I’ve made it a habit to read every piece of literature I can find about Lou Gehrig, and it’s been rewarding.

The first sports book I ever read as a child was Paul Gallico’s 1942 book, Lou Gehrig: Pride of the “Yankees.” Since then, I’ve read books by Ray Robinson (Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time), Jonathan Eig (Luckiest Man), Dan Joseph (The Last Ride of the Iron Horse), Tony Castro (Gehrig & the Babe), John Eisenberg (The Streak), Eleanor Gehrig (My Luke and I).

Those are the ones I can remember.

But reading something by Gehrig himself? Now, that’s fresh.

Thanks to historian Alan D. Gaff, readers can enjoy Gehrig’s story in his own voice — at least for one season. But what a season — 1927, the year of Murderers’ Row, the New York Yankees team that went wire-to-wire to dominate the American League and then swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in four straight games in the World Series.

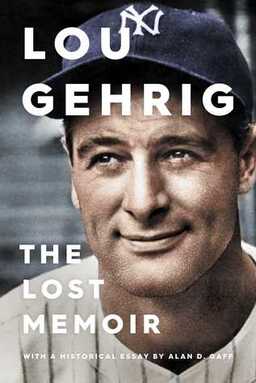

Lou Gehrig: The Lost Memoir (Simon & Schuster; hardback; $24.99; 240 pages), is a book in two parts. The first half of the book reprints (with errors and grammatical mistakes cleaned up for clarity), the columns Gehrig wrote that were printed in the Oakland Tribune beginning Aug. 18, 1927, under the title, “Following the Babe.” Makes sense, since Gehrig batted cleanup behind Babe Ruth in 1927 and hit 47 home runs, second only to the Bambino’s 60 that season.

The columns were also printed in the Pittsburgh Press and Ottawa Daily Citizen, but the Oakland columns are used in Gaff’s book because it was the only complete run of the series.

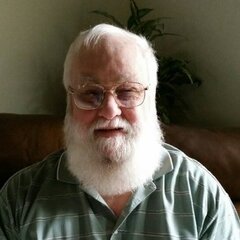

Historian Alan D. Gaff.

Historian Alan D. Gaff. The second half of the book is a biographical essay about Gehrig written by Gaff, 71, an Indiana native who graduated from Indiana University in 1979 with a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in American history from Ball State University the following year.

Gaff also publishes a blog, and he is looking forward to the May 12 release of Lou Gehrig: The Lost Memoir.

“Reading Gehrig’s life story ninety-three years after it appeared is a real treat for baseball fans,” Gaff writes.

He’s right. Gehrig, humble to a fault, was 24 in 1927 when the columns were published. Whether he wrote the columns, or whether a ghostwriter stepped in, can be debated. Perhaps it was a combination of both.

Christy Walsh, who represented both Gehrig and Ruth, pitched the idea to the newspapers outside New York figuring (correctly) that the metropolitan area was already saturated with Yankees’ coverage. Publishing columns in the hinterland would generate more interest.

Gehrig’s modesty shines through. “As a high school ballplayer, I was no bargain,” he writes. “As a hitter, I was a bust.”

Gehrig’s admiration for Ruth is evident in his writing. “Talk all you please about (Ty) Cobb and (Tris) Speaker and the rest of the great hitters, the Babe is in a class by himself.”

Gehrig also writes about the route he took to get to the Yankees, kick-started when his father became ill in 1920. He talks about bench jockeying, and how Ty Cobb would ride him mercilessly.

“The tamest thing he called me was a ‘fresh busher,’ and from there he climbed upward,” Gehrig writes.

However, Gehrig writes that once he became established, Cobb became “one of my best boosters.”

Gehrig also counted Speaker and Eddie Collins (“he’s a wonder”) as friends and praised Walter Johnson’s sportsmanship (“he’s just about the finest and cleanest character in baseball”). He also describes his teammates, their habits and hobbies.

Long before Gehrig and Ruth had a disagreement during the 1930s that led to silence between the two men, Gehrig had nothing but praise for his teammate.

“He is no plaster saint, and he admits it,” Gehrig writes. “But through it all, he stands out as the greatest of the great in baseball; a wonderful all-around ballplayer and a corking fine fellow."

At times, Gehrig gets a few of his facts wrong when it comes to game day events. Gehrig notes the first time he got into a box score as a hitter was when he pinch-hit against Washington and struck out against John Hollingsworth. That would have been July 2, 1923, and while Gehrig replaced Wally Pipp at first base to start the sixth inning, he did not bat until the seventh inning, when Hollingsworth struck him out.

However, Gehrig’s first appearance as a hitter actually came June 18, 1923, when he pinch hit for Aaron Ward and struck out against Detroit pitcher Ken Holloway.

I can’t fault Gehrig for forgetting; after all, I have the benefit of Retrosheet.org, and Lou did not.

Still, Gehrig’s narrative is interesting and informative.

Gehrig’s observations during the 1927 World Series are instructive and to the point. So are his conclusions.

“We won by grace of superior pitching, timely hitting, and a fine defense,” Gehrig writes. “We simply won because we had more stuff than the Pirates.”

The final half of the book contains Gaff’s biographical essay about Gehrig. Gaff’s bibliography contains 24 books and articles about Gehrig, and he draws from authors like Gallico, Eig, Robinson, and Yankees historians Marty Appel and Harvey Frommer. Gaff also researched 66 different newspapers for his essay.

His narrative is concise and flows nicely. There are plenty of nuggets of information, the essay provides context and balances well against Gehrig’s humble, optimistic outlook about baseball and life.

Gaff’s effort is a real treat for fans of Lou Gehrig, and for baseball fans in general. The Iron Horse remains a heroic and tragic figure, but Gaff’s discovery of Gehrig’s memoir from 1927 — when he was just blossoming as a power hitter and everyday star — is a valuable baseball treasure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed