It’s the intangibles that made Ortiz great. The Boston slugger was the heart and soul of the Boston Red Sox team that finally broke the Curse of the Bambino with a World Series title in 2004, and he helped them win two more times before retiring after the 2016 season. He did it with leadership and swagger, humility and example, and he never forgot his humble roots.

Those intangibles, along with his slugging ability, will land him in the Hall of Fame when he becomes eligible in a few years.

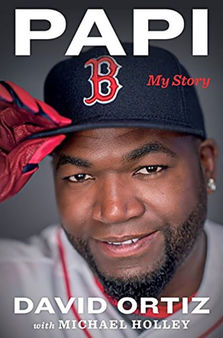

That’s why Papi: My Story (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $28; 262 pages) is such a satisfying read. The book is short, but Ortiz packs plenty of information and insight, with the help of Boston sportswriter/columnist/radio personality Michael Holley.

Just seeing Ortiz’s big bat in the middle of the Red Sox batting order was frightening enough. And sure, he could whine and become agitated if he believed a pitcher was throwing too close to him, or that he wasn’t getting enough respect. But here was a guy, brought up in the Dominican Republic by hard-working parents in a town “where there was a shooting every day” who could stand at a Fenway Park microphone and crudely tell terrorists who exploded bombs at the Boston Marathon that Boston was “our city” (you know the exact phrase, so I don’t need to insert the profanity.

But like the headline in the San Francisco Chronicle the day after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, what Ortiz said was powerfully appropriate in the context of the moment.

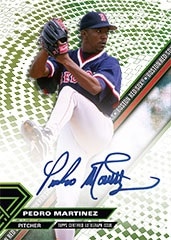

Ortiz gives the reader glimpses of the personalities of those Red Sox teams, extolling the work ethic of Manny Ramirez, the steely resolve of Pedro Martinez and the vision of general manager Theo Epstein. He also speaks of trust broken with former manager Terry Francona and the abysmal 2012 season piloted by Bobby Valentine. He writes of his run-ins with David Price when the left-hander was with the Rays, but adds that he now considers him a good friend. He’s a family man who had some rough patches in his marriage but worked them out.

nd from a personal standpoint, it’s hard to dislike a guy who named his first son D’Angelo.

He writes about the transition from the Minnesota Twins, where as a player he could enjoy anonymity, to Boston, where “there were no places to hide out.” He writes about the pain of losing the 2003 American League Championship Series to the New York Yankees, particularly when the Red Sox held a 5-2 lead in the eighth inning of Game 7. After Aaron Boone’s 11th-inning homer sent the Yankees to the World Series, Ortiz was “sick.”

“Too sick to be angry. Too sick to be analytical,” he wrote.

But 2004 would be a different story, as the Red Sox overcame a 3-0 series deficit in the ALCS to sweep the Yankees. Ortiz’s homer at Fenway Park gave the Sox a victory in Game 4, and his game-winning single in Game 5 made it a series again. The Red Sox would sweep the final two games at Yankee Stadium to win their first pennant since 1986, and would sweep the St. Louis Cardinals to win their first World Series title since 1918. The Curse was over.

Ortiz also reveals the origin of his nickname, “Big Papi.” He had a terrible memory for first names, and to compensate he would call everyone papi. Babe Ruth called everyone “kid,” so Ortiz in his own way carved out a nickname for himself.

He writes about being on “the list” of players who tested positive for a banned substance in 2003, and how he had to face rumors and innuendo when the list was revealed in 2009. “I was now a name in this war. It was endless,” Ortiz writes. “Say you didn’t do it enough and you sound guilty. Say nothing and your silence proves your guilt.”

While Ortiz said he bought legal supplements and vitamins over the counter, he denied that he ever bought or used steroids.

“And after I said it, I felt some of the tension leave my body,” he writes. “All I could share was the truth.”

The truth is that Ortiz carved out a unique place in Boston sports history, and his towering home runs and larger-than-life personality is presented well in Papi.

“I’m truly blessed to have had such a gratifying life in baseball,” he writes.

Baseball fans — who rooted for and against Ortiz — surely feel the same.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed