www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/gem-mint-movie-hits-home-with-message-for-obsessive-collectors/

|

Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily, reviewing the short film "Gem Mint."

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/gem-mint-movie-hits-home-with-message-for-obsessive-collectors/

0 Comments

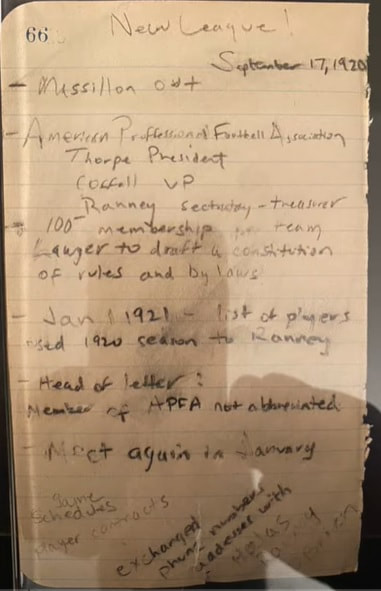

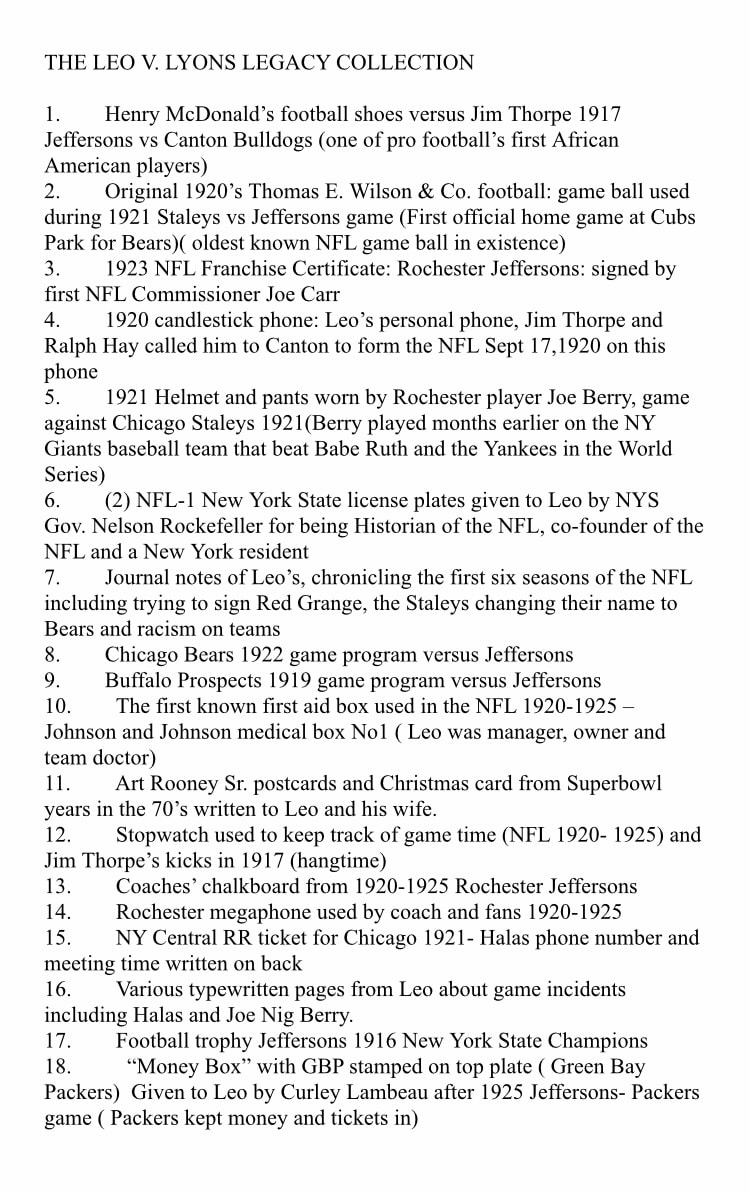

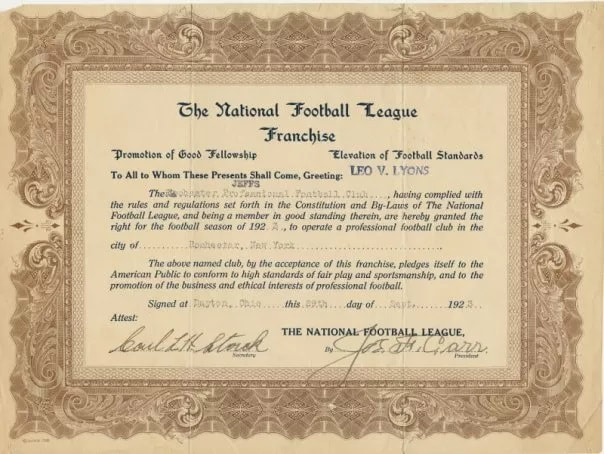

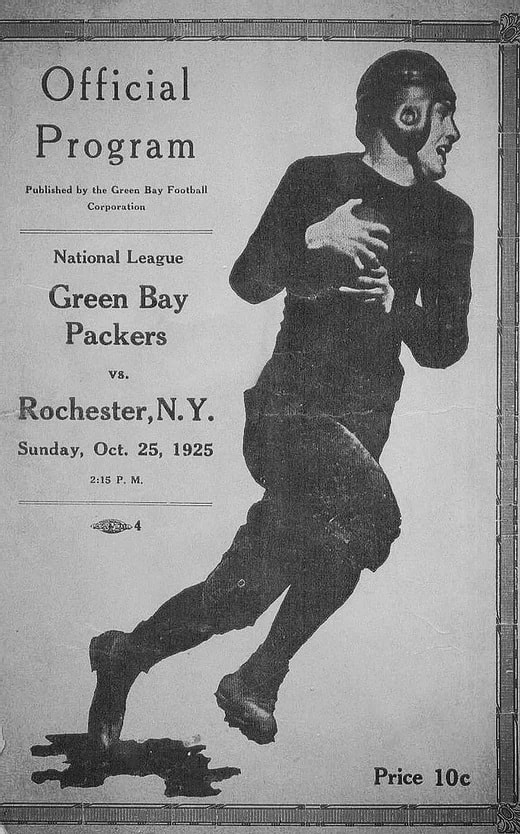

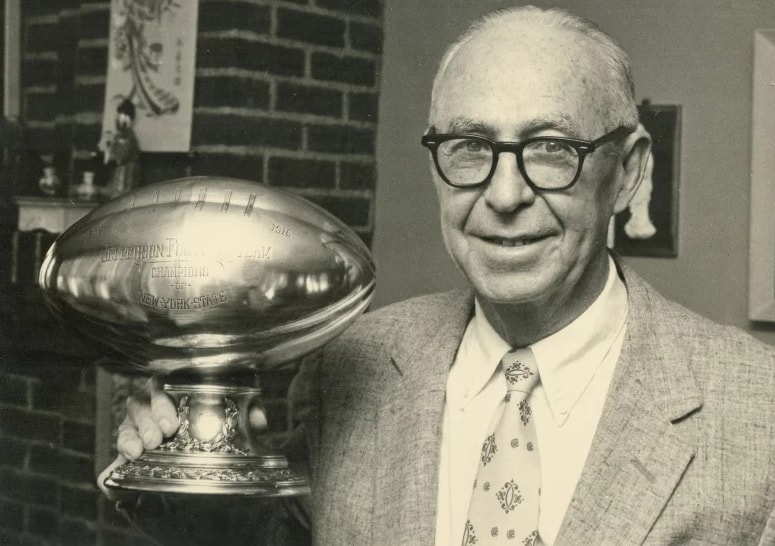

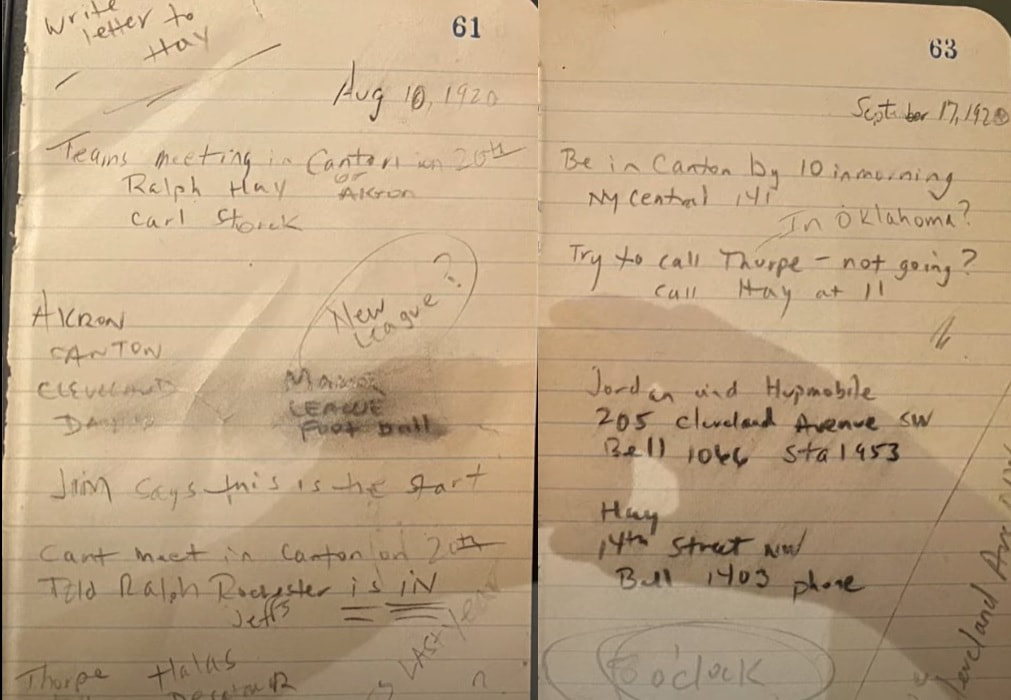

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about John Steffenhagen, whose great-grandfather, Leo Lyons, was a co-founder of the NFL. Lyons' collection included some of the notes from the meeting that led to the formation of the NFL.

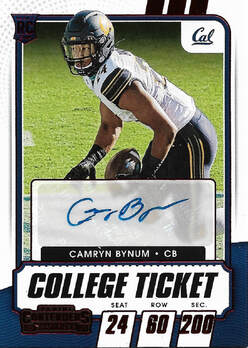

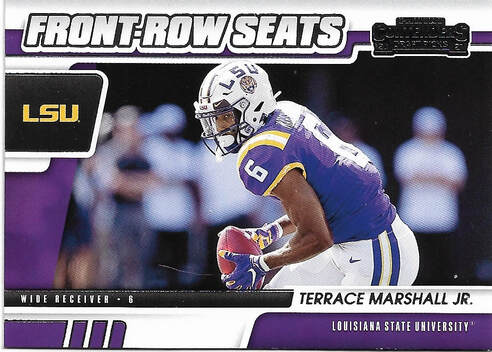

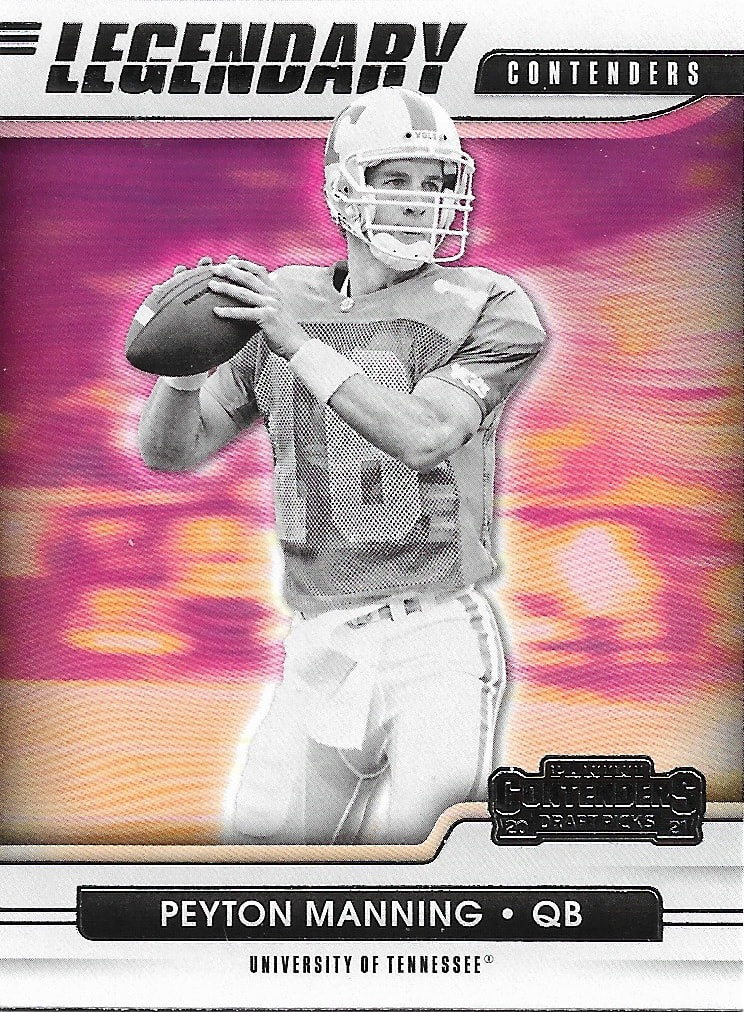

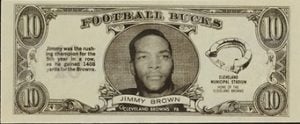

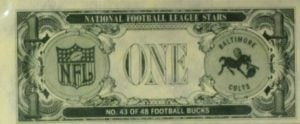

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/historic-collection-of-nfl-co-founder-leo-lyons-covers-leagues-formative  Speaking about earning a victory after a long drought, former University of Florida football coach Charley Pell once said that his team “was like a thirsty man in the desert.” I felt the same way when I went to my local Walmart and saw blaster boxes of sports cards on the shelves for the first time in months. So I grabbed a blaster box of 2021 Panini Contenders Draft Picks, since NFL minicamps are coming up soon. The Contenders product line features current draft picks, of course, but also established NFL players pictured during their college days. A blaster contains seven packs, with six cards to a pack. Pulling an autograph from a blaster is unusual, but the fates were with me as I found a College Ticket insert red parallel of Cal defensive back Camryn Byrum, who was drafted in the fourth round of the 2021 NFL draft by the Minnesota Vikings.  Doesn’t matter to me that the autograph was on a sticker, although like any collector, I prefer an on-card version. Remember: Thirsty man on a desert. That card was a nice oasis. The base set has 100 Season Ticket cards, and I pulled 35 from the box I bought. The design is clean, with a lot of foil, and, as the product name implies, has a ticket theme. The photograph on the card front shows the player in action, with the college team logo in the upper right-hand part of the picture. The player’s name and position appear across a small black banner, framed by a white border and positioned underneath his photograph. “Season Ticket” is in bold black, italic letters beneath the player’s name, with a seat, row and section randomly chosen and stamped in silver foil. There are three diagonal bars stamped in foil above the team logo, which breaks up the white border that surrounds the photograph.  The card back features a smaller, but uncropped photo of the player on the left-hand side. A UPC bar code above the photograph lends more credence to the “ticket” concept. Cute. The player’s college team logo dominates the upper-right hand side of the card and is positioned under the card’s number. The player’s name is featured in white type inside a black box, and there are 10 lines of ragged right type that provide highlights and statistics about the player’s college career. Fun stuff. In addition to the base cards and autograph, the blaster box I bought had two Game Ticket red parallels and four inserts. The Game Ticket cards featured Big Ten rivals Tom Brady (Michigan) and Ezekiel Elliott (Ohio State). The ticket “stub” is stamped in red foil. The inserts include two Legendary Contenders cards, which are part of a 20-card subset. The cards I pulled were Peyton Manning (Tennessee) and Russell Wilson (Wisconsin). Unlike the base cards, the photographs of the players in this insert set are displayed in black and white against a blurred reddish background. The Wilson card was a red parallel.  Interestingly, the type detailing the players’ careers were ragged left, a slight change from the base set. Draft Class is a 40-card insert set, and I pulled a Zach Wilson rookie card red parallel. Ragged right type on the back of this card, too. The final insert I pulled was a Front Row Seats card of Terrace Marshall. This insert also has 40 cards, but the design is horizontal on the front. Back to ragged right for the type on the back. Overall, a clean-looking set. Collectors who enjoy delving into the past of NFL stars and upcoming rookies will enjoy this concept. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1962 Topps Football Bucks insert set:

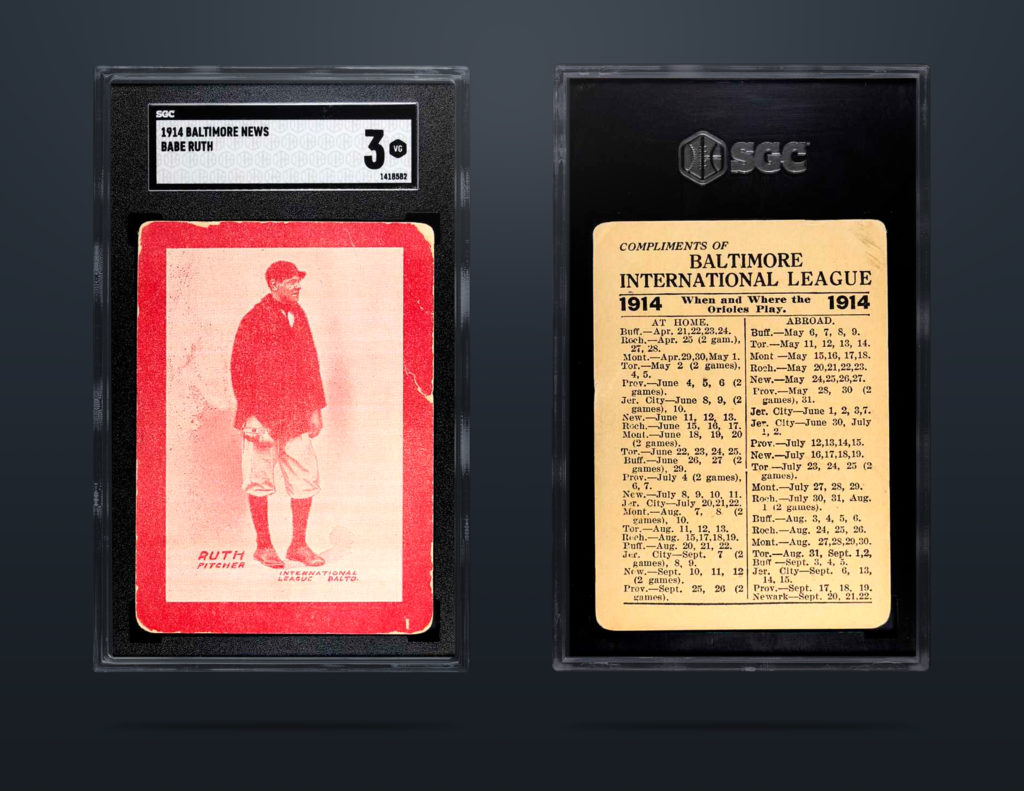

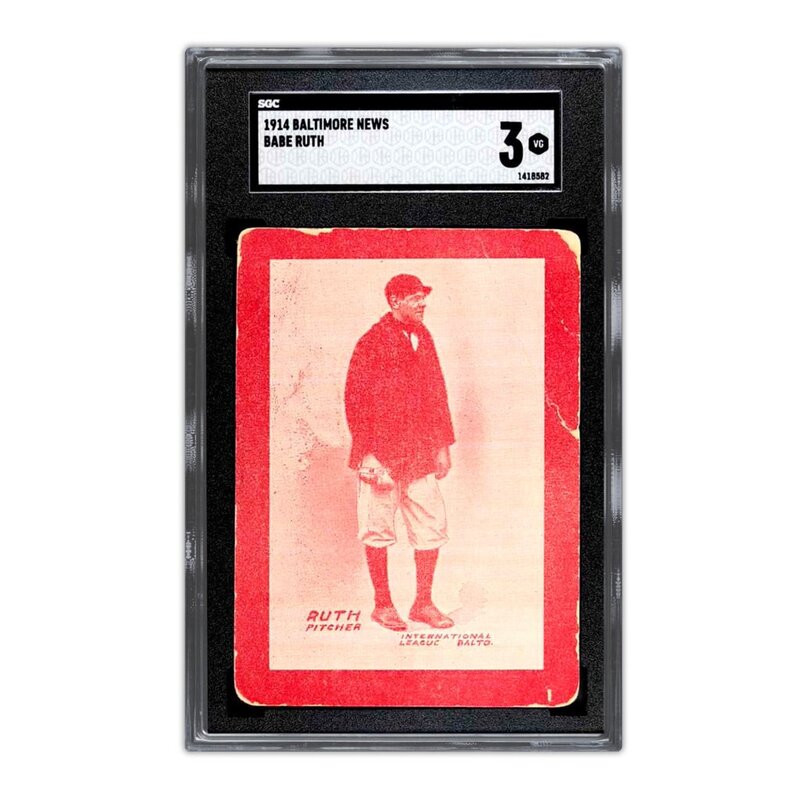

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1962-topps-football-bucks-money-in-the-bank-for-collectors/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the record-setting 1914 Baltimore News card of Babe Ruth. There is plenty of history and legal intrigue behind this card:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/record-setting-1914-baltimore-news-ruth-card-has-intriguing-back-story/

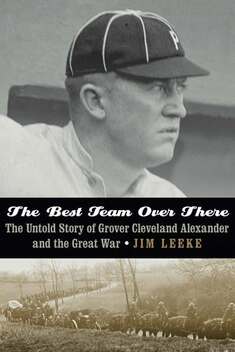

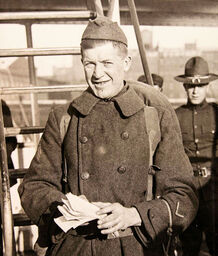

He was known as Alexander the Great, and during a seven-year stretch Grover Cleveland Alexander was one of baseball’s top pitchers.

From 1911 through 1917, only Walter Johnson won more games. Alexander had a 190-88 record and led the National League in strikeouts five times. Johnson, meanwhile, went 197-99 during that stretch and led the American League in strikeouts six times. But something happened to Alexander. He went overseas to fight during World War I, serving in France as a sergeant in the 342nd Field Artillery Regiment. He effectively missed the 1918 baseball season, appearing in three games and going 2-1. When he returned, Alexander seemed fine physically, but the war haunted him. He began drinking heavily, and his bouts with epilepsy became more of a concern but remained hidden from the public view. Alexander likely suffered from “shell shock,” which is now called post-traumatic stress disorder. Alexander would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938 but by then his life was a haze of alcoholism. In November 1950, Alexander was found dead in a hotel room in his hometown of St. Paul, Nebraska. Alexander “wasn’t the relaxed discharged soldier he appeared to be,” Jim Leeke writes in his latest book, The Best Team Over There: The Untold Story of Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Great War (University of Nebraska Press; $29.95; hardback; 247 pages). “And effects of combat jangled his nerves and his psyche.”

Alexander would win 27 games in 1920 to lead the N.L. for a sixth time. He won 181 games from 1919 through 1930 and achieved immortal status for coming out of the bullpen and striking out Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded in Game 7 of the 1926 World Series.

But he was an effective pitcher and a troubled man for most of the 1920s. Some writers believed Alexander was washed up. For example, an Aug. 18, 1921, headline in the Grenola (Kansas) Reader noted that “Alexander Nearing End of His Career.” What many people knew about Alexander came from a rather sanitized — and at times inaccurate — portrayal by Ronald Reagan in the 1952 movie, “The Winning Team.” Leeke helps add context and accuracy to the legend of Alexander, touching on the years before and after World War I but concentrating on the pitcher’s time in the military.

Leeke, an Ohio native who worked in a newspapers as a reporter, columnist and sportswriter, is no stranger to World War I history. Among his works are Ballplayers in the Great War: Newspaper Accounts of Major Leaguers in World War I Military Service (2013), which he compiled and annotated; the award-winning From the Dugouts to the Trenches: Baseball during the Great War (2017); and Nine Innings for the King in 2018.

Before the war, Alexander was nearly unstoppable. He won 28 games as a rookie in 1911 and became the only other pitcher besides Christy Mathewson to win 30 or more games in three consecutive seasons. During his career he won more than 20 game nine times and tied Mathewson for the National League record in victories with 373. “That a youth with ‘Grover Cleveland Alexander’ wished on him at birth could succeed in any line of endeavor is strange,” a June 1911 wire story began. “Most hopefuls nicked with the monacher (sic) of eminent citizens are flagged at the post.” Not Alexander. “He knows nothing that resembles fatigue; he never sulks; he is always ready,” a wire dispatch noted two months later. In 1915, Alexander led the Philadelphia Phillies to their first N.L. pennant by winning 31 games, throwing 12 shutouts, completing 36 games and posting an ERA of 1.22. Alexander led the National League in innings pitched seven times and topped 300 innings nine times. And Alexander was a favorite of fans and teammates. “Alexander is admired, he is loved by every member of his team,” St. Louis sportswriter Sid C. Keener wrote on the eve of the 1915 World Series. Men named their children after him. The Butte (Montana) Miner reported in September 1916 that Jerry Kennedy a popular cigar clerk a local saloon, named his 12-pound, firstborn son Grover Cleveland Alexander Kennedy. That’s a mouthful. A wire story in March 1917, when Alexander was holding out for $15,000, noted that “his long arm reached down in the baseball depths about eight stories and pulled a team that was chronically near the tail end up to a commanding position on the heights.” The Phillies, despite enjoying success through Alexander, traded the pitcher and catcher Bill Killefer to the Chicago Cubs two weeks before Christmas 1917, news that was “a hefty lump of coal” for Philadelphia fans. “The deal gutted the Phillies,” Leeke writes. It was a pre-emptive move by Philadelphia. Team officials believed Alexander would be drafted, so they took the money and ran. So, the Phillies took the money and ran. As it turned out, Alexander was drafted, despite originally believing he would receive a low classification because his mother was dependent upon him. “The Philadelphia-Chicago deal smells little better today,” Leeke writes.

Alexander’s drinking increased when he returned from Europe. He was also treated for a stomach condition while in France, Leeke writes, even though he said he had never been sick during his time the Army.

“The Great War put an end to my day dreaming of various records,” Alexander would say. The war certainly ruined any chance of Alexander winning 400 games. He would lead the N.L. in innings pitched seven times and topped 300 innings nine times. Leeke helps the reader understand what the men who served during World War I faced. He traces Alexander from his enlistment until he returned from Europe. Alexander received his training with the 342nd Field Artillery Regiment at Camp Funston in Kansas. The outfit was organized as “a motorized heavy-artillery outfit,” Leeke writes. Leeke draws from the regiment’s history to paint a picture of the fast-paced training Alexander and his colleagues went through. What made this regiment stand out was its athletic talent, Leeke writes. In addition to Alexander, athletes in the regiment included Clarence Mitchell of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Otis Lambeth of the Cleveland Indians, Win Noyes of the Philadelphia Athletics and Chuck Ward of the Dodgers. Football star George “Potsy” Clark, who coach the Detroit Lions to an NFL championship in 1935, also was a member of the regiment. In a nice touch, Leeke begins every chapter of The Best Team Over There with a war poem from famed sportswriter (and WWI Army lieutenant) Grantland Rice. “They were surprisingly good,” Leeke told podcaster Dean Karayanis on the “History Author Show” in April. “Not what I expected. You know, some of his sport poems are very light and casual and funny. But the war poems, by and large, were not that. “They have real emotion to them, some of them have real power to them.” The doughboys at Camp Funston, meanwhile, were suffering through training because of the Kansas prairie’s extreme seasonal changes. Soldiers found the camp “too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, and too unpredictable in between,” Leeke writes. As for Alexander, he had time for a quick wartime wedding, marrying Amy “Aimee” Marie Arrant on June 1, 1918, in Manhattan, Kansas. Alexander and his outfit shipped to Camp Mills, New York, two days later and headed overseas on June 28, Leeke writes. Leeke devotes chapters to Alexander’s unit sailing to Great Britain and then to France. The 342nd arrived in Liverpool on July 10 after what Alexander called “a splendid journey.” Four days later they arrived in France and traveled to Camp de Souge, nicknamed “The Little Sahara.” The troops had to learn how to put on gas masks immediately, and that was always a concern. Leeke writes that Alexander was soon promoted to corporal and had at least one epileptic seizure while in France. His promotion meant that he had less time to play baseball, although “the sport was wildly popular among Yanks serving in France.” Alexander would say that he pitched in five games during his time in France. Alexander and his unit finally saw action in the St. Mihiel offensive, digging in at Bouillonville. Alexander heard the shelling by the Germans and at one point watched a shell bounce past him; fortunately, it was a dud, Leeke writes. Alexander would be promoted to sergeant on Oct. 3, 1918, and became a gunner. Alexander would be praised for coolness under fire, exhibiting the same calm demeanor he had on the mound, Leeke writes. War, of course, has higher stakes, so Alexander’s men would come to appreciate his steely persona. Leeke provides plenty of detail, putting the reader into the trenches. It is unclear when Alexander became affected by PTSD, and he never discussed it directly. “But none could have been unaffected by the sights, smells, and sounds of war,” Leeke writes, “The awkward spread of dead animals, the terrifying whiff of gas, the deafening tom-tom-tom of the howitzers.” No wonder “John Barleycorn had begun tightening his grip” on Alexander, who first began drinking hard liquor in France. A decade later, Alexander “never budged” during a spring training game when some children set off fireworks in the grandstand. “He just sat there stiff as a board, teeth clenched, fist doubled over so tight his knuckles were white,” teammate Bill Hallahan recalled. Alexander’s unit remained in occupied Germany until early 1919, and Alexander finally returned to the United States that spring. After losing a 1-0 decision to Cincinnati on May 9, Alexander finished the year with a 16-11 record and a league-leading 1.72 ERA and nine shutouts. Alexander always insisted he was sober when he came into Game 7 of the 1926 World Series to fan Lazzeri to save the Cardinals’ lead. The Winning Team movie used it as its final scene, but Alexander pitched two more scoreless innings, helped when Babe Ruth was caught stealing for the final out of the game. Life was not kind to Alexander after baseball. His wife divorced him and he worked in a penny arcade and flea circus in New York’s Times Square. After making an appearance at the opening of the Hall of Fame, “the broken-down pitcher resumed his rocky road to nowhere,” Leeke writes. In November 1940 he received treatment at a Veterans Administration hospital in the Bronx. In 1944 police found him wandering around the streets of East St. Louis, Illinois, in his pajamas at 2 a.m. In May 1949 he fractured a vertebra in his neck after falling down a flight of stairs at an Albuquerque hotel. Later that year he was admitted to a Los Angeles hospital to be treated for skin cancer. Alexander’s final association with baseball game in 1950, when he visited Yankee Stadium for the final two games of the World Series, which featured the Phillies in the Fall Classic for the first time since Old Pete led his squad in 1915. He died several months later. Leeke was not writing a definitive biography about Alexander. Rather, he concentrated on the pitcher's time in the military while bookending his life before and after World War I. The research is detailed and extensive, with 24 pages of end notes and a meticulous bibliography. Leeke’s writing is straightforward and clear, and his narrative is entertaining. The Best Team Over There is a fine work of sports and military history. It gives the reader some new perspective about players who went overseas to fight during World War I, and perhaps answers some questions about why Alexander could not escape his demons after returning.

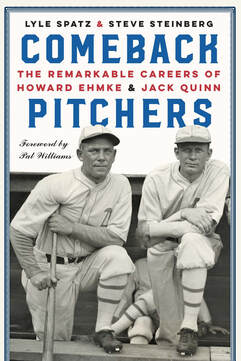

Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg are the Rodgers and Hammerstein of baseball history.

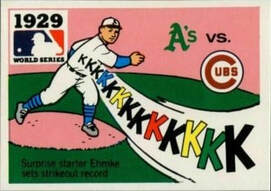

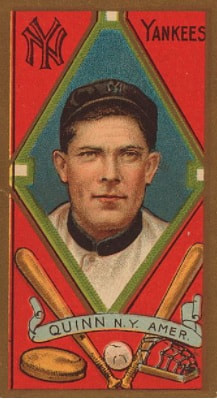

That may seem like an odd comparison, but read the collaborative efforts of Spatz and Steinberg. Their prose sings. Their latest effort is perhaps their most challenging project together, but one both baseball historians tackled with relish to produce a very interesting narrative. Comeback Pitcher: The Remarkable Careers of Howard Ehmke and Jack Quinn (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 473 pages) is a look at two pitchers whose careers spanned the deadball and lively ball eras of the 1910s and 1920s. Neither are really household names, which is interesting when one considers that Quinn won 247 games during his 23-year major league career — including a two-year stint in the Federal League. Ehmke pitched 15 seasons in the majors and had a 166-166 record. The authors note in the book’s preface that many major leaguers “are not headliners but rather men who contribute to their teams’ success while occasionally flirting with stardom.” That captures Ehmke and Quinn perfectly. Ehmke confounded the experts when he struck out a record 13 hitters as a surprise starter in Game 1 of the 1929 World Series. Quinn held the record of being the oldest pitcher to win a game, a mark that stood for nearly 80 years. Quinn was 49 years, 70 days old when, pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers on Sept. 13, 1932, he went five innings in relief to pick up 6-5 victory in the first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals. Jamie Moyer was 49 years, 141 days old on April 17, 2012 when he went seven innings as a starter for the Colorado Rockies and beat the San Diego Padres 5-3. That is, we think that is how old Quinn was. He was one of the last legal spitball pitchers before his career ended in 1933 with the Cincinnati Reds, and during his playing days he was coy about his origins — or perhaps, he simply didn’t know.

Quinn’s birthdate and place of birth “were one of baseball’s enduring mysteries,” the authors write. “He added to his enigma by his vagueness and differing stories.” The authors title their first chapter, “Jack Quinn, Man of Mystery,” and it is easy to see why. It took a family relative by marriage, after a decade of genealogical research, to finally nail down Quinn’s birthdate of July 1, 1883, in the Slovakian town of Stefurov, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The relative, Mike Scott, concluded that Quinn never told his age because “he never knew.” Quinn’s mother died shortly after the family moved to the United States, and his father worked long hours in the Pennsylvania coal mines. John Picus Quinn’s middle name was an Americanization of his father’s surname, Pajkos. The authors note that Quinn changed his last name to Quinn because there were very few Eastern European baseball players, and prejudices ran high. “Quinn” sounded like an Irish name, and baseball had plenty of Irishmen at the turn of the 20th century.

These nuggets of information are typical of a Spatz-Steinberg collaboration, and their latest work is deeply researched and has 81 pages of end notes. Their bibliography runs an additional 20 pages and includes books, magazines, websites, articles from the Society of American Baseball Research and even a 2016 letter from then-Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

Spatz and Steinberg are award-winning writers who have collaborated on two previous books: “1921: The Yankees, the Giants and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York” in 2010, and 2015’s “The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees.” Separately, Spatz has written several books, including 2011’s Dixie Walker: A Life in Baseball, Hugh Casey: The Triumphs and Tragedies of a Brooklyn Dodger, in 2017, and New York Yankees Openers: An Opening Day History of Baseball’s Most Famous Team, 1903-2017. Steinberg’s body of solo work includes Urban Shocker: Silent Hero of Baseball’s Golden Age in 2017, and The World Series in the Deadball Era in 2018. Their partnership is a smooth one, with “a true collaboration” bringing out the best in every subject they research. It is not a choppy book, where one writer’s style stands out so it is easy to determine which author wrote a particular chapter. Other than a few overlaps here and there, it is a seamless work. “As with a personal relationship, when it works well, it is rewarding and enriching,” Steinberg told SABR writer Bill Lamb in an interview. “But it takes more effort than a solo project.” Speaking of partnerships, Quinn and Ehmke were teammates for several years. Both played for the Boston Red Sox from 1923 through 1926, and for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1926 to 1930.

Throughout their careers, the authors write, both men were written off as washed up and over the hill. Quinn, who debuted for the New York Highlanders (now Yankees) in 1909, was written off as a has-been as early as 1912. And yet, he went 26-14 for the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins in 1914 and had 10 seasons with double-digit victories. He won 18 games with New York in 1910 and 18 a decade later with the Yankees. In Philadelphia he went 18-7 in 1928.

“I was as strong as an ox … and could throw pretty smart,” Quinn once said. Having a spitball in his arsenal helped, too. Quinn kept defying the odds, even when newspaper accounts noted that there were “plenty of folks in New York willing to testify that Quinn is through as a top-notcher. Quinn had the last laugh. He was durable and still pitching in semipro leagues into his 50s. Ehmke, meanwhile, also won at least 10 games 10 times during his career. He had a baffling array of pitches and windups, including a submarine delivery that seemed to come from the ground. Ehmke could also throw sidearm and overhand. He won 20 games in 1923 for a Red Sox team that only had 61 victories and followed it up with 19 in 1924 for a seventh-place Boston squad that won just 67 times. Ehmke was hailed as “the next Walter Johnson” when he played for the Detroit Tigers in 1916. Ehmke pitched six seasons in Detroit, but the friction between him and Ty Cobb in 1921 and 1922, when the Georgia Peach was the Tigers’ manager, is intriguing. Before Cobb became manager in 1921, Ehmke made it known that he wanted to be traded. “He and Cobb had not had an open breach in 1920, but both thought it best they stay apart,” the authors write. Cobb would later refer to Ehmke as “indifferent,” and intimated that he lacked courage, while the pitcher called his manager “Detroit’s greatest pennant handicap.” When Ehmke was traded to Boston and faced the Tigers in May 1923, he hit three batters, including Cobb. When Ehmke went under the stands after the game, Cobb was waiting for him, the authors write. Cobb won the fight, but Ehmke said he had more satisfaction from winning the game. “I’d still rather be the winning pitcher than the winner of the fight,” he said. Both Ehmke and Quinn found a home in Philadelphia, just as Connie Mack was returning the Athletics to prominence. The authors write that during most of the 1929 season several of Philadelphia’s top players “had little use” for the Ehmke, including Al Simmons, who reportedly exchanged punches with the pitcher. But Ehmke was 35 and wanted to pitch in a World Series, and Mack sent him to scout the Cubs during the final month of the season. That was no secret; the stunner was that Ehmke would start the series opener. “The thought was that Ehmke was scouting the Cubs for the benefit of Mack and the A’s players,” the authors write. “Little did they realize he was scouting them for himself.” The Cubs were primarily fastball hitters, and Ehmke’s “lazy motion and slow stuff” tripped them up.

Mack, appearing in a World Series for the first time since 1914 and winning a postseason game for the first time since 1913, called that Game 1 victory his greatest day in baseball.

“Ehmke had risen above the criticism and injuries he had endured those sixteen years to pitch the game of his life,” the authors write, noting that his 13 strikeouts topped the World Series record set in 1906 by Ed Walsh. When Carl Erskine struck out 14 Yankees in Game 3 of the 1953 World Series, Ehmke sent the Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher a congratulatory telegram, the authors write. Erskine had no idea he had set a record and did not know who had held it. “I’m still not sure that I can even spell that fellow’s name right,” Erskine told reporters. Ehmke would be released in May 1930. He later went on to have a successful business career producing sports tarpaulins for outdoor sports events. He remained close to Connie Mack and Philadelphia baseball events, attending old-timers’ games. He also was an enthusiastic golfer who shot in the low 80s, playing in tournaments up until a week before his death in 1959. At 46, Quinn became the oldest pitcher to start World Series game when he opened at Shibe Park in Game 4. However, he was trailing 6-0 when he left the game after facing four batters in the sixth. Fortunately for Quinn, that effort is hardly remembered, because the Athletics pulled off the biggest comeback in World Series history, scoring 10 runs in the seventh inning to win 10-8 and take a 3-1 lead in the Fall Classic. The following year Quinn became the oldest player to appear in a World Series game, pitching the final two innings of Game 3 in a 5-0 loss. He was released after the Series and was picked up by the Dodgers, where he led the National League in saves in with 13 in 1931 and nine in 1932. He got into 14 games with the Reds in 1933 before he was released, pitching his final game a week after he turned 50. While Ehmke had a comfortable retirement, Quinn scrambled to stay in baseball, pitching for semipro teams and even managing the House of David squad. However, his world was ripped apart in July 1940 when his wife Georgiana (known as Gene) tripped on a sprinkler and fell over a park bench during a family gathering. Her leg injury led to gangrene and she died two days later. “It was a blow from which he would not recover,” the authors write. Quinn began drinking heavily and died in 1946 from cirrhosis of the liver. “He drank his sorrow — to death,” a family friend said. Comeback Pitchers might be a niche read, but it is a fascinating look at two pitchers who made their mark, particularly during the free-swinging 1920s. Spatz and Steinberg lift both pitchers out of the haze and obscurity and show them for what they were — very good pitchers in an era that focused on hitters. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed