www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/ruth-signed-book-includes-babe-endorsed-check-used-to-pay-for-it/

|

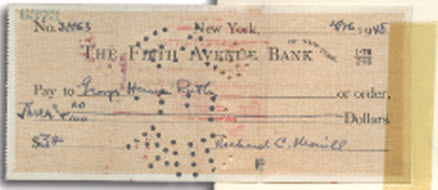

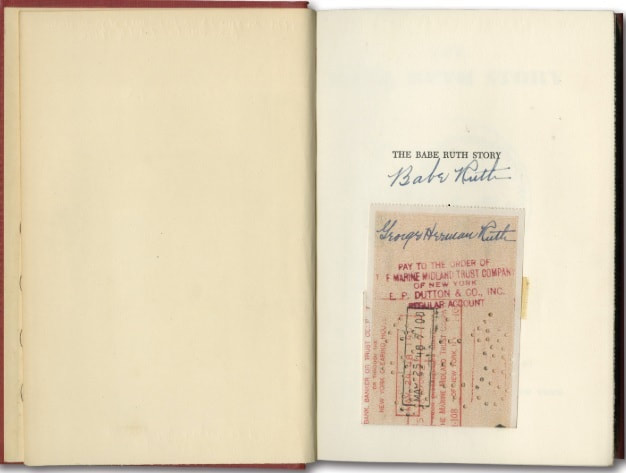

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an autographed Babe Ruth book that includes a cnaceled check endorsed by the Bebe: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/ruth-signed-book-includes-babe-endorsed-check-used-to-pay-for-it/

0 Comments

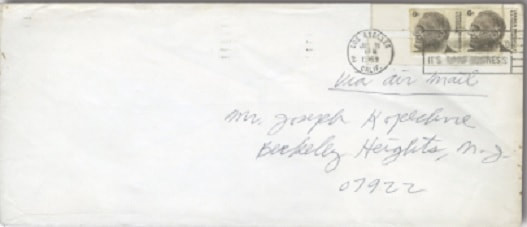

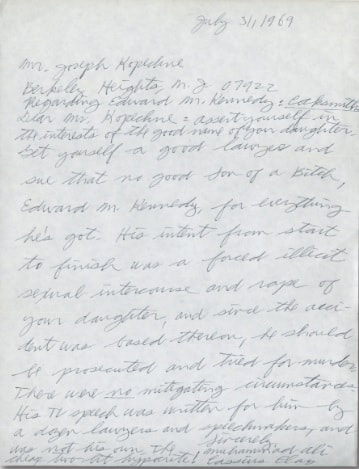

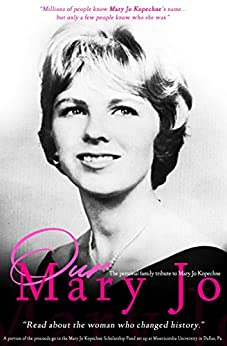

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an item for bid at SCP Auctions Spring Premier Auction: an emotionally charged letter written by Muhammad Ali to the family of Mary Jo Kopechne, the woman who died in the Chappaquiddick incident in July 1969:

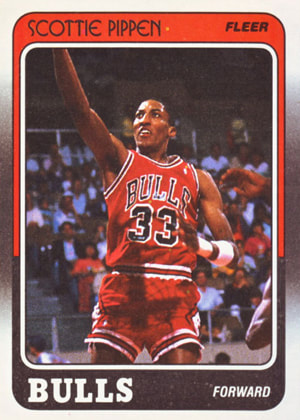

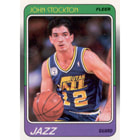

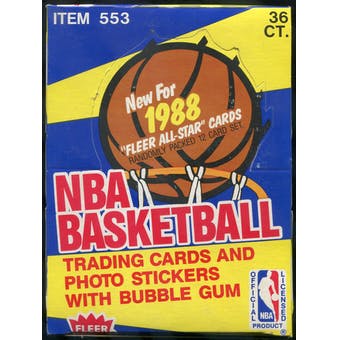

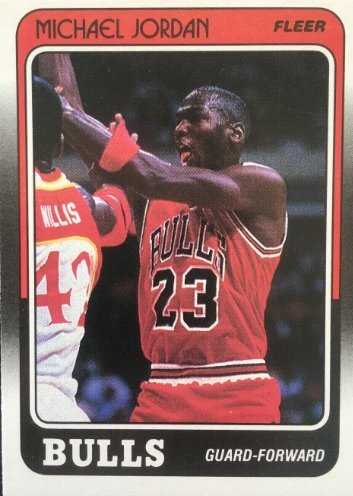

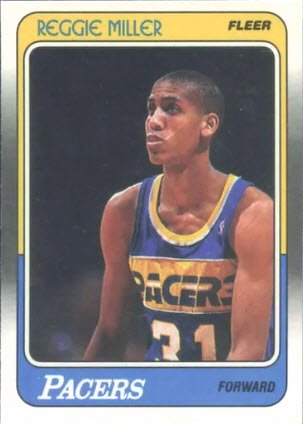

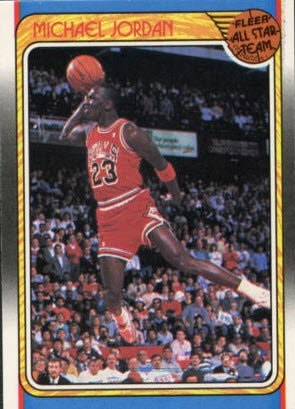

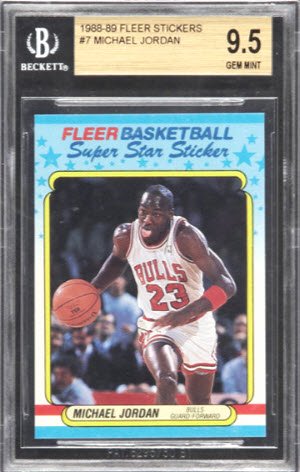

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/muhammad-alis-emotional-letter-to-mary-jo-kopechnes-family-up-for-bid-at-scp-auctions/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily, looking back at the 1988-89 Fleer basketball set, loaded with stars and rookies:

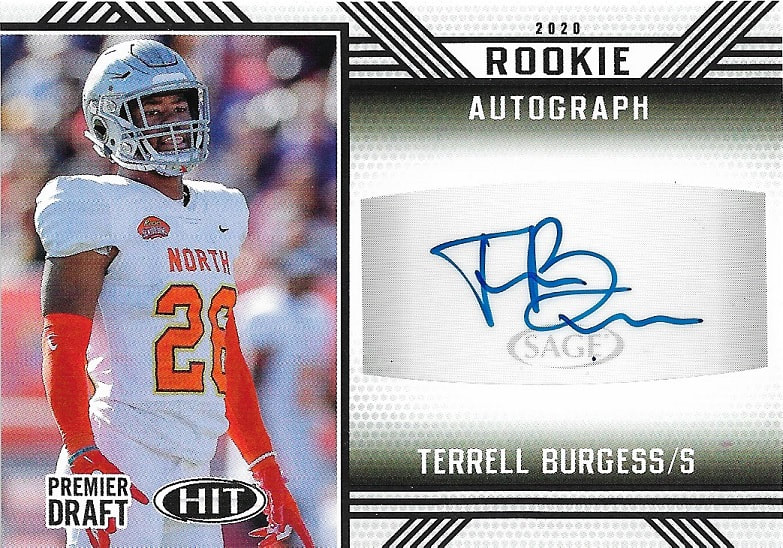

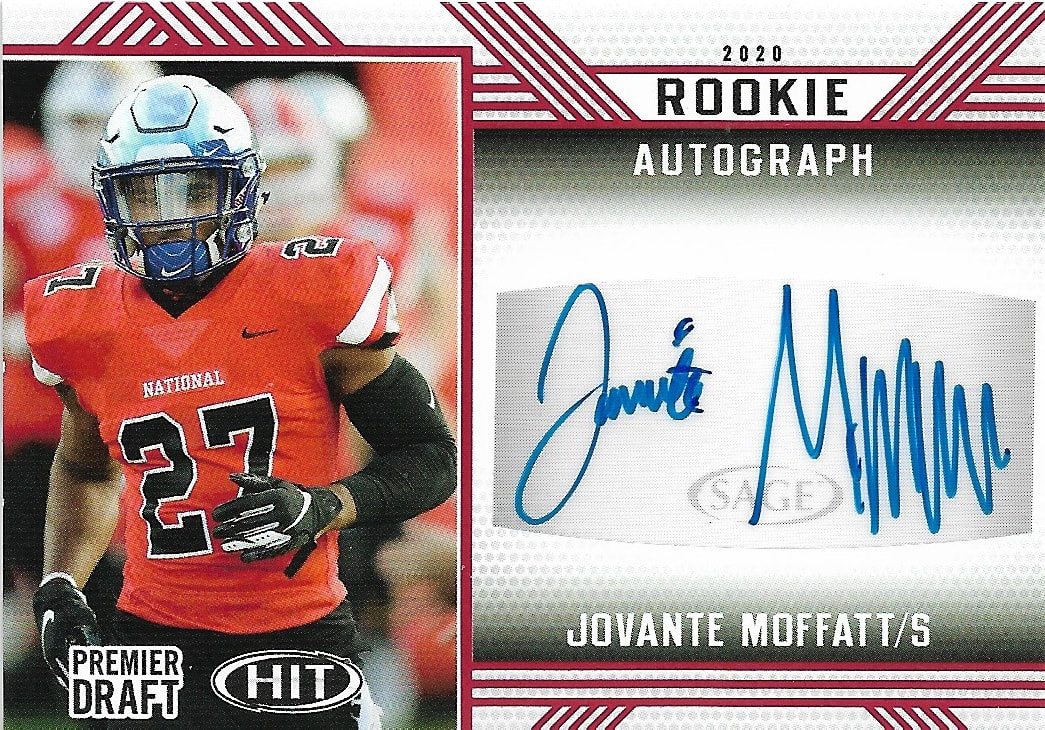

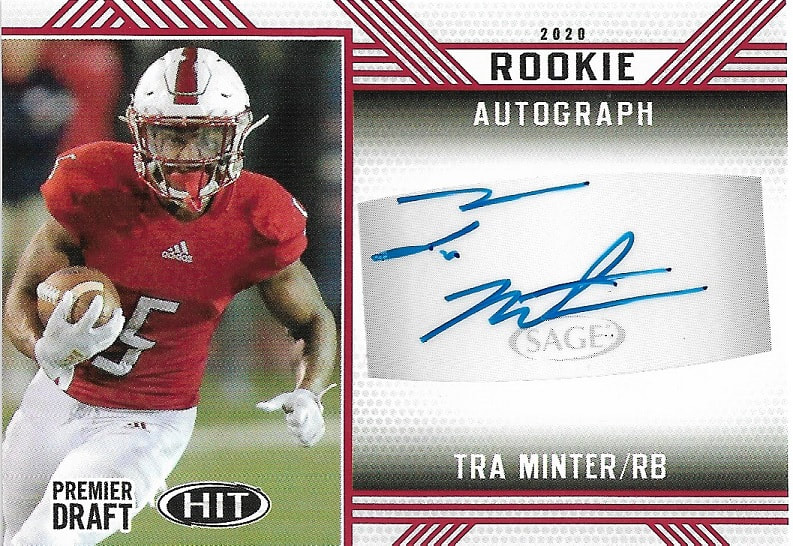

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/waxing-nostaglic-1988-89-fleer-basketball-loaded-with-key-rookies-stars/ I’ve been enjoying articles about the upcoming NFL draft. There is not much else to watch sports-wise, so speculating on what players teams will draft is a nice diversion. The same goes for football cards. Sage Hit Premier Draft 2020 Low Series football cards allow collectors to see some of the possible names who will be on the virtual draft board next week. Granted, Sage does not carry any league or team licensing, so all logos are airbrushed from card images. Still, it’s nice to pull a Joe Burrow or Tua Tagovailoa card.  What’s nice about the Sage set is that there are only 50 cards in the base set, and a blaster box can almost cover it. In fact, the blaster I bought had 48 of the 50 base cards. Why I didn’t get Florida Atlantic’s Harrison Bryant (card No. 15) and Alabama’s Jerry Jeudy (No. 48) remains a mystery. A blaster box contains, on average, 60 base cards, eight silver parallels and three autographs. So, 12 of the base cards I pulled were duplicates. The first 37 cards in the set are straightforward rookie cards. The next five are called Five-Star are feature Wisconsin running back Jonathan Taylor. The remaining eight cards are part of a subset called Next Level. The blaster box I bought had six packs, with 12 cards in five of them. The sixth pack contained all three autographs and eight silver parallels that included a silver Next Level card of Burrow.  The design of the cards is simple, with an action shot of the player framed by a zebra-stripe kind of border. The Hit logo is in the upper left-hand corner of the card front, and the player’s name is sideways, running down the left-hand side for the first 37 cards. The card backs have a four-line biography with the lead-in headline, “Here’s Something.” The player’s name, position and vital statistics are placed near the top of the card, while statistical information is situated beneath the player biography. The Five-Star subset features five different shots of Taylor during his football career, from a New Jersey prep star at Salem High School through his marvelous career at Wisconsin. The Next Level cards feature a photo of the player on the front and bullet-item highlights on the back. The autographs are on stickers. The cards have a horizontal design, with an action shot of the player taking up about 40% of the left side of the card front. The right side contains ample space for an autograph.

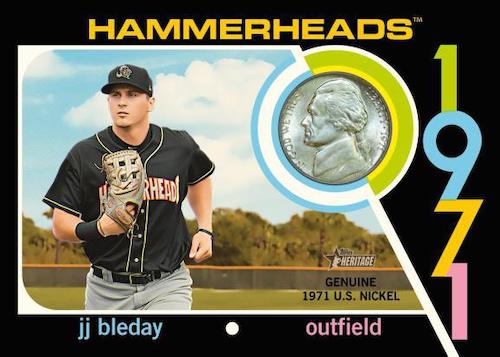

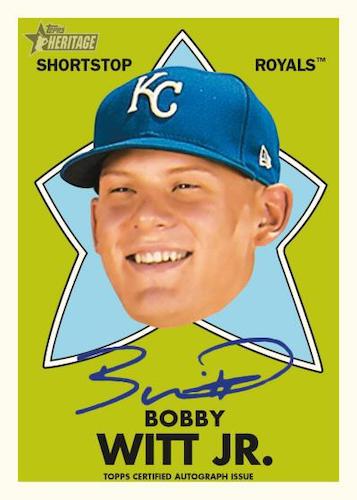

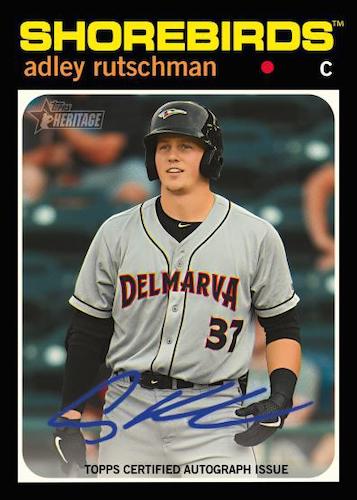

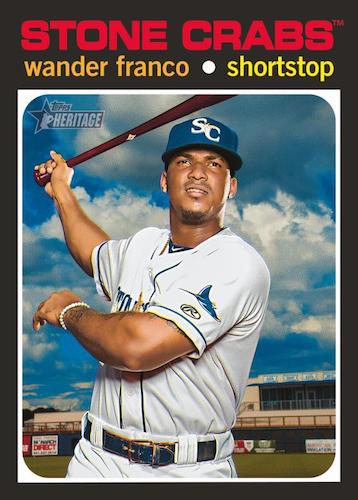

The autograph cards I pulled were of Jovante Moffatt, a safety out of Middle Tennessee State; Terrell Burgess, a safety out of Utah; and Tra Minter, a running back out of South Alabama. Sage Hit Premier Draft 2020 Low Series football cards are a nice way to scratch that itch for the NFL draft. With so few sports options available, this is an easy set to collect. Will any of the players have fruitful NFL careers? It’s hard to say. But for now, it’s fun to speculate. Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily previewing the 2020 Topps Heritage Minor League Baseball:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2020-topps-heritage-minor-league-brings-1971-to-the-farm/

Baseball is more than a sport in Cuba. It is a passion.

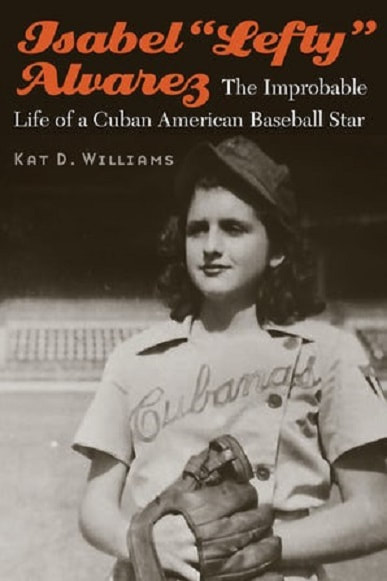

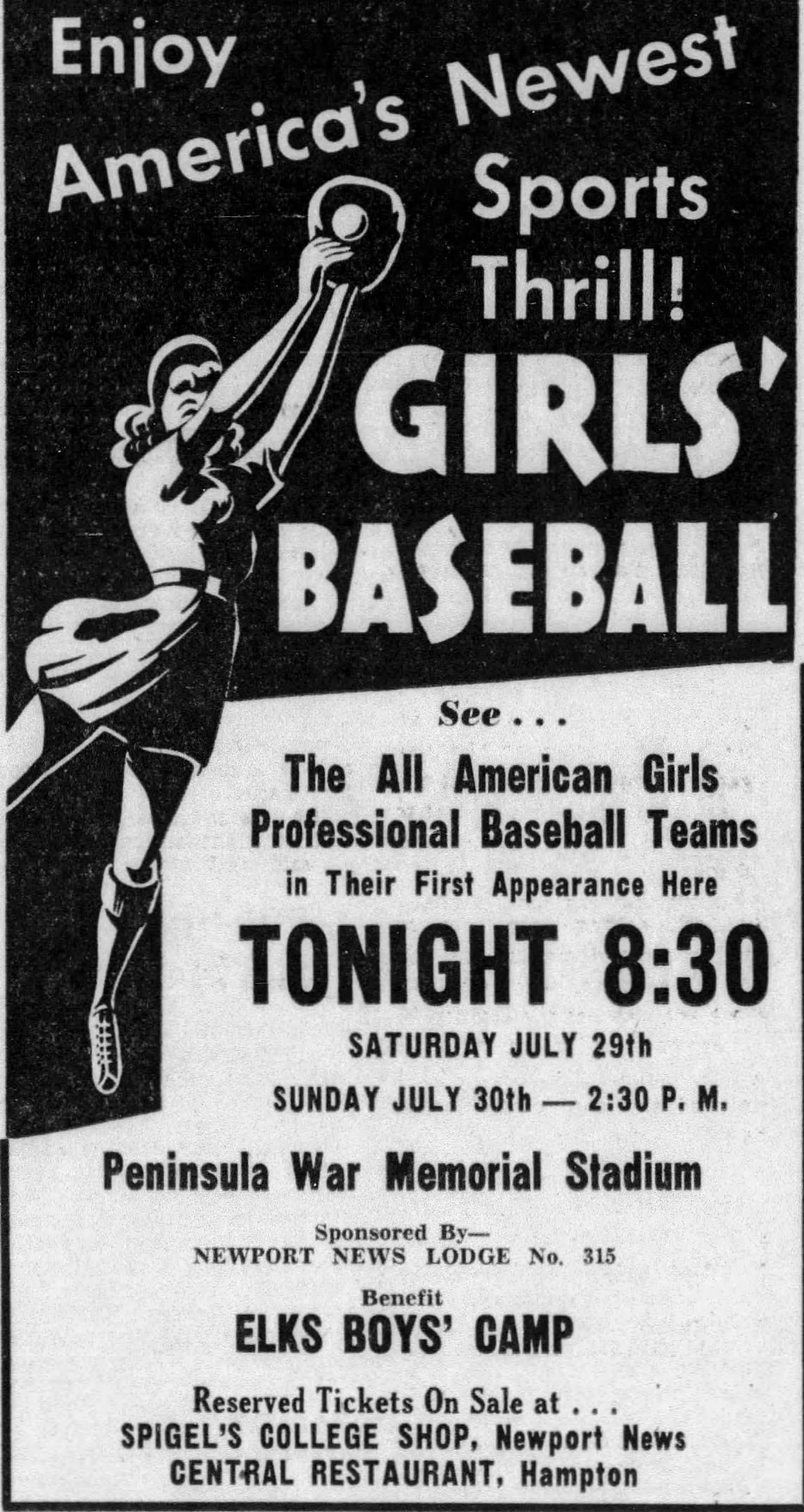

Plenty of books have been written about baseball on the Caribbean island that sits south of Florida, but all of them concentrate on men. You can roll the good works off your tongue: Roberto González Echevarría’s 1999 book, The Pride of Havana; Peter C. Bjarkman’s A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006, in 2007; [RD1] and César Brioso’s award-winning 2019 book, Last Seasons in Havana. Kat D. Williams has taken a different angle, concentrating on women’s baseball, and specifically, the career of Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez. Williams, a professor of American history at Marshall University, has written a warm, sentimental biography about a woman who first came to the United States from Cuba as a teenager. In Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez: The Improbable Life of a Cuban American Baseball Star (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 161 pages, release date: May 1), Williams traces Alvarez’s professional career, which included a stint in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

Williams employs a different technique to tell Alvarez’s life story, a concept she calls “sport-identity.”

Alvarez, Williams argues, relied on the identity she created during her athletic days “to survive a difficult life.” Indeed, Alvarez would have to rely on the “sport part of myself” many times in her career, Williams writes. Alvarez’s confidence on the mound evaporated away from the diamond; after her baseball career ended, she battled alcoholism and depression. But baseball defined her life and gave her something to live for in her adopted country. The 1992 movie, “A League of Their Own,” introduced a new generation of Americans to the AAGPBL. Marvelously directed by Penny Marshall and featuring stars like Tom Hanks, Geena Davis, Lori Petty, Madonna and Rosie O’Donnell, the film was fun to watch. The actual league is what motivated Alvarez to stay in the United States. “The only reason I am an American citizen is because of baseball,” Alvarez told The Associated Press in 1996.

Williams is board president of the International Women’s Baseball Center. She also wrote 2017’s The All-American Girls after the AAGPBL: How Playing Pro Ball Shaped Their Lives. For her latest book, Williams draws plenty of material from her interviews with Alvarez, who she became friends with. While Alvarez’s memory was beginning to fade, her ebullience would still rise to the surface with her “Holy, cow!” exclamations. She was known as the “little rascal of El Cerro,” the Havana neighborhood where she grew up. But boy, did Alvarez grow up fast. She was the product of an overprotective mother who wanted her to rise into a middle-class lifestyle and an indifferent father who was a police officer for Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Her mother pushed Lefty into several areas, hoping she could achieve that middle-class status. Virtudes Alvarez nevertheless did not mind when her daughter wanted to stay out of school and limiting Lefty’s education proved to be a hindrance later in life. Alvarez’s mother first entered Lefty into beauty pageants. The unhappy 13-year-old still managed to finish second in one of her contests, but she was “miserable playing like I was a lady, sitting around looking pretty.” Alvarez also appeared to be the victim of some sexual inappropriateness. An audition with a radio station worker turned into a one-sided groping session. At home, when Lefty’s mother insisted she lie next to her and sleep facing her, Alvarez’s brother accused them of being lesbians. Alvarez’s brother was no saint, either, asking his younger sister to step into the shower with him. It’s a disturbing youth, but Alvarez got her break when her mother decided Lefty should become an athlete. And baseball was her way out of Cuba. Poorly educated and not knowing the language, the adjustment for Alvarez was tough — on and off the field. “Playing baseball was both fun and a struggle,” Williams writes. At the end of every AAGPBL season, Alvarez would return to Cuba, where her mother tried to keep her safe “from neighbors or potential boyfriends,” Alvarez told Williams. “It was like they were there to view me, like I was a doll or something,” Alvarez said. “I think my mother wanted people to see how well I was doing, that I was successful.” It appears Alvarez’s mother was not too successful at keeping the boys away, as U.S. newspaper articles implied in 1950. “What happens when a Cuban girl wants to play baseball and her Cuban boyfriend says no?” the Newport News Daily Press reported in July 1950. “Apparently, she does the same thing that happens right here in the U.S. She plays baseball.” An article in a similar vein that same week, by Ed Nichols of The Daily Times in Salisbury, Maryland, was more explicit when Ramon Antonio de la Cruz, a university student in Havana, told Alvarez to make a choice: “Isabel puts it this way. ‘Number one is baseball; number two is Ramon.’” Considering Alvarez’s command of English was limited, the story was probably told either through one of her Cuban teammates or through the imagination of the sportswriters. Regardless, Alvarez attracted attention, whether she was playing for the Chicago Colleens, the Fort Wayne Daisies, the Battle Creek Belles or the Kalamazoo Lassies.  Nancy Blee and her family took in Lefty during the 1952 season. Nancy Blee and her family took in Lefty during the 1952 season.

Williams gets Alvarez to talk about the Blee family of Fort Wayne, Indiana, who took in the young pitcher during the 1952 season when Lefty did not have a contract to play ball. Nancy Blee (at left), a year younger than Alvarez, met the pitcher when she helped Lefty find her lost wallet at a Fort Wayne park. The Blee family sponsored Alvarez and helped her become a U.S. citizen by the late 1950s.

“It was the support of the Blee family and Lefty’s memory of her ‘sport self’ that carried her through that year,” Williams writes. Alvarez’s career ended when she injured her knee during a 1954 game. She remained in Fort Wayne but Williams notes that the demise of the AAGPBL, the departure of her Cuban teammates, “the structure and built-in sense of family and community” made life difficult when she could no longer play the game. However, Alvarez regained her sport-identity somewhat when she began playing in Fort Wayne softball leagues. Despite her personal battles, she had a satisfying career at General Electric before retiring in 1999. During the 1980s, Alvarez began reconnecting with former members of the AAGPBL, who did not know her “until I opened my mouth.” “That crazy Cuban” had found her sport-identity once again.

Williams’ research covers a good slice of Cuban history and the history of the AAGPBL. Appendixes include Alvarez’s known statistics and a timeline of women’s baseball, beginning with the formation of a team at Vassar College in 1866.

Historians will enjoy the stories about women’s baseball and the turbulent times in Cuba under Batista, which eventually came under the thumb of another dictator, Fidel Castro. Williams writes in a sentimental tone, but it works. One cannot help but root for the dark-haired, left-handed 15-year-old pitcher, who came to the United States with hardly any education and no command of the language. “Lefty endured, and despite it all she was able to have a life that made her proud,” Williams writes. From that perspective, Lefty Alvarez is truly in a league of her own.

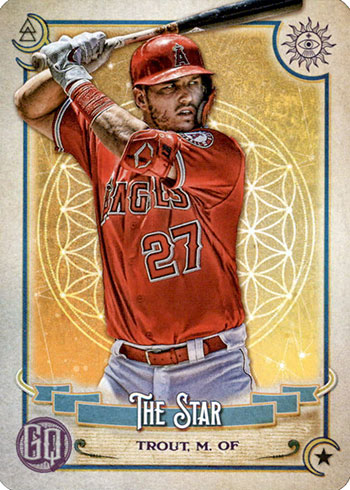

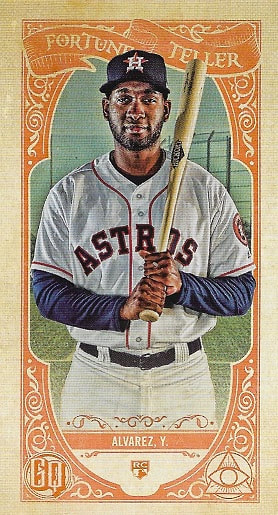

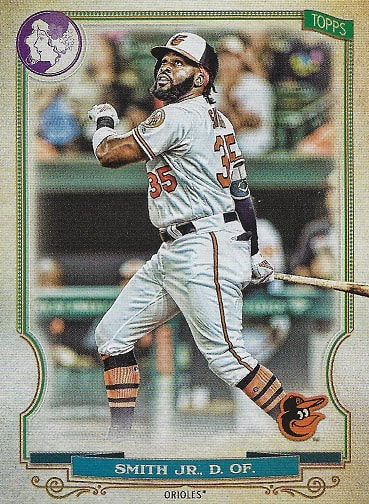

One of the insert cards in the Gypsy Queen baseball set is Fortune Teller, where a player is featured and a bold prediction about the upcoming season is made. Topps must be kicking itself, given what has happened: The major league baseball season was delayed because of the coronavirus pandemic, an event no one could have foreseen. Now that would have been quite a prediction. Naturally, it is not Topps’ fault, as the 2020 Gypsy Queen set was already printed and ready to go last month. The new set will still be pleasing to collectors. Gypsy Queen follows the same format it has since Topps revived the old tobacco card set in 2011. There is a 300-card base set, along with 20 short-printed cards. There are also variations and parallels. I bought a blaster box, so there are seven packs with six cards per pack. There is an additional five-card pack of green parallels. I pulled 38 base cards, one short-printed card (Ted Williams) and one logo swap card of Dwight Smith Jr. The front of the card sports an artistic-looking action shot of the player, with the background shown in soft focus. The Topps “GQ” logo is located in the front left corner of the card, while the team logo is situated in the lower right-hand corner. The player’s name is shown beneath the action shot in a ribbon-like display, with his last name and first initial. Meanwhile, the team name is shown beneath the ribbon in very small print. The logo swap is interesting, as the GQ logo is switched out for a purple-and-white stencil drawing of a woman. The logo swaps occur once every 41 packs, according to Topps. The card backs feature a five- or six-line biography of the player. The three major components of the card back are in a light green tint, while the color framing those boxes are a light beige that also contains a green tint in the lower left-hand side of the card. The team logo sits atop the player’s name at the top of the card. I pulled two inserts from the blaster box I bought. One was a Fortune Teller card of Yordan Alvarez, which predicted the young outfielder/designated hitter would knock in 101 runs to top Jeff Bagwell’s two-year team total for a Houston player’s first two seasons (178). That looks unlikely right now. The second insert was a Tarot of the Diamond card of Mike Trout, labeled “The Star.” The GQ logo is situated in the bottom left-hand corner of the card, with tarot symbols occupying the other three corners.

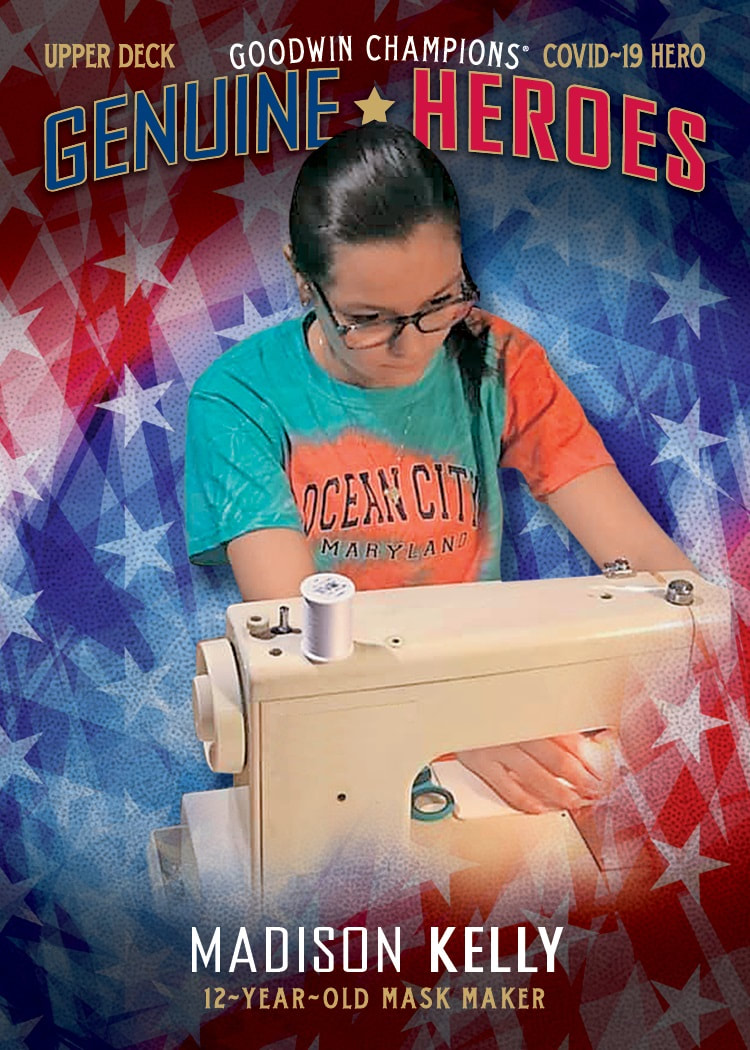

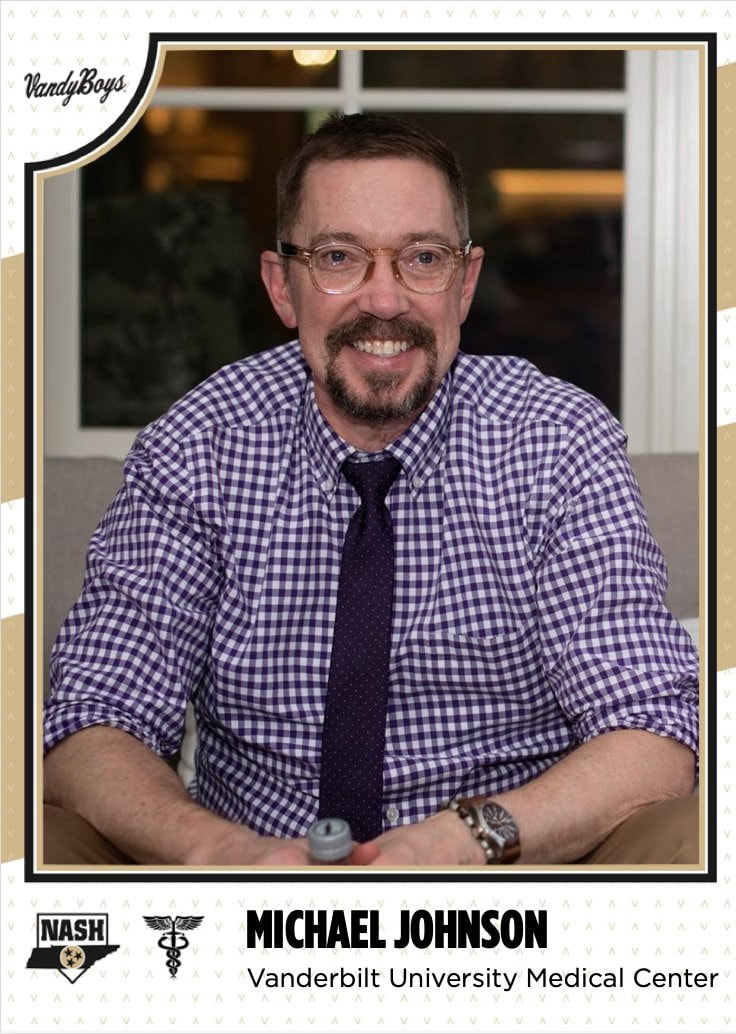

The Gypsy Queen set is an interesting one, with fewer inserts to chase than the Allen & Ginter set, which is comparable in its retro feel. There are autographs and memorabilia cards, but those are more likely to be found in hobby boxes. The other main difference besides the inserts is that Gypsy Queen stays focused on baseball, while the A&G set hops around between sports, history, pop culture and politics. From that standpoint, Gypsy Queen is much easier to collect.  With no live football on television or in stadiums because of the coronavirus pandemic, the next best thing — other than watching old reruns — is collecting football cards. But let’s be honest. You can only watch so many reruns of Super Bowl VII, no matter how delicious the outcome was. Perfect season times 100. I think I can call every play in my sleep now. So, I ventured to Target and bought a blaster box of 2020 Leaf Draft football, which was released last month but finally made it to my area this week. The idea behind this set is fun: Put together the most promising college football prospects who have a chance to be drafted in the upcoming NFL draft. This year’s draft, even though it will be held in a virtual format, will still be intriguing. The 2020 Leaf Draft blaster box contains 20 packs, with five cards per pack. There are two autograph cards in every retail box. At $19.99, this works out to just under a dollar a pack. It’s hard to get those kinds of deals anymore.  The set consists of 100 cards. The first 60 of them are designated as commons. Cards 61 to 75 are All-American cards, No. 76 through 90 are Touchdown Kings, while 91 through 100 are Flashback cards. Parallels cards are distinguishable by gold components. The box I opened had 47 commons, 13 All-Americans, 13 Touchdown Kings and seven Flashbacks. And, two autograph cards that were separate from the packs. There were 20 parallels in the box I opened: 14 commons, two All-Americans, two Touchdown Kings and two Flashbacks. Some of the packs (I counted at least two) had three Touchdown Kings cards in them and two base common cards. The design is clean for the cards. The player photographs in the commons are black and white, which gives the cards a nice retro feel. The Leaf logo is in the upper left-hand corner of the card front, while a Leaf rookie card logo is nestled in the upper right.  It seemed a little silly to have a rookie card designation on these cards; after all, except for Flashback cards, many — but not all— of the players depicted are likely to be NFL rookies. I can see Leaf’s point to a certain extent, but it seemed unnecessary. Because Leaf does not have licensing rights, all of the team logos are airbrushed out of the cards. In the fine print on the card back, Leaf notes that the card “is solely licensed by the depicted player.” It goes on to remind the consumer that the card has not been endorsed by that player’s university, college or any licensing agency. The card backs for the commons contain a seven-line mini-biography of the player, along with vital statistics like height, weight and position. There are also biographies for the other card subsets. I particularly enjoyed the Flashback cards, which contain cards of NFL legends. The ones I pulled were Jerry Rice, Paul Hornung, Dick Butkus, Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, Deion Sanders and Aaron Rodgers.  As promised, there were two autograph cards in the blaster box I bought. Both were sticker autographs. The first was of former Auburn offensive tackle Prince Tega Wanogho, who signed with a giant “P’ and what looks to be a line stroke that could form a “T” on the same alphabetical character. There is a period to the right. I knew there was a paper goods shortage, but I didn’t realize there was a shortage of ink. The second signature belonged to former Oregon tight end Jake Breeland. It’s sloppy, but at least he signed his first and last names. Overall, this is a nice product that is inexpensive and seemingly easy to complete. Even the parallels appear easy to complete, given the amount placed in each blaster box. It’s a nice way to spend time looking at cards and wondering which of these young football stars will get drafted and whether any of them will become stars. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Upper Deck's Genuine Heroes card program, which honors people fighting on the front lines against the coronavirus; and Tim Corbin, the Vanderbilt University baseball coach who came up with a similar idea to honor people in the Middle Tennessee area:

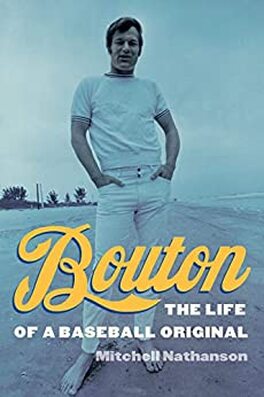

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/upper-deck-vanderbilt-baseball-coach-honor-heroes-fighting-against-coronavirus/  I revered Ball Four as a kid. I first read it as a 13-year-old and was mesmerized. A baseball book had never been so honest, so earthy, so profane. Naturally, I loved it. My father claimed (incorrectly) it was the only book I ever read. My dog-eared pages of Ball Four, Jim Bouton’s diary of the 1969 major league season, would have made that assumption perfectly logical. Bouton was a journeyman pitcher when he began taking notes in 1969, hanging on, as he wrote at the time, by his fingernails. As a knuckleball pitcher, that was the perfect analogy. Bouton won 21 had games in 1963 and 18 the following year, plus a pair of World Series games, but by 1969 he was struggling to latch on with a major league team. He would finish his career with a 62-63 record, but it was his observations as a writer that would set Bouton apart. The furor generated by Ball Four was immense, and it solidified Bouton’s reputation as a maverick, a renegade, a darling of the late 1960s counterculture and a player-turned-author who pulled no punches. A half-century later, it all seems so tame in retrospect. Did we really care that Mickey Mantle went up to pinch-hit in a hungover haze? Of course not, since the Mick hit a home run, squinting out at the stands and muttering, “Those people don’t know how tough that really was.” But it was a big deal then. Sports heroes were portrayed as Jack Armstrong types, and Bouton tore away the curtain to reveal the reality of it all. A biography about Bouton? Could one be written in the same spirit as Ball Four — funny, perceptive and thoughtful? Mitchell Nathanson did so, and more. In Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $34.95 407 pages), Nathanson, a professor of law at the Villanova University School of Law, presents an honest, balanced look at Bouton, who died last July at the age of 80. The book has a May 1 release date. Nathanson presents the humorous and inventive side of Bouton. He also reveals the self-centered, shoot-from-the-hip persona Bouton’s former roommate in Houston, Norm Miller, recognized as being similar to the knuckleball, “in that he had difficulty controlling it,” Nathanson writes. When Nathanson broached the idea of a biography, Bouton and his wife, Paula Kurman, gave their blessing but insisted the author explore all angles of his life and waived any editorial control. Most of all, they did not want a “puff piece,” Nathanson writes.  They didn’t get one. Nathanson, who has written a biography about Dick Allen (God Almighty Hisself), the Philadelphia Phillies (The Fall of the 1977 Philadelphia Phillies) and A People’s History of Baseball, gives Bouton his due but also points out his flaws. Bouton gets high marks for his courage in writing Ball Four, his willingness to mingle with the younger generation of sportswriters — derisively nicknamed chipmunks — his fearlessness in taking political stands when baseball players mostly remained mute on the subjects of Vietnam and civil rights, his generosity with young fans and his tenacity to succeed. That tenaciousness also gets him low marks, as Bouton insisted throughout his life that he had “to be true to myself.” If that meant not reading scores during his newscasts or antagonizing his fellow broadcasters, so be it. If it meant having extramarital affairs while his first wife, Bobbie, was at home with their three children, it was going to happen. If it meant removing the name of Leonard Shecter from the cover of Ball Four when anniversary editions of the book were released so the book looked “looked cleaner,” that was all right, too. Shecter, a sportswriter for the New York Post and later the sports editor for Look magazine, collaborated with Bouton on Ball Four. Shecter, who died in 1974, used his editing skills and ability to push the pitcher to provide more depth and insight to set it apart from other sports books. Certainly, Jim Brosnan’s two books — The Long Season (1960) and Pennant Race (1962) — along with Jerry Kramer’s diary of the 1967 NFL season, Instant Replay, and Bill Freehan’s 1970 book, Behind the Mask, opened the door a crack for sports fans eager to get an inside look. But Ball Four kicked the door down and was more than a “tell-some” book. Amphetamine use (they were called “greenies” back then), voyeurism and rough clubhouse humor and pranks were covered in detail. Friction between teammates, the pettiness of management and the unintentional humor imparted by Seattle Pilots manager Joe Schultz — who directed a crew of rejects and misfits — was a gold mine of material for Bouton. In one of his few moments of hyperbole, Nathanson calls the Bouton-Shecter collaboration “the sportswriting equivalent of Lennon and McCartney.” However, Nathanson’s explanation of the writing process that shaped Ball Four could be called a hard day’s night — and more. Nathanson recounts Bouton and Shecter meeting in the sportswriter’s non-air-conditioned apartment in Manhattan to review the pitcher’s 15 cassette tapes and 978 scraps of notes, shaping them into a cohesive narrative. “(Shecter) had a hot, sticky apartment,” Bouton told Nathanson. “And he’d say, ‘Take your pants off, Bouton. We’ve got a long night ahead of us.’” “And there’d they be,” Nathanson writes. “Two men, in their underwear, shaping the raw material that in less than a year’s time would become Ball Four.” Nathanson gives the reader a literary locker room view of the process that led to Ball Four. He describes how Bouton and Shecter had to fight to keep passages the publishers deemed legally sensitive. World Publishing’s lawyers targeted 42 items as “potential legal land mines.” Bouton and Shecter only acquiesced on five of them. Nathanson also examines the argument detractors used when Ball Four was released — that it was Shecter, not Bouton, who was the writing wizard. And, that Bouton was taking notes on the sly, which is he was not. Several players are quoted in Ball Four as saying, “Hey, put that in your book.” The note-taking did not surprise the players, then. Rather, “it was the frankness of the book that startled them,” Nathanson writes. “So much so that when asked about it, they claimed ignorance of the entire thing.” As to the first assertion, Nathanson argues Shecter helped shape the prose but did not create it. Nathanson notes “it was Bouton’s ear for language that causes Ball Four to sing.” Those criticisms came, if not overtly, then insinuated, by some of Shecter’s contemporaries. Of note, New York Daily News columnist Dick Young, a groundbreaking sportswriter who was the first to go into the locker room and talk to players when he covered the Brooklyn Dodgers during the 1950s, was upset by Ball Four. Young went so far as to label Bouton “a social leper,” and inadvertently gave Bouton the quote he would use to title his follow-up book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally. It was professional jealousy. “In truth, all of Young’s bluster was cover for his pique that the man who considered himself the game’s ultimate inside was scooped,” Nathanson writes. The Ball Four stories are enough to carry the book, but Nathanson realized there was life before and after the bestseller list. He delves into Bouton’s childhood and his early days with the New York Yankees. He interviewed the kids who began his fan club in the mid-1960s and wrote a newsletter, “All About Bouton,” and his relationship with the “chipmunk” writers. “The Chipmunks saw Bouton as their Sinatra, their Merry Prankster,” Nathanson writes. “An increasingly rogue spirit with a singular style.” That style bought Bouton credibility post-baseball when he became a sportscaster for WABC and, later, WCBS. Fellow sportscaster Sal Marchiano, who was constantly at odds with Bouton, told Nathanson that “he was more interested in promoting himself. That’s the bottom line, to me, about his broadcasting career. It was about him.” Don’t just take it from an angry former colleague. Joan Walden Maurer, a professional ice skater during the 1950s who lived in the same area of New Jersey as Bouton two decades later, was equally blunt. “Jim Bouton? Yeah, he stands in traffic and asks if anyone wants his autograph,” Maurer told me in 1979 when I visited her daughter, future CNBC Radio journalist Chris Maurer, sharpening her blades at the former athlete’s expense. Behind the swagger and ego, there was a gentler side to Bouton, Nathanson writes. He goes into greater detail about the 4-year-old Korean boy Bouton and his first wife, Bobbie, adopted. Kyong Jo, who later Americanized his name to David, had trouble adjusting when he first entered the Bouton household, angry that his birth mother had abandoned him and disgruntled because he believed his new family did not live in America. The child said the family would take him to America, where he would go into stores and see aisles of toys, clothes and electronics. But when the family got in the car to go home, Kyong Jo said that place “wasn’t America at all.” Slowly, painfully, the boy adapted to American life. It’s a tender story that is rarely told about Bouton. There was the tragic death of Bouton’s daughter, Laurie, who was involved in an automobile accident in 1997. And there was his son Michael’s op-ed to The New York Times in 1998, asking the Yankees to invite him to Old Timers Day. Along with the brass, there was a lot of pathos, and Nathanson captures it well. Bouton remained a tinkerer and a hustler to the end. He hit it big with former minor league teammate Rob Nelson when they developed Big League Chew, which was bubblegum in a pouch made to look like chewing tobacco. It was an immediate hit. “He was always on the lookout for the next big thing,” Nathanson writes. “Always in search of a new and different way to bring in income and have fun while doing it.” Bouton is bolstered by Nathanson’s research, as he used newspaper and magazine articles to provide background. He also did extensive interviews with Bouton, his two brothers, his two wives —Bobbie Bouton-Goldberg and Paula Kurman — and Jill Baer, who had an affair with Bouton. Nathanson also talked with former teammates like Gary Bell, Tommy Davis, Larry Dierker, Norm Miller, Fritz Peterson and Mike Marshall (via email). He also spoke with sports journalists including Ira Berkow, Peter Golenbock, Keith Olbermann, Bill Shonely, Larry Merchant and Jeremy Schaap. Bouton is a book that deserves space next to Ball Four on the bookshelf. Nathanson has done a thorough job of presenting the life of a complex man who changed the game of baseball, not by what he did on the field, but what he observed on the field, in the clubhouse and on the road. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the outcome of a trademark infringement lawsuit filed in December by Panini America against Pennsylvania resident Jamie Nucero:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/panini-america-gets-injuction-in-trademark-case-against-nucero/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed