It started with Joe Jares’ 1974 book, Whatever Happened to Gorgeous George, and has continued through the years, with autobiographies by Mick Foley, Bret Hart, Chris Jericho, Ric Flair and Terry Funk, to name a few.

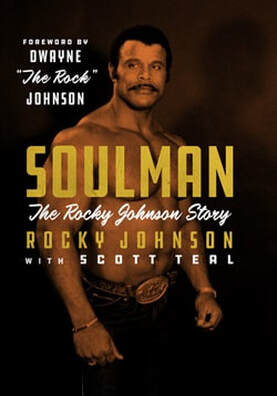

The latest in the genre comes from Rocky Johnson, a WWE Hall of Famer who starred for more than two decades. Many modern-day wrestling fans will recognize Johnson as the father of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, but Rocky Johnson was a star in his own right.

In Soulman: The Rocky Johnson Story (ECW Press; hardback; $28.95; 285 pages), Johnson and collaborator Scott Teal trace a life that had humble beginnings in Nova Scotia and blossomed into a pro wrestler who headlined cards all over North America.

Johnson is refreshingly humble as he writes about his life, giving credit for those who helped a young aspiring wrestler from Amherst, Nova Scotia, hit the big time. Teal is respected for his research and connection to pro wrestlers and an author, editor and publisher of more than 140 books. Together, they stitch together a compelling story.

Johnson, with his tight, short Afro, menacing look and sculpted body, was a fan favorite who dazzled audiences with his acrobatic moves, especially his high dropkicks. Johnson writes that he worked more than 10,000 matches over a 27-year career and was always a “babvface,” or good guy — except when he was in Japan, when he wrestled as a villain, or “heel.”

As a youth, Johnson — born Wayde Douglas Bowles in 1944 — overcame the loss of his father and the actions of an abusive stepfather, packing a cardboard suitcase and moving several hundred miles away to live with his brother in Toronto. He had holes in the bottom of one of his shoes and two dollars in his pocket.

“I know, I’m beginning to sound like all the other old people,” Johnson writes. “What’s the old story? I walked five miles to school … uphill … both ways.”

At the age of 15, Johnson began working as a helper for a delivery driver of a Toronto fish company, but he “never intended to make a career of washing cars or delivering fish.”

“They were simply a means to an end that allowed me to pursue other goals,” Johnson writes.

Johnson trained at a wrestling school in Hamilton, taking a bus from Toronto twice a week. He worked for several promotions in Canada, including in Toronto, Calgary and Nova Scotia. Johnson stood out as a black wrestler and was coveted by promoters for that reason, but he never played the race card and refused to take part in angles that perpetuated racial stereotypes. However, he did endear himself with promoters by working well with other wrestlers, taking bumps when asked and “putting over” other wrestlers.

“I never had a problem putting anyone over,” Johnson writes. “If a promoter asked me, I did it without arguing because I knew they had a reason behind it.”

Johnson shunned the backroom politics and pettiness sometimes associated with wrestlers. Was there jealousy because Johnson got shots at championship belts —and winning them — sooner than his older counterparts? Certainly. But Johnson was the kind of wrestler who brought in money, and promoters loved him for it.

Johnson’s stories are vivid, but he does not share many anecdotes about tricks and “swerves” the wrestlers played on one another. Rather, he brings the reader behind the scenes at various promotions, explaining how matches were booked and how finishes were worked out.

The reader discovers which promoters were generous (Sam Muchnick, who ran the St. Louis promotion, was “the best payoff man in the business and honest to a fault”), and which ones fought to hold back as much as they could. Johnson also reflects on the bookers, who put together the finishes for each match. He is especially complimentary toward Jerry “The King” Lawler in the Memphis territory.

Johnson also names Buddy Colt as “the best worker I ever met,” and one of the “top two or three” heels of all time. It’s hard to argue that opinion, since Colt was one of pro wrestling’s top draws until he was seriously injured when the small plane he was piloted crashed into Tampa Bay in February 1975.

“We were like salt and pepper,” Johnson writes. “When we wrestled, our match flowed like water.”

How sweet it was.

Johnson writes that none of the wrestlers could trust Bearcat Wright. In one incident, Wright made a deal to sell a truck to Johnson, but five months later, when Johnson returned to Atlanta from St. Louis, Wright had used a spare set of keys to take the truck and sell it to an elderly couple.

“When I confronted Bearcat, he just laughed,” Johnson writes.

It was later discovered that even though he seemed to have registration papers, Wright did not own the truck he sold — twice.

“I knew all along that Bearcat could not be trusted, but I never thought he was a thief,” Johnson writes. “… If anything, I’d call him a con man.”

Johnson does not call out too many wrestlers, although he accuses wrestler/booker Ole Anderson of being racist and suggests he had to babysit Tony Atlas. He spends several pages refuting some passages in Atlas’ 2010 book, Atlas: Too Much ... Too Soon, which was ghostwritten by Teal.

Johnson and Atlas made history in the WWF (now WWE), becoming the first black tag team to win that organization's world tag team title by beating the Wild Samoans.

Johnson does not get into a petty squabble with his one-time "Soul Patrol" partner and credits Atlas for trying to make amends after the book came out.

“I give Tony credit for standing up like a man and apologizing for what he had written,” Johnson writes.

Johnson does not gloss over his dalliances and affairs while on the road, and he speaks warmly of his former father-in-law, the late Peter Maivia. Quite naturally, Johnson is proud of his son, and “The Rock” certainly has made his mark in pro wrestling and in film. Father and son even found themselves together in the ring during WrestleMania 13 in 1997, when Johnson bolted into the ring to help his son.

The Rock also had the pleasure of inducting his father and maternal grandfather (Maivia) into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2008.

Many wrestlers were celebrities during the 1960s and ’70s, but Johnson writes that his son “has taken the word ‘celebrity’ to a level far, far beyond anything we experienced.”

Rocky Johnson was a celebrity in his own right, back when wrestlers conducted their business inside the ring with few gimmicks and with sweaty determination. That’s why Soulman is such a good read, because Johnson and Teal strip away the gloss and give the reader a clear view of the wrestling business.

Sometimes that view is subtle. Other times, it smacks the reader in the head like a Johnson dropkick.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed