Author-poet Natasha Josefowitz might have said it better, though. Luck, she said, “is being in the right place at the right time.” But, “location and timing are to some extent under our control.”

Joe Wessel fits those descriptions.

Wessel, a Tampa businessman, has been an athlete and a coach. He is a family man and has a knack for networking. He also has a wonderful story to tell.

Wessel enjoyed playing golf, and, as luck would have it, roomed with Steve Nicklaus, the son of PGA Tour immortal Jack Nicklaus, while he attended Florida State University during the early 1980s.

A round of golf that resulted in a broken putter led to series of events that allowed Wessel and his father to play a round of golf with Jack and Steve Nicklaus — and not just at any course.

They played at Augusta National Golf Club.

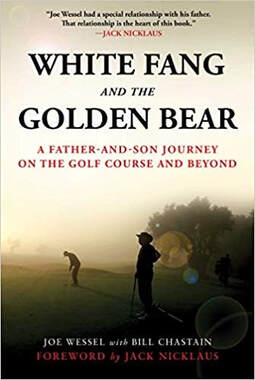

How Wessel got to play the fabled course that hosts The Masters is a key element in White Fang and the Golden Bear: A Father-and-Son Journey on the Golf Course and Beyond (Skyhorse Publishing; hardback; $19.99; 181 pages). Wessel, with some collaboration from veteran author (and former Tampa Tribune sportswriter) Bill Chastain, crafts a nice tale while paying tribute to his father, Louis Wessel, who gave him “the ultimate lesson” on how to be a leader. The elder Wessel did that by his passion and work ethic, simply leading by example.

It’s a powerful story, and much of it has to do with Wessel’s relationship with his dad. Wessel quotes snippets of letters he wrote home and chronicles the life and career of his father. Louis Wessel enlisted in the Army during World War II when he was 15 and led a life whose purpose “always seemed to come to him effortlessly and with clarity.”

The elder Wessel also had a catalog of favorite sayings, which his son mentions in the book’s appendix. One even had hunting overtones.

“Keep your eye on the bird,” Louis Wessel would tell his son. “You haven’t shot it dead yet. Keep your focus. Eliminate the distractions.”

That’s a perfect philosophy for concentrating in golf. The best players have it.

Jack Nicklaus was always focused, and the tale surrounding White Fang is a good example.

It is the name given to a putter Jack Nicklaus used to win the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol. The putter, a Bull’s Eye brand painted white, became lost in the shuffle of clubs the Golden Bear used to win his 18 major golf championships. It ended up in the hands of Steve Nicklaus during his time at FSU, and the younger Nicklaus gave the club to Wessel when he broke his own putter while tossing it in the air after a particularly frustrating shot.

Wessel kept the club, not knowing its significance until years later.

Wessel was Steve Nicklaus’ teammate and roommate at FSU, and a special teams demon during his senior season with the Seminoles. He blocked five kicks during the 1984 season, converting three of them into touchdowns, an NCAA record.

Wessel tells the story of meeting Jack Nicklaus for the first time in 1983. The Golden Bear grabbed Wessel by the arm and pulled him into a back room and without missing a beat, asked him a question about his son, Steve.

“How are you two getting along?” Nicklaus asked.

Wessel thought it was an odd question since he and the younger Nicklaus had only been roommates for a month. “We were still on our honeymoon!” Wessel wrote.

Looking back, Wessel realized what had happened. “I realized his thought process began with caring about his kids,” Wessel wrote. “That spoke volumes about how ingrained he was in his family life.”

A quick diversion for a personal story.

Was Nicklaus devoted to his children? Most definitely. It was common to see Nicklaus at his sons’ football games and his daughter’s volleyball matches and softball games. As a sportswriter during the early 1980s at The Stuart News, I’d seen Nicklaus stalk the sidelines at football games to encourage his sons. He might have been famous, but during his kids’ games, Nicklaus reacted as most parents did.

It also was not unusual for Nicklaus' wife, Barbara, to work at the scorer’s table when her daughter, Nan, played volleyball.

The Benjamin School in North Palm Beach is where the Nicklaus children attended high school. In the early 1980s, the Buccaneers ventured to John Carroll High School in Fort Pierce. Barbara Nicklaus was at the scorer’s table, and Jack Nicklaus was in the stands to watch Nan as Benjamin prepared to play a traditionally powerful Golden Rams squad.

My boss at The Stuart News, J.T. Harris, approached Jack Nicklaus, who initially waved him away, saying, “I don’t want to talk about golf.”

Harris was prepared, however, telling Nicklaus that he wanted to talk about Nan’s progress as a volleyball player.

That did the trick. Harris got the interview, a different angle and a nice exclusive.

Wessel’s involvement in sports as a youth was helped by the friendships of his mother — and his own friend-making ability — with the sons of Miami Dolphins head coach Don Shula and his assistant Howard Schnellenberger. Wessel would help out at the Dolphins’ training camp, and that got him special time with players like quarterback Earl Morrall.

Wessel even got to meet one of Schnellenberger’s neighbors at a party, a young musician named Harry Wayne Casey. Casey was at the height of his popularity as the lead singer for KC and the Sunshine Band, but Wessel regarded him as a regular guy and even got the musician a deal on a slalom ski.

Wessel’s college playing career ended after the 1984 Citrus Bowl (a 17-17 tie with Georgia), but he stayed in athletics as an assistant coach. He worked at LSU and Notre Dame, then jumped to the pros to work for the Cincinnati Bengals and Philadelphia Eagles.

Wessel’s renewed his connection with White Fang after talking with his father, who noticed the putter and vaguely recalled Jack Nicklaus was looking for two of his famous clubs. White Fang was one of them.

In April 1983, Wessel attended Steve Nicklaus’ 40th birthday party. He told Jack Nicklaus, “I may have a club that might be yours.”

Intrigued, the six-time Masters champion wanted to see it. When he realized it was White Fang, he asked to have it back. Wessel obliged, but when Nicklaus offered to send him a set of clubs as compensation, he realized he was in the right place at the right time.

“You’re not getting off that easy,” Wessel told Nicklaus. “You get Steve, and I’ll get my Dad. Let’s go to Augusta, and we’ll call it even.”

Nicklaus agreed, and the match was on.

The book is sentimental and sweet. Chastain’s role was to fill in the gaps by speaking with some of the main characters Wessel encountered during his athletic career. Chastain, who is a fine storyteller in his own right, did the necessary research on White Fang, but steps back and allows Wessel to control the narrative.

Jack Nicklaus wrote the foreword to White Fang and the Golden Bear. He notes that Joe Wessel “had a special relationship with his dad,” adding that setting up the foursome at Augusta was “a small part in their life together” that nonetheless brought him “pure joy.”

White Fang and the Golden Bear is a brief story, but a special one. It’s a story filled with pure joy, good advice, funny stories — and some extraordinary luck.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed