www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/consignment-of-the-week-muhammad-ali-10-page-speech/

|

Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a speech Muhammad Ali gave at a news conference shortly after his loss to Leon Spinks in February 1978:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/consignment-of-the-week-muhammad-ali-10-page-speech/

0 Comments

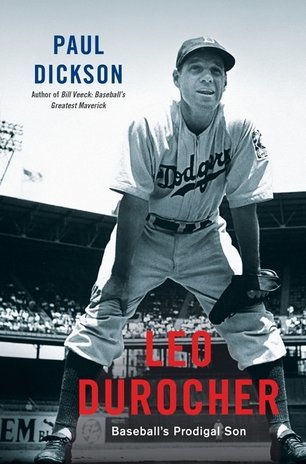

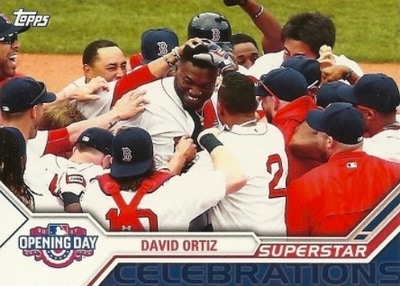

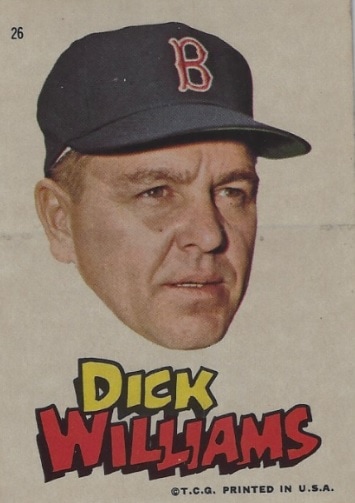

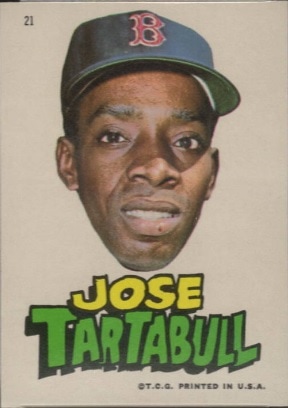

Opening Day is here, and it has a double meaning for baseball card collectors. While it’s true that major-league squads open their 2017 season this weekend, it also signifies the release of Topps’ Opening Day baseball. Opening Day is a spring tradition, with a design that mirrors Topps’ flagship Series 1 set (with an added Opening Day logo) and inserts that emphasize some of the fun fans can experience at the ballpark. The price is reasonable, too; expect a hobby box to cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $30 to $35. As always, Topps Opening Day is geared toward younger collectors, and the inserts certainly are evidence of that. A hobby box contains 36 packs, with seven cards to a pack. Some (not all) collectors will pull either a relic or autograph card from a hobby box. With a 200-card base set, it should be fairly simple for collectors to build an entire set. But to make things a little more difficult, Topps did throw in some card variations for certain players. Those photographs are more of a celebratory kind, or offbeat (in the case of Corey Kluber, the Indians’ ace is kicking a soccer ball), and fall every 256 packs. There also are parallels, with Rainbow Blue Foil, falling every seven packs. Some collectors might find 1/1 versions of Opening Day Edition and Printing Plates. True to the average, I pulled five Rainbow Blue Foils from the hobby box I sampled Mascots is a 25-card subset that pays tribute with some really corny phrases in some cases. Example: The Oakland Athletics mascot — the famous elephant that has been a franchise symbol for more than a century — “is happy to work for peanuts.” Other mascots include such standbys as the Phillie Phanatic, Billy the Marlin, Mr. Met, Fredbird and the Rally Monkey. Even Raymond, the Rays’ mascot, has a card. Cards will fall about one in every three packs, and I pulled 10 from the hobby box I opened. Incredible Eats is an 18-card insert set that showcases some of the unique food at different ballparks. Classic pastrami (Mets), South Philly Dog (Phillies), hot dogs and onions (Cubs) and bacon mac and cheese (Rangers) are some of the culinary treats. Topps does young collectors a service by not listing the prices for these delectable delights. I pulled eight of these inserts in the hobby box I opened. Opening Day at the Ballpark shows the inaugural games of the 2016 season at selected venues. There are 15 cards in the subset, and collectors can expect to pull seven of these cards from a hobby box. Superstar Celebrations contains 25 cards and will fall every three packs. These cards show the joy and fun of a team celebrating a big victory. The hobby box I opened also yielded a pair of inserts that are scarcer than the pack-an-insert offering in Topps Opening Day. Opening Day Stars falls one per hobby box; the card I pulled from the 44-card subset was of Kluber. The other card was a Stadium Signatures card of the Indians’ Francisco Lindor. This 25-card insert falls once every 420 packs, and don’t be misled by the reference to signatures. This insert merely shows players in the act of signing autographs. There is a parallel set with actual autographs too, but that occurs once in every 17,820 packs. Topps Opening Day is a fun companion to go along with the opening of the baseball season. It’s easy to collect, inexpensive, and just plain fun.  It is fitting that Paul Dickson’s new biography about Leo Durocher refers to the flamboyant player and manager in a way that would have made Branch Rickey smile. Leo Durocher: Baseball’s Prodigal Son (Bloomsbury Press; hardback; $28; 358 pages) is the perfect book title. Durocher had a history of doing great things, despite being controversial, tacky, self-centered, a bully, an umpire baiter and a win-at-all costs baseball player and manager. “I Come To Kill You,” is the title of the first chapter of his second autography, 1975’s Nice Guys Finish Last, and of a May 1963 article in the Saturday Evening Post, both co-written with longtime sportswriter Ed Linn. He quotes Rickey as saying that Durocher was a man who had “an infinite capacity for immediately making a bad thing worse.” But Rickey always defended his prodigal son, and in this well-researched, page-turning book, Dickson shows the reader why. Dickson’s work is based on few personal interviews, but is chock full of what he does best — research — and he digs for information and puts it together in a smooth narrative. Dickson combed newspaper archives and the personal papers of Rickey, Jackie Robinson and journalist Arthur Mann to supplement his research. In fact, Dickson calls the writing and collected letters of Mann to be the one source that was the most crucial in “getting to Durocher.” No fewer than 24 magazines and major newspapers were tapped as source material, which helps provide a more balanced look at the Lip. Dickson is a prolific writer of baseball history. His 2012 work, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick, was a detailed and precise book that shed new light on baseball’s ultimate showman. Dickson also has written The Unwritten Rules of Baseball, The Hidden Language of Baseball, The Baseball Dictionary and Baseball’s Greatest Quotations. In The Lip, his 1993 biography of Durocher, longtime sportswriter Gerald Eskenazi called him a “Beau Brummel of the gray flannel set” who was just as comfortable socializing with actors, actresses and members of the mob as he was directing a baseball game. Eskenazi also made a strong case for Durocher being enshrined into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and he was finally elected by the Veterans Committee in 1994, three years after his death. Dickson agrees, writing that Durocher performed on the main stages of New York, Chicago and Hollywood. “He entered from the wings, strode to where the lights were the brightest, and then took a poke at anyone who tried to upstage him,” Dickson writes. Dickson examines Durocher’s gambling, which had been “a constant” in his life. It did not affect the Dodgers in 1941, as Brooklyn won its first National League pennant since 1920. One interesting angle Dickson takes concerns a possible reason why Durocher was suspended for the 1947 season. Commissioner Happy Chandler essentially put a gag order on all involved parties, so no real concrete reason was ever given. Venerable baseball author Roger Kahn said he confronted Durocher in 1990 about an accusation that his suspension was because he had fixed the 1946 National League playoffs against the St. Louis Cardinals. Durocher hotly denied it, calling it “outrageous,” with some expletives thrown in for good effect. “You writers either say I tried to win too hard or that I didn’t try to win at all,” Durocher told Kahn. Dickson does some more digging and concludes that the charge was baseless. And honestly, the only reason the rumor even had legs was because it sounded like something Durocher might have done. Durocher confessed in his autobiography that he always spent beyond his means and needed advances from owners like Cincinnati’s Sidney Weil to stay afloat during his career, so being a prime target for gamblers is not a ridiculous theory. Dickson writes that the Dodgers’ clubhouse under Durocher was “overrun” with gamblers, bookies, ticket scalpers and racing handicappers. That ended when Rickey became general manager after the 1942 season. Dickson trots out some of the familiar stories — Durocher’s bench jockeying as a player was legendary, and the number he played on Bob “Fats” Fothergill is worth repeating. In this second game of a doubleheader in Detroit on Sept. 27, 1928, Fothergill already had gone 2-for-3 with a triple and two RBI when he came to bat in the seventh inning. New York led 8-5 but Detroit had two runners on base and darkness was falling. Durocher called time, ran toward the plate from his position at second base and told the umpire that “there was a man batting out of place.” Told by the umpire that the lineup was proper and Fothergill was indeed the hitter, Durocher said “Fothergill? Ohhhh, that’s different. From where I was standing, it looked like there were two men up there.” That did it. Fothergill, furious, took three straight strikes to end the game, and, Dickson writes, “from that point on, baseball was more than a game for Durocher — it was theater.” Elevated to a starting role in St. Louis, Durocher became team captain and helped the Cardinals win the World Series in 1934. As a player, Durocher was mediocre — Babe Ruth called him “The All-American Out” — but he really excelled as a manager. He won 2,008 of the 3,739 games he managed over 24 seasons and won National League pennants with the Brooklyn Dodgers (1941) and the New York Giants (1951, 1954). He also managed the Chicago Cubs for 6½ seasons and the Houston Astros for slightly more than a season. He had a winning record at every stop, but wore out his welcome at every venue. Durocher was a manager who deserved credit for backing Jackie Robinson as he broke into the majors in 1947 (although Durocher did not manage him during the regular season because he was suspended by Commissioner Happy Chandler), and for nurturing a young Willie Mays into superstardom with the Giants. Just as he was as a player, Durocher was equally cantankerous as a manager. When pressed by writers, Dickson writes, Durocher admitted that his fiercest arguments with umpires came “when he believed the call had actually had been right but close.” Durocher figured that the umpires, with Durocher’s arguments still ringing in their ears, would call the next close play in the Lip’s favor. Durocher’s shining moment as a manager came during spring training in 1947, when he squashed a potential boycott by players who did not want Robinson on the Dodgers’ squad. The low point came in the summer of 1969, when he went AWOL for a day during the heat of a pennant race to visit his stepson at Camp Ojibwa in Eagle River, Wisconsin. Dickson dissects Durocher’s second autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Last, and notes how the former Cubs manager ripped stars Ron Santo and Ernie Banks. The attack on “Mr. Cub” elicited the most response, as Durocher called Banks a phony. Dickson is a gentleman, and while he does not openly rip the second autobiography, he shows enough discrepancies and self-embellishment by Durocher to let the reader decide. In Leo Durocher: Baseball’s Prodigal Son, Dickson takes a balanced, impartial look at a man whose baseball career spanned a half century. Always colorful and controversial, Durocher deserved a fresh look. Dickson provides it with strong research and an excellent narrative. Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1967 Topps Red Sox sticker set, a 33-sticker set that was a regional test issue 50 years ago:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1967-topps-red-sox-stickers-recall-impossible-dream-season/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the summer release of Upper Deck's Goodwin Champions set:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-goodwin-champions-offer-eclectic-mix-new-wrinkles/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the upcoming release of Upper Deck's Fleer Showcase hockey set.

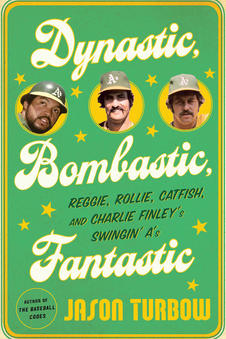

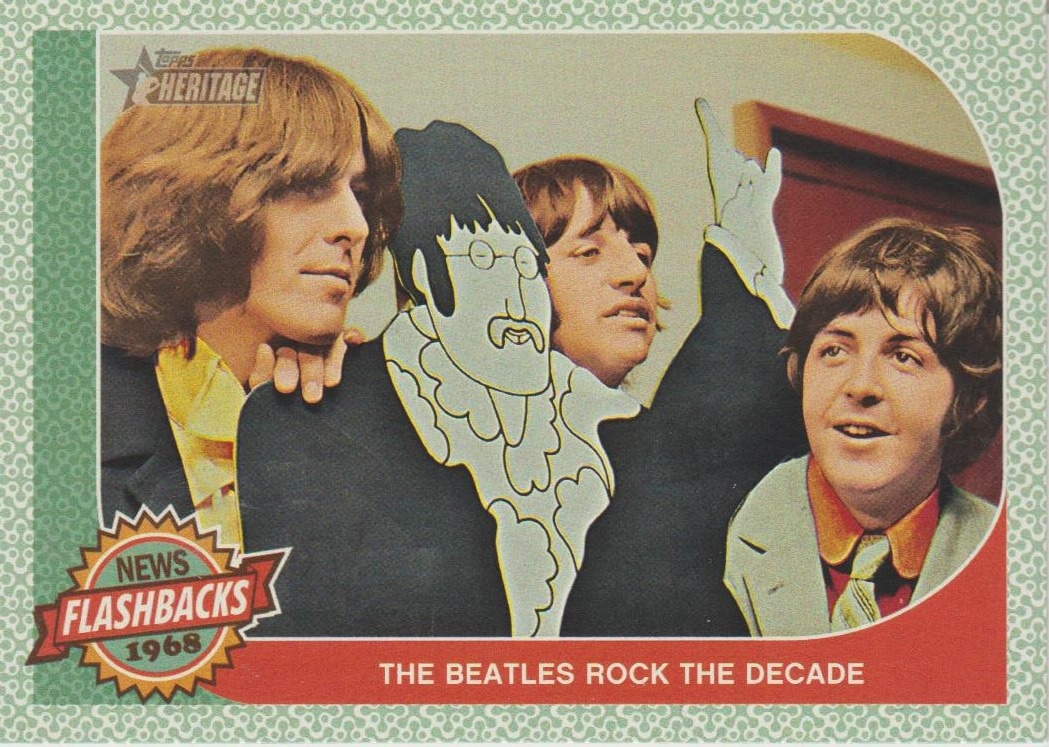

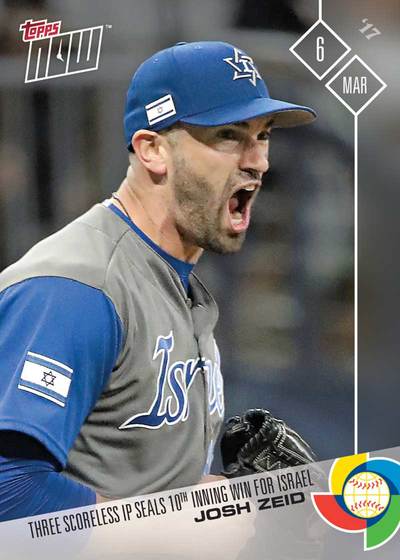

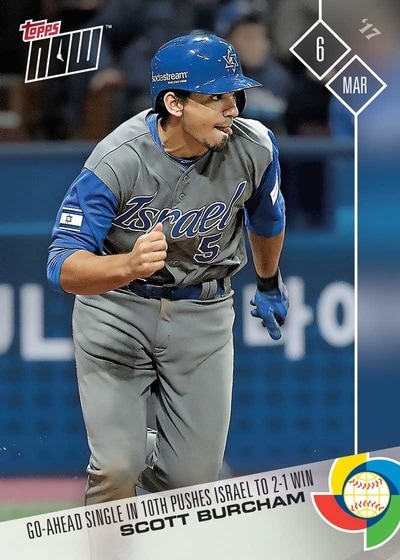

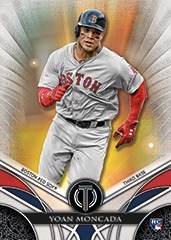

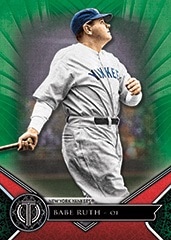

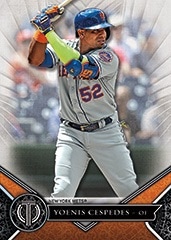

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2016-17-fleer-showcase-hockey-preview-checklist-boxes/  Burlap never looked so beautiful. The 2017 Heritage baseball set continues Topps’ tribute to its vintage set, and the 1968 design is the focus. The 1968 set is a nostalgic one for me, as I was 10 years old going on 11 and neck-deep into the card collecting experience. Packs of Topps cards were still five cents apiece, and while nickels were hard to come by, every spare bit of change was used to buy cards. The design was simple, with players posing in stilted batting and pitching poses or in glorified mug shots. The vertical design was perfect, and the only horizontal cards one saw were the “special” cards — All-Stars (the backs created a picture when stacked side by side), rookies, World Series highlights (I still love the effect that makes it look like you are watching the action on television) and league leader cards.  The player’s photo was framed by that burlap-looking texture, with a circle in the bottom right-hand of the card that listed the player’s position in thin black type and his team name in larger white or yellow block letters. The player’s name appears at the bottom, with his first name in small black letters and his last name beneath in larger red letters. The card backs also were vertical, with a cartoon giving a trivia question at the bottom, stats in the middle and the player’s name at the top in large black block letters set against a white, oval backdrop. What Topps could write about the player actually depended on the player’s longevity; those who had long careers and many lines of statistics had a shorter narrative, while younger players with shorter stat lists were given longer paragraphs to fill out the back.  The 2017 Topps Heritage set mirrors that classic look. There are 500 cards in this set, with the final 100 cards serving as the usual difficult short prints. A hobby box contains 24 packs, with nine cards to a pack. Topps promises an autograph or relic card in every hobby box, in addition to a box topper that could include anything from 3-D cards, an advertising panel, posters, poster autographs or original 1968 cards stamped in gold foil. Price for a hobby box should fall in the $80 to $100 range, depending on the retailer.  In the hobby box I opened, I received an original 1968 card that was stamped. The player was Washington Senators pitcher Dick Bosman. Buybacks continue to be plentiful in 2017, as Topps continues its Rediscover Topps promotion, where original cards are stamped on the right-hand side with, you guessed it, “Rediscover Topps” in bronze (the most common foil stamping), silver, gold, blue and red. I pulled five of these cards (three bronze, two silver) from the hobby box I sampled. What made the Topps cards of the 1960s so distinctive was that the card backs listing the player’s statistics also included their minor-league years. That is not the case with the 2017 Heritage set, and that’s a little disappointing. It might have been fun to see what route today’s players took to reach the major leagues. It's also gratifying that Topps stayed true to the original color coding of the teams on the card front circle. In 2017, just as in 1968, teams like the Cardinals and Tigers are in yellow, the Giants are in green, and the Yankees are in red. The Reds, for some reason, remain a puzzling blue. The 1968 season was the final season before the addition of the Padres, Expos, Royals and Seattle Pilots (now Brewers), so Topps picked some random colors. Same goes for the Mariners, Blue Jays, Rays, Diamondbacks, Marlins and Rockies.  In addition to the 500-card base set, Topps throws in its usually maddening and challenging variations. Several players have more than one variation, so keep a sharp eye out. The differences could be a color swap on the circle in the lower-right hand part of the card front, or action images, throwback uniforms, traded cards, rookie cards, or simply just errors. A throwback card of Bryce Harper, for example, shows the Nationals star wearing the uniform of the old Negro League Homestead Grays, while Danny Duffy sports the uniform of the Kansas City Monarchs, instead of the Royals. An error card of Ichiro lists him as a pitcher, while Corey Seager’s birth date is incorrectly listed as April 4, 1989 (he was born April 27). The American League pitching leaders card has Rick Porcello’s name properly spelled on the front, but “bungles it” by spelling it as “Porsello” on the back. “Traded” card variations, include when a player was acquired, and from what team. The rookie variation card takes one of the two players listed on the base card and turns him into a solo card; Aaron Judge, Yoan Moncada and Alex Reyes are examples. Some of the players also are shown in action poses, rather than the staid 1960s-style poses. The color swap cards show the team/position circle in black. If you feel like you might go blind looking for the differences, don’t despair. The code numbers at the bottom of the card backs will give you a clue. It’s usually the last few digits, and base cards end in 1867. The others are the high-numbered base short prints (69), error cards (70), rookie cards that are solo shots, and action cards instead of the posed shots (71), throwbacks (72), traded (73) and color swap (74).  The hobby box I opened yielded 203 base singles, with nine high numbers and one variation—a Manny Machado action shot. There are parallels for the base set, too. Blue bordered cards are numbered to 50 and are hobby exclusives. Bright yellow backs are numbered to 25 and gray backs are limited to 10, while the flip stock cards are numbered to five. As usual, chrome parallels are also thrown into the mix. The inserts in the 2017 are familiar ones for collectors. New Age Performers is a 25-card set that falls two per hobby box; I pulled Carlos Correa and Orlando Arcia. Baseball Flashbacks is a 15-card set that highlights the various achievements and progress of certain players; the card I pulled was of Joe Morgan, who was starring for the Houston Astros in 1968. News Flashbacks is another 15-card set that features some of the key events of 1968, which was one of our country’s most turbulent years. I pulled two of these cards — the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, which dramatically altered the course of that war; and the Beatles, who released the double-record “White Album” in ’68. Other cards recall the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Mexico City Olympics, Apollo 8’s orbit of the moon, and the debuts of “60 Minutes” and the Special Olympics.  Then and Now is another 15-card set that couples a star from 1968 with a current player. They fall one per 20 packs, and surprisingly, I did not pull one from the hobby box I opened. A new insert addition, which also was unique to the 1968 set, is the Topps 1968 Game card set. This is a 30-card offering that features a player and a baseball action, like a home run, double play, strikeout, etc. I pulled two of these cards, which feature a blue back. They had a New York flavor — Yoenis Cespedes of the Mets, and Gary Sanchez of the Yankees. There is also a retail version at Target, a 15-card rookie set that features red backs. The hit I received in the hobby box I opened was a Clubhouse Collection, game-used uniform swatch of Tigers’ star Miguel Cabrera. The 2017 Topps Heritage set continues the nostalgia of the 1960s, and the product is marching slowly toward the 1970s. But 1968 was a special year. I also pulled off quite a trade. A friend of mine needed one card to complete his set — Andy Kosco, of all people. It was card No. 524 in the 596-card set, and I had at least two of them, possibly three. And he worked on me for weeks for the card and I held out until he put together a package that included Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Horace Clarke (hey, I needed him …), Brooks Robinson and Ernie Banks. I’ll never forget that trade. I did pretty well, I think.  Managers and coaches preach harmony and team chemistry. Never upset that delicate balance; distractions can tear a team apart; if you have a complaint, keep it in-house and sort out among each other. The Oakland A’s of the early 1970s blew that theory out of the water. They were the last team to win three consecutive World Series — from 1972 to 1974 — and the first since the dynastic New York Yankees did it from 1949 to 1953. En route to five straight American League West titles from 1971 to 1975, the A’s scrapped, clawed and fought with a white-hot intensity — and that was in the locker room, on airplanes and in hotels. They were just as abrasive on the field, too, and their one common bond was contempt for their penny-pinching owner. In Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish and Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $26; 386 pages), author Jason Turbow presents an absorbing, detailed and entertaining look at the dynasty that Major League Baseball probably wanted to sweep under the rug. Turbow, who wrote “The Baseball Codes: Beanballs, Sign Stealing, and Bench-Clearing Brawls: The Unwritten Rules of America's Pastime” in 2010, had plenty of material to work with as he researched the Oakland A's. Team harmony? In October 1972, the A’s had just clinched their first World Series berth since 1931, and pitchers John “Blue Moon” Odom and Vida Blue nearly came to blows when Odom took umbrage at Blue’s insinuation that his fellow pitcher had “choked” in the series-clinching victory by not going the distance. Odom had his share of instigation, too. On the eve of the 1974 World Series, Odom taunted reliever Rollie Fingers about his marital difficulties. “Moon,” Fingers said, “you can’t even spell ‘divorce.’” “Yeah,” Odom retorted, “but your wife can.” These guys weren’t called the Swingin’ A’s for nothing. Another time, Reggie Jackson and Billy North got into a knock-down, drag-out fight in the middle of the clubhouse, where some the A’s were playing a game of bridge. As Jackson and North rolled around the clubhouse, the game went on. “I had a slam bid I wanted to play, and damned if people were fighting. I still played it,” Dick Green told Turbow. Sal Bando put it all in perspective after tempers cooled. “Well, that’s it. We’re definitely going to win big tonight.” Bando was a prophet as the A’s won 9-1, Turbow writes. Turbow structured the book in three parts: Ascendance, covering the period from 1961 to 1971; Pinnacle, the World Series championship years of 1972 through ’74; and Descent, chronicling the team’s decline from 1975 to 1980. Turbow interviewed players, coaches, broadcasters, sportswriters and front-office workers. He visited the homes of Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace and North, visited Mike Epstein’s baseball camp, and interviewed Green in the cafeteria at the Mount Rushmore historic site. The only key members he did not interview were Jim “Catfish” Hunter, manager Dick Williams and owner Charlie O. Finley, who had died by the time Turbow began his research. Alvin Dark, who succeeded Williams as manager, died in 2014. In a book full of mavericks and antiheroes, Finley was the biggest of them all. So big, that Turbow mostly refers to him as “the Owner” in most of his narrative. Finley was a rags-to-riches story, a businessman who struck it rich in the insurance business. After several failed attempts to buy major-league teams, Finley bought the Athletics in 1961. He spruced up the ballpark in Kansas City, where the Athletics had moved from Philadelphia after the 1954 season. A one-man scouting team and his own general manager, Finley scoured the country for baseball talent. By the late 1960s that talent was beginning to gel with players like Hunter, Fingers, Jackson and Bando, and Finley moved the A’s west to Oakland for the 1968 season. Turbow notes that Finley’s legacy was one of “pure duality.” He was a baseball visionary, “a perpetual mover or whom rest was never an option.” But he also was a narcissist and a self-promoter; Finley not only ran the show, he wanted to be the show. He cut a figure, Turbow writes “somewhere between tyrant and punch line.” Finley rarely got good press, Turbow writes, because he rarely deserved it. And the owner (as opposed to Owner) was cheap. There were no programs for Game 1 of the 1973 World Series in Oakland because Finley was slow to pay the printing costs. He sold tickets in the center field bleachers at the Oakland Coliseum, hindering the hitters’ sight lines — but 5,000 tickets went unsold in the upper deck. Turbow quotes Rudi saying that Finley did not hire enough people to answer ticket requests. “There were thousands of checks sitting there for people wanting tickets for the World Series, which were not filled,” Rudi said. “Finley was just too cheap.” After passing out beautiful World Series rings to the players in 1972, Finley went cheap in ’73, as the new rings did not feature a diamond but instead had green glass, Turbow writes. Finley’s clumsy attempt to “fire” Mike Andrews after the second baseman made some costly errors in Game 2 of the 1973 World Series nearly resulted in a boycott by the A’s. It certainly convinced Williams to resign after Oakland won its second straight Series crown. It was a microcosm, Turbow writes, of the turbulent A’s. “Angry players who felt abused, and a manager who could take no more,” he writes. “Finley acts, players react, nothing changes.” Alvin Dark, a recycled former manager for Finley (he managed in Kansas City in 1966 and 121 games in 1967), took over in 1974. The players were slow to respect him and believed he was a Finley puppet. “I knew Alvin Dark was a religious man,” Blue said. “But he’s worshiping the wrong God — Charlie O. Finley.” The anecdotes Turbow spins in this book are alternately hilarious, sad, and shake-your-head amazing. “You have all heard of John the Baptist,” a visibly inebriated Finley told an audience of fans gathered at a restaurant in 1974. “John the Baptist was a winner. Well, tonight we’ve got Alvin the Baptist. Alvin the Baptist is a loser.” Hugs all around. And yet, the A’s continued to win. When Finley berated Dark loudly over his lack of usage of pinch-runner Herb Washington, the players began to feel sorry for their manager. After half a decade of success the A’s were broken up, victims of free agency and Finley’s refusal to keep his star players. Turbow’s prose is lively and entertaining, and some of the footnotes he writes are mini-chapters in their own right. Don’t skip them; some will make you laugh out loud, while others will offer a solid explanation of a particular episode. The Swinging A’s could not exist in today’s major-league world. They were too scruffy, too loud, too opinionated and too confrontational. But they also were winners — in spite of their turmoil, and in spite of their mercurial owner. In Dynamic, Bombastic and Fantastic, Turbow weaves a tale that bubbles and percolates on every page. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the online Topps Now cards being offered during the World Baseball Classic:

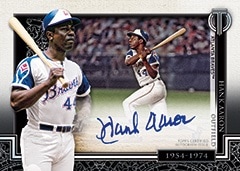

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-now-world-baseball-classic/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2017 Topps Tribute set, which will be released March 29:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/72533-2/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1963 Bazooka All-Time Greats set:

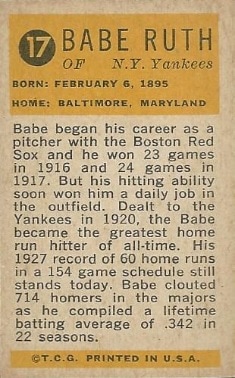

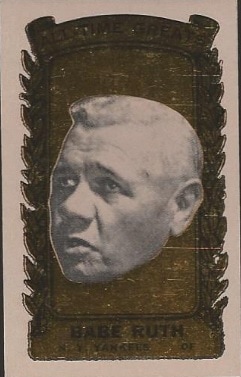

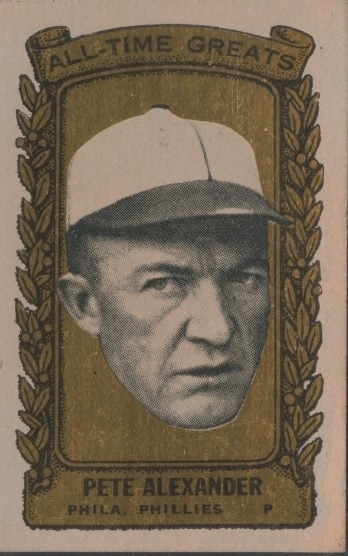

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1963-bazooka-all-time-greats-an-affordable-vintage-set/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed