Bill Buckner collected 2,715 hits during a 22-year major-league career, but is remembered for a grounder that rolled under his legs during Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. Rookie Fred Merkle was only doing what other players did when he peeled off between first and second base after Al Bridwell’s apparent two-out, game-winning hit for the New York Giants against the Chicago Cubs in 1908. An alert Johnny Evers called for the ball, stepped on second for a force play that negated the winning run, and the game remained a tie and eventually had to be replayed. The Cubs won and went on to win the National League pennant thanks to what became known as “Merkle’s Boner.”

And then there is the case of teammates Hugh Casey and Mickey Owen. With the Brooklyn Dodgers on the verge of winning Game 4 of the 1941 World Series to even the Fall Classic, Casey struck out New York Yankees hitter Tommy Henrich for the game’s final out — but, not so fast. The ball got past Owen, Henrich reached first base safely, and the Yankees went on to win the game and eventually the Series.

Both players were maligned for the gaffe, and for years there was a question whether Casey had crossed up his catcher by throwing a spitball. Casey, out of the majors within a decade and embroiled in a paternity suit, would commit suicide in 1951 at the age of 37.

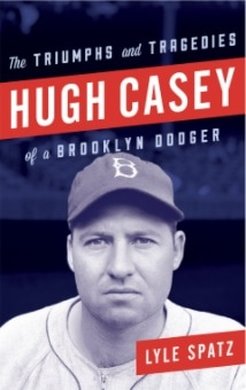

Casey’s life was more than one misguided pitch and a sad ending. Baseball author and historian Lyle Spatz presents a deeper portrait of the pitcher and the man in his latest biography, Hugh Casey: The Triumph and Tragedies of a Brooklyn Dodger (Rowman & Littlefield; hardback; 320 pages). Certainly, Casey was a colorful character, a man who redefined the role of relief pitcher during the 1940s. Unofficially, he led the National League in saves twice (saves did not become an official statistic until 1969), and was part of a raucous, swaggering, brawling Dodgers team that was led by their equally cantankerous manager, Leo Durocher.

Casey also was a complicated man who had trouble controlling his weight, enjoyed a drink more often than not, endured several separations from his wife, ran a restaurant in Brooklyn, and had a memorable impromptu boxing match in 1942 with author Ernest Hemingway during spring training in Havana.

“He was a big, boisterous guy with a cigar in one hand and a scotch in the other,” announcer Ernie Harwell recalled.

Spatz, the former chairman of the Society of American Baseball Research’s Baseball Records Committee, is no stranger to the Dodgers of the 1940s. He wrote a biography of outfielder Dixie Walker in 2011 and edited a collection of biographies for SABR called The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers in 2012. He also wrote biographies of Bill Dahlen and Willie Keeler, and collaborated with Steve Steinberg on a pair of books about the Yankees of the 1920s — 1921: The Yankees, the Giants and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York (2010); and The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees (2015).

Spatz’s talent as a researcher shines through in an extensive bibliography that includes books and articles from journals, magazines and newspapers. He taps into the baseball knowledge of historians and writers like John Thorn, Jules Tygiel, Charles Alexander, Jonathan Eig, Steven Gietschier, Peter Golenbock, Bill James, Roger Kahn and Lawrence Ritter, to name a few.

Spatz writes about Casey’s youth and minor-league career, noting that “the blood of the Old South and the Confederacy did indeed run deep” in his veins. After signing with the Detroit Tigers and playing for their minor-league clubs, Casey hooked up with his hometown Atlanta Crackers and caught the eye of manager Wilbert Robinson. It was uncertain whether “Uncle Robbie” liked Casey because of his pitching ability, Spatz writes, or because he “always knew where the fish were biting, was a Deadeye-Dick with a shotgun, and had a way with bird dogs.”

Casey would debut in the majors with the Chicago Cubs in 1935, but the team was unimpressed and shipped him back to the minors. He would emerge with Brooklyn in 1939 and would establish himself as a dependable starter and later as a lockdown reliever. But that bad pitch in the 1941 World Series turned the postseason around. Spatz writes that Durocher second-guessed himself for not going to the mound to settle his pitcher down. Owen also second-guessed himself.

“It was like a punch in the chin. You’re stunned. You don’t react,” Owen said years later. “I should have gone out to the mound and stalled around a little.

“It was more my fault than Leo’s.”

As a southerner, Casey was uncomfortable when Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947. Allegedly part of the ring of Dodgers who drafted a protest letter, Casey nevertheless worked to help Robinson field his position better; Spatz quotes historian Jules Tygiel, who wrote that Casey would hit grounders to Robinson at first base, “gently chiding” him about his fielding. But when Casey was drinking, his darker side would emerge, like the time he rubbed Robinson’s head for good luck during a card game. Robinson, miffed, continued to play cards without incident.

After a memorable performance in the 1947 World Series, Casey’s career began to go downhill the following year due to injuries and ineffectiveness. In 1949, he split his final major-league season between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Yankees, and then wound up his career in the minors.

Casey’s paternity suit is covered in detail by Spatz, who also writes about the pitcher’s tax woes with the IRS in 1951. Top that off with a separation from his wife that year, and the reasons for Casey’s suicide on July 3, 1951, seems more plausible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed