www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/wheatlands-800-lot-auction-offers-a-little-bit-of-every-era/

|

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Wheatland Auctions Services' August sale, which runs through Aug. 4: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/wheatlands-800-lot-auction-offers-a-little-bit-of-every-era/

0 Comments

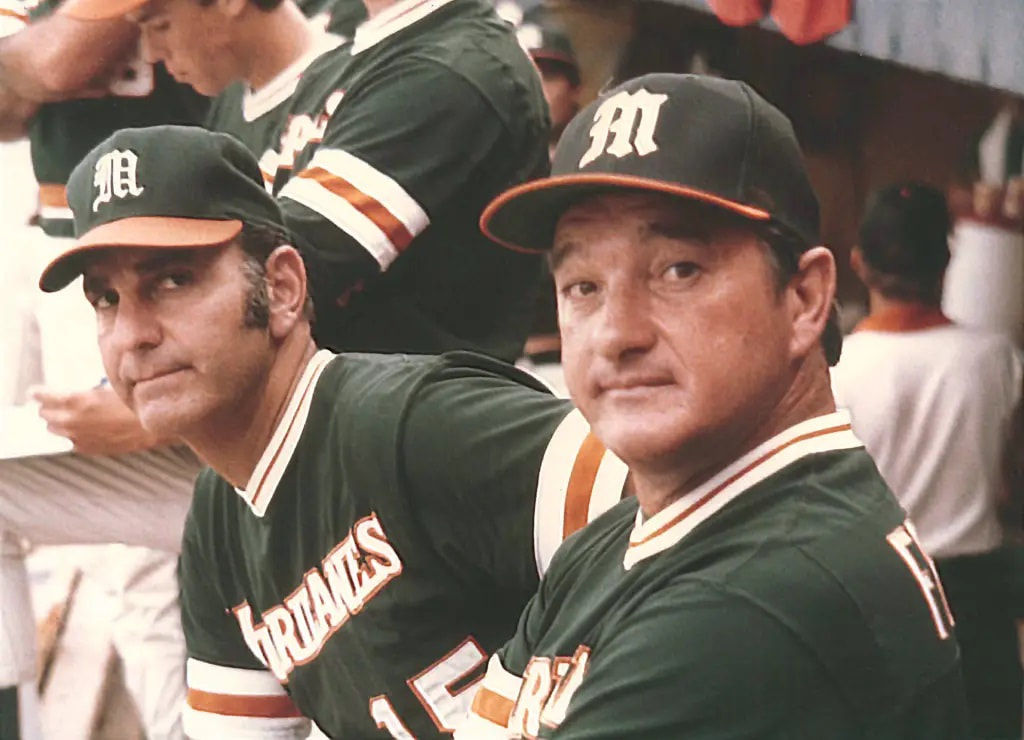

Ron Fraser was a coach worthy of his nickname.

Fraser, who guided the University of Miami to a pair of national championships and 1,271 victories during his 30-year career, impacted college baseball on and off the field. The man known as the wizard of college baseball was a showman and a marketing genius whose innovative promotions were a template for future programs. David Brauer examines the trailblazing career of Fraser in The Wizard of College Baseball: How Ron Fraser Elevated Miami and an Entire Sport to National Prominence (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 232 pages). Brauer, who grew up near the University of Illinois and is currently the commissioner of the Prospect League, met Fraser briefly during the 1992 College World Series as a youth. Twenty-five years later, Brauer was vacationing in South Florida and visited the University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame. He spoke with Earl Rubley, who was the Hall’s former president, and became intrigued after listening to stories about Fraser. Realizing that no book had ever been written about the coach, Brauer said “the wheels started turning” and he began gathering information. The Wizard of College Baseball is the result. Brauer does a thorough job of chronicling Fraser’s career and his P.T. Barnum-like mind for showcasing the sport. Fraser was the coach who helped get the College World Series on ESPN during the 1980s, giving the sport valuable exposure and boosting the sports cable network’s prestige in the process.  David Brauer (Prospect League) David Brauer (Prospect League)

There are some structure issues in the book, but they do not detract from the overall effort and may simply be my personal preference. More on that later.

Despite its location in sunny South Florida, baseball at the University of Miami was practically a wasteland when Fraser arrived at the school in 1963 after coaching the Royal Dutch national baseball team. Even Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx could not lift the program when he coached the team to a 20-20 mark in 1956-57. Fraser told USA Today in a 1989 interview that when he took the job he wanted to take a bat and ball to meet the team but the program did not own either, Brauer writes. The baseball field was in terrible shape, players wore hand-me-down uniforms from other programs and Fraser had received a mandate from the university’s athletic director “not to spend any money.” That forced Fraser to build the program from scratch, and his resourcefulness and ability to connect with donors in South Florida molded the Hurricanes into a formidable program. Not every trick worked, Brauer writes. Fraser reconditioned stained baseballs by soaking them in evaporated milk. The baseballs were white, but the smell was horrible. Other plans did not have a sour ending. Fraser introduced fall practices and home-and-home exhibitions against MLB rookie teams. He added night baseball, figuring correctly that more fans would attend games at night, rather than sitting in the broiling South Florida sun and energy-sapping humidity.

A statue of Ron Fraser stands outside Mark Light Stadium at the University of Miami. (Ken Lee photograph). A statue of Ron Fraser stands outside Mark Light Stadium at the University of Miami. (Ken Lee photograph).

He added early season tournaments and invited programs from northern schools to compete, making sure the Hurricanes played their games during the late afternoons during the round-robin events.

Fraser also introduced the Sugarcanes, batgirls who also worked the concession stands and the manual scoreboard. They also passed out promotional literature to fans, Brauer writes. Some of Fraser’s on-field innovations were viewed as radical when he introduced them. He installed artificial turf at Mark Light Stadium, which played to the Hurricanes’ strengths of pitching, speed on the bases and defense. He also relied heavily on relief pitchers to close out games; previously, starting pitchers with a lead were expected to go the difference. Fraser saw the advantage of using fresh arms late in the game to nail down victories, Brauer writes. Fraser became adept at raising money for the Miami program, offering nine-course meals on the infield at Mark Light Stadium for donors. The “Cruise to Nowhere” allowed guests to enjoy wine, dinner and entertainment aboard an ocean liner — for $125 per ticket. “He had an enormous knack for promotion,” broadcaster Roy Firestone, who worked at WTVJ and WPLG in Miami before embarking on a long career at ESPN, told Brauer. “No idea was silly to him. “Even if it started out silly, he could shape it and make it an idea.”  Ron Fraser won 1,271 games and two national titles at Miami. (University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame) Ron Fraser won 1,271 games and two national titles at Miami. (University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame)

Speaking of donors, Brauer brings the legacy of plastics magnate George Light to the forefront. Light’s donations helped fund lights and artificial turf at the Hurricanes’ field. The stadium was dedicated as Mark Light Stadium in 1978, named after Light’s adopted son, who died from muscular dystrophy in 1957.

He also raffled off car batteries and presented the Sugarcanes in bikinis for one promotion, but also worked hard to present a family-friendly atmosphere. “I was more interested in getting the people in the stands,” Fraser said. “Because I knew we’d never be really successful unless we made money.” Fraser had compassion and saw his players as family members. He reveled in their successes and grieved when tragedy struck. When one of Fraser’s former pitchers, Rob Souza, was killed in an automobile accident in January 1985, a reporter called the Miami baseball office and asked to speak to Fraser. An official in the Miami sports information department initially said that Fraser was in a meeting, but that changed when Souza was mentioned. The call was immediately put through to Fraser. “We’re all shocked down here,” Fraser told The Stuart News, his voice cracking with emotion as he called Souza a “fierce competitor” whose victory in a regional championship in 1984 sent the Hurricanes to the College World Series for the seventh time. Fraser was diplomatic but also knew how to navigate treacherous political waters. When Team USA played during the 1987 Pan American Games in Cuba, President Fidel Castro entered the stadium and wanted the Americans to come meet him. Fraser demurred, insisting that he was there to play baseball and not to meet Castro. Fraser was not going to play politics, especially given the anti-Castro sentiment in South Florida from Cuban exiles. If Castro wanted to meet Fraser’s players, he would have to make the move. Castro visited the Americans’ dugout and “politely grabbed Fraser’s arm in greeting,” Brauer wrote, noting that Fraser did not shake hands with the Cuban leader. “That was unbelievable,” Vinny Scavo, who was the team’s trainer at the Games, told Brauer. “I knew that was for Miami — all the people that struggled. He wasn’t going to let them see him go up and meet Castro. He could come to meet him.” Fraser even took a page out of Casey Stengel’s playbook, catching players who broke curfew by using a hotel employee. Fraser would hand the worker a baseball and ask the staffer to get autographs of players that wandered in late. Fraser was more subtle than Stengel, chatting up the employee and making that person a fan of the Hurricanes. The ploy worked.

The structure issue mentioned earlier was about Fraser’s personal life, which Brauer delegated as the book’s final chapter.

While Fraser was a household name among college baseball fans, a generation of fans may not have been familiar with his formative years since he died on Jan. 20, 2013. His accolades were plentiful — Fraser has been elected to eight halls of fame, including the College Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural class (2006), the Florida Sports Hall of Fame (1986), the University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame (1983) and the Florida State Athletics Sports Hall of Fame (1981). He was a four-time NCAA coach of the year, and piloted the 1992 U.S. Olympic baseball team. But how did he get there? I would have preferred that Brauer’s closing chapter, “Personal Life,” had been split, with information about Fraser’s youth until his hiring at Miami created as an earlier chapter. That would have given the reader a taste about Fraser’s path to success. His married life, anecdotes about his children and hobbies, and stories about his many friends that make up the final chapter are appropriate toward the end of the book. Just a personal preference. The only other criticisms were the misspelling of “unfazed” as “unphased,” and Brauer’s penchant for maybe using “legendary” more than necessary. That’s a career copy editor’s observation. Fraser never had a losing season at Miami and the Hurricanes appeared in 12 College World Series between 1974 and 1992, including five consecutive berths (1978-1982). Three of his teams won more than 60 games in a season, and the 1980 Hurricanes won 59 times. Fraser was eager to share his secret to success with other programs, and assistant coaches like Skip Bertman, who would lead LSU to five national championships. “I got a lot of credit as a leader because I had big crowds at LSU, and now they have big crowds everywhere,” Bertman told Brauer. “Ron was doing it ten years before me. “I wouldn’t have the success I had without Ron Fraser.” What makes The Wizard of College Baseball so insightful are the interviews Brauer conducted. He relied on newspapers, books and media guides for information, but interviews with more than 100 former players, coaches, administrators, reporters and family members give the reader a well-rounded picture of Fraser and the program he built. There is a reason there is a statue honoring Fraser outside Mark Light Stadium. He was a giant among college baseball coaches, saving Miami’s baseball program from being cut in the early 1970s. What Fraser did was contagious, and the entire Hurricanes program benefited tremendously. Brauer’s attention to detail, his anecdotal prose and insights from his interviews make The Wizard of College Baseball a success. Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an R316 Kashin Publications set coming to a Heritage Auctions sale next weekend:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/r316-kashin-publications-complete-set-from-1929-part-of-heritage-auctions-sale/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the cards and career of Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts. On July 5, he pitched his 28th consecutive complete game, an amazing stat that seems impossible today because of pitch counts and managers with quick hooks:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/robin-roberts-baseball-cards-chronicle/

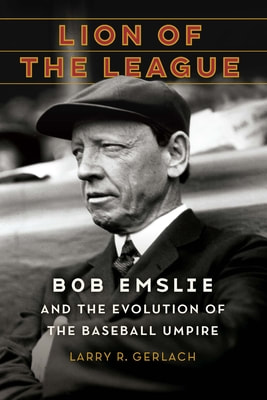

Author Larry Gerlach calls Bob Emslie “the least-known famous umpire in baseball.”

Umpires are supposed to be anonymous. They are like offensive linemen in football. They only get noticed when they make a bad play, or in an umpire’s case, a bad call. As Mitch Miller’s 1951 song “The Umpire” notes, “We ain’t got no use for the umpire unless he calls them our way.” Major leaguers Tommy Henrich, Ralph Branca, Phil Rizzuto and Roy Campanella have lines in the tune, sung by Miller and the Sandpipers. Only 10 umpires have been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Starting with Bill Klem and Tommy Connolly in 1953, nine arbiters were selected by the Veterans Committee. The last umpire chosen was Hank O’Day, selected by the Pre-Integration Era Committee in 2013. That dovetails nicely with Emslie, who was O’Day’s contemporary and a good friend. In Lion of the League: Bob Emslie and the Evolution of the Baseball Umpire (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 432 pages) Gerlach examines Emslie’s life and umpiring career during the late 19th century and early 20th century. It was a rough-and-tumble era for the men in blue; the four-man crew was still a pipedream as each game had only one umpire, and later, two. That meant that players could take liberties, by cutting corners on the basepaths, trapping the ball in the outfield and other ploys that gave teams an edge. It was difficult for an umpire to call balls and strikes and then hustle down the basepaths to decide plays on the bases. Umpires were also subjected to more verbal — and in some cases, physical — abuse from players. Unlike today’s thin-skinned, quick-trigger umpires, Emslie was reluctant to eject a player who was “kicking.” And there were plenty of reasons, as ballplayers — particularly in the 1890s—used profanity freely. According to Retrosheet.org, Emslie ejected 163 players and managers during his 35-year career.  Larry Gerlach. Larry Gerlach.

Judging from Gerlach’s strong research, Emslie was one of the game’s best. Even though he was respected by most players and manager for his fairness and evenhandedness in running a game, Emslie never got to work a World Series.

His knowledge of the rules made him a “go-to” official for major league executives, and while he was criticized late in his career for his work behind the plate — New York Giants manager John McGraw, a frequent nemesis, called him “Blind Bob” — Emslie’s work on the bases was beyond reproach. Gerlach is qualified to write about Emslie. Now in his 80s, the native of Lincoln, Nebraska received his bachelor’s degree in education and his master’s in history from the University of Nebraska. He earned his doctorate in history from Rutgers University and began teaching at the University of Utah in 1968. Since his retirement in 2013, Gerlach has been a professor emeritus of history at Utah. A former board president for the Society of American Baseball Research, Gerlach wrote the 1994 book, Men in Blue: Conversations with Umpires. He is also the coeditor of The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring. In May, he was one of three recipients of the Henry Chadwick Award, presented annually by SABR to honor baseball’s great historians, statisticians, archivists and annalists. So sure, Gerlach is qualified to write about baseball history, but why choose Emslie? Gerlach admits in his prologue that he had no intention of writing a biography about the umpire. But he made a 20-miunte speech about Emslie during a Canadian baseball history symposium. Gerlach then realized that a biography about Emslie and the era when he umpired would provide a valuable addition to baseball literature. Readers will be educated through Gerlach’s careful research and casual narrative about Emslie — he calls him “Bob” more often than not, a device that personalizes what until now has been an obscure baseball figure. And Gerlach’s research also shows readers what umpires faced during the pre-1900 era. It was not an easy time. Gerlach draws from publications from the late 1880s, like Sporting Life and the Spalding Guide, newspaper articles and even Emslie’s memoirs.

Emslie began his career as a right-handed curveball specialist. Playing in the from 1883 to 1885, American Association, he fashioned a 44-44 record in three seasons. That mark is deceptive since a sore arm ended his career. But in 1884, Emslie put together a 32-17 record with a 2.75 ERA for the Baltimore Orioles. More impressively, he started and completed 50 games that season and pitched in 455.1 innings. But the toll on his arm resulted in a rough 3-10 record in Baltimore the following season before he was released and finished his career in Philadelphia, going 0-4 with the Athletics. Still enamored with the game, Emslie turned to umpiring, coming out of the stands on Dominion Day in 1887 to help out when the regular umpire did not show up. He would work his way through the minor leagues before landing in the American Association in 1890. His first game as a major league umpire was April 17, 1890, and his career as an umpire lasted until Sept. 28, 1924, when he worked the bases for a game in St. Louis between the Cardinals and the Cincinnati Reds. When Emslie began umpiring, Gerlach writes, “it was the best and worst of times for umpires.” But as it turned out, he was “a born umpire.” His “tactful, conciliatory approach” to defusing controversy was admired by players, managers and fans — although there were times when his decisions did not sit well with them. But that is an umpire’s life. Emslie called four no-hitters during his career and worked the bases in four others. With Klem behind the plate, he was part of the fastest nine-inning game in MLB history — a 51-minute sprint at the Polo Grounds between the Giants and Philadelphia Phillies in the first game of a doubleheader on Sept 28, 1919.

He was umpiring the bases on Sept. 23, 1908, in the famous “Merkle’s Boner” game, also at the Polo Grounds. Emslie had to duck to avoid Al Bridwell’s apparent game-winning hit to center field, but when Fred Merkle failed to touch second base, Chicago Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers called for the ball.

t most likely was not the game ball, as fans swarmed onto the field, but Evers caught “a” baseball and stepped on second base, claiming the winning run was nullified by the force play. Emslie appealed to O’Day, the plate umpire, who called Merkle out. The game was eventually called a tie and was replayed at the end of the season when both teams finished with 98-55 records. The Cubs would win the rematch and the Giants were furious. In addition to “Blind Bob” affixed by McGraw after that controversial, Emslie was also known as “Wig” because of his receding hairline and his penchant for wearing a toupee, according to some sources. Gerlach disputes that despite the “execrable rowdiness of the 1890s,” there was no evidence that Emslie had that nickname. However, players did make mention of his lack of hair, with Jack Doyle taunting him in an 1897 game by suggesting he “get a hairpiece.” Doyle took it a step further in 1898, Gerlach writes. Angered by being called out, the player grabbed the umpire’s toupee and took off running. Doyle later said his $20 fine “was worth the laughs.” Emslie’s duties behind the plate diminished beginning in 1909, and he constantly lived in fear of being forcibly sent into retirement thereafter because of criticism over his farsightedness. At times during the 1910s, he was part of a team of replacement umpires. And yet Emslie persevered, becoming the “Dean of Umpires.” After retiring from active duty, he became chief of umpires and continued to be the game’s expert on rules. By the time Emslie retired, he had set records for most seasons (35) and regular-season games (4,231) as an umpire. Klem, who was an umpire for 37 years, topped that mark with 5,375 games, a mark that stood for 80 years until Joe West finished his career in 2001 with 5,640 regular-season games across 43 seasons. Gerlach concedes that trying to “capture the private person” was difficult with Emslie, outside of his love for baseball, trapshooting (of which he was an expert) and curling. Very little was known about his family life after he got married, but Gerlach has extensive information about Emslie’s formative years. Years after his death in 1943, Emslie was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1986. A baseball field in St. Thomas, Ontario, is named in his honor. It would be another decade before an umpire would be elected to the Hall of Fame. Gerlach makes a case for Emslie’s enshrinement but conceded that his lack of postseason umpiring and a refusal to wear glasses to cure his farsightedness worked against him. Umpires did not wear glasses until 1956, when Ed Rommel and Frank Umont became the first. In Lion of the League, Gerlach writes ’em like he sees ’em. It’s a fascinating view of an often overlooked — but extremely important — part of the game. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Panini America's Caitlin Clark Collection of cards that was released on July 1:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2024-panini-caitlin-clark-collection/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about some of the memorable Topps cards of Orlando Cepeda, who died on June 28:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/orlando-cepeda-remembering-the-baby-bull-in-baseball-cards/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1984 Topps baseball set -- it's 40 years old!

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1984-topps-baseball-one-big-rookie-was-highlight-of-pleasant-looking-set/

Here is an interview I did with WLKF Radio in Lakeland about Forest Ferguson on D-Day, his athletic career and life. Starting at the 6:40 mark.

If ever there was a saint in baseball, it was the late Vin Scully.

That is not blasphemy, although Scully might have objected. He was the voice of the Dodgers for 67 seasons, beginning in Brooklyn during the 1950 season and moving west when the franchise relocated to Los Angeles in 1958 and remaining on the microphone through the 2016 season. He was a devoted Catholic, a family man and a wonderful storyteller. A humble man who treated everyone with dignity, from sportswriters and fellow broadcasters to everyday fans who wandered up to the press box to say hello. Scully was also the best to call a game from behind the microphone. Hands down. Perfect Eloquence: An Appreciation of Vin Scully (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $34.95; 288 pages), is a compilation of essays that capture the soul of the man. There were plenty of tributes when Scully died on Aug. 2, 2022, at the age of 94. This book, edited by Southern California-based journalist Tom Hoffarth, is not a biography or a tribute. It is what the title implies — an appreciation of a broadcaster who touched so many lives on and off the field. “I’ve always needed you more than you’ve ever needed me,” Scully said when he signed off for the final time in 2016. That was not false modesty, but we can all agree that Scully was dead wrong on that comment. Scully called football games and golf tournaments, but it was baseball where he made his mark. He was a celebrity, but a humble one — which is difficult when you have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.  Vin Scully (Jean Fruth/National Baseball Hall of Fame) Vin Scully (Jean Fruth/National Baseball Hall of Fame)

There have been books written about Scully during his lifetime. Vin Scully: I Saw it on the Radio, a tribute by Rich Wolfe, was written in 2003. Scully is heavily referenced in Curt Smith’s 1995 book, The Storytellers: From Mel Allen to Bob Costas: Sixty Years of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth. Then he gets the full biographical treatment for the first time in Smith’s 2009 work, Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story.

The Los Angeles Times also published a commemorative book in 2022, The Voice: Vin Scully is Dodgers Baseball, along with Vin Scully: The Voice of Dodger Baseball by the Los Angeles Daily News that same year. Hoffarth’s book is much more personal. Fittingly, it is broken down into nine chapters that are called “innings.” There are observations by broadcasters like Bob Costas, Al Michaels, Joe Buck, Joe Davis, Jaime Jarrin, Ross Porter, Bob Miller and Jessica Mendoza; former players like Orel Hershiser, Eric Karros and Steve Garvey; sports journalists; baseball executives; umpires; and fans. Even Kevin Fagan, the “Drabble” comic strip artist, weighed in. The title of the Hoffarth’s book comes from the name of a seminar Scully took while attending Fordham University, the longtime journalist said in an interview with KTTV in Los Angeles. The class explained how to be “an orator who has compassion, and you’re not part of the story, you’re the one who is explaining the story to everyone else and not be the focus of it.” The beauty of Scully’s announcing technique was that he knew when to keep quiet after a big play. He would let his audience soak in the moment after he documented it. That was apparent in some of his greatest calls. Here are three that top my list. Starting with Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, when Kirk Gibson hit a 3-2 pitch off Dennis Eckersley to give the Dodgers a 5-4, come-from behind victory. “High fly ball into right field. She is gone,” Scully said, drawing out the word “is.” After more than a minute (about 68 seconds) to allow the Dodger Stadium crowd’s cheers to take center stage, Scully continued, adding that “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.” What Scully said, University of Southern California journalism professor Dan Durbin writes in an essay in Hoffarth’s book, “was take a moment of your life, a moment of baseball, and transcend it with words.” “He didn’t simply describe that moment; he recreated it into something lasting,” Durbin wrote. “He infused it with a rhetorical art.”

When Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record in April 1974, Scully’s measured and heartfelt call was memorable.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” Scully said. “A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron.”

When Sandy Koufax threw a perfect game against the Chicago Cubs on Sept. 1, 1965, it was Scully’s attention to detail that ramped up the drama in the Dodgers’ 1-0 victory.

He described how Koufax “mops his forehead, runs his left index finger along his forehead, wipes it off on his left pants leg, all the while (Harvey) Kuenn just waiting.” When Kuenn struck out for the game’s final out, Scully waited 38 seconds before brilliantly giving a time stamp to summarize the event. “On the scoreboard in right field it is 9:46 p.m. in the City of the Angels, Los Angeles, California,” Scully said. “And a crowd of 29,139 just sitting in to see the only pitcher in baseball history to hurl four no-hit, no-run games.” There are other calls, too — like the game-ending scene in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series, when Mookie Wilson’s grounder eluded Bill Buckner; or Don Larsen’s perfect game in Game 5 of the 1956 Fall Classic. And many more.

What set Scully apart from other broadcasters — besides his wealth of baseball knowledge, storytelling ability and urbane delivery — was the common touch. In his essay, sports journalist Steve Dilbeck wrote that Scully had “an unforced presence.”

He knew the names of the elevator operator at Dodger Stadium, along with the press box attendant. He would write notes — handwritten thank you notes, words of encouragement to someone who was ill. Dilbeck wrote that in 2016, Scully called Associated Press stringer Joe Resnick, who had terminal colon cancer, to offer words of encouragement. The gesture was warmly received by Resnick, who would die soon after the call. I had two encounters with Scully at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida. The first came during spring training in 1980, my first year as a sportswriter at The Stuart News. I ran into a former college classmate and fellow sportswriter, who was working at The Palm Beach Post. We were there to do some features but had never been to Holman Stadium. We believed it was rather odd that there was a metal ladder leading to the back of the press box. We climbed it and sat in what we thought was a rather cramped space. Then the sliding glass door to our right opened, and Scully said hello. “Are you writers?” he asked. We nodded. “First time here?” he continued. We nodded again. “Ah, I see, well the writers sit down there,” he motioned, pointing out several rows of seats that became embarrassingly obvious to us neophytes, as we realized we were sitting in another broadcaster’s booth. Scully was nice about it, though, telling us that “it happened a lot,” although I am sure he was being diplomatic. Two years later I saw him again, along with a group of sportswriters and players around the batting cages at the stadium before a spring game. Scully began telling stories, and everyone gathered around in a circle to listen — mesmerized. His rapport with fans was genuine. Former Dodgers executive Brent Shyer wrote that a fan stopped Scully on a Chicago street and asked for an autograph. When the fan mentioned that he had been listening to Scully for years, the broadcaster responded, “Oh, you should get a medal.” The 80th anniversary of D-Day has just passed, and Scully annually made it a point to give his listeners a history lesson on June 6. Author J.D. Salinger was there. So was John “Mad Jack” Churchill, who used a longbow, broadsword and a bagpipe while capturing more than 40 officers. He was a patriotic man, and his call when Rick Monday thwarted two people who attempted to light an American flag during an April 25, 1976, game at Dodger Stadium. “And Scully took our breath away,” Hoffarth writes.

Scully would tell a group in Pasadena during a speakers series event in 2017 that he would no longer watch NFL games because he believed players kneeling during the national anthem were being disrespectful. “I am so disappointed,” he said. “But I have overwhelming respect and admiration for anyone who puts on a uniform and goes to war. “So the only thing I can do in my little way is not to preach. I will never watch another NFL game.” Scully listened to the opposing viewpoints but remained firm in his convictions, Hoffarth writes. Scully could be disarming. Michael Green, history professor at UNLV, wrote that he was 9 years old when he met Scully in August 1974 after his parents wrote him a letter, describing their son’s desire to become a baseball broadcaster. Green entered the booth and Scully greeted him: “So you’re the guy who wants my job!” That would be a tough act to follow. Scully ad-libbed “about 80% of his lines” for his role in the 1999 movie, For Love of the Game. “As an actor, call him “The Natural,” Hoffarth writes.  Vin Scully and Tom Hoffarth (Tom Hoffarth/X.com) Vin Scully and Tom Hoffarth (Tom Hoffarth/X.com)

Scully encouraged being natural. Ask Lisa Nehus Saxon, who faced obstacles as a beat reporter for the Los Angeles Daily News when she battled to get equal access in MLB clubhouses during the 1980s. When she told Scully the next day that all she wanted was to “be one of the guys who could walk into a clubhouse without causing a stir,” the broadcaster gave some sage advice.

“Just strive to be the best version of yourself,” Scully said. That philosophy led to the Dodger Stadium press box being named in his honor in 2016. The street leading to Dodger Stadium’s main gate was named for Scully in 2016, the same year he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. Years ago, a friend gave me a tape of Scully calling a 1957 game at Ebbets Field between the Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. Listening to it, Scully’s call could have been from any of his 67 memorable seasons with the Dodgers. It was always time for Dodger baseball. It reminded me of one of my favorite Scully lines. “Andre Dawson has a bruised knee and is listed as day-to-day,” he told the audience, pausing before saying, “Aren’t we all?” That is perspective at its purest form. Hoffarth offers some wonderful perspective in a fine collection of essays. Baseball announcers can connect with their audiences in different ways. Jack Buck had that gravelly voice. Harry Caray was the boisterous, unabashed rooter for the home team. Jon Miller, Bob Uecker, Lindsey Nelson, Phil Rizzuto — along with Red Barber, Mel Allen, Ernie Harwell, Bob Prince and others — all had distinctive styles of calling baseball game. Vin Scully defined what it meant to call a baseball game. And it is appreciated. “He was baseball at its best,” former MLB commissioner Bud Selig wrote. “You can’t do any better.”  Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz are the Rodgers and Hammerstein of baseball book collaborators. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II was the lyricist-composing team who produced music for Oklahoma!, The Sound of Music, The King and I and South Pacific. All were theatrical classics. Comparing Spatz and Steinberg as a writing team to those theatrical greats may seem like a stretch, but it is totally appropriate. That is because their latest collaboration examines the life of a baseball player whose turbulent career on the diamond was equally fascinating on the stage and on film. Mike Donlin: A Rough and Rowdy Life from New York Baseball Idol to Stage and Screen (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 368 pages) showcases the authors’ thorough research and flowing prose. It sings. Both authors are familiar with the New York baseball scene and have collaborated on two previous books on the subject: 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York in 2010; and 2015’s The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the Yankees. In 2021, the pair collaborated on Comeback Pitchrs: The Remarkable Careers of Howard Ehmke and Jack Quinn. Both men are also prolific solo authors.  Steve Steinberg Steve Steinberg What makes the partnership interesting is that they live in different corners of the country. Steinberg is from Seattle, and the Brooklyn-born Spatz resides in South Florida. As Steinberg noted in an interview on his website about their collaboration on 1921, the two men approached their work by having “a real collaboration, a synthesis rather than just dividing up the book into what would be Lyle and Steve sections." It's true. It is difficult to determine which writer penned a certain passage. And that is the beauty of collaboration. Donlin is an interesting character to tackle. “Turkey Mike” — a sobriquet the player disliked — had a 12-season career that spanned 15 years (1899 to 1914). Donlin, a left-hander who also batted left-handed, hit over .300 in all but three of his seasons in the majors. He never led the league in batting; his .356 average in 1905 was behind Cy Seymour’s .377 mark, and Donlin finished second to Honus Wagner in 1904 (.329 to .349) and again in 1908 (.334 to .354). Donlin did lead the National League in runs scored (124) in 1905. The Giants of the first decade of the 1900s were dominated by two personalities — manager John McGraw and pitcher Christy Mathewson. Both are Hall of Famers, but had Donlin kept his focus and his temper in check, he might have been considered Cooperstown material. He was certainly a well-known figure among baseball fans and helped New York win back-to-back National League pennants in 1904 and 1905. He was also a key component of the Giants’ bid for the 1908 pennant, a hotly contested race that turned on the infamous “Merkle Boner” and left New York one game away from the pennant. But as the authors note, Donlin was “a hot-headed brawler who drank too much.” Nevertheless, The Sporting News noted that “the fans idolize the dashing, fleet-footed Donlin.”  Lyle Spatz Lyle Spatz He could hit, run, argue and fight, and Donlin sat out due to contract disputes, and later, when work on the stage proved to be more lucrative. Donlin began his career as a pitcher but soon switched to the outfield, and he became a fan favorite. “It was his jaunty, fighting air which made him the idol of the sports world,” screenwriter Jean Plannette said in 1930. Spatz and Steinberg list a litany of scrapes involving Donlin during the early years of his career. His swagger and short fuse would result in some memorable incidents. In 1900 he was slashed in the face after taunting a bar patron in St. Louis. During the 1901 season, Donlin threw a bat at umpire Jack Sheridan, and a fracas in a Baltimore theater in 1902 resulted in his pleading guilty to charges of “common assault” after he struck a woman who was a cast member in a Ben-Hur play. In 1906, he was arrested after punching a train conductor and pulling a gun on a porter. It is a common thread that Spatz and Steinberg follow as Donlin’s career continued. He was a talented player who could not resist a drink or the good life, and that invariably led to trouble. “He would fight at the drop of a hat,” St. Louis sportswriter Sid Keener wrote after Donlin’s death in 1933. “In fact, they didn’t have to do as much as tilt a skimmer to get Mike to swing his fists. “And yet, despite his desire to go out and look for trouble, everyone who knew Mike Donlin admired him.”  Mike Donlin was a sharp dresser off the field. Mike Donlin was a sharp dresser off the field. In addition to the brawls, Donlin had a heroic side, too. Spatz and Steinberg authors note that during spring training in 1905, Donlin and teammate Dan McGann saved an elderly woman from a hotel fire by climbing a ladder and bringing her down from a second-floor woman. What saved Donlin’s life, the authors write, was his relationship and marriage to his first wife, Mabel Hite. She was “a unique comedic talent” who introduced Donlin to vaudeville and the stage. The couple, Spatz and Steinberg wrote, had “a loving relationship and a remarkable partnership.” They were married on April 11, 1906, and the authors believe that Donlin was attracted to Hite because “she would bring stability and love to his life, which had had so little of either.” Hite was diminutive but forceful and made Donlin fly straight, “or else” the marriage would be over. The lure of the theater would draw Donlin away from the diamond. He and his wife wrote and appeared in Stealing Home, a one-act play in late 1908 that received positive reviews because Hite’s comedic ability carried the show. Donlin would waver over the next few years, the authors write. Baseball or theater? The latter would win out over the next few years, because it was more lucrative. Donlin had asked the Giants for an $8,000 salary in 1909 but was turned down. He and his wife made much more as actors touring the country, even though Donlin played second fiddle to his wife. “On the stage his talent was indistinguishable from hundreds of other supporting players,” the authors wrote. “But the stage offered far more money, and more important, he would be with Mabel.” Donlin returned to baseball in 1911 with the Giants but was soon traded to last-place Boston. Hite, meanwhile, began experiencing headaches and collapsed on stage during a 1912 performance. Reports at the time suggested she was suffering from intestinal cancer, and Hite died on Oct. 22, 1912. Out of the majors by 1914 after a stint with the Pirates, Donlin remarried and returned to the stage. He married Rita Ross on Oct. 20, 1914 — a member of the musical comedy team, Ross & Fenton — and began appearing in vaudeville. Donlin was able to reinvent himself during the 1910s, making the transitions from baseball to vaudeville and finally to motion pictures. He starred in the film Right Off the Bat, turning in a performance that was “a distinct surprise” and “could pass as a film lead on ability alone.” Donlin would continue to bounce between acting and baseball , but gravitated more toward film. He played small parts in many of them, at times not even receiving a credit for his role. He was not just “any extra.” “He became a beloved figure on the lots of Hollywood,” Spatz and Steinberg wrote. Despite suffering a “mysterious illness,” Donlin would appear in silent films with John Barrymore in Sea Beast and with Buster Keaton in The General. But by this time, Donlin’s once bountiful finances had dwindled, and he was unable to pay for medical expenses in 1927. He still remained relevant in entertainment, drawing positive reviews for his appearance in the 1930 play This One Man. He also appeared in more than 30 films between 1930 and 1933. Donlin died on Sept. 24, 1933, with The Associated Press attributing the cause to an “athletic heart.” He was featured in bit parts of films that were released two years after his death. Donlin, who was born in Peoria, Illinois, would be inducted into the Greater Peoria Sports Hall of Fame in 2016. The authors concede that while Ross was married to Donlin for the last 19 years of his life, little was known about her. The authors said she was “an almost invisible part of this story.” She is listed with Donlin in the 1920 census in Idaho (both listed their occupations as “actors”) and in the 1930 census they were living in Beverly Hills, California. It is a good bet that many casual baseball fans had never heard of Mike Donlin. But when he died, tributes flowed. Even Grantland Rice penned a long poem in his honor. “I still recall your swagger — and your easy careless grace,” Rice wrote. Humorist Will Rogers wrote that Donlin “couldn’t knock as many balls out of the park as Babe (Ruth), but he could knock more men out of it.” Spatz and Steinberg capture Donlin’s colorful personality in a richly detailed, well-researched work. They do a nice job explaining the history of vaudeville and the early years of the movie industry, and their play-by-play of Donlin’s glory years in baseball — particularly with the Giants — is well documented. It would have been great to learn how Donlin lost his money during the 1920s, whether by bad investments, alcoholism or medical issues. But the authors do a fine job in orchestrating a complete picture of Donlin. Drama always seemed to surround Mike Donlin, but he managed to make the best of it. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1984 Fleer baseball set:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1984-fleer-baseball-featured-snakes-umbrella-hats-and-other-fun-cards/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about two Washington state men who are accused of selling Pokemon and sports cards at inflated rates by allegedly passing them off as highly graded cards by PSA:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/duo-accused-of-selling-sports-pokemon-cards-with-fraudulent-grades-that-netted-over-2-million/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Parlay at Graybo's, a new idea that combines a traditional card shop with a traditional sports bar:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/richmond-businessmen-combine-card-shop-with-sports-bar/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Gary Longordo, a longtime artist and collector whose items are part of an auction that ends on Sunday:

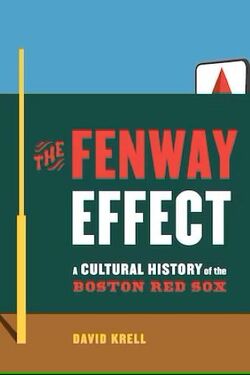

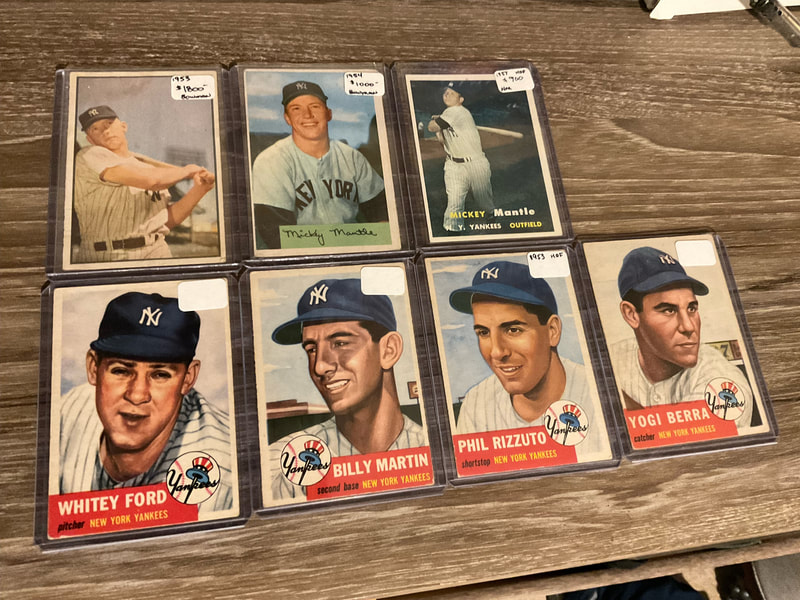

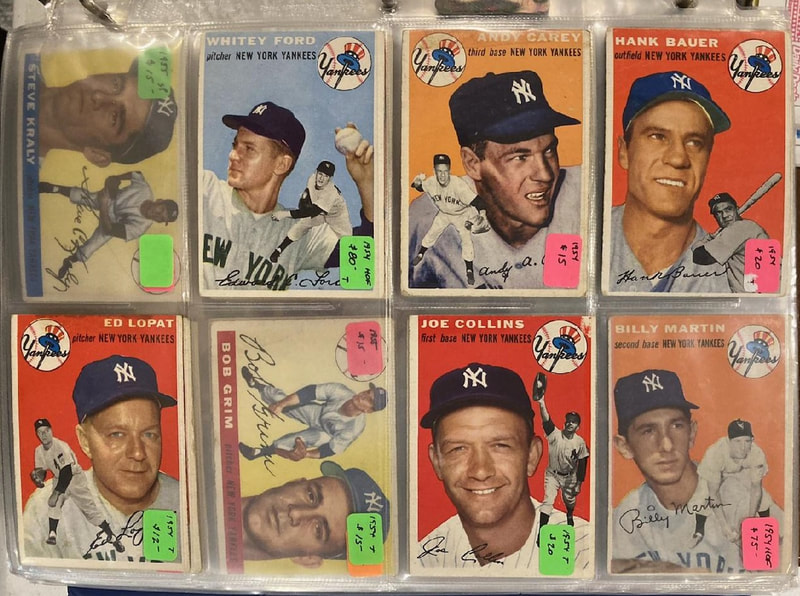

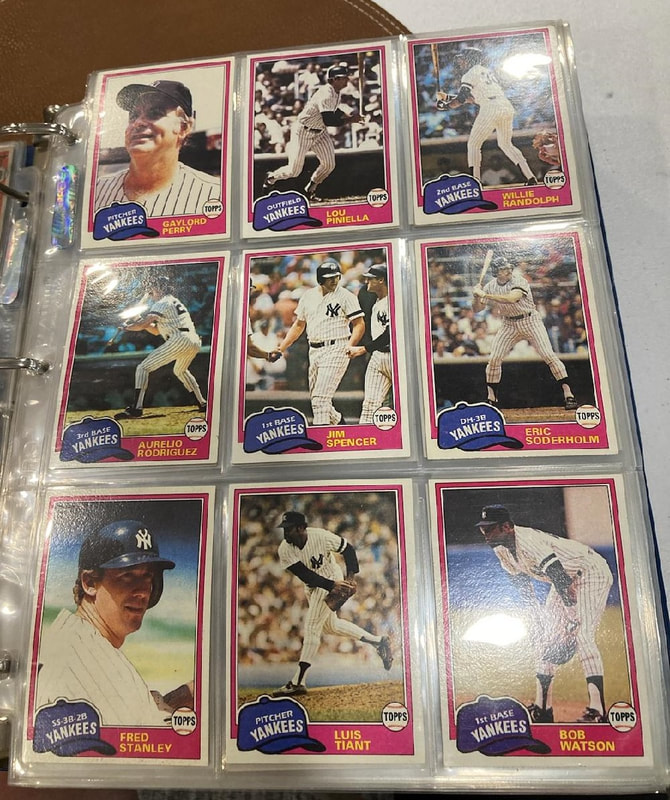

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/frosting-on-the-cake-longtime-artist-gary-longordo-selling-sports-memorabilia-collection/  It used to be that being a Red Sox fan was like being Eeyore in a Winnie the Pooh movie. You know, resigned to defeat or just knowing that something bad was about to happen. And for nearly a century, it sure seemed that way for Red Sox Nation. You can rattle off names or sentence fragments to a Sox fan and they will know what it means. No need to elaborate. Bucky Dent. Bill Buckner. One pitch away. Leaving Pedro in the game. Tony C. Tracy Stallard. Enos Slaughter and Johnny Pesky. Denny Galehouse. And of course, Babe Ruth and the Curse of the Bambino. But always, the Fenway faithful remained true. Finally, they were rewarded with World Series victories in 2004, 2007, 2013 and 2018. “They’re not the tragic, accursed figures of not so long ago anymore,” Jayson Stark wrote in 2008. Call it the Fenway Effect. That is what historian David Krell explores in The Fenway Effect: Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox (University of Nebraska Press; $34.95; hardback; 250 pages), framing the Red Sox as a cultural phenomenon in New England. Krell is no stranger to writing about the effect of baseball teams popular culture. He wrote “Our Bums”: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory, and Popular Culture (2015) and edited The New York Yankees in Popular Culture (2019) and The New York Mets in Popular Culture (2020). Whether their teams won or lost, Red Sox fans remained “Boston Strong,” and that is how Krell opens The Fenway Effect. He revisits David Ortiz’s profane but utterly appropriate speech days at Fenway after the bombing at the Boston Marathon in April 2013. “I never got booed at Fenway Park, and that’s why I ride and die with those fans,’” Ortiz said in a February 2023 interview.  The Boston area was blessed with the Celtics dynasty in the NBA during the 1960s and the New England Patriots rolling to nine Super Bowl appearances and six titles over the past quarter century. But the Red Sox were different. The emotional tug was so much stronger. Every disappointment brought their fans closer. “Expecting something bad is going to happen is just being a pessimist, but knowing that you are going to be hit by a garbage truck in the butt while picking up your dog's (excrement) — that is being a Red Sox fan,” David Needle wrote in 2001 for The Tufts Daily. But that was before the Curse of Bambino was exorcised in 2004. That was the year the Red Sox came back from a 3-0 deficit in the ALCS against the hated New York Yankees to sweep the next four games. Then, Boston beat St. Louis in the World Series for the city’s first MLB title since 1918. The Fenway Effect goes beyond baseball. Krell writes about the iconic Citgo sign that towers over the Green Monster, calling it “a bedrock of Red Sox culture.” It is more than just an advertisement, and as Alison Frazee, the executive director of the Boston Preservation Society stated, “most viewers don’t associate it with the Citgo brand,” instead linking it to the Red Sox. Krell writes an interesting history of the sign, noting that there is even a miniature version of Fenway Park for a Little League park that also includes a Citgo sign. Cities Service originally had a gas station behind the left field wall at Fenway, but as time went on, the sign became a signature feature of the ballpark, and not the oil company. And at times, it was a controversial issue among Boston politicians. Fiction has played a park in Fenway’s lore, with the successful television series “Cheers” showcasing former pitcher Sam Malone owning a bar where everybody knows your name. Ted Danson’s recovering alcoholic character — running a bar, no less — and his cast of regulars gave viewers someone to identify with. It also put Boston on the television map, Krell writes. For decades, television shows appeared to be based out of New York City, from I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners to even Car 54, Where Are You? Other shows were based out of California, like The Beverly Hillbillies, The Munsters and Mr. Ed. Krell writes that the most notable show before Cheers based out of Boston was Banacek, about an intrepid insurance investigator. I’d argue in favor of Paper Chase, which starred John Houseman as the impossibly crusty Harvard Law School professor (Houseman won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in the film version). Given Boston’s longtime inferiority complex, it seemed only fitting that the regulars at Cheers thought that Red Sox star Wade Boggs was an imposter sent to prank them by a competing bar. Krell also mentions Fever Pitch, the 2005 romantic comedy starring Jimmy Fallon as obsessed Red Sox fan Ben Wrightman and Drew Barrymore as Lindsey Meeks. “Lindsey, will you go to Opening Day with me?” Fallon asks while dropping to one knee and opening a velvet jewelry box. You get the idea. Entwined with the Red Sox since the days of Ted Williams is the Jimmy Fund, which benefited cancer patients at Children’s Hospital in Boston. Krell outlines the history of the charity, how the Splendid Splinter would visit children and insist that they be kept private. When a child told Williams that he wanted to become a baseball announcer, the Red Sox star arranged for Boston play-by-play legend Curt Gowdy to visit him, Krell writes. Then there is Narragansett Beer, which was always linked to Gowdy — “Hi Neighbor! Have a ’Gansett,” he would say as he came on the air. Gowdy, Krell writes, provided New Englanders with “ cultural touchstone” during a progressive and “sometimes volatile” period. Gowdy was smooth, conversational and was a soothing voice from 1951 to 1965 in Boston, a period where the Red Sox finished as high as third place in the American League three times. From 1961 to 1965, Boston finished sixth, seventh, eighth (twice) and ninth in the 10-team A.L. race. Red Sox fans needed Gowdy’s reassuring voice — and lots of ’Gansetts. Krell revisits many difficult games for the Red Sox, including the 1978 playoff game against the hated Yankees and the disastrous end to Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. But there is also a recap of one of the Fall Classic’s most memorable contests — Game 6 of the 1975 World Series, when Carlton Fisk willed a long fly ball to stay fair for a dramatic home run. Krell also gives credit to Bernie Carbo, whose three-run homer tied the game and Dwight Evans’ catch in the 11th inning to rob Joe Morgan of a home run, setting up Fisk’s heroics one inning later. Many baseball fans remember Carbo’s pinch-hit blast; only truly diehard fans recall Evans’ catch and throw that doubled up Ken Griffey Sr. to end the inning. Krell’s narrative is crisp and casual, lending a relaxed air to his subject. The former MSNBC producer has also written 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK in 2021; and last year’s Do You Believe in Magic?: Baseball and America in the Groundbreaking Year of 1966. The Fenway Effect is a more contemporary look at a city that loves its baseball. There have been many books written about the Dodgers, for example. But very few authors have taken the path Krell did, examining the cultural effects of what it means to being a Red Sox fan. He ends the book with “Voices of the Fans,” with diehard Sox fans unabashedly revealing their love for the team. Krell’s effort provides a different look at a city and franchise that both enjoy being out front. They are no longer like Eeyore. Like singing along to “Sweet Caroline” in the bottom of the eighth inning, reading about the culture of the Red Sox never felt so good. To be honest, I prefer “Dirty Water” by The Standells. That opening guitar lick is awesome and they sum up a Red Sox fan’s feelings perfectly: “Boston, you’re my home. Oh, you’re my No. 1 place.” “Sports are an integral part of Boston’s culture, and if you live here, it’s worth being a fan,” Cloe Axelson wrote in September 2023. Krell shows the reader why that is so with another solid effort. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a collection of Yankees cards and memorabilia bought by New York card shop owner Eric Biletzky:

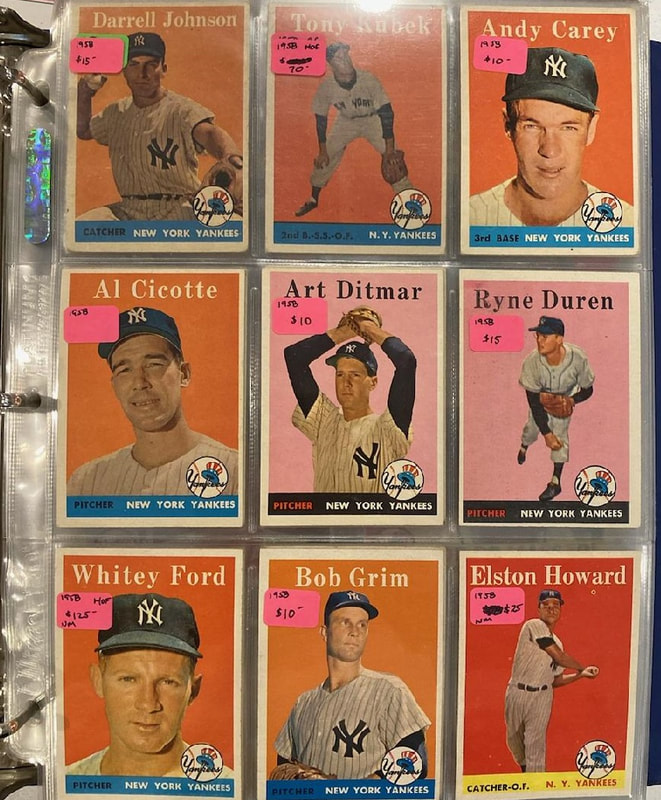

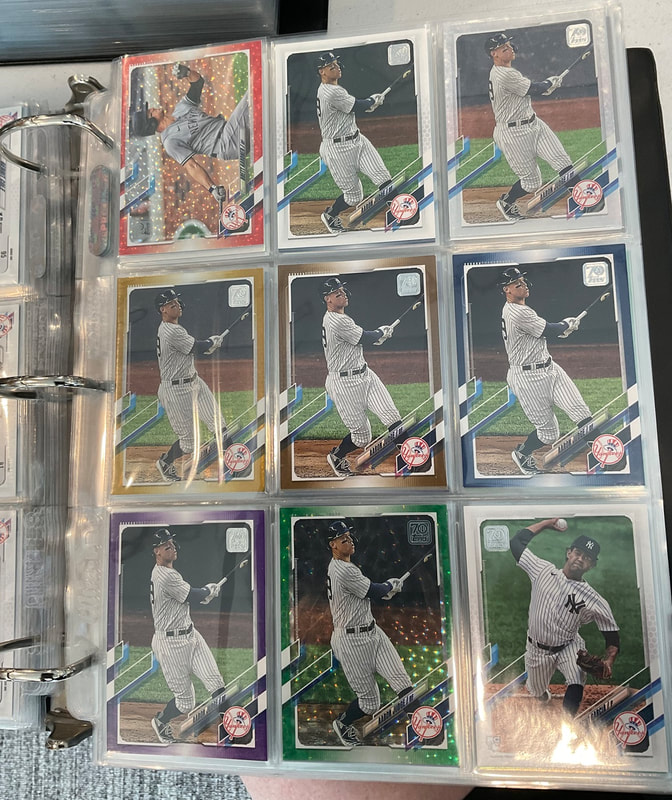

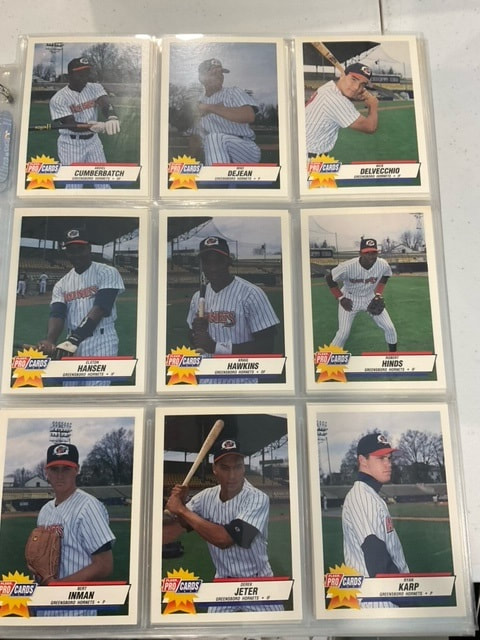

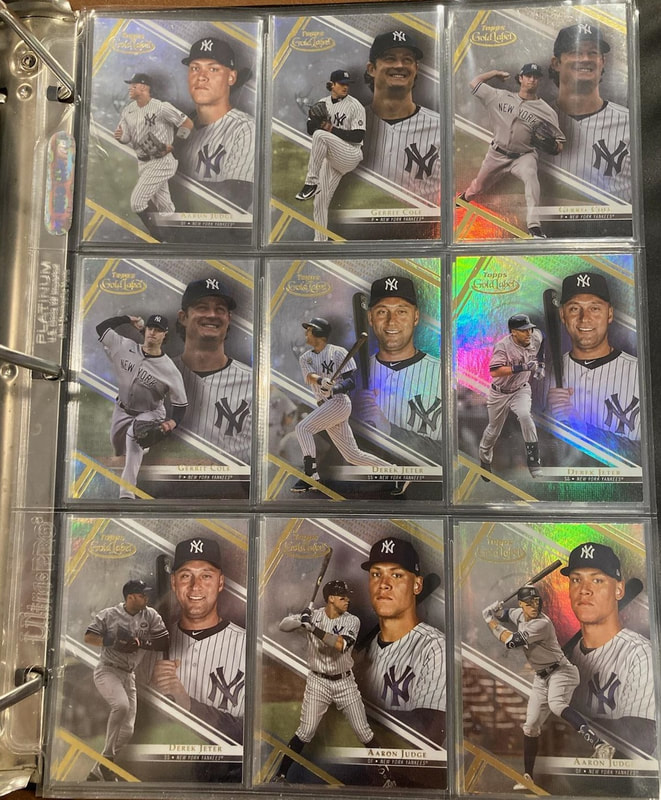

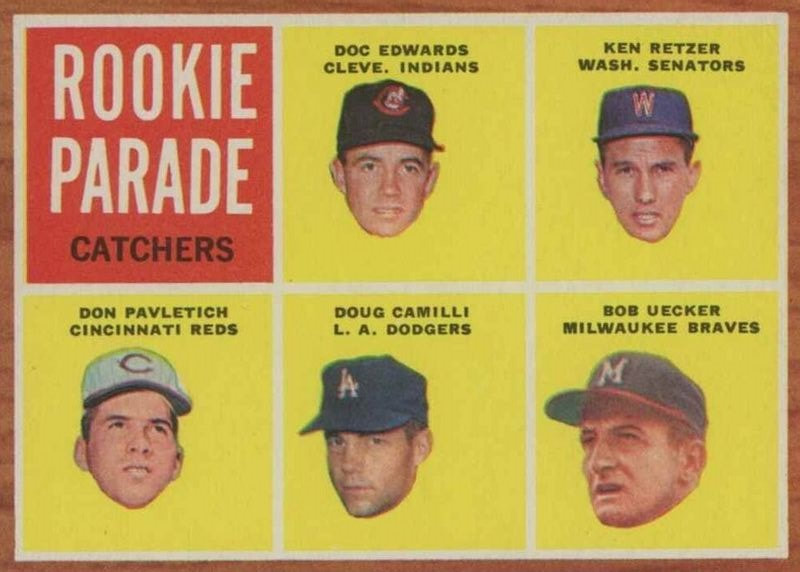

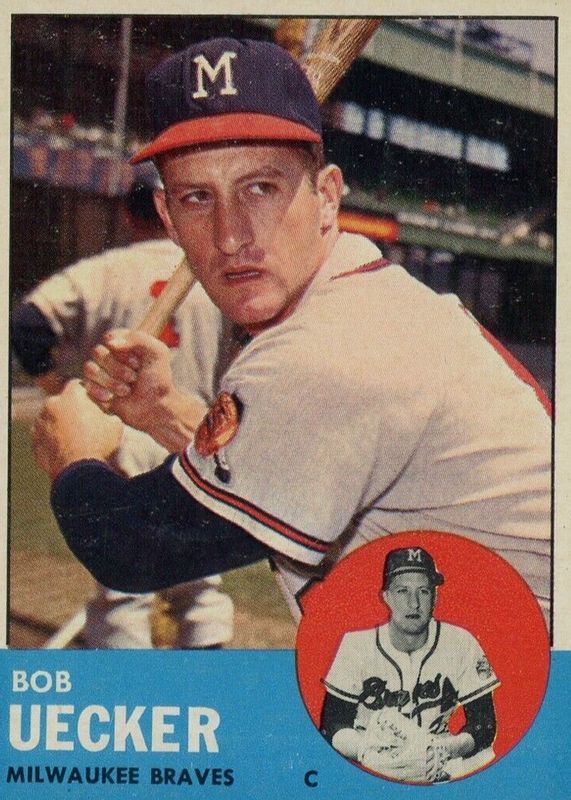

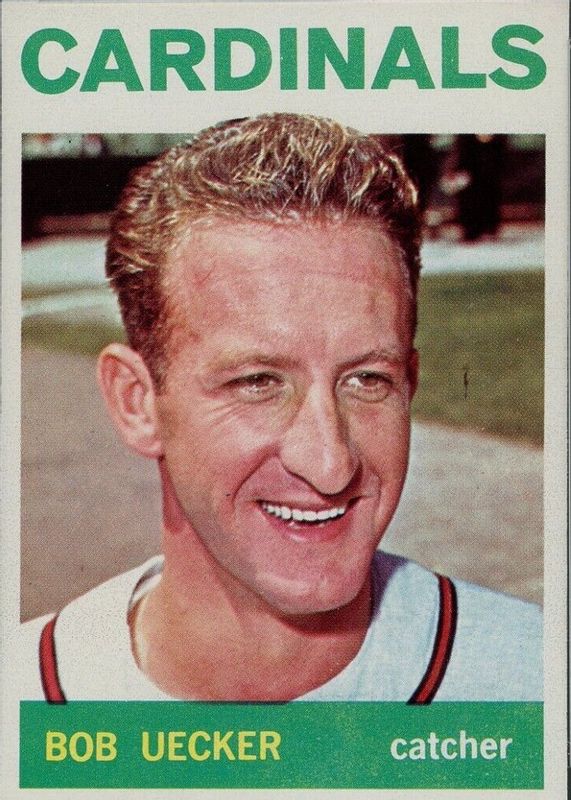

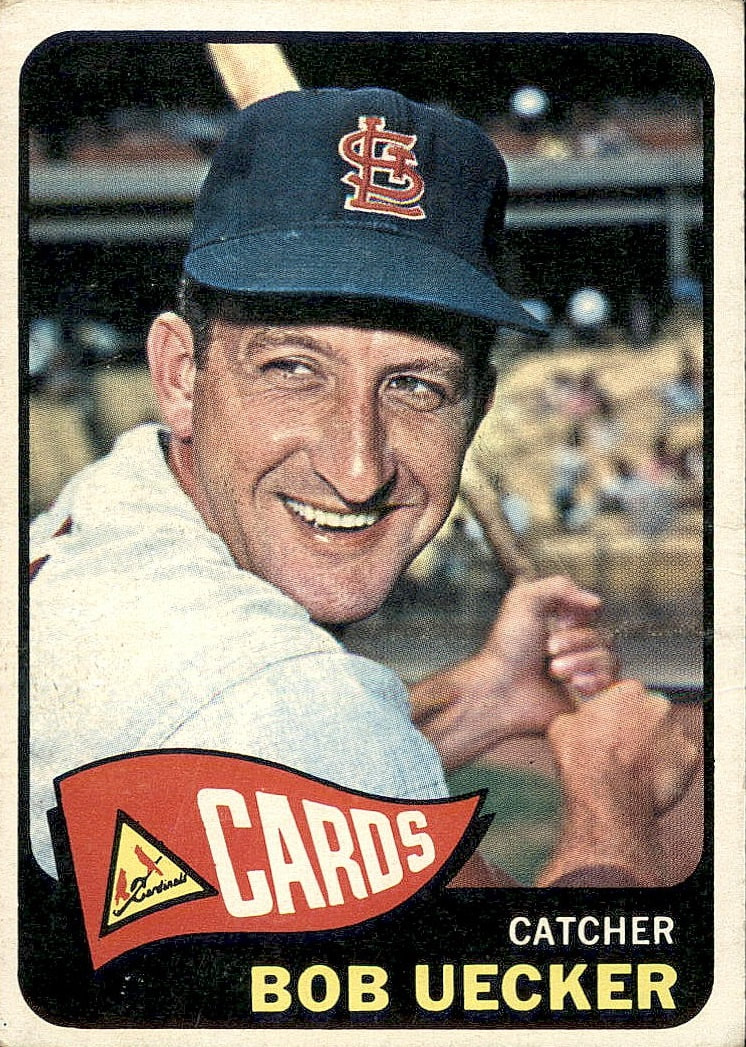

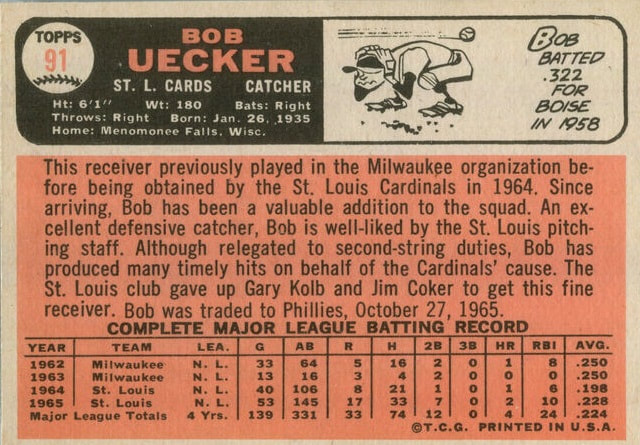

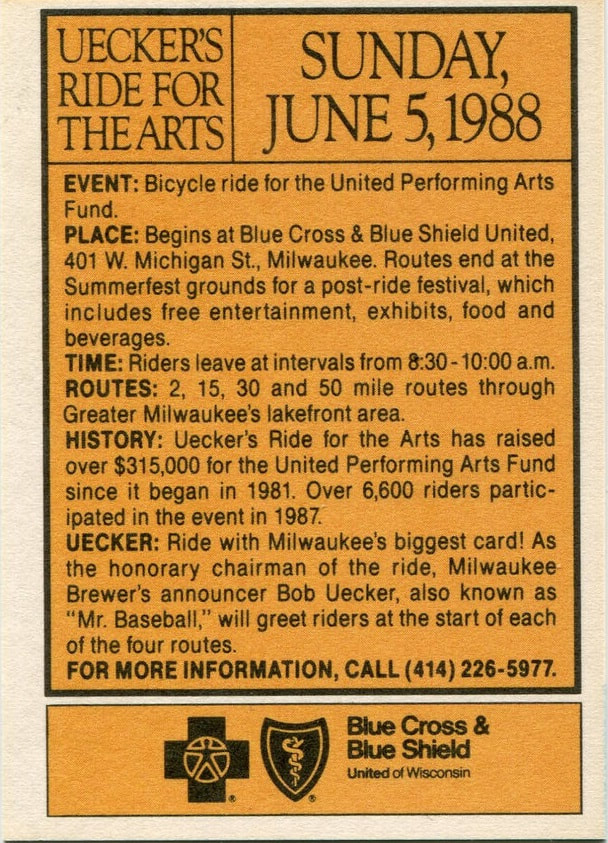

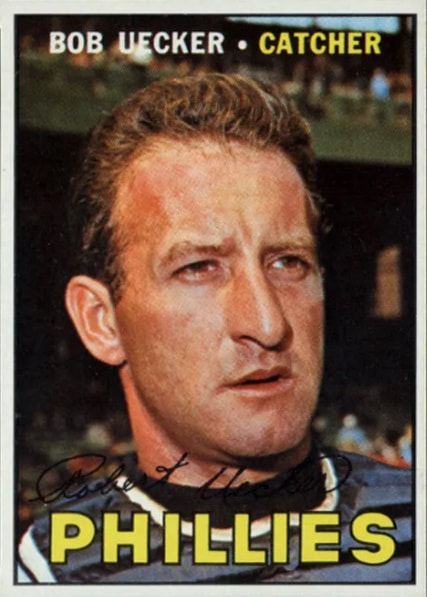

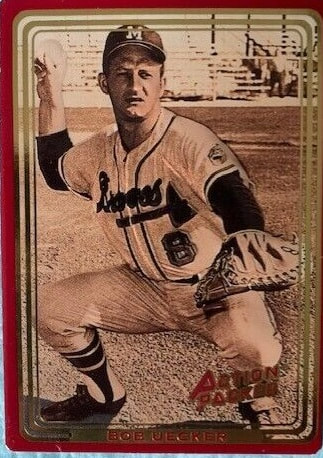

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/new-york-shop-owner-bought-yankee-doodle-dandy-of-a-collection/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily celebrating the cards of Bob Uecker, "Mr. Baseball," who turned 90 in January.

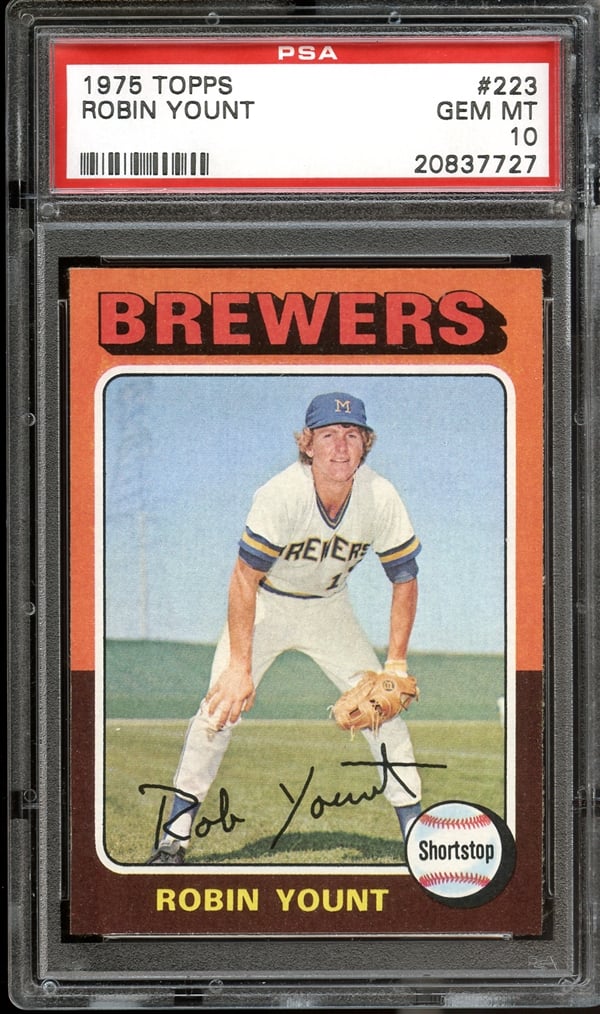

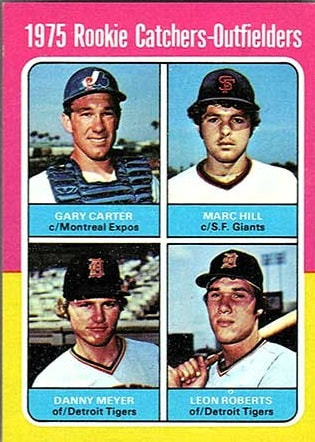

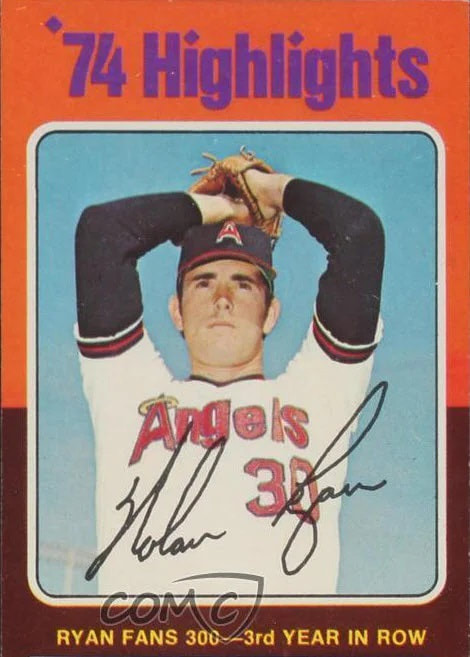

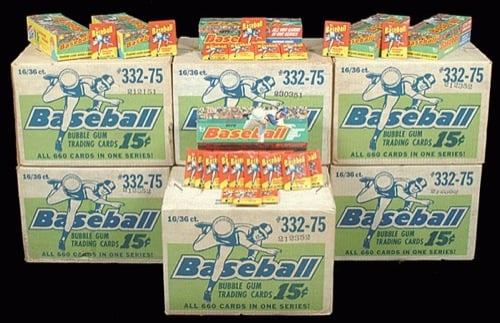

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/bob-uecker-baseball-cards-guide/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1975 Topps baseball set:

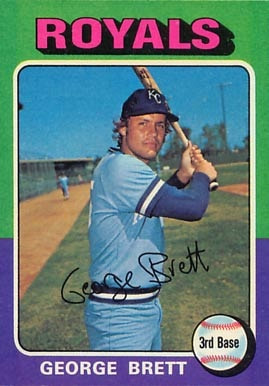

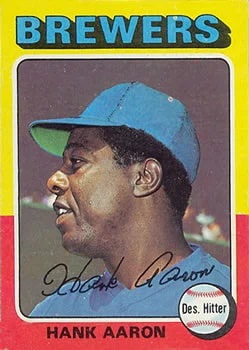

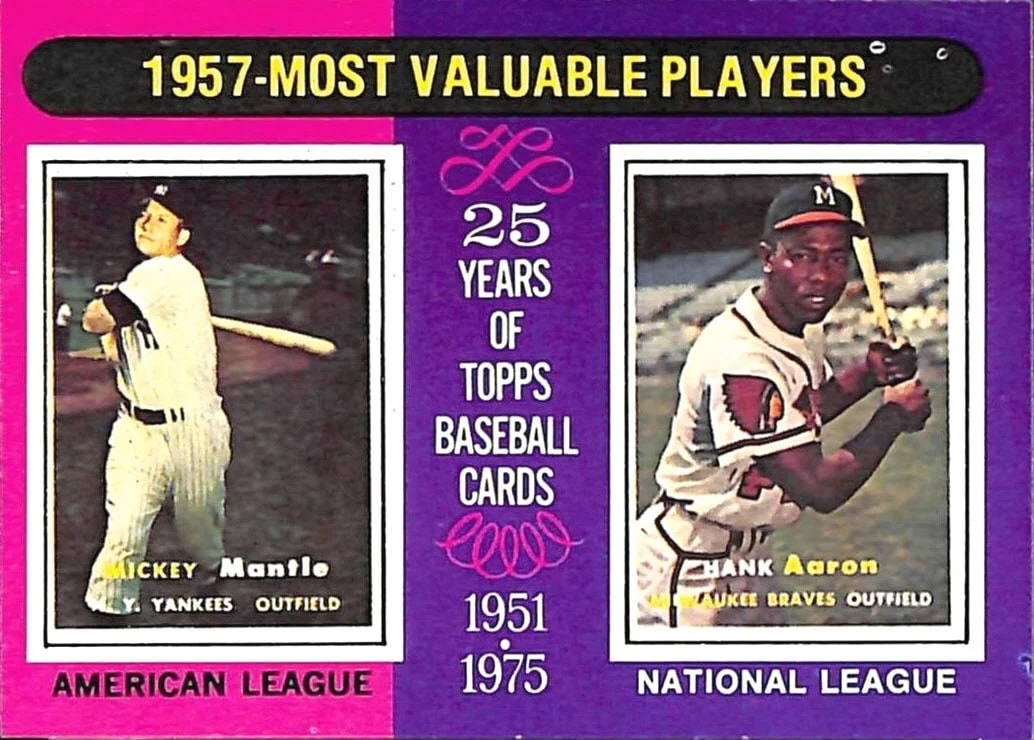

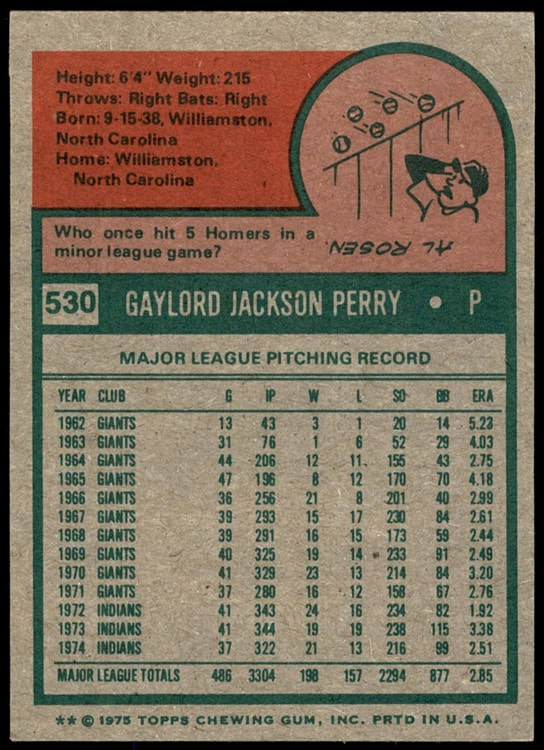

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1975-topps-baseball-featured-key-rookies-big-stars-colorful-design/

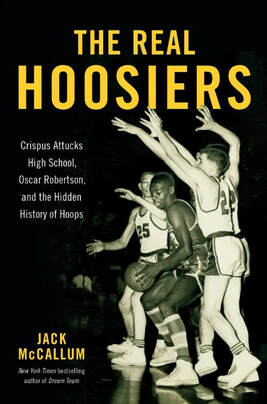

Jack McCallum brings his “A” game in his latest book.

A fixture at Sports Illustrated for three decades, McCallum knows when to pass and when to shoot. The basketball analogies are appropriate. In The Real Hoosiers: Crispus Attucks High School, Oscar Robertson, and the Hidden History of Hoops (Hachette Books; hardback; $30; 336 pages). McCallum digs deep into the psyche of Indiana basketball, a sport viewed with reverence by residents of the Hoosier state. McCallum strips away the underdog, feelgood Hollywood narrative that made “Hoosiers” such a wonderful movie when it was released in 1986. He instead focuses on the harsh realities of racism, integration and segregation during the early 1950s in Indiana, when Crispus Attucks High School rose to prominence. The school fielded the first all-Black team to win a high school state title in the nation, and was the first to go undefeated in Indiana with a 31-0 mark in 1956. It was also the first squad from Indianapolis to win a state crown. While the team lost to unheralded Milan in the 1954 semifinals, Attucks would go 61-1 over the next two seasons, winning back-to-back state titles. The teams would be inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, each squad earning enshrinement 50 years after they played. “Their success changed things in (Indianapolis) and went well beyond the realm of high school sports,” Chris May, the Hall of Fame’s executive director who retired after 15 years in 2022, told Sports Illustrated in 2018. Attucks had its star player and star coach, with Oscar Robertson on the court and Ray Crowe from the bench. Robertson declined to be interviewed for McCallum’s book, which was not a surprise; he also refused to talk to Sports Illustrated for what became a long feature in 2018 about Crispus Attucks High School.  Jack McCallum. Jack McCallum.

Robertson already spoke his piece in his 2003 autobiography, The Big O, but his refusal to lend his voice to McCallum’s narrative is actually a blessing. The subjects McCallum interviews and the extensive research he did provide a deeper, richer portrait of a state invariably called the most northern state in the South — or the most southern state in the North. Take your pick. Less charitably, Indiana has been called the middle finger of the South.

One of my history teachers at the University of Florida, David Chalmers, wrote an exhaustive history of the Ku Klux Klan during the 1960s, Hooded Americanism, and Indiana had more than a bit part. Instead of riding horses to cross-burnings, Klansmen in 20th century Indiana would pull up to gatherings in Winnebagos, he once lectured. Those prejudices did not go away easily, even after the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which ruled that segregating children based on race was unconstitutional. Enforcing that decision proved to be slow and torturous, based on personal experience. The high school I attended in Delray Beach, Florida, from 1971 to 1975 did not become fully integrated until the 1970-71 school year, and it took a court order for Palm Beach County to enforce it among all the schools in the county. Robertson, now 85, was a beloved player at every level of basketball. His enshrinement into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1980 was a foregone conclusion. Robertson changed the game with his vision as a court general. Averaging a triple-double during the 1961-62 season was an astounding feat. As a high school player, Robertson was named Indiana’s “Mr. Basketball” for 1956. Robertson retired from the NBA in 1974 after scoring 26,710 points, handing out 9,887 assists and collecting 7,804 rebounds during 1,040 regular-season games, according to Basketball-Reference.com. He won an NBA title with the Milwaukee Bucks in 1971 with Lew Alcindor, who later changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He was also a driving force on the labor side, helping players to bargain more effectively for their services. Robertson’s talents “snuck up on you because his brilliance came from fundamentals, versatility, and, above all, consistency,” McCallum writes.

Noted for his 2012 book, The Dream Team, McCallum brings humor, snark and turns many a phrase in The Real Hoosiers, like dishing off no-look passes. His writing is every bit as breathtaking as Robertson’s court demeanor.

A favorite line: Bailey “Flap” Robertson, Oscar’s older brother, “could talk the shell off an egg.” Of Crowe, who had a 179-20 record in seven seasons at Attucks but was never named Indiana’s Coach of the Year, McCallum writes that he “commanded respect with a tough-but-fair demeanor and a way of getting along with everyone.” “A man comfortable in both the boardroom … and the locker room,” McCallum notes. And Crowe mostly knew how to hold his tongue, except in rare instances, but it is hard to imagine why. He was a basketball coach in Indiana, where for a half century “they had been hailed as geniuses, molders of men, pillars of small communities.” Except those men “were all white,” McCallum writes, noting with irony that Crowe grew up in the town of Whiteland, 19 miles south of Indianapolis. And there was the rub. The other rub was the officiating, where white referees would whistle calls against Black squads in tight games. Crowe took over the basketball program at Attucks before the 1950-51 season. The Tigers reached the 1951 state semifinals, featuring Hallie Bryant, Willie Gardner and Flap Robertson. A poor call against Bryant during the 1953 playoffs — he was whistled for charging when he was knocked to the floor by a pair of Shelbyville players — eliminated the Tigers from the playoffs. Attucks would lose to Milan in the ’54 semifinals. McCallum observes that Attucks players like Bryant “knew they were much more likely to get bad calls from white refs.” In a game during the 1951-52 season, Willie Gardner had fouled out and was sitting on the bench when he heard an official call a foul on him. “I’m right here,” Gardner said, standing up and raising his hand. Bernard McPeak, a respected Black referee from Pennsylvania, was finally allowed to officiate in Indiana after originally being rebuffed. But as McCallum notes, Crowe was not always happy to see him on the court, noting that McPeak was “bending over backwards” to avoid the appearance of giving Attucks any breaks. “He was killing us,” Crowe would say. “Be right without fear. Unfair victory is bittersweet,” was one of Crowe’s principles, McCallum writes. Another one: “No team can beat you at your best; right is unbeatable.” So, it is amazing that Crowe’s squads at Attucks High School were so right. From the start, the high school was built for the wrong reasons.

Robertson’s family lived in the Frog Island area of Indianapolis near the confluence of three rivers, “none of them pleasing.” The area was also known as Bucktown, Naptown or Pat Ward’s Bottoms. Robertson grew up viewing the Harlem Globetrotters as role models.

Attucks was built over the objections of the Black community, which did not want a segregated school. Civil rights activist John Morton-Finney called their opinions “downright hostile,” McCallum writes. There was even consternation over naming the school after Attucks, who was killed by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. “It does not appear that his services were such as to call for commemoration of his somewhat unrememberable name,” an unsigned article in the Indianapolis News noted. “Will the pupils of the school be able to remember it, and pronounce it?” And yet, McCallum writes, there was a “can-do attitude” about the school that was built to “keep Blacks in their place, built by haters, built to fail.” He spends the first chapter walking the halls of the high school, pointing out the notable graduates of the 97-year-old school. Not all of them were athletes; in fact, these alumni made solid impacts on society as a whole, in Indiana and beyond. Attucks integrated in 1970 by a court order and became a junior high school in 1986. It is now a magnet school for students in grades six through 12. But during Robertson’s time at the school, Attucks did not have a serviceable gym to play games; many of their home games were played at Butler University. Other schools, like Muncie Central, “played in a virtual palace,” McCallum writes. That gym held big-time acts like the Globetrotters, the Supremes, and Abbott and Costello, but at Attucks’ home gym, “you could barely fit all three Supremes, and you definitely couldn’t if you added Costello.” Long road trips to play games were common for Attucks, and finding food and lodging was problematic due to the racial mores of the time. Attucks’ first state title was bittersweet. Players were driven around the city on a fire truck as part of a motorcade but were not allowed to stop and celebrate at Indianapolis’ Monument Circle, a tradition for Indiana state champions. City officials were expecting riot-like conditions from Blacks celebrating if they had won the state title.

"There floated a sense of some unease in some segments of the white community, which had never engaged in wholesale racially integrated celebration,” McCallum writes.

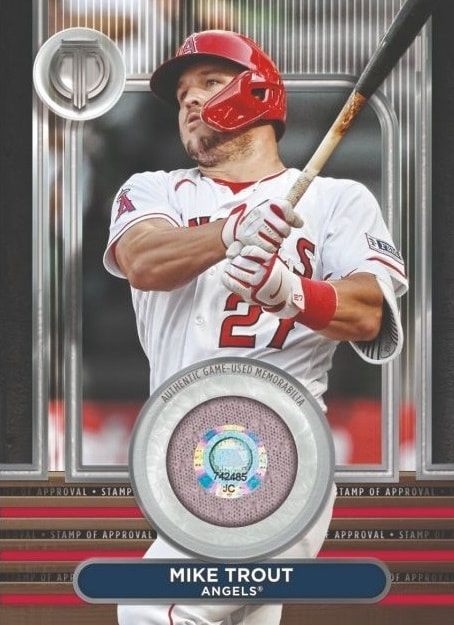

McCallum chronicles the key games in Attucks’ state title runs, including a semifinal win in 1955 against Muncie Central, where Robertson made a game-saving steal of a pass that was similar to Larry Bird’s theft against Detroit in the NBA playoffs three decades later. On March 19, 1955, the Tigers prevailed 97-74 against another all-Black school, Roosevelt High in Gary, to win it all. “At that age, we had no historical perspective on what it meant for two Black teams to play each other in that setting at that time,” Dick Barnett, a Roosevelt player who would go on to a 14-year career in the NBA, told Indianapolis Monthly in 2014. And then there is “Hoosiers,” the film that received two Academy Award nominations. It starred Gene Hackman, best supporting actor nominee Dennis Hopper and Barbara Hershey. Hickory High School, the small school coached by Hackman, mirrored the journey of Milan High, which stunned the field to win the 1954 crown. Crowe played the coach of the South Bend Central team that lost to Hickory High in the title game of “Hoosiers.” Flap Robertson also had a role. McCallum devotes a chapter to the movie, titled, “Separating Fact from Fiction in Hoosiers.” He notes that the real Attucks story has been “subsumed by the fictional story” and obscured historical truth. The film, as most Hollywood efforts have a tendency to do, took broad editorial license, and even though the story was fiction, it mirrored an actual event — sort of. Robertson and many of Attucks’ fans were furious, McCallum writes, “either with the movie, the misguided interpretations of it, or both, and that is entirely understandable.” Robertson wondered why the filmmakers “twisted the truth.” When Milan won the title in real life during the 1954 final, Muncie Central was a racially integrated team. “Hickory defeated a fictional team of Black players, coached exclusively by Black men, whose rooting section consists of Black men, women, boys and girls,” Robertson said. “Is the proverbial race card being played?” Screenwriter Angelo Pizzo defended the movie, noting that it was not a documentary or a docudrama. “It’s not 100% Milan,” he told McCallum. “These are completely new characters made out of whole cloth by me.” That being said, Hoosiers remains one of the great sports movies. I prefer Slap Shot, but perhaps that is because I liked old-time hockey and the Hanson brothers. The 1956 state champions were dominated by Robertson, who played a game “as coldly efficient as a Stasi agent.” On Feb. 10, 1956, he scored a career-high 62 points in Attucks’ 76-47 win against Sacred Heart. In the state tournament, he scored a championship game-record 39 points. When Robertson was asked if a 56-point effort for the University of Cincinnati against Seton Hall, which set a scoring mark at Madison Square Garden, was his biggest thrill, he said no. His career highlight was helping Attucks win a pair of high school state titles. “A Hoosier has his priorities,” McCallum writes. So does The Real Hoosiers. McCallum offers a well-researched, balanced look at a basketball program that broke down racial barriers in a city that was loathe to change. He also offers a sobering look at prejudice that was still prevalent 70 years ago. Readers should be aghast and angry at what took place during the 1950s, and no feelgood movie is ever going to erase that. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily previewing the high-end 2024 Topps Tribute baseball set:

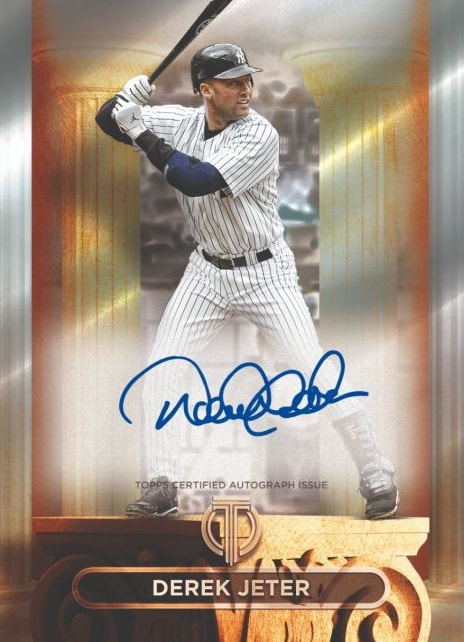

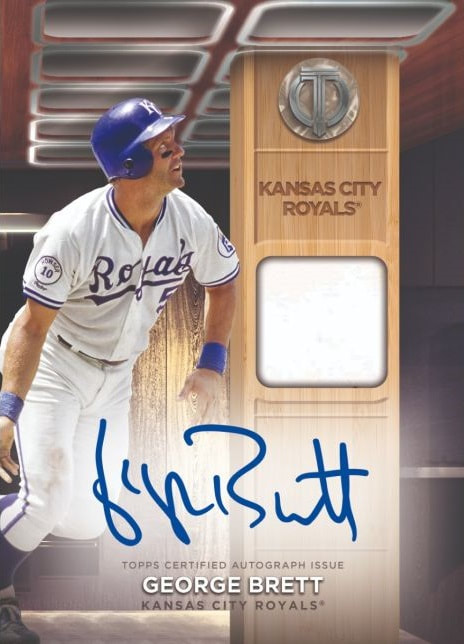

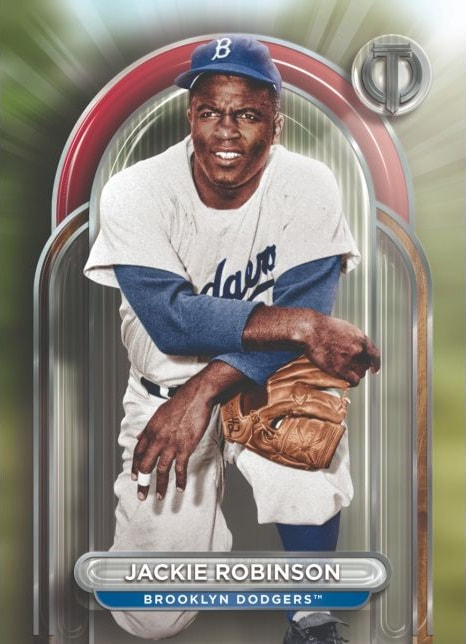

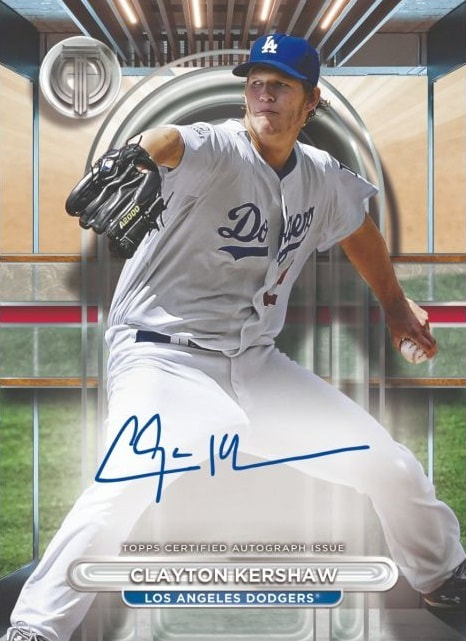

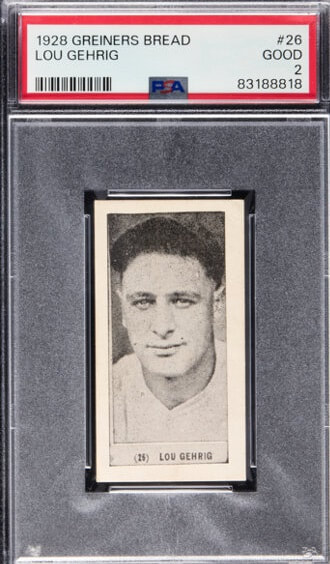

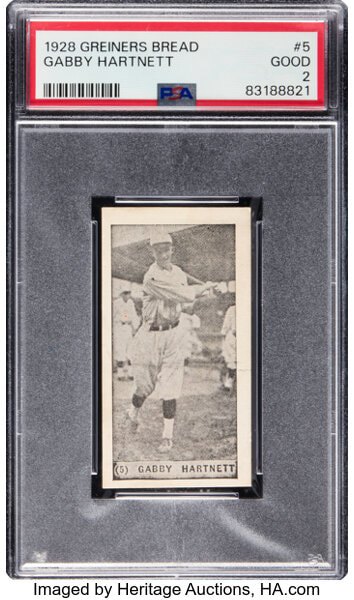

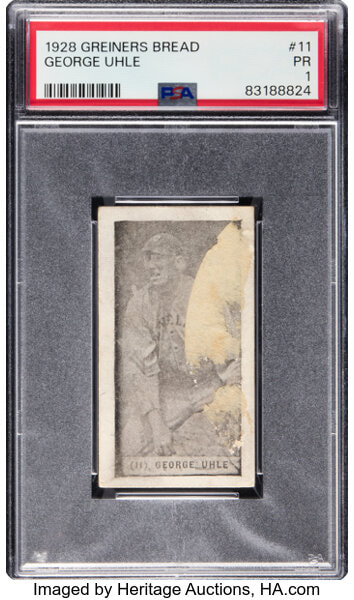

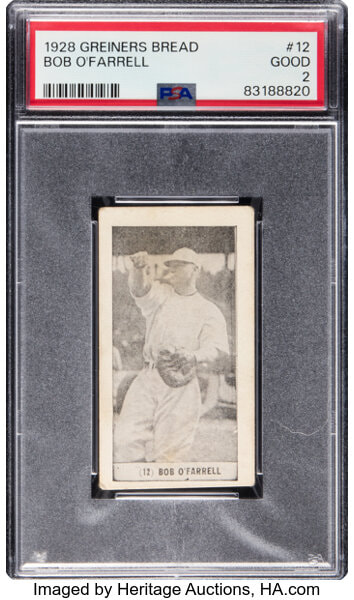

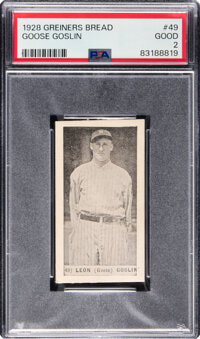

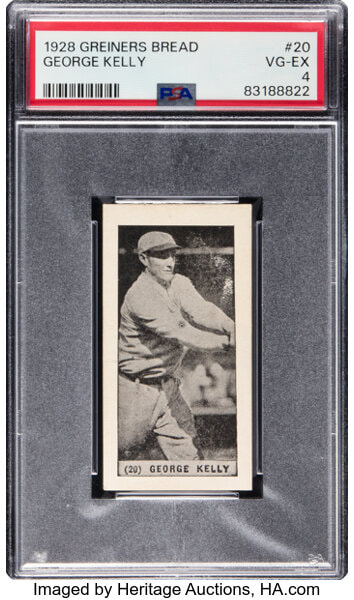

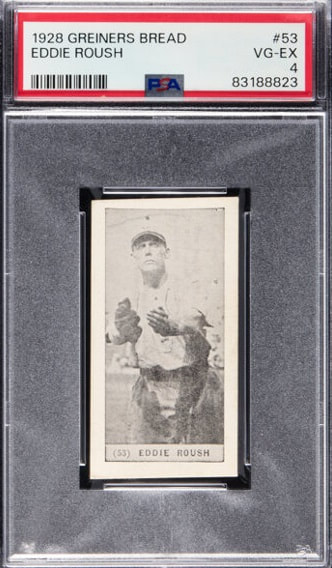

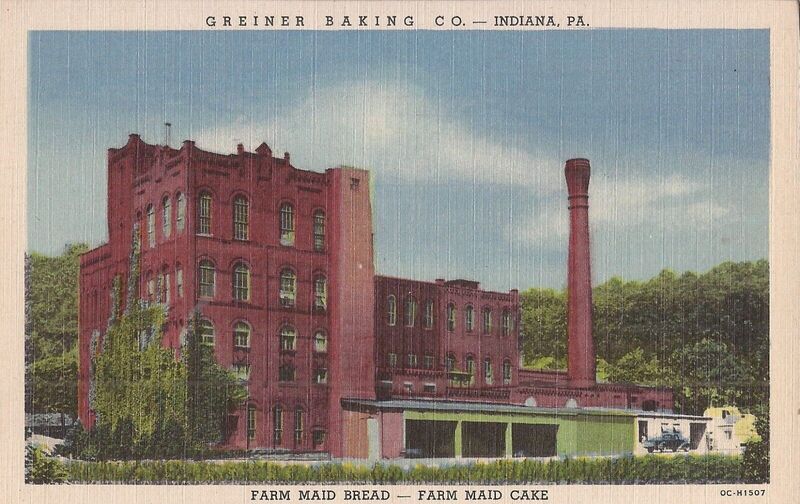

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2024-topps-tribute-baseball-information-release-date-checklist/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about seven 1928 Greiner Bread cards that are headed to auction:

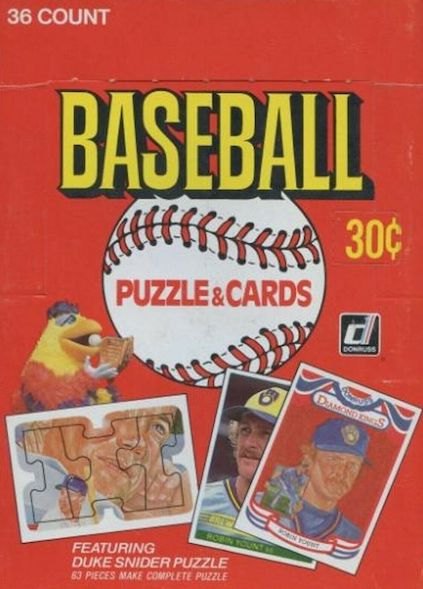

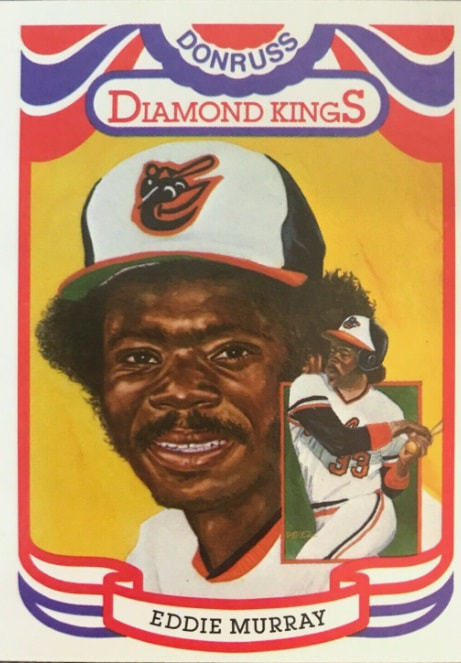

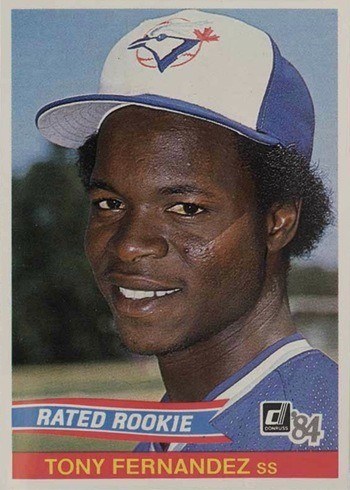

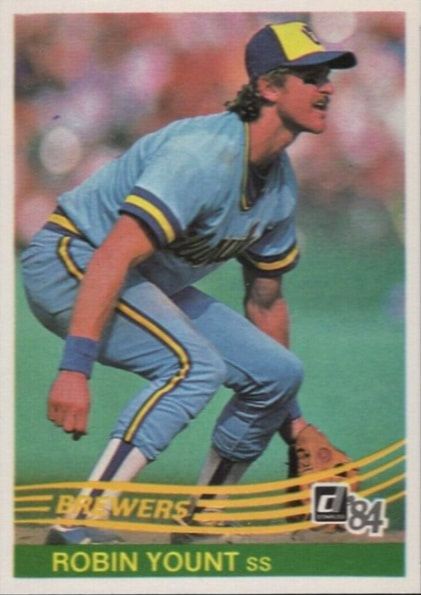

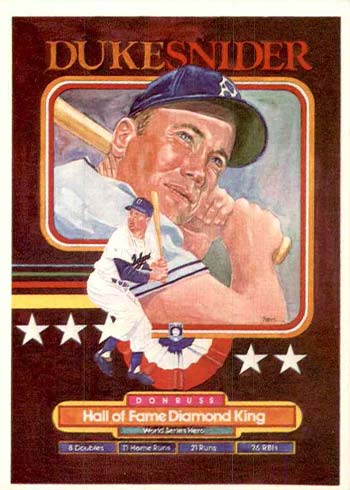

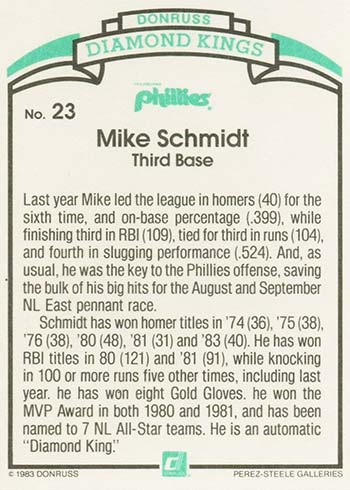

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/rare-1928-greiner-bread-cards-part-of-heritage-auctions-sale/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily, looking back at the 1984 Donruss baseball set, which is 40 years old this year:

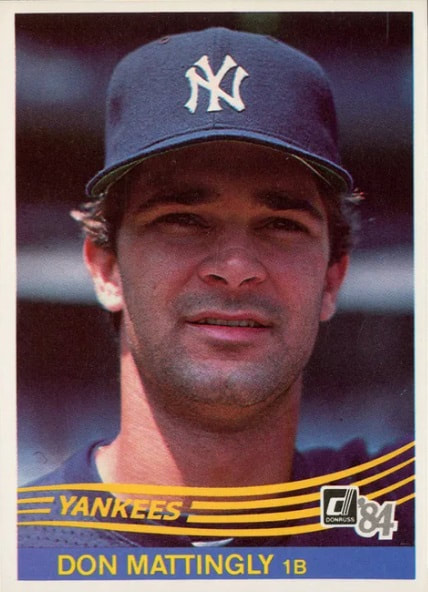

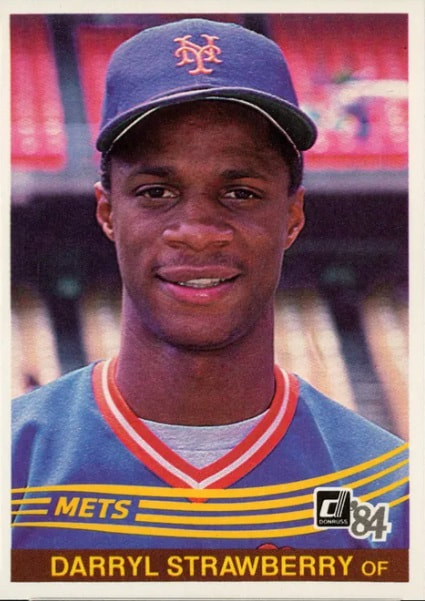

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1984-donruss-baseball-still-resonates-with-collectors-40-years-later/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an interview I had with Robert Grabe, Topps' senior graphics designer. We talked about the new design for the 2024 Topps Series 1 set, which dropped on Feb. 14.

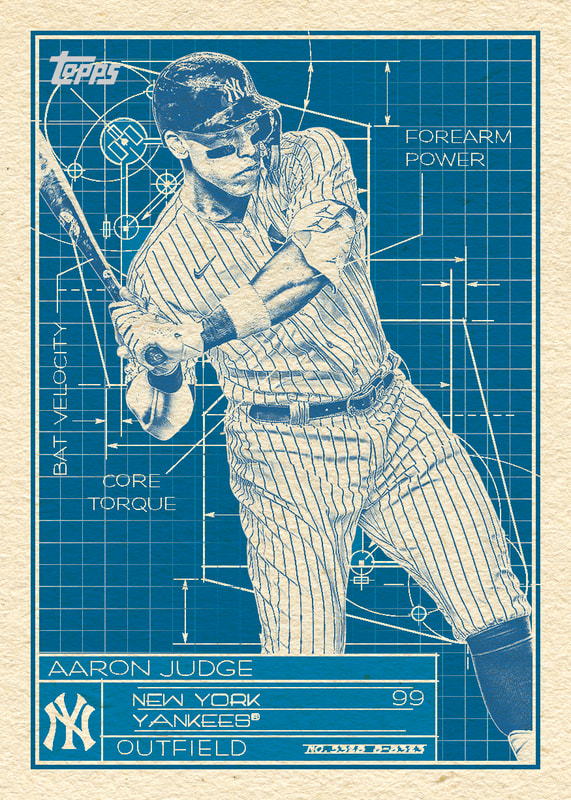

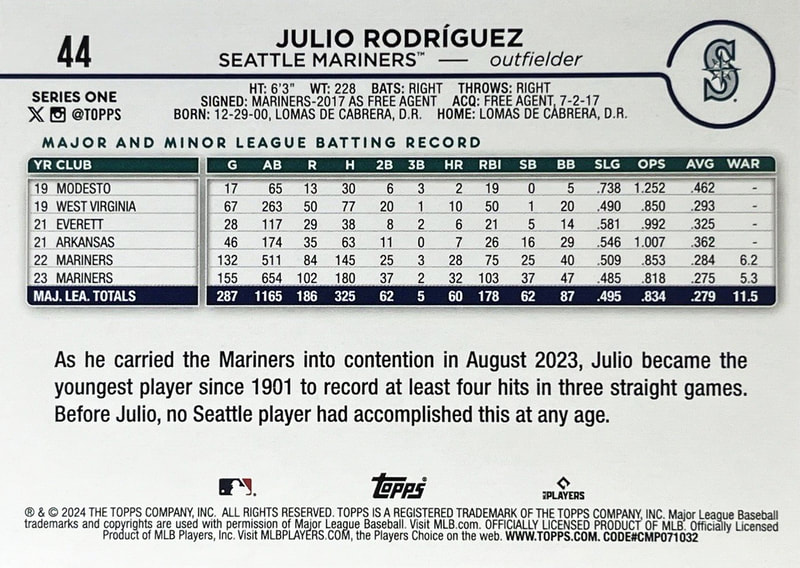

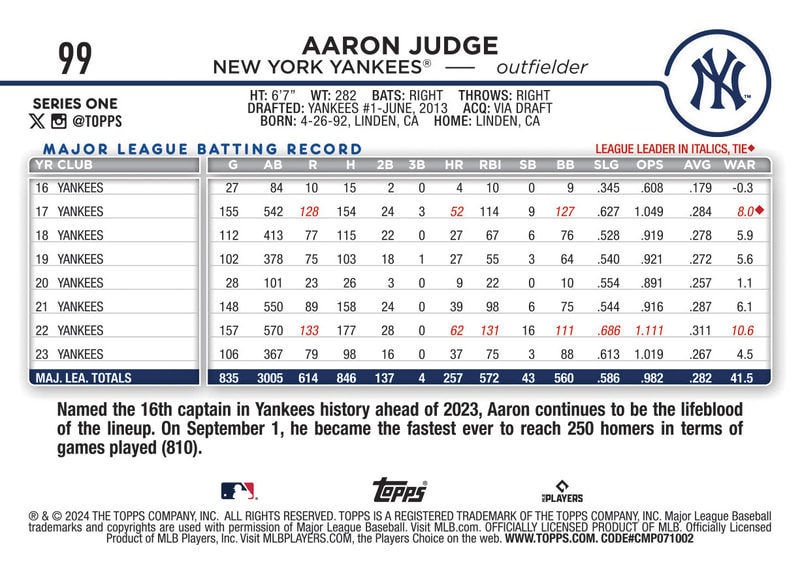

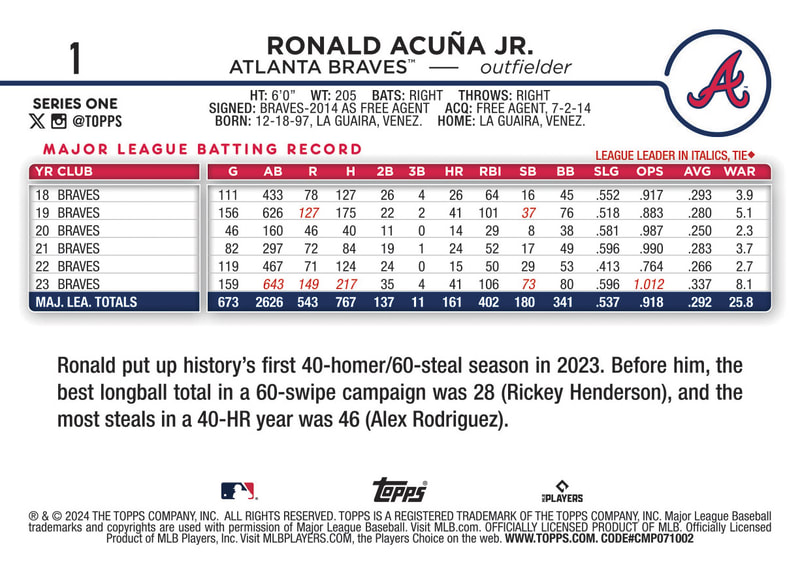

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/going-neon-2024-topps-series-1-designer-discusses-fresh-look-for-flagship-product/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a poster touting Albert Spalding's baseball tour that stopped in Australia in 1888-89:

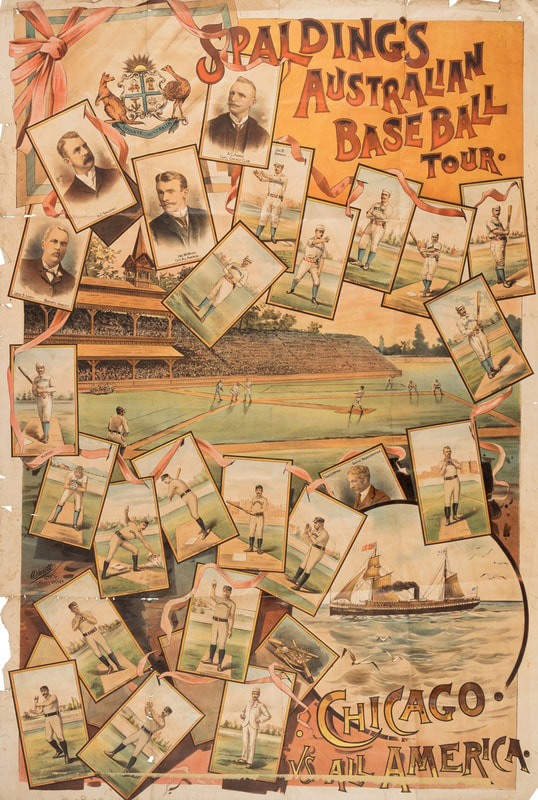

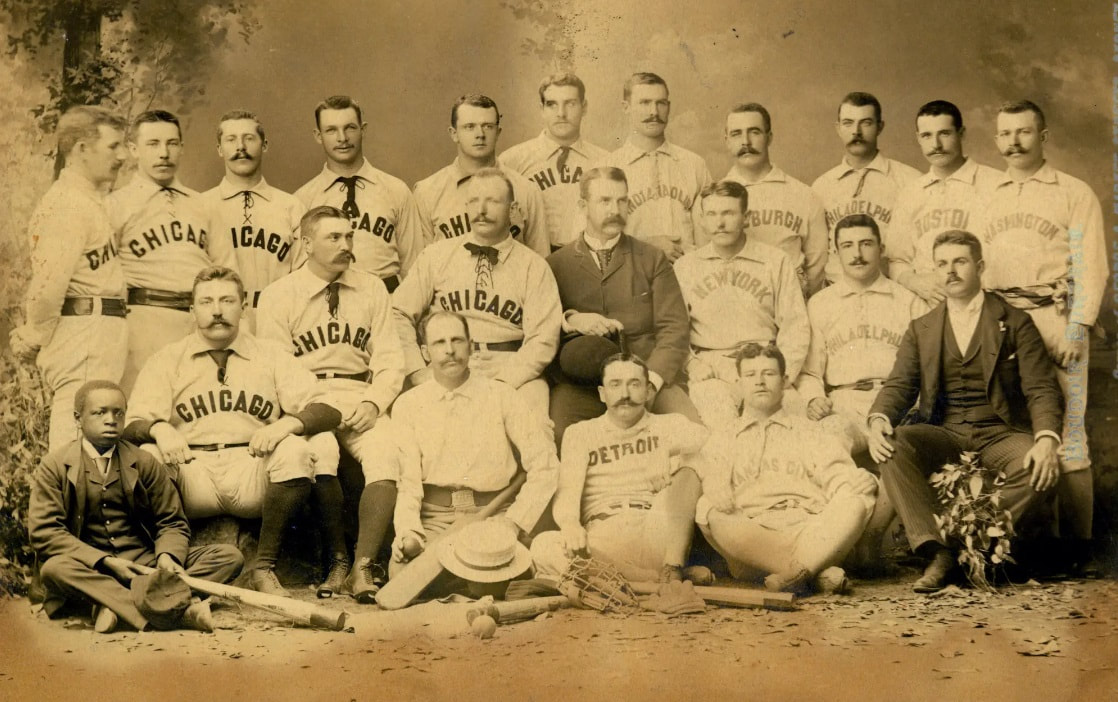

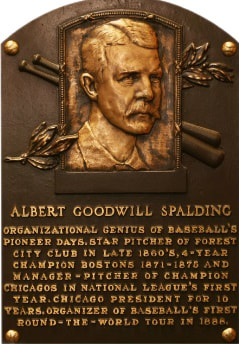

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/poster-from-1888-89-spalding-australian-baseball-tour-part-of-heritage-auctions-sale/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed