Plenty of books have been written about baseball on the Caribbean island that sits south of Florida, but all of them concentrate on men.

You can roll the good works off your tongue: Roberto González Echevarría’s 1999 book, The Pride of Havana; Peter C. Bjarkman’s A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006, in 2007; [RD1] and César Brioso’s award-winning 2019 book, Last Seasons in Havana.

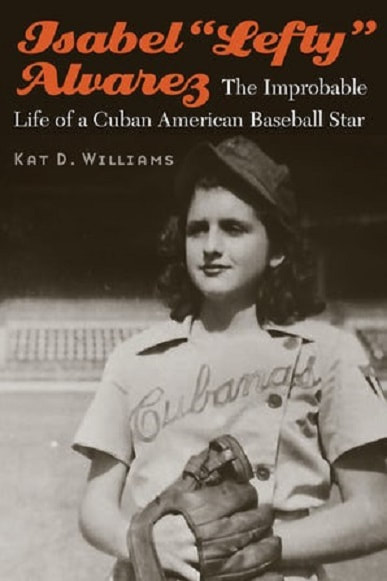

Kat D. Williams has taken a different angle, concentrating on women’s baseball, and specifically, the career of Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez.

Williams, a professor of American history at Marshall University, has written a warm, sentimental biography about a woman who first came to the United States from Cuba as a teenager. In Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez: The Improbable Life of a Cuban American Baseball Star (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 161 pages, release date: May 1), Williams traces Alvarez’s professional career, which included a stint in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

Alvarez, Williams argues, relied on the identity she created during her athletic days “to survive a difficult life.”

Indeed, Alvarez would have to rely on the “sport part of myself” many times in her career, Williams writes. Alvarez’s confidence on the mound evaporated away from the diamond; after her baseball career ended, she battled alcoholism and depression. But baseball defined her life and gave her something to live for in her adopted country.

The 1992 movie, “A League of Their Own,” introduced a new generation of Americans to the AAGPBL. Marvelously directed by Penny Marshall and featuring stars like Tom Hanks, Geena Davis, Lori Petty, Madonna and Rosie O’Donnell, the film was fun to watch. The actual league is what motivated Alvarez to stay in the United States.

“The only reason I am an American citizen is because of baseball,” Alvarez told The Associated Press in 1996.

For her latest book, Williams draws plenty of material from her interviews with Alvarez, who she became friends with. While Alvarez’s memory was beginning to fade, her ebullience would still rise to the surface with her “Holy, cow!” exclamations. She was known as the “little rascal of El Cerro,” the Havana neighborhood where she grew up.

But boy, did Alvarez grow up fast. She was the product of an overprotective mother who wanted her to rise into a middle-class lifestyle and an indifferent father who was a police officer for Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Her mother pushed Lefty into several areas, hoping she could achieve that middle-class status. Virtudes Alvarez nevertheless did not mind when her daughter wanted to stay out of school and limiting Lefty’s education proved to be a hindrance later in life.

Alvarez’s mother first entered Lefty into beauty pageants. The unhappy 13-year-old still managed to finish second in one of her contests, but she was “miserable playing like I was a lady, sitting around looking pretty.”

Alvarez also appeared to be the victim of some sexual inappropriateness. An audition with a radio station worker turned into a one-sided groping session. At home, when Lefty’s mother insisted she lie next to her and sleep facing her, Alvarez’s brother accused them of being lesbians. Alvarez’s brother was no saint, either, asking his younger sister to step into the shower with him.

It’s a disturbing youth, but Alvarez got her break when her mother decided Lefty should become an athlete. And baseball was her way out of Cuba. Poorly educated and not knowing the language, the adjustment for Alvarez was tough — on and off the field.

“Playing baseball was both fun and a struggle,” Williams writes.

At the end of every AAGPBL season, Alvarez would return to Cuba, where her mother tried to keep her safe “from neighbors or potential boyfriends,” Alvarez told Williams.

“It was like they were there to view me, like I was a doll or something,” Alvarez said. “I think my mother wanted people to see how well I was doing, that I was successful.”

It appears Alvarez’s mother was not too successful at keeping the boys away, as U.S. newspaper articles implied in 1950.

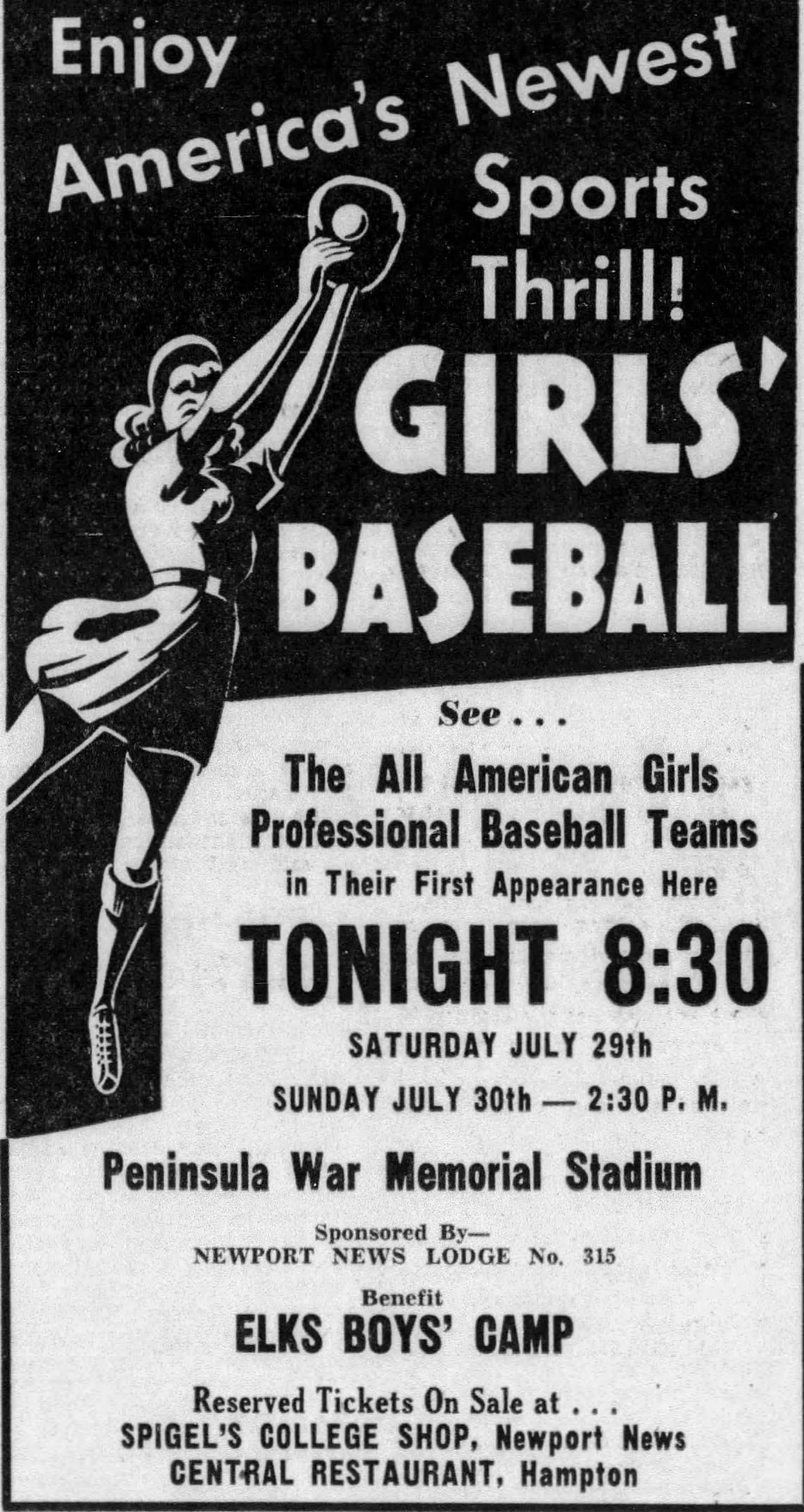

“What happens when a Cuban girl wants to play baseball and her Cuban boyfriend says no?” the Newport News Daily Press reported in July 1950. “Apparently, she does the same thing that happens right here in the U.S. She plays baseball.”

An article in a similar vein that same week, by Ed Nichols of The Daily Times in Salisbury, Maryland, was more explicit when Ramon Antonio de la Cruz, a university student in Havana, told Alvarez to make a choice: “Isabel puts it this way. ‘Number one is baseball; number two is Ramon.’”

Considering Alvarez’s command of English was limited, the story was probably told either through one of her Cuban teammates or through the imagination of the sportswriters.

Regardless, Alvarez attracted attention, whether she was playing for the Chicago Colleens, the Fort Wayne Daisies, the Battle Creek Belles or the Kalamazoo Lassies.

Nancy Blee and her family took in Lefty during the 1952 season.

Nancy Blee and her family took in Lefty during the 1952 season.

“It was the support of the Blee family and Lefty’s memory of her ‘sport self’ that carried her through that year,” Williams writes.

Alvarez’s career ended when she injured her knee during a 1954 game. She remained in Fort Wayne but Williams notes that the demise of the AAGPBL, the departure of her Cuban teammates, “the structure and built-in sense of family and community” made life difficult when she could no longer play the game.

However, Alvarez regained her sport-identity somewhat when she began playing in Fort Wayne softball leagues. Despite her personal battles, she had a satisfying career at General Electric before retiring in 1999.

During the 1980s, Alvarez began reconnecting with former members of the AAGPBL, who did not know her “until I opened my mouth.” “That crazy Cuban” had found her sport-identity once again.

Happy birthday to Isabel "Lefty" Álvarez! pic.twitter.com/6d3htbHP7n

— AAGPBL Official (@AAGPBL) October 31, 2019

Historians will enjoy the stories about women’s baseball and the turbulent times in Cuba under Batista, which eventually came under the thumb of another dictator, Fidel Castro.

Williams writes in a sentimental tone, but it works. One cannot help but root for the dark-haired, left-handed 15-year-old pitcher, who came to the United States with hardly any education and no command of the language.

“Lefty endured, and despite it all she was able to have a life that made her proud,” Williams writes.

From that perspective, Lefty Alvarez is truly in a league of her own.

Jenanne Lesko threw out a first pitch tonight on behalf of Isabel “Lefty” Alvarez & The Fort Wayne Daisies! ⚾️□ The Daisies were a part of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League from 1945 to 1954! □□ pic.twitter.com/uewYp6bJUK

— Fort Wayne TinCaps (@TinCaps) June 27, 2018

RSS Feed

RSS Feed