www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/upper-deck-to-produce-cards-of-zamboni-driver-turned-goalie-david-ayres/

|

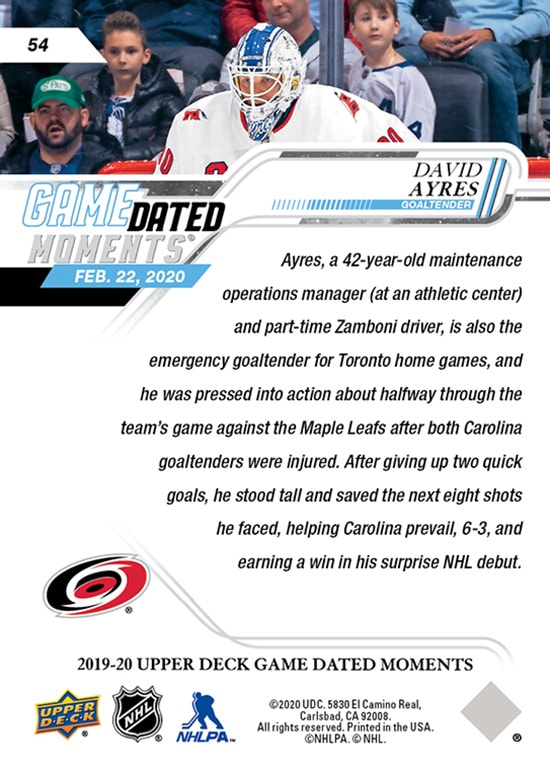

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Upper Deck producing a hockey card of David Ayres, the part-time Zamboni driver who played as an emergency goalie for the Carolina Hurricanes on Feb. 22: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/upper-deck-to-produce-cards-of-zamboni-driver-turned-goalie-david-ayres/

0 Comments

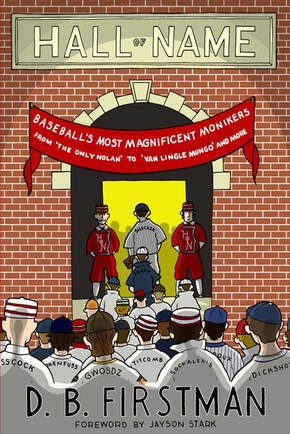

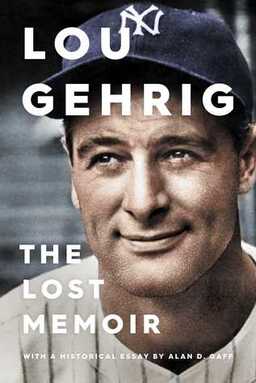

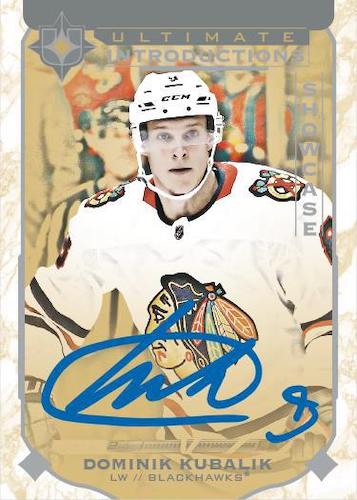

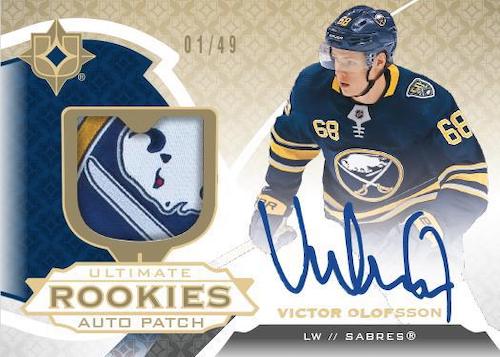

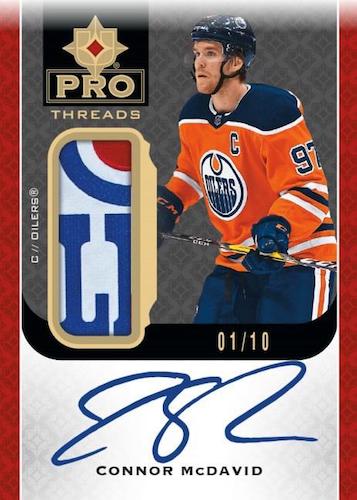

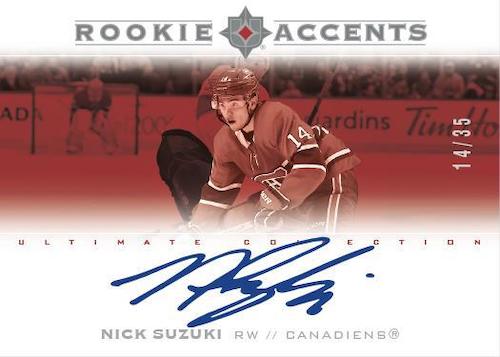

Baseball is a wonderful game, but baseball writing can be even better. Especially when the writer is engaging, informative and likes to have a good time. That is what makes D.B. Firstman’s self-published book, Hall of Name: Baseball’s Most Magnificent Monikers from ‘The Only Nolan’ to ‘Van Lingle Mungo’ and More (DB Books; paperback; $12.60; 312 pages) such a fun read. In the book, which is due out March 17, Firstman has selected 100 unique baseball names. Firstman's prose has a winking, smirking, joking tone and has a good deal of snark. But Firstman also educates the reader about players’ names that have made us laugh, snicker and even cringe. I was sold when the first player Firstman wrote about was St. Petersburg native Boof Bonser, although I was disappointed Piano Legs Hickman was not included. That doesn’t matter; Hall of Name is the kind of book where you can turn to any page and be entertained. “I’ve always been inquisitive and a lover of words,” Firstman writes. Firstman also enjoys anagrams, which are an integral part of every biography. The book is divided into four sections, with players listed alphabetically: Baseball Poets and Men of (Few Different) Letters, Dirty Names Done Dirt Cheap, Sounds Good to Me, and No Focus Group Convened. As free-wheeling as Firstman is, the book has a very consistent structure to it. Each player’s capsule includes his full birth name, the pronunciation of difficult parts (where applicable), height and weight, birth/death date, position, years active and the player’s name/etymology. After every biography, each player capsule ends with the player’s best day, “The Wonder of His Name,” not to be confused with, fun anagrams and ephemera. The final category contains fun facts and trivia about each player. Having gotten all the formalities out of the way, one can tell Firstman did some wonderful research and had a blast with the anagrams. For example, by using the full name of Josh Outman (Joshua Stephen Outman), the anagram is “Oh Jesus! A potent human.” Or, Orval Overall is “Roll over lava.” Love it. Another fun fact about Overall: His first and last names contain 11 letters, but only six of them are unique. Some of Firstman’s comments are almost better than the trivia that was dug up for the players. Gene Krapp, for example, died from cancer of the bowels (I am not making this up). Doug Gwosdz is a “competent catcher; bad Scrabble draw.” Jennings Poindexter “apparently read liquor bottles more than books.” Scarborough Green “sounds like the name of a British detective from the 1930s.” Roll some of these names off your tongue. From the first section there is Callix Crabbe, Scipio Spinks (“Now, there’s a name,” Jim Bouton wrote in Ball Four, while incorrectly misspelling his last name as “Spinx.”), Greg Legg and Ugueth Urbina (the only player in major league history with the initials UU or UUU, Firstman writes. From the second: Tony Suck, J.J. Putz, Rusty Kuntz and Johnny Dickshot. Names gracing the third section include Milton Bradley, Drungo Hazewood, Razor Shines, Biff Pocoroba, and of course, Van Lingle Mungo. And the fourth section includes Harry Colliflower, Purnal Goldy, Grover Loudermilk, Dorsey Riddlemoser, Joe Zdeb and lastly, Edward Sylvester Nolan, better known as The Only Nolan. Firstman decided to self-publish Hall of Name after being rejected by small publishers in 2012. The publishers basically said, “Privately we love the concept .. but it just won’t sell enough to be worth our while,” Firstman writes. Publicly, I believe Hall of Name will sell quite well. D.B. Firstman has produced an entertaining, funny and interesting look at baseball names. Not nicknames, for the most part (we’ll concede The Only Nolan), but real names. Yes, Pocoroba’s first name really is Biff, and Bonser had his first name legally changed to Boof in 2001. I look forward to another edition in the future; with so many baseball names out there, there has to be enough for Volume 2. I am just hoping Piano Legs Hickman makes the cut the next time.  I’ve made it a habit to read every piece of literature I can find about Lou Gehrig, and it’s been rewarding. The first sports book I ever read as a child was Paul Gallico’s 1942 book, Lou Gehrig: Pride of the “Yankees.” Since then, I’ve read books by Ray Robinson (Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time), Jonathan Eig (Luckiest Man), Dan Joseph (The Last Ride of the Iron Horse), Tony Castro (Gehrig & the Babe), John Eisenberg (The Streak), Eleanor Gehrig (My Luke and I). Those are the ones I can remember. But reading something by Gehrig himself? Now, that’s fresh. Thanks to historian Alan D. Gaff, readers can enjoy Gehrig’s story in his own voice — at least for one season. But what a season — 1927, the year of Murderers’ Row, the New York Yankees team that went wire-to-wire to dominate the American League and then swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in four straight games in the World Series. Lou Gehrig: The Lost Memoir (Simon & Schuster; hardback; $24.99; 240 pages), is a book in two parts. The first half of the book reprints (with errors and grammatical mistakes cleaned up for clarity), the columns Gehrig wrote that were printed in the Oakland Tribune beginning Aug. 18, 1927, under the title, “Following the Babe.” Makes sense, since Gehrig batted cleanup behind Babe Ruth in 1927 and hit 47 home runs, second only to the Bambino’s 60 that season. The columns were also printed in the Pittsburgh Press and Ottawa Daily Citizen, but the Oakland columns are used in Gaff’s book because it was the only complete run of the series.  Historian Alan D. Gaff. Historian Alan D. Gaff. Gaff said he found the Gehrig columns while “researching another topic,” but then leaves the reader guessing by not revealing what he was looking for when he stumbled upon the first baseman’s narratives. The second half of the book is a biographical essay about Gehrig written by Gaff, 71, an Indiana native who graduated from Indiana University in 1979 with a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in American history from Ball State University the following year. Gaff also publishes a blog, and he is looking forward to the May 12 release of Lou Gehrig: The Lost Memoir. “Reading Gehrig’s life story ninety-three years after it appeared is a real treat for baseball fans,” Gaff writes. He’s right. Gehrig, humble to a fault, was 24 in 1927 when the columns were published. Whether he wrote the columns, or whether a ghostwriter stepped in, can be debated. Perhaps it was a combination of both. Christy Walsh, who represented both Gehrig and Ruth, pitched the idea to the newspapers outside New York figuring (correctly) that the metropolitan area was already saturated with Yankees’ coverage. Publishing columns in the hinterland would generate more interest. Gehrig’s modesty shines through. “As a high school ballplayer, I was no bargain,” he writes. “As a hitter, I was a bust.” Gehrig’s admiration for Ruth is evident in his writing. “Talk all you please about (Ty) Cobb and (Tris) Speaker and the rest of the great hitters, the Babe is in a class by himself.” Gehrig also writes about the route he took to get to the Yankees, kick-started when his father became ill in 1920. He talks about bench jockeying, and how Ty Cobb would ride him mercilessly. “The tamest thing he called me was a ‘fresh busher,’ and from there he climbed upward,” Gehrig writes. However, Gehrig writes that once he became established, Cobb became “one of my best boosters.” Gehrig also counted Speaker and Eddie Collins (“he’s a wonder”) as friends and praised Walter Johnson’s sportsmanship (“he’s just about the finest and cleanest character in baseball”). He also describes his teammates, their habits and hobbies. Long before Gehrig and Ruth had a disagreement during the 1930s that led to silence between the two men, Gehrig had nothing but praise for his teammate. “He is no plaster saint, and he admits it,” Gehrig writes. “But through it all, he stands out as the greatest of the great in baseball; a wonderful all-around ballplayer and a corking fine fellow." At times, Gehrig gets a few of his facts wrong when it comes to game day events. Gehrig notes the first time he got into a box score as a hitter was when he pinch-hit against Washington and struck out against John Hollingsworth. That would have been July 2, 1923, and while Gehrig replaced Wally Pipp at first base to start the sixth inning, he did not bat until the seventh inning, when Hollingsworth struck him out. However, Gehrig’s first appearance as a hitter actually came June 18, 1923, when he pinch hit for Aaron Ward and struck out against Detroit pitcher Ken Holloway. I can’t fault Gehrig for forgetting; after all, I have the benefit of Retrosheet.org, and Lou did not. Still, Gehrig’s narrative is interesting and informative. Gehrig’s observations during the 1927 World Series are instructive and to the point. So are his conclusions. “We won by grace of superior pitching, timely hitting, and a fine defense,” Gehrig writes. “We simply won because we had more stuff than the Pirates.” The final half of the book contains Gaff’s biographical essay about Gehrig. Gaff’s bibliography contains 24 books and articles about Gehrig, and he draws from authors like Gallico, Eig, Robinson, and Yankees historians Marty Appel and Harvey Frommer. Gaff also researched 66 different newspapers for his essay. His narrative is concise and flows nicely. There are plenty of nuggets of information, the essay provides context and balances well against Gehrig’s humble, optimistic outlook about baseball and life. Gaff’s effort is a real treat for fans of Lou Gehrig, and for baseball fans in general. The Iron Horse remains a heroic and tragic figure, but Gaff’s discovery of Gehrig’s memoir from 1927 — when he was just blossoming as a power hitter and everyday star — is a valuable baseball treasure. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily, previewing Upper Deck's 2019-2020 Ultimate Collection hockey set.

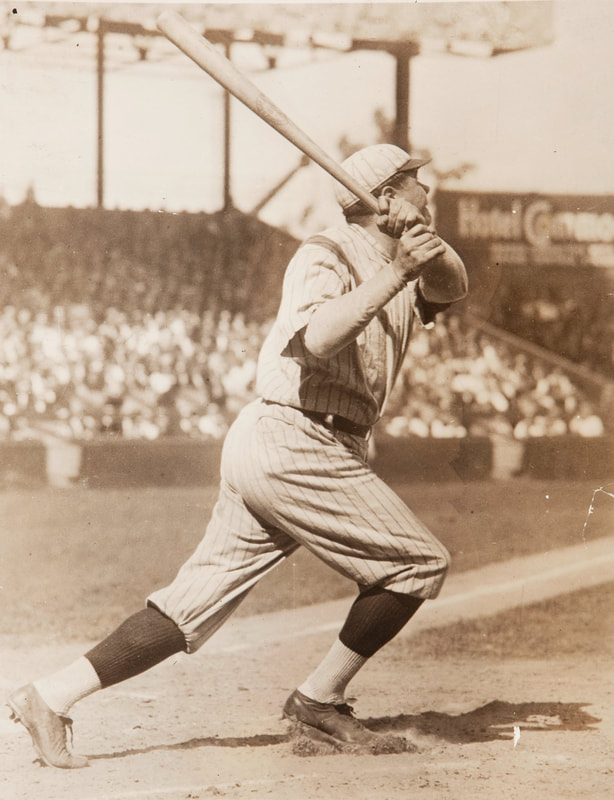

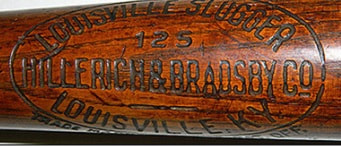

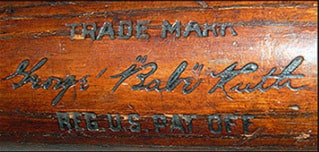

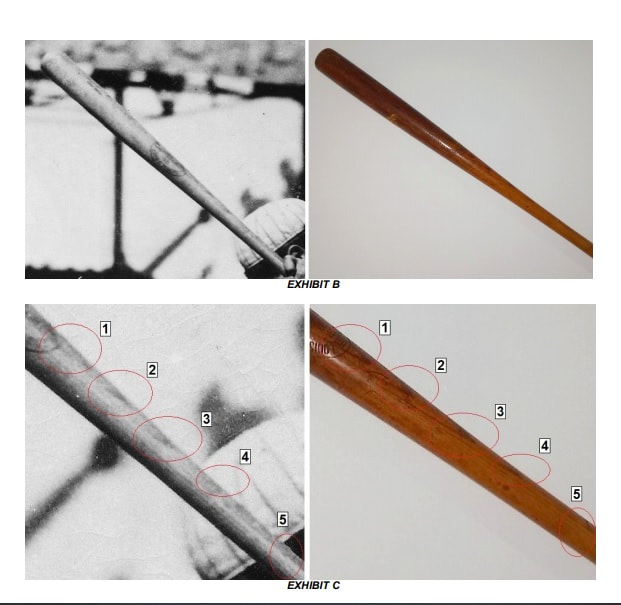

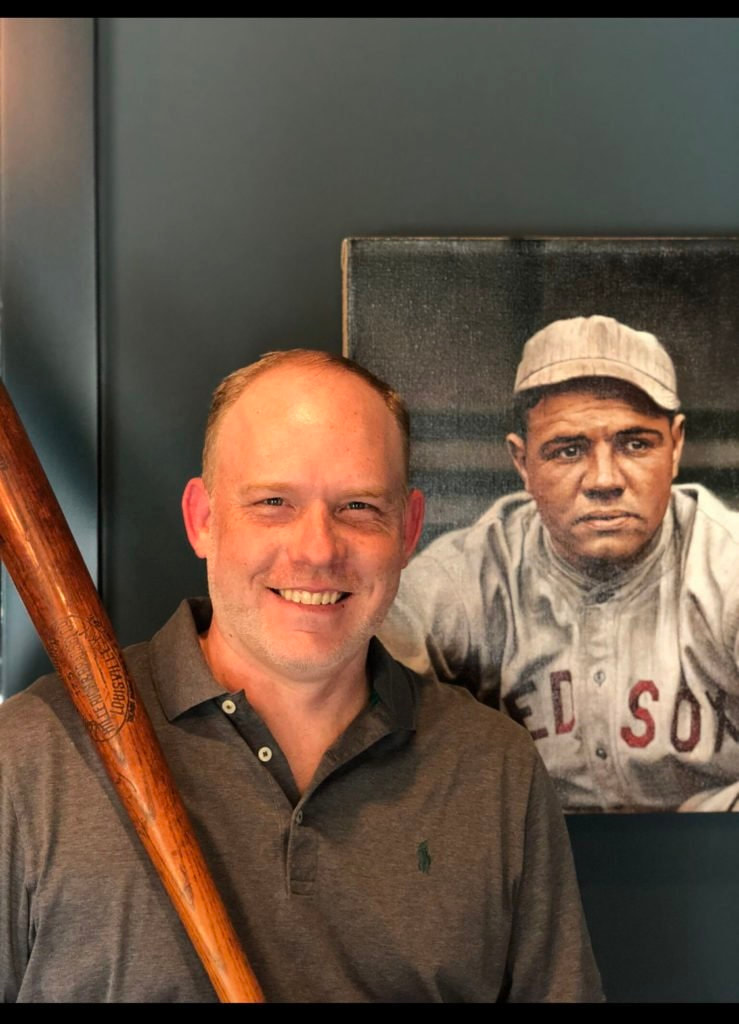

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/upper-decks-2019-2020-ultimate-collection-hockey-raises-the-bar/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Justin Cornett, who photo-matched a Babe Ruth game-used bat from 1921 to an iconic photo of the Hall of Fame slugger:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/collector-matches-babe-ruth-bat-to-famous-1921-photo-of-slugger/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily previewing the 2019-2020 Panini Court Kings basketball set:

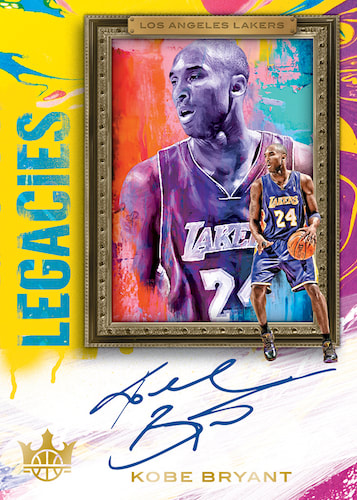

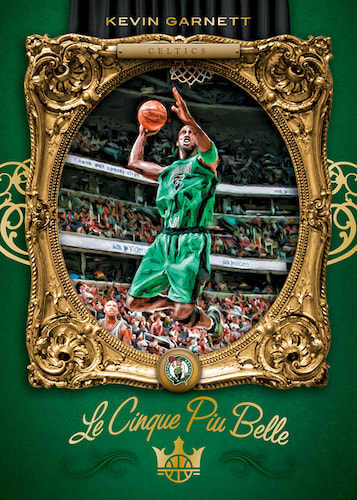

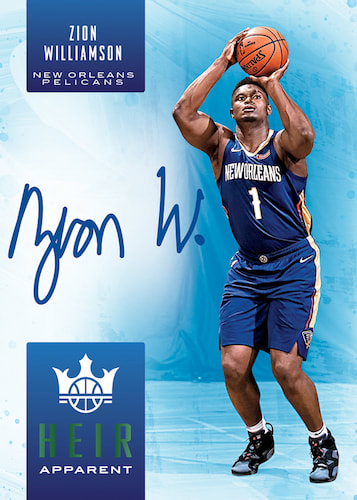

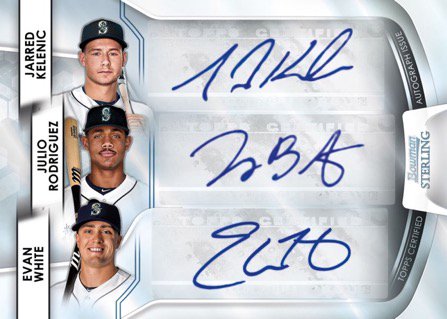

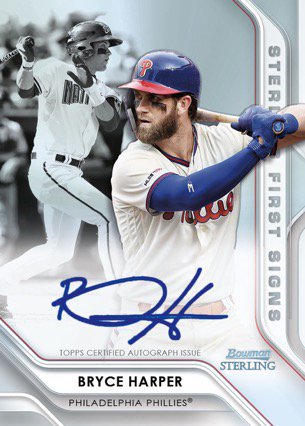

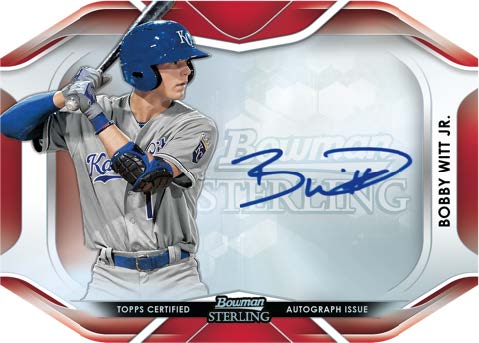

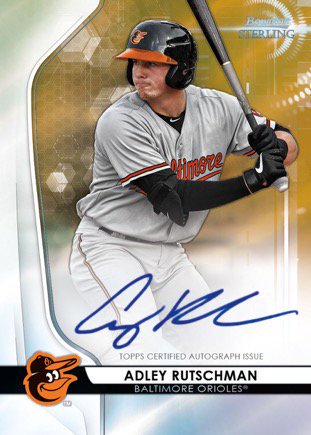

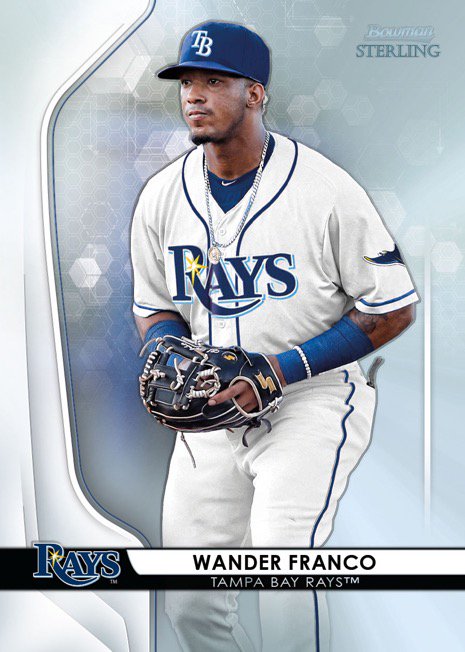

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2019-2020-panini-court-kings-brings-the-color/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily previewing the 2020 Bowman Sterling baseball set, which goes on sale in August:

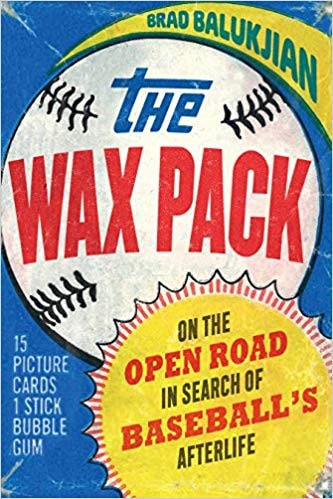

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2020-bowman-sterling-preview/ Here's a review I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about "The Wax Pack," by Brad Bulakjian. On the heels of the podcast done with NewBooksNetwork:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/waxing-nostalgic-brad-balukjians-new-book-brings-14-players-from-1986-topps-set-to-life/ Here is a podcast I did with Brad Balukjian for his upcoming book, "The Wax Pack."

newbooksnetwork.com/brad-balukjian-the-wax-pack-on-the-open-road-in-search-of-baseballs-afterlife-u-nebraska-press-2020/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Gregg Garfinkel, a California attorney who makes gifts out of baseballs:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/turning-big-league-baseballs-into-unique-products/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed