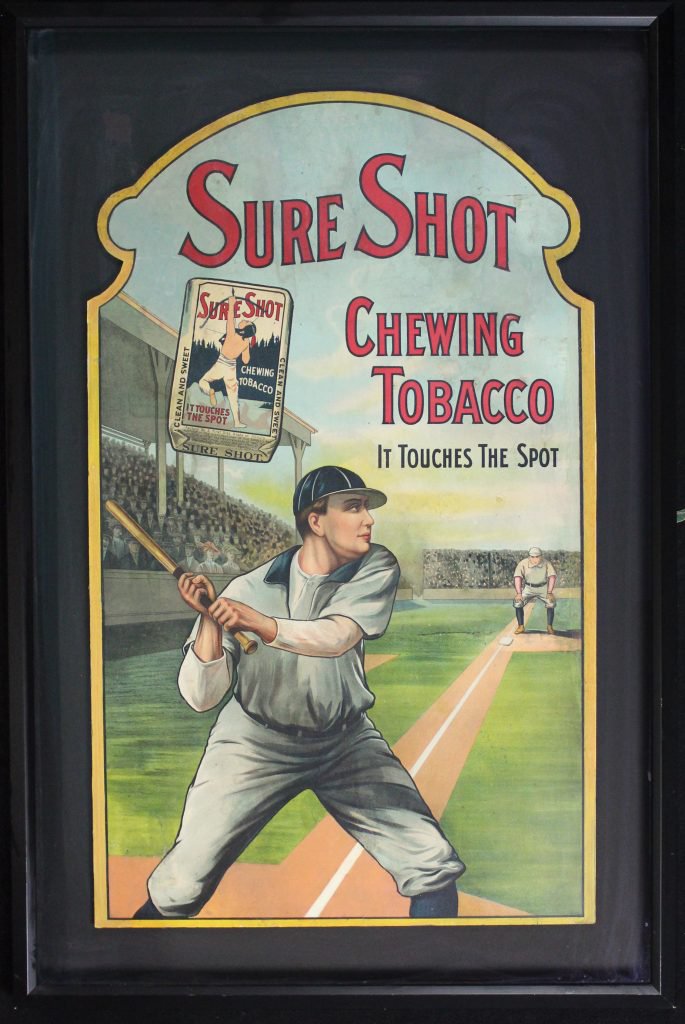

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the collection of Dr. Goodman B. Espy III, which will be auctioned off in November. As a preview, some collectors can view the items on a cruise aboard the Queen Mary 2: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/auction-offers-chance-to-go-cruising-with-a-babe-uniform/

0 Comments

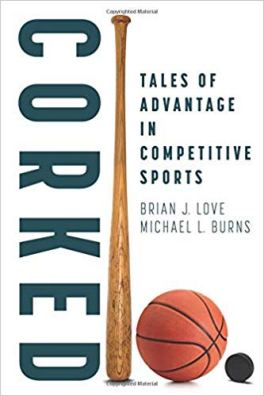

Here's my review of "Corked" that ran on the Sport in American History website:

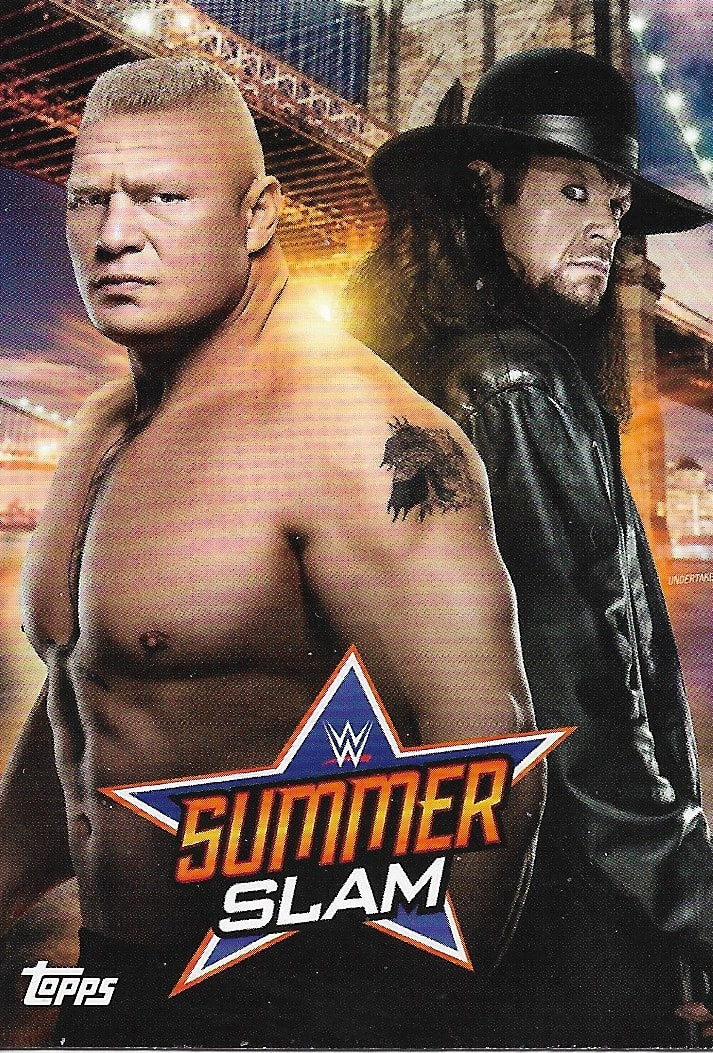

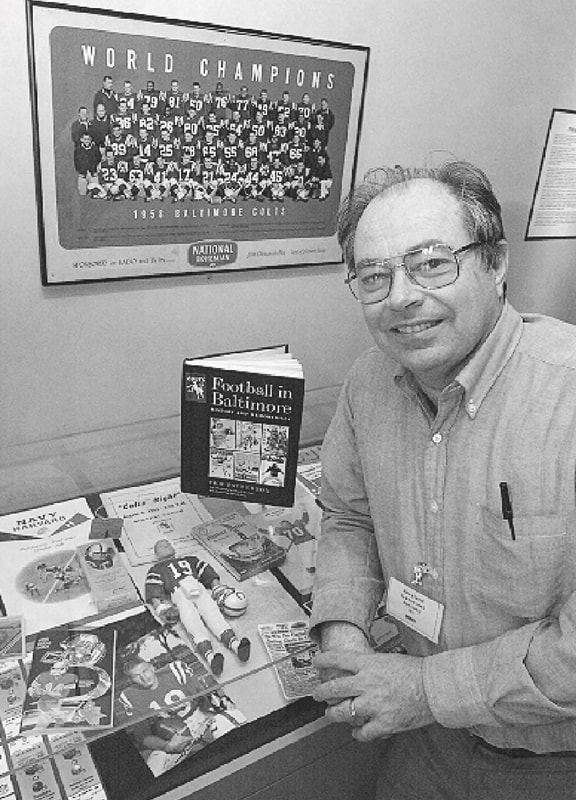

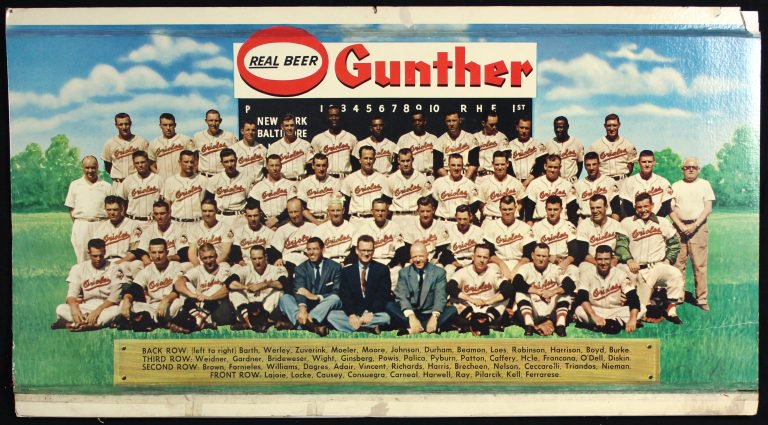

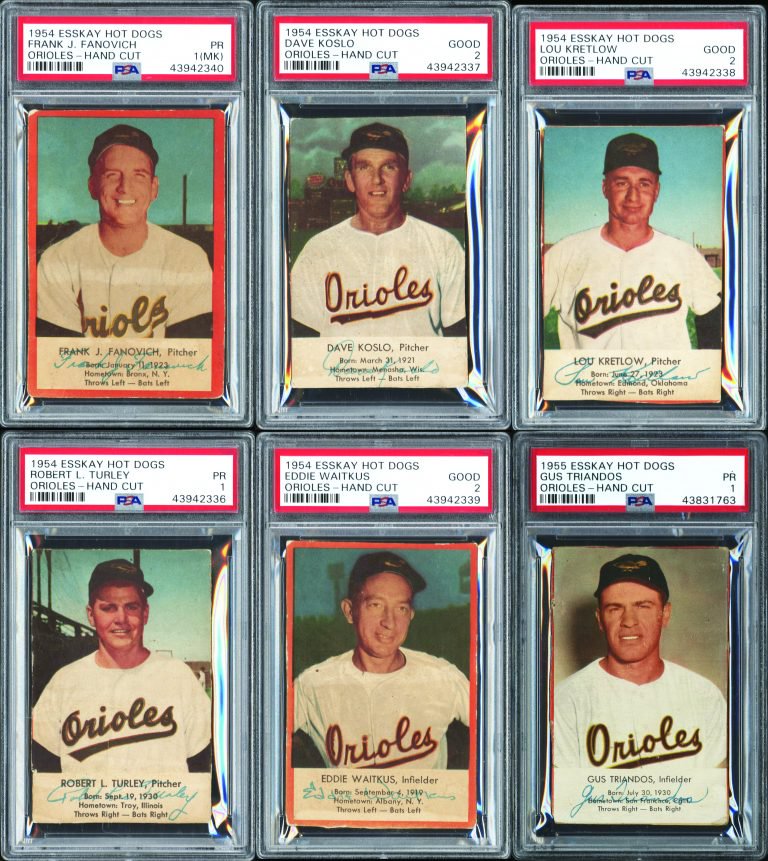

ussporthistory.com/2019/07/27/review-of-corked/  OK, I confess. Like most kids who collected baseball cards during the 1960s, I made fun of Don Mossi’s picture, especially on his 1966 Topps card. Mossi didn’t even play in 1966, but he spent his final season (1965) with the Kansas City Athletics. Mossi, who died July 19 at age 90 in Nampa, Idaho, was a fine left-handed pitcher for 12 seasons. He played for the Cleveland Indians, Detroit Tigers, Chicago White Sox and the Athletics from 1954 to 1965. He was known as “The Sphinx” or simply “Ears.” He had prominent ears and a large nose (hey, I’m of Italian descent, so I can sympathize with the nose), and although he ran a hotel later in life after baseball, his dark complexion and five o’clock shadow made him look like your town’s friendly undertaker. Jim Bouton, writing in Ball Four, noted that Mossi “looked like a cab going down the street with its doors open.” More charitably, Brendan C. Boyd and Fred C. Harris, in their book, The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, described Mossi as having “loving cup ears.” But forget the ears — Mossi was all heart, as a player and as a man. He had a 101-80 record with a 3.43 ERA and saved 50 games. He made 165 career starts and had 55 complete games, and only made three errors. During his rookie season in 1954, Mossi teamed with Ray Narleski to give the Indians a lefty-righty one-two punch out of the bullpen. It would have been hard for Mossi to crack the Indians’ starting rotation in 1954 since it contained future Hall of Famers Early Wynn, Bob Lemon and Bob Feller. Nevertheless, Mossi went 6-1 with a 1.94 ERA and seven saves. He also made three appearances in the 1954 World Series and did not allow a run. Mossi never had a great fastball, but he got by with guile and pinpoint control. He was traded to Detroit, along with Narleski, for Billy Martin, in November 1958. Mossi blossomed as a starter in Detroit, going 17-9 in 1959 and 15-7 in 1961. He had 15 complete games in 1959 and 12 in 1961. On April 11, 1963. Mossi flirted with a perfect game, retiring the first 19 Cleveland Indians he faced before Tony Martinez had an infield hit. Gene Green was the only other Cleveland batter to get a hit, singling in the ninth. Mossi won, 6-1. Lou Mio of the News-Herald in Mansfield, Ohio, wrote that Mossi summoned “his four evangelists — Fast, Change, Slider and Curve”— to dispatch the Indians in 2 hours, 22 minutes. Some players get a dinner held in their honor after retirement. For more than 40 years, Mossi has been celebrated annually on his birthday. In January 1974, Doug Bureman, an assistant in the Cincinnati Reds’ public relations department, was sitting in his apartment with some friends, looking through baseball cards and drinking beer. “We wanted to have a party but we needed an excuse to have one,” Bureman told Bob Hertzel of the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1977. Bureman happened to see Mossi’s card and flipped to the back. He saw that Mossi’s birthdate was Jan. 11, 1929. Bingo. The first annual Don Mossi Birthday Party was born. More than 80 people, paying a dime apiece, showed up for the party. Some of Bureman’s friends baked a birthday cake “that looked just like Don,” and the group made a telephone call to the bemused Mossi at his California home. The second annual party was even bigger. Among the 280 guests attending the party at the Disabled American Veterans hall in Clifton, Ohio, were Reds catcher Johnny Bench and Cincinnati broadcaster Marty Brennaman. Entertainment was provided by the aptly named Don Mossi Blues Band. Mickey Mantle didn’t get this kind of love. At Jefferson High School in Daly City, California, Mossi not only was a baseball star, but also a quarterback for the Indians (a nice coincidence with the team nickname). Described as “a triple threat,” Mossi was named a first-team quarterback to the Peninsula Athletic League in 1946 and 1947. He also kicked extra-point attempts. Mossi was signed by Cleveland and worked his way up the minor league chain, starting with Class C Bakersfield of the California League in 1949. He advanced to Class A ball, and by 1953 was in Double-A with Dallas and Tulsa in the Texas League before breaking into the majors in 1954. His biggest moment in the minor leagues came on Aug. 27, 1950, in Bakersfield, when Mossi married Eunice Bedford at home plate before the Indians’ game against the San Jose Red Sox. Mossi then pitched no-hit ball for 7 2/3 innings in the Indians’ 13-1 victory. He allowed a home run to Sheriff Robinson in the eighth inning but finished with a two-hit victory. Don and Eunice were married for nearly 45 years. Eunice died in June 1995. She was 62. I belong to several online baseball card trading groups. Several years ago, in one of my groups, we had an online discussion about homely looking pictures of players on baseball cards, and Mossi’s name invariably came up. Shortly after that, we received an angry (and profane) letter from one of Mossi’s granddaughters, who admonished us for our lack of sensitivity. If she had seen a photo of us card collectors, she would have realized that we were a homely looking bunch. Kindred spirits, if you will. But we all got her point. After Eunice’s death, Mossi moved to Idaho in 2000 to be closer to his large family. According to his obituary in the Idaho Statesman, Mossi remained busy in his final years by hunting, camping, woodwork and gardening. Above all, he was a family man, cherished by his three children, 12 grandchildren and 25 great-grandchildren. I still have that 1966 Don Mossi card from Topps — actually, two of them. One of them has his autograph on it. It remains one of my favorite cards, but now, for a different reason. Mossi deserved a loving cup — not for his ears, but for his heart and the life he led.  SummerSlam has been a staple of World Wrestling Entertainment since its debut in 1988. It has been the perfect pro wrestling event to keep interest lively during the doldrums of summer, and this year’s event in Toronto on Aug. 11 should be no different. Looking at the present and remembering the past is the focus of the 2019 Topps SummerSlam set. With 100 cards in the base set and a nice sampling of inserts, the set provides a colorful look at the WWE’s top performers. The 100-card base set is divided into two parts: a 50-card set of stars that competed in last year’s SummerSlam event in Brooklyn, New York, and 50 cards of key matches from the 2018 event. As usual, I bought a blaster box, which included 10 packs. There are seven cards to a pack, and there is a pack that includes either a relic, autograph, or even an auto-relic. In addition, there is a pack containing four Women’s Evolution insert cards.  In the blaster I opened, I pulled 25 cards of the individual stars and 22 cards of the SummerSlam Leadup. The design for card Nos. 1-50 shows the wrestler in a posed shot, with the Topps logo in the upper left-hand corner and the WWE logo in the top right-hand corner. The background behind each wrestler is splashy and bold, with vivid orange and yellow tones. The SummerSlam logo dominates the card beneath the photo of the wrestlers. The card backs include a 10-line biography, with side notes that diehard WWE fans will recognize. So, fans can learn more about the Phenomenal One (AJ Styles), the wrestler whose fans sang a version of “Seven Member Army” (Elias), the Boss (Sasha Banks) and The Lone Wolf (Baron Corbin). The SummerSlam Leadup is more action-oriented on the card front, highlighting big matches from 2018. The card back includes a seven-line summary of a key match. Topps continues its yearlong Ronda Rousey Spotlight series with a third installment in the SummerSlam product. Previous cards can be found in the 2019 Topps’ WWE Road to WrestleMania and the 2019 Topps Raw sets. There was one Rousey card in the blaster I opened.  The nice part about this product is getting a hot card, even from a blaster. The card I pulled was SummerSlam 2018 Event-Used Mat relic card that featured Seth Rollins on the front. The inserts are vivid and show some imagination. The SummerSlam Posters Spotlight is a four-card series that highlights reprints of the promotional posters for previous Summer Slams. I pulled two of these cards from the blaster box I bought. One featured a reprint of a 2015 poster that featured Brock Lesnar and the Undertaker, while the other was a 2018 reprint that featured Lesnar, Alexa Bliss, Rousey and Roman Reigns. The Greatest SummerSlam Matches & Moments insert comes as advertised, with 40 of the biggest moments in the event’s history. I pulled 10 of the 40 inserts in the subset, and those cards included the 1991 “wedding” between Randy Savage and Miss Elizabeth, Ric Flair’s “I Quit” victory against Mick Foley in 2006, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin winning the Intercontinental title in 1997, and Dusty Rhodes’ victory against the Honky Tonk Man in a 1989 SummerSlam bout. I pulled 10 of the 25 SummerSlam All-Star inserts, including cards of Lesnar, Bret Hart, Edge, the Hart Foundation and D-Generation X. As advertised, there were four Women’s Evolution cards in a special pack. There are only six different ones, and the cards I pulled included Bliss, Banks and Charlotte Flair, a solo card of Flair and a Smackdown Women’s Championship card. Topps — and the WWE — continue to see the value in promoting the women wrestlers in the company, and that’s a good thing. Topps and the WWE continue to have a successful partnership with its rotating sets of cards each year. The cards include action, big stars, and plenty of inserts. The inclusion of relics and/or autographs in blaster boxes make this set fun to buy and collect.  “Luck is the residue of design” is a quote that has been attributed to baseball executive Branch Rickey. “The Mahatma” stressed that things worthwhile “generally don’t just happen,” and that “luck is a fact but should not be a factor.” Author-poet Natasha Josefowitz might have said it better, though. Luck, she said, “is being in the right place at the right time.” But, “location and timing are to some extent under our control.” Joe Wessel fits those descriptions. Wessel, a Tampa businessman, has been an athlete and a coach. He is a family man and has a knack for networking. He also has a wonderful story to tell. Wessel enjoyed playing golf, and, as luck would have it, roomed with Steve Nicklaus, the son of PGA Tour immortal Jack Nicklaus, while he attended Florida State University during the early 1980s. A round of golf that resulted in a broken putter led to series of events that allowed Wessel and his father to play a round of golf with Jack and Steve Nicklaus — and not just at any course. They played at Augusta National Golf Club. How Wessel got to play the fabled course that hosts The Masters is a key element in White Fang and the Golden Bear: A Father-and-Son Journey on the Golf Course and Beyond (Skyhorse Publishing; hardback; $19.99; 181 pages). Wessel, with some collaboration from veteran author (and former Tampa Tribune sportswriter) Bill Chastain, crafts a nice tale while paying tribute to his father, Louis Wessel, who gave him “the ultimate lesson” on how to be a leader. The elder Wessel did that by his passion and work ethic, simply leading by example. It’s a powerful story, and much of it has to do with Wessel’s relationship with his dad. Wessel quotes snippets of letters he wrote home and chronicles the life and career of his father. Louis Wessel enlisted in the Army during World War II when he was 15 and led a life whose purpose “always seemed to come to him effortlessly and with clarity.” The elder Wessel also had a catalog of favorite sayings, which his son mentions in the book’s appendix. One even had hunting overtones. “Keep your eye on the bird,” Louis Wessel would tell his son. “You haven’t shot it dead yet. Keep your focus. Eliminate the distractions.” That’s a perfect philosophy for concentrating in golf. The best players have it. Jack Nicklaus was always focused, and the tale surrounding White Fang is a good example. It is the name given to a putter Jack Nicklaus used to win the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol. The putter, a Bull’s Eye brand painted white, became lost in the shuffle of clubs the Golden Bear used to win his 18 major golf championships. It ended up in the hands of Steve Nicklaus during his time at FSU, and the younger Nicklaus gave the club to Wessel when he broke his own putter while tossing it in the air after a particularly frustrating shot. Wessel kept the club, not knowing its significance until years later. Wessel was Steve Nicklaus’ teammate and roommate at FSU, and a special teams demon during his senior season with the Seminoles. He blocked five kicks during the 1984 season, converting three of them into touchdowns, an NCAA record. Wessel tells the story of meeting Jack Nicklaus for the first time in 1983. The Golden Bear grabbed Wessel by the arm and pulled him into a back room and without missing a beat, asked him a question about his son, Steve. “How are you two getting along?” Nicklaus asked. Wessel thought it was an odd question since he and the younger Nicklaus had only been roommates for a month. “We were still on our honeymoon!” Wessel wrote. Looking back, Wessel realized what had happened. “I realized his thought process began with caring about his kids,” Wessel wrote. “That spoke volumes about how ingrained he was in his family life.” A quick diversion for a personal story. Was Nicklaus devoted to his children? Most definitely. It was common to see Nicklaus at his sons’ football games and his daughter’s volleyball matches and softball games. As a sportswriter during the early 1980s at The Stuart News, I’d seen Nicklaus stalk the sidelines at football games to encourage his sons. He might have been famous, but during his kids’ games, Nicklaus reacted as most parents did. It also was not unusual for Nicklaus' wife, Barbara, to work at the scorer’s table when her daughter, Nan, played volleyball. The Benjamin School in North Palm Beach is where the Nicklaus children attended high school. In the early 1980s, the Buccaneers ventured to John Carroll High School in Fort Pierce. Barbara Nicklaus was at the scorer’s table, and Jack Nicklaus was in the stands to watch Nan as Benjamin prepared to play a traditionally powerful Golden Rams squad. My boss at The Stuart News, J.T. Harris, approached Jack Nicklaus, who initially waved him away, saying, “I don’t want to talk about golf.” Harris was prepared, however, telling Nicklaus that he wanted to talk about Nan’s progress as a volleyball player. That did the trick. Harris got the interview, a different angle and a nice exclusive. Wessel’s involvement in sports as a youth was helped by the friendships of his mother — and his own friend-making ability — with the sons of Miami Dolphins head coach Don Shula and his assistant Howard Schnellenberger. Wessel would help out at the Dolphins’ training camp, and that got him special time with players like quarterback Earl Morrall. Wessel even got to meet one of Schnellenberger’s neighbors at a party, a young musician named Harry Wayne Casey. Casey was at the height of his popularity as the lead singer for KC and the Sunshine Band, but Wessel regarded him as a regular guy and even got the musician a deal on a slalom ski. Wessel’s college playing career ended after the 1984 Citrus Bowl (a 17-17 tie with Georgia), but he stayed in athletics as an assistant coach. He worked at LSU and Notre Dame, then jumped to the pros to work for the Cincinnati Bengals and Philadelphia Eagles. Wessel’s renewed his connection with White Fang after talking with his father, who noticed the putter and vaguely recalled Jack Nicklaus was looking for two of his famous clubs. White Fang was one of them. In April 1983, Wessel attended Steve Nicklaus’ 40th birthday party. He told Jack Nicklaus, “I may have a club that might be yours.” Intrigued, the six-time Masters champion wanted to see it. When he realized it was White Fang, he asked to have it back. Wessel obliged, but when Nicklaus offered to send him a set of clubs as compensation, he realized he was in the right place at the right time. “You’re not getting off that easy,” Wessel told Nicklaus. “You get Steve, and I’ll get my Dad. Let’s go to Augusta, and we’ll call it even.” Nicklaus agreed, and the match was on. The book is sentimental and sweet. Chastain’s role was to fill in the gaps by speaking with some of the main characters Wessel encountered during his athletic career. Chastain, who is a fine storyteller in his own right, did the necessary research on White Fang, but steps back and allows Wessel to control the narrative. Jack Nicklaus wrote the foreword to White Fang and the Golden Bear. He notes that Joe Wessel “had a special relationship with his dad,” adding that setting up the foursome at Augusta was “a small part in their life together” that nonetheless brought him “pure joy.” White Fang and the Golden Bear is a brief story, but a special one. It’s a story filled with pure joy, good advice, funny stories — and some extraordinary luck. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Ted Patterson, the former Baltimore sportscaster whose massive collection is heading to auction this summer.

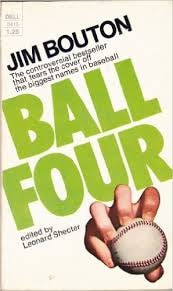

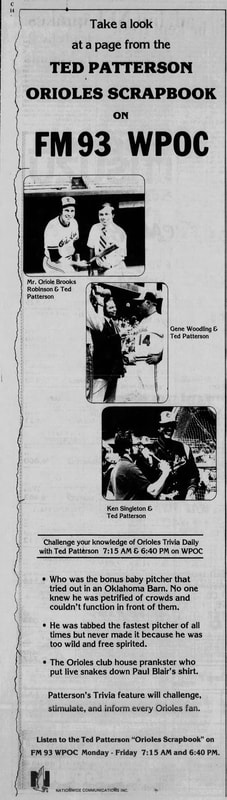

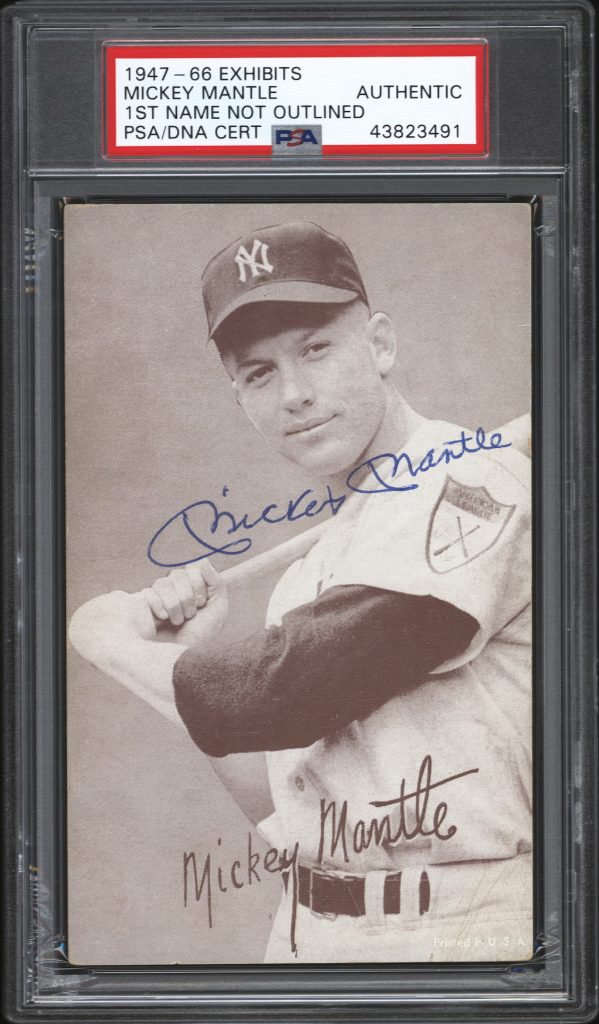

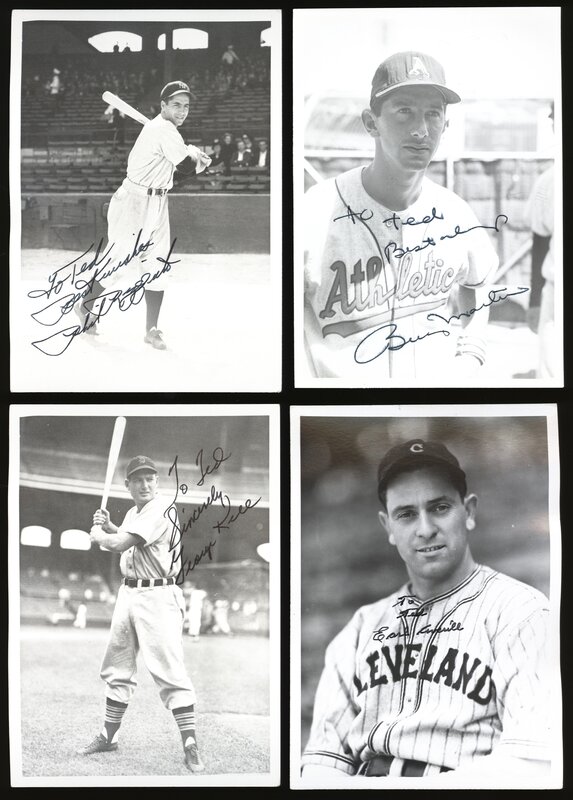

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/ex-broadcaster-ted-pattersons-huge-collection-part-of-love-of-the-game-summer-auction/  Jim Bouton’s diary entry 50 years ago in Ball Four, on July 10, 1969, recounted a prank played on Seattle Pilots pitcher Fred Talbot. I went back and reread that entry after learning that Bouton had died Wednesday at his Massachusetts home at the age of 80. The prank the Pilots played on Talbot, where he got a letter from a fan promising $5,000 after the fan won a contest, was hilarious, and so was Bouton’s narrative. It was the kind of insider stuff that, as a 13-year-old in 1970, I craved to read about. Baseball players were my heroes, but it was fun to learn these guys weren’t saints. Ball Four showed the locker room as it really was, with young men who not only were talented athletes, but also drinkers, pill poppers and skirt chasers. Players could be mean, crude, profane, tough or silly. They could play cruel jokes, kiss each other on the lips, yell lewd things to women while riding on the team bus and grumble about their lack of playing time. Managers and coaches could be distant or simply out of touch. Those players and coaches also could be thoughtful, political and intelligent. Bouton was a decent pitcher for the New York Yankees, but it was his keen eye for detail and his groundbreaking book, Ball Four, that made him a baseball legend. Certainly, the baseball establishment did not take too kindly to Bouton’s revelations — in fact, he was vilified and shunned by players and raked across the coals by sportswriters. New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote that Bouton was a “social leper,” and unwittingly gave the budding author the title for his second book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally. Much of the invective leveled at Bouton came because he violated the unwritten code of the baseball clubhouse, an athletic sort of omerta: “What you see here, what you hear here, what happens here, stays here.” Well, Bouton opened his mouth, and the baseball establishment was upset. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn tried to get Bouton to recant his book, but he refused. What Kuhn did not realize was that every bit of ink written about his efforts to squash Bouton’s book helped sell more copies of Ball Four. Looking back, here’s what I think. I believe many of the writers who followed the teams even into the 1960s had an agreement — unwritten or otherwise — to keep personal items out of the newspapers. How else to explain how many of Babe Ruth’s indiscretions never became public — and he was no saint, by any means. There had been some sportswriters emerging in the 1960s — Leonard Shecter, who helped Bouton write Ball Four, was one — who was part of the new breed of sports journalists referred to as chipmunks, because of their incessant chattering and pointed questions. These younger writers dug deeper and asked tougher questions. When Bouton wrote Ball Four, suddenly all bets were off — and the old guard of sportswriters was forced to become reporters and journalists. Never mind that Bouton, nicknamed the Bulldog early in his career, won 21 games in 1963 and a pair of World Series games in 1964 after winning 18 games that season. He was persona non grata in the eyes of the baseball establishment after writing Ball Four. I was always surprised by Dick Young’s reaction to the book since he was the prototype of the sportswriter who went into the locker rooms and asked questions without dewy-eyed awe. His work during the 1940s and ’50s with the Daily News was the gold standard for future beat reporters. So why the animosity? Who knows — maybe Young wanted to write the “tell-all” book about baseball, and Bouton beat him to the punch. Ball Four was inspired to a degree by another pitcher’s diary — The Long Season, published in 1960 by Jim Brosnan. While Brosnan kept the locker room details to a minimum, Bouton used a no-holds-barred approach.  Even though I own the hardback version of Ball Four with all of its updates, I still have the dog-eared paperback I read as a kid. Even though I own the hardback version of Ball Four with all of its updates, I still have the dog-eared paperback I read as a kid. Some of the portraits he painted were tremendous. Pilots manager Joe Schultz, who would tell his players to go out and win “and pound that Budweiser” after the game. Or Gary Bell, whose response at a pregame meeting about every opposing hitter was “Smoke ’em inside.” "Gary Bell is a beautiful man," Bouton wrote. Younger players like Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall were blossoming into men who would not follow the old guard blindly. And what lines. Hovley came up to Bouton in spring training and told him that “to a pitcher a base hit is the perfect example of negative feedback.” The talk about “greenies” — amphetamines — was prevalent throughout the book. At one point, Bouton asked teammate Don Mincher how prevalent greenies were. Did half of the player take them? More than that? “Hell, a lot more than half,” Mincher said. “Just about the whole Baltimore team takes them. Most of the Tigers. Most of the guys on this club. And that’s what I know for sure.” The biggest controversy that came out of Ball Four was Bouton’s portrayal of his former teammate, Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle. Mantle’s retirement in March 1969 sparked memories from Bouton — some good, others that were revelations to many fans. “On the one hand I really liked his sense of humor and his boyishness,” Bouton wrote. “… On the other hand there were all those times when he’d push little kids aside when they wanted his autograph.” It was only a few pages of memories, but it caused anger among players and fan who were not used to seeing their heroes, warts and all. Mantle was my favorite player when I was growing up, but Bouton’s revelations did not offend me in the least. It made The Mick more human, in my view. Read The Last Boy by award-winning author Jane Leavy. There is more detail in that book about Mantle — good and bad — than Bouton ever published in Ball Four. Leavy also gives Babe Ruth the same no-holds-barred treatment in her latest book, The Big Fella. Bouton turned out to be a better author than a pitcher, and baseball never really forgave him for breaking the code of silence. He reconciled with Mickey Mantle before the slugger’s death in 1995, and the Yankees invited him to an Old Timer’s Game in 1988 after his son, Michael, wrote an editorial in The New York Times on Father’s Day that year, telling the team to let bygones be bygones. The cruelest fate for Bouton is that a man of his wit and intelligence was felled by dementia. He suffered a stroke in 2012 and was plagued by a brain disease that was discovered in 2017. One of baseball’s great voices has been silenced, but Bouton’s legacy lives on through Ball Four. His love for the game was deep, as he wrote in the final paragraph of that 1970 bestseller. "You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time," he wrote. RIP, Jim Bouton. Your final pitch was a strike, and the baseball establishment whiffed.  The 2019 Bowman Platinum baseball card set is a retail-exclusive set that offers prospects, rookies and current major league stars. And if you like shiny cards, this one will shimmer for you. You can buy the cards at your local Walmart, or from the store’s website. I bought a blaster box, contains seven packs, with four cards to a pack. There is an extra pack that includes four ice parallels. The base set consists of 100 cards of MLB stars and rookies, plus four short printed cards of Pete Alonso, Eloy Jimenez, Vladimir Guerrero Jr., and Fernando Tatis Jr. The short prints take the place of four common cards in the base set. In the blaster box I bought, I pulled 16 base cards. The card design has the Bowman logo in the top left-hand corner, with the player’s name and team beneath an action photo of the player. The player’s position is situated in the lower right-hand corner of the card front.  The photos are sharp, and the backgrounds are purposely blurred to make the player’s image pop. The right-hand side of the cards is adorned with silver parallelograms (very narrow ones) that stretch vertically from top to almost the bottom. The card backs are clean, with records showcasing a career-best season, 2018 statistics and career totals. Beneath that is a “Platinum Batting Moment” — or “Platinum Pitching Moment,” a six-line highlight from a 2018 performance. There are more parallel lines and crisscrossing lines in varying shades of gray that frame the white box containing the statistics and biographies. In addition to the base cards, there are 100 Top Prospect cards. The design is slightly different on the card front, with the Bowman logo in the top right-hand corner and the player’s position in the lower left-hand corner. The parallel lines are there, too, but form a different pattern. The card backs also have a six-line biography, with 2018 and career statistics above them. I pulled eight of these cards. The ice parallels I pulled were Astros star Jose Altuve, Astros prospect Freudis Nova, Mets prospect Shervyen Newton and Athletics outfielder Ramon Laureano. The parallels are very shiny, with a glittery background that looks like twinkling lights. The scan of Altuve included in this review really does not do the card justice; it looks much nicer in person. A nice addition to this blaster box was a sticker autograph card of Cubs pitching prospect and former Auburn University star Keegan Thompson. I also pulled three inserts: A Renowned Rookies card of Michael Kopech, a Platinum Presence card of Rhys Hoskins, and a Prismatic Prodigies card of Nick Madrigal. If you love shiny cards, Bowman Platinum is a nice product to collect. The design is crisp and clean, with no gaudy embellishments. In a word, tasteful. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about possible legal action that could be taken against "card doctors."

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/legal-remedies-for-victims-in-grading-scandals-can-be-a-difficult-process/  There is reverence attached to the New York Yankees dynasty of the late 1990s and early 2000s. And deservedly so. From 1996 to 2003, the Yankees went to six World Series, winning four of them.' The “Core Four” of Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte and Jorge Posada exemplified the “Yankee Way” that originated in the 1930s when another dynasty under manager Joe McCarthy won five World Series during the 1930s. But several postseason disappointments — including the meltdown in the 2004 ALCS — made it clear the old guard needed some new blood. That is what happened in 2009. The Yankees opened a new ballpark, and the team opened its wallet to bring in some key players. The result was the Yankees’ 40th American League pennant and 27th World Series title. Authors Mark Feinsand and Bryan Hoch take a fresh approach and connect solidly in Mission 27: A New Boss, A New Ballpark, and One Last Ring for the Yankees’ Core Four (Triumph Books; hardback; $27.95; 287 pages). Feinsand covered the Yankees during the 2009 season for the New York Daily News and currently is an executive reporter for MLB.com. Hoch, meanwhile, has covered the Yankees for MLB.com since 2007. The Yankees traditionally have won pennants in bunches, so the 2009 flag represented a season that stood by itself. Certainly, the Yankees believed they had the personnel for another run, but it didn’t happen even though the team reached the postseason after the ’09 season. What makes this book such an interesting read is that Feinsand and Hoch widen their focus beyond the Core Four. That’s because there are so many interesting, free-wheeling characters — Nick Swisher (who wrote the book’s foreword), Mark Teixeira, Johnny Damon, CC Sabathia and A.J. Burnett, to name a few. There were many key moments in that season, but one of the biggest happened before spring training ever began. General manager Brian Cashman’s ability to convince Sabathia to come to New York was huge, not only because of his pitching ability, but also because of his knack for creating a convivial clubhouse. Feinsand and Hoch note that Sabathia was not sold on signing with the Yankees, but Cashman convinced him because the pitcher was “a strong, team-first personality” who could help “mend a clubhouse in need of a makeover.” Sabathia was concerned because he’d heard the Yankees had a broken clubhouse, and Cashman did not mince words. “That’s one of the reasons we’re talking to you,” Cashman told Sabathia. “Not because of who you are as a player but someone who brings people together.” Swisher is the unsung hero of Mission 27, a player with a strong, bubbling personality that fit in well with a winning team. It was easy for Cashman to pry Swisher away from the White Sox, where the first baseman did not mesh with manager Ozzie Guillen and the Chicago coaching staff. Teixeira, meanwhile, was a surprise acquisition. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s on!’ That was huge,” hitting coach Kevin Long told the authors. “This was a big piece, and we knew it. We knew how valuable Tex was.” Signing a new group of free-spirited players allowed Alex Rodriguez to relax and bond with players outside the Core Four. Whether he was ever accepted in the Core Four axis is open to debate, but Rodriguez realized he could bond with other players who could pick up the team. A-Rod could relax, and that would be the difference. Rodriguez had a rocky start before the season, holding an awkward news conference during spring training to address steroid use. No one was comfortable, and although the team leaders stood behind Rodriguez, their body language made it clear they did not necessarily stand with him. An injury that hampered Rodriguez early in the season also was a concern. Feinsand and Hoch excel at bringing out details that led to the Yankees meshing as a group. In the chapter called “A Visit From the Principal,” Cashman makes an unannounced trip to Atlanta in late June and reads the Yankees the riot act — in a calm, effective tone. “His missive cut straight to the point: You’re better than this. Prove it,” the authors write of Cashman, who never raised his voice “from its usual peppy monotone” during the meeting. “There was no need to; the results spoke volumes,” the authors write. “You don’t have to yell to get your point across,” Teixeira said. “Some guys just have a look, a tone. Cash had both.” The second key event was a birthday party Rodriguez threw at his mansion in Rye, New York. It was a swanky affair, with A-listers like Kate Hudson (A-Rod’s girlfriend at the time) and rapper Jay-Z. What made the party notable was the move away from elegance to just plain fun. Rodriguez, on a suggestion from Sabathia and Burnett, blew out the candles to his birthday cake and then jumped, fully clothed in his expensive threads, into his Olympic-sized swimming pool. Even manager Joe Girardi jumped into the pool. “For Rodriguez, the acceptance he felt on the night of birthday party offered another indication that he was moving past his early season drama,” the authors write. Feinsand and Hoch compare A-Rod to the Andy Dufresne character from The Shawshank Redemption, “who crawled through a river of sewage and came out clean on the other side.” Amazingly, the Cashman dress-down and A-Rod party were not discovered during the season; imagine what fun the New York tabloids would have had with that. Feinsand and Hoch, both fine reporters, did not have an inkling, and it was only through their research for Mission 27 that these fascinating nuggets came to light. There are some good anecdotes about Burnett, who smashed whipped cream pies into the faces of players who were being interviewed on postgame shows for their heroics during the game. That helped puncture the myth of the haughty Yankees and injected some fun into the equation. Guys like Burnett and Damon kept the clubhouse loose. “Johnny Damon was a guy I always tell people took us from being the uptight Goldman Sachs executives to more of a kind of college frat house,” Rodriguez tells the authors. Still Burnett had his issues with Posada, and the two battery mates could never work smoothly together. Now, Burnett speaks with regret about Girardi’s decision to have Jose Molina catch him, instead of Posada. The emotional catcher remains bitter about it. “I felt like he stabbed me in the back,” Posada tells the authors. “It hurt me deeply.” Molina, for his part, said he did not feel sorry for Posada and basically said the catcher needed to get over it. “Posada’s griping behind closed doors rubbed Molina the wrong way,” the authors write. “I wasn’t mad; I was just kind of disappointed because a teammate is a teammate in the good times and the bad,” Molina told the authors. “We’re all tough athletes, but everyone’s got a heart,” Burnett told the authors. “I could tell his was hurt and I hope he knew mine was.” The book opens with an oral history, with players, coaches and personnel recalling the Yankees’ World Series-clinching win on Nov. 4, 2009. The biggest takeaway from that chapter was the injury Rivera was fighting. The all-time saves leader had a strained left oblique, and no one — reporters, and especially the Philadelphia Phillies, trying to save alive in the Series — knew about it. “Every time you throw a pitch, it feels like a knife,” Rivera tells the authors. “That was pain. That wasn’t soreness. That’s pain.” The authors were blessed with cooperation from most of the players and executives from that 2009 squad. Jeter is a notable exception, although he is quoted in several places. But the other three Core Four players were happy to speak with Feinsand and Hoch, and it helps give the reader a unique perspective about the pressure that follows players who don the pinstripes. Rodriguez was also particularly candid, which gave the book more heft. It’s not an easy job. Mission 27 is a detailed, behind-the-scenes look at the most glamorous franchise in the major leagues. Feinsand and Hoch present an engaging narrative, rich with detail and firsthand perspective. Even if you are not a Yankees fan, you can still appreciate the hard work and attention to detail. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed