www.challengetheyankees.com/

|

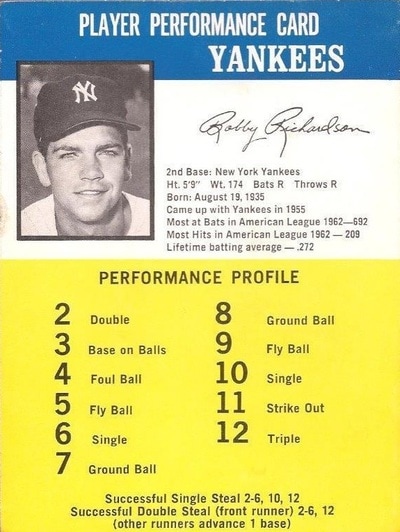

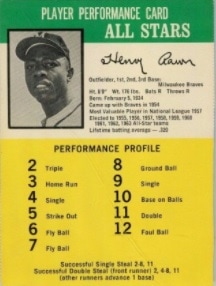

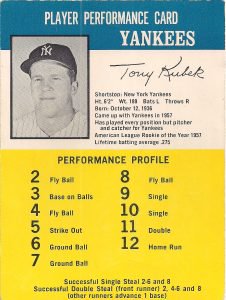

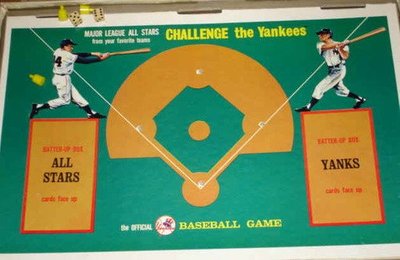

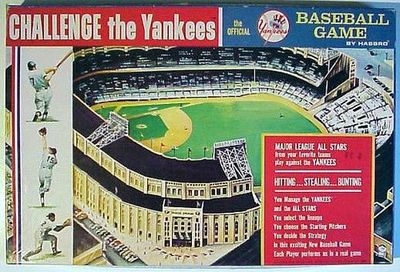

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Roger and Rich Franklin, who are reviving the 1960s baseball board game, Challenge the Yankees. Roger Franklin invented the game more than half a century ago. www.challengetheyankees.com/

0 Comments

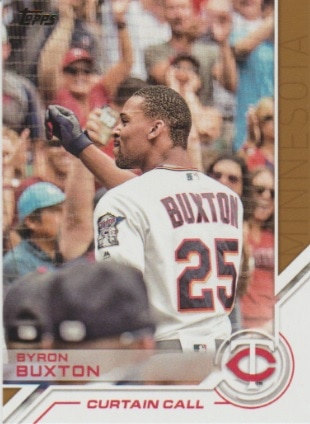

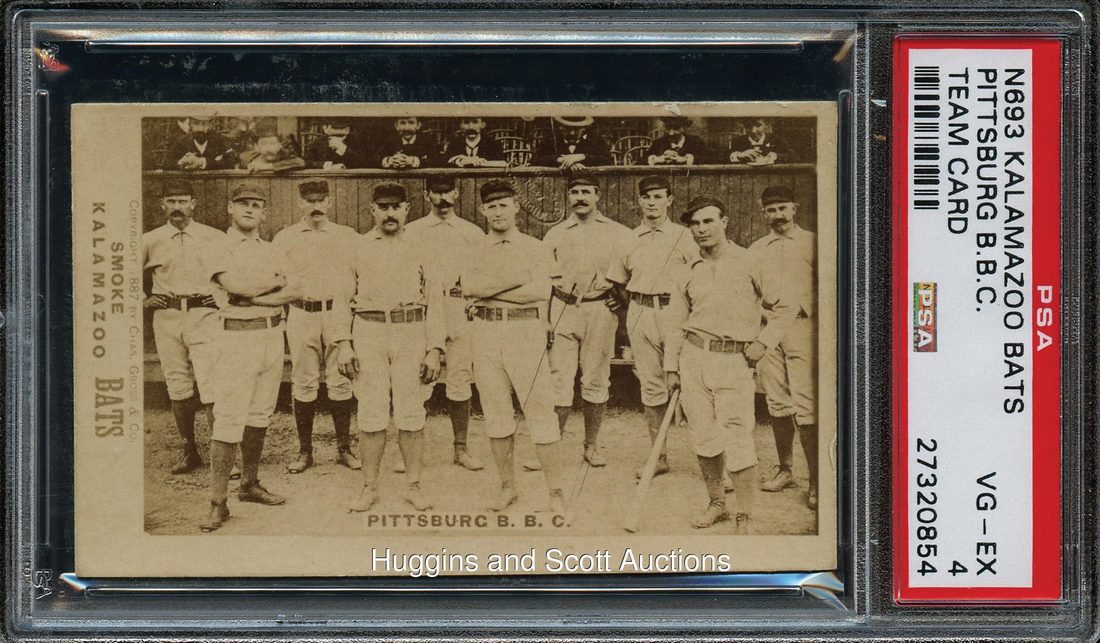

As one might expect, Topps Series Two follows the same pattern of the first series released earlier this year. A hobby box will contain 36 packs, with 10 cards to a pack. Topps is promising one autograph or relic in every hobby box. The collation is good, as there was no duplication. I pulled 309 of the 350 cards in the base set. The design remains the same as Series One. The one criticism I have (and it might be a quirk in the box I opened) is that there were several horizontally designed cards that were miscut. There was a white gap at the top, and on the back there was a white line there, too. While that was common during the 1960s and ’70s, a collector hardly sees miscuts any more. Odd. There are parallels in the set, and I pulled four rainbows from the hobby box I sampled. I also pulled a hobby box exclusive black parallel of Andrew Toles, numbered to 66. Gold parallels are numbered to 2017; other parallels include Vintage Stock (numbered to 99), Mother’s Day Hot Pink (50), Father’s Day Powder Blue (50), Memorial Day (25), hobby exclusive Clear (10) and Negative, and 1/1 Platinum and Printing Plates. The big hit in the box was a Major League Material relic card of San Diego’s Wil Myers. The card is created in thick card stock and contains a small uniform swatch.  The inserts in Series Two combine some familiar sets with a few new ones. First Pitch returns for another run, honoring celebrities who go to the mound and deliver the ceremonial pitch before a game. There are 20 cards in the subset and I pulled five of them from the hobby box I opened. MLB Network inserts also return for Series Two. There are 10 cards in the subset, and the card I pulled was of Brian Kenny. Topps Salute is a 100-card subset that returns with players grouped into four categories: Curtain Call, Legends, Spring Training and Throwback Jerseys. I pulled nine of these cards, plus a red parallel of Cleveland’s Tyler Naquin, numbered to 25. Baseball Rookies & All-Stars is another 100-card subset and features players in the wood-grain design of the 1987 Topps set. I pulled nine from the hobby box I opened.  Two new parallels debut in Series Two. Major League Milestones consists of 20 cards and sports a horizontal design. The cards pay tribute to players who put up milestone numbers, like Miguel Cabrera’s 1,500th RBI or Mark Teixeira’s 400th home run. I pulled four of these cards. And Memorable Moments is a 50-card subset that recalls some of baseball’s iconic games, personalities and achievements. I pulled nine from the hobby box I opened. Finally, buybacks return with “Rediscover Topps” cards sprinkled throughout the hobby box. I pulled six of these cards, which are stamped in various colors in foil to signify their rarity. Bronze is the most common stamp, followed by silver, gold, blue and red. As in previous years, Topps simply follows the formula that is used in Series One, introducing players who didn't make it in the first run and throwing in a few new insert sets. It's an effective strategy, and for the traditionalists who wait for Topps' flagship set every year, that consistency is a comforting thing. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a flea market find in Massachusetts -- an 1887 Kalamazoo Bats card of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys:

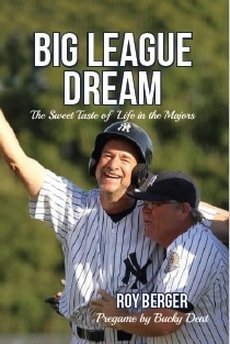

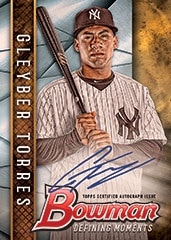

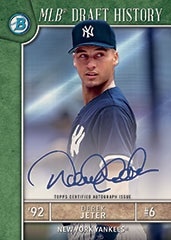

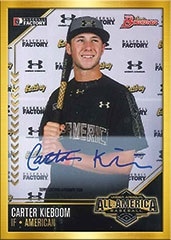

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/huggins-scott-auctioning-off-rare-team-card-from-1887/  Major-league baseball players like Gary Bell “rubbed shoulders with the greats of the game,” Roy Berger writes in his latest book. “I had their trading cards.” It’s a great, self-deprecating line from Berger’s second book, Big League Dream: The Sweet Taste of Life in the Majors (Mountain Arbor Press; paperback; $16.99; 262 pages). Berger is president/CEO of MedjetAssist, a global air medical transport. But at least once a year, he puts on a uniform and competes in baseball fantasy camps for a week. Berger recounts the friendships he made with former major-leaguers during the camps in an engaging, entertaining style. Reading Berger is like sitting in a sports bar swapping stories with a friend, except the friend has the better tales to tell. Berger, now 65, attended his first fantasy camp in 2010 and met his baseball idol, Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski. What began as the realization of a dream became an obsession, as Berger was hooked. He’s right: There is something alluring about trying to recapture your youth, particularly if you love baseball. That was captured in Berger’s first book, 2014’s The Most Wonderful Week of the Year. Big League Dream takes a baseball fan back in time, as Berger is an eager and willing listener as former baseball players. tell their stories. Many are not big stars, but they are interesting nonetheless. In addition to Bell, Berger devotes chapters to Jake Gibbs, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, Fritz Peterson, Maury Wills, Ron Swoboda, Mike LaValliere, Steve Lyons, Kent Tekulve and others. There’s Bucky Dent, who wrote the foreword (in a whimsical touch, Berger calls it the “Pregame”); Jon Warden, who went 4-1 for Detroit in the Tigers’ World Series championship season of 1968; Chris Chambliss, remembered for his walk-off homer in the 1976 ALCS; and Kansas City teammates John Mayberry and Dennis Leonard. Hockey announcer Mike “Doc” Emrick also is profiled, and Berger devotes a chapter to women who have competed in fantasy baseball camps. Finally, Berger expresses the joy of having his two sons attend the same camp he was participating in. There’s a funny line from Chambliss, too. Berger was on third and the bases were loaded, and as a third base coach, Chambliss was giving the usual instructions to the runner. And then ... “I’m not sure if you realize it or not, but the bases are loaded with Bergers,” Chambliss said, noting that Berger’s sons were the other runners on the bases. Berger has a knack for telling a good story, and he gives the reader a nice behind-the-scenes look. The only criticism is some of the players' names are misspelled, like Dal Maxvill (spelled as Maxville), Tom Lasorda (spelled as LaSorda), Denny McLain (spelled as McClain), Carl Sawatski (spelled as Swatski), and even Caitlyn Jenner (spelled as Caitlin; no, Jenner was not in a camp, but Berger was trying to make a pop culture reference). Berger said that the mistakes have been caught and will be fixed for the second printing of the book. The mistakes do not detract from the overall theme and feel of the book. The cover shows Berger at the pinnacle of his camp experience — getting a bear hug from Dent after driving home the winning run in a 2014 fantasy game at Tampa’s Steinbrenner complex. Berger estimated that he had spent approximately $35,000 — his costs since beginning to play in fantasy camps — before realizing the thrill of a walk-off hit at age 62. It may not have had the drama Berger’s idol, Mazeroski, generated when he ended the 1960 World Series with a walk-off homer. But on that day in Tampa, Florida, a fantasy camper realized his ultimate dream. “Sometimes they might come at a price, but dreams, even old, dated, forgotten-about, and parched ones, can come true,” Berger writes. “I had my ‘Big League Dream.’ Best money I ever spent.” Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2017 Bowman Draft baseball set, which comes out Dec. 6:

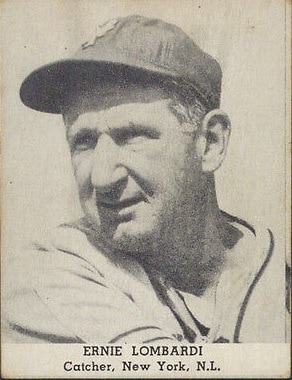

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-bowman-draft-baseball-preview-checklist/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1947 Tip Top Bread card set:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1947-tip-top-bread-baseball-cards/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an action photo involving Joe DiMaggio and Lou Gehrig during the 1938 All-Star Game:

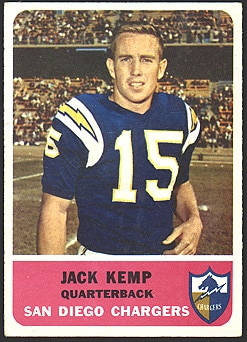

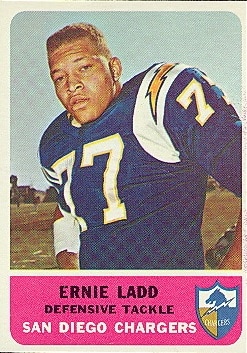

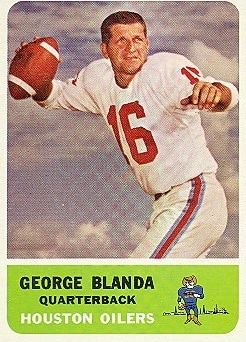

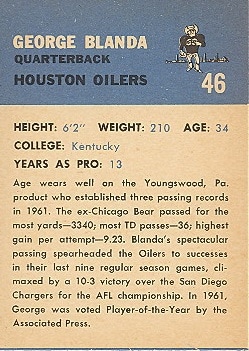

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/photo-of-the-day-slide-clipper-slide/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1962 Fleer football set, which was exclusively made up of American Football League players.

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1962-fleer-football-was-slim-but-trim/

Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a Home Run Derby promotion offered by Topps in conjunction with today's debut of 2017 Topps Series 2 baseball:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/topps-offering-hr-derby-ticket-promotion/

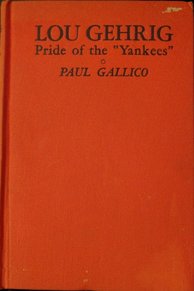

The first baseball book I ever read as a child was Paul Gallico’s 1942 book, Lou Gehrig: Pride of the ‘Yankees.’ I still have it, too. As a fourth-grader in Brooklyn, I bought my first left-handed baseball glove from a classmate for $5. It was a first-baseman’s mitt, a Gehrig model by Rawlings with his signature on the inside of the glove. Wish I still had it.

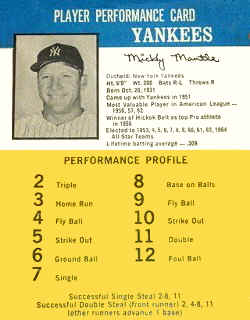

Mickey Mantle was my contemporary baseball hero during the 1960s, but Gehrig was the player — and man — I wanted to be: honest, hard-working, muscular and humble. He was the epitome of the New York Yankees. “He entered the hearts of the American people, because of his living as well as his passing, he became and was to the end, a great and splendid human being,” Gallico wrote. The 1942 movie, Pride of the Yankees, was similarly sentimental, starring Gary Cooper in the title role as Gehrig in the first real biography movie about an athlete. It immortalized Gehrig’s famous and emotionally charged “Luckiest Man” speech he gave on July 4, 1939, at Yankee Stadium, and also showed the love story between the slugger and his wife, Eleanor.

For all of its schmaltz and sticky sweet sentimentality, the film remains an American classic. Now, readers can get an inside look about how the film came together in the months after Gehrig’s death from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) — which would be more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease — on June 2, 1941.

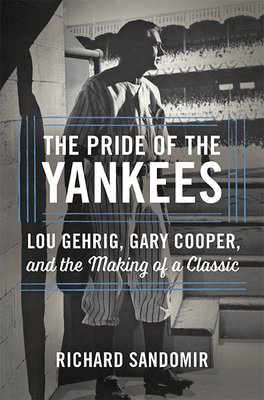

The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic (Hachette Books; hardcover; $27; 293 pages) by Richard Sandomir is interesting, insightful and revealing. Sandomir, an obituary writer for the New York Times, wrote about sports media and business for 25 years. In this book, Sandomir analyzes the reluctance of a studio mogul (Samuel Goldwyn), the persistence of Gehrig’s widow, the search to cast the right people, and the impact the movie still has today. One of the movie’s goals, Sandomir writes, was to “idealize baseball” through its “worshipful treatment” of Gehrig. The goal was achieved, but there were some hurdles. The movie was “produced by a man, Goldwyn, who knew nothing about baseball, starring a man, Cooper, who had never played baseball, and shot by a cinematographer, Rudolph Mate, who was also new to baseball,” Sandomir writes. Still, this combination would portray baseball as “a bright and shining sport.” Cooper, who won an Academy Award in 1942 for his lead role in Sergeant York, was not built like Gehrig, did not sound like him, and definitely did not have the Iron Horse’s baseball skills. Teresa Wright, who would play Gehrig’s wife in the film, was the perfect, lively counterpoint to the taciturn Cooper — just as Eleanor Gehrig would be to Lou Gehrig. Both actors would be nominated for Academy Awards for their roles in Pride, although neither would win. Gallico wrote the original screenplay and kept a running correspondence with Eleanor Gehrig through letters, which Sandomir relates in great detail. These letters really bring the story of the film to life and are a key reason why Sandomir’s book is such a compelling read. Gallico’s opinion of Gehrig can be summed up in the first chapter of his own book, where he said he called it “Lou Gehrig — An American Hero,” because “he was a hero and was totally our own.” Sandomir is less sentimental as he cuts through the hero worship and presents the business of Hollywood with smooth, effective prose.

Sandomir also points out the film’s many inaccuracies. Hollywood has a way of taking poetic license with a story, shaping it to meet its own standards for creating a box office success. For example, Goldwyn had Gehrig meeting his future wife, Eleanor Twitchell, seven years before they actually did. Gehrig worked for the city of New York after he retired, but after he gave his famous speech at Yankee Stadium. The movie depicts him working in the parole commission office before the speech. Gehrig and his wife were married in their future apartment, several days before a formal wedding was to take place. In real life, Gehrig was concerned that his overbearing mother would try to interfere or make a scene in a Long Island setting so arranged what amounted to an elopement. In the movie, Goldwyn ridiculously places Mom and Pop Gehrig looking on benevolently as Lou and Eleanor recite their vows. There was plenty of real-life tension between Eleanor and Christina Gehrig, but as Sandomir writes, that angle was softened somewhat. As Sandomir notes, “Eleanor’s harshest comments to Gallico about Mom (Gehrig) never found their way near the film.” The romantic tone that Goldwyn wanted to set would never allow for Eleanor’s “characterizations of Gehrig family dysfunction.” The day Gehrig ended his consecutive game streak of 2,130 games also was misrepresented. Gehrig actually took himself out of the starting lineup before the May 2, 1939, game at Detroit. But telling manager Joe McCarthy hours before the game was “not dramatic,” so the film deviates, with Gehrig informing his manager to replace him after the sixth inning with Babe Dahlgren. “It works dramatically,” Sandomir writes, “but squelches what really happened that day.” Among the interesting nuggets that Sandomir sprinkles throughout the book is how Dahlgren negotiated himself out of the film because of his high salary demands. One actor who did play himself was Babe Ruth, much to the consternation of Gehrig’s wife. Ruth lost nearly 50 pounds to appear in the film, but Eleanor Gehrig believed with “some rancor” that the Bambino, who overshadowed Lou Gehrig through much of his career, would try to be a scene-stealer in Pride. But Ruth’s name would lure paying customers. “It was impossible and impractical to keep Ruth out,” Sandomir writes. Still, Eleanor Gehrig knew that Lou had suspicions that Ruth had once slept with her — a sticking point that ended the friendship between the two sluggers. Eleanor’s emotions about the Babe were “tough and raw,” but Goldwyn prevailed. “She did not get her way, and the Pride is better for it,” Sandomir writes.  My copy of Paul Gallico's 1942 book, "Lou Gehrig: Pride of the 'Yankees'" My copy of Paul Gallico's 1942 book, "Lou Gehrig: Pride of the 'Yankees'"

Sandomir also addresses the myth of baseball scenes in Pride being filmed with the negatives reversed in some scenes, a fascinating offshoot of the film. Former baseball star Former major-leaguer Lefty O’Doul worked with Cooper, explaining that he should swing the bat like he was chopping wood — a chore the actor was familiar with. Another Babe — Babe Herman — appeared in the long shots of Gehrig in the film, since his baseball ability was much more credible than Cooper’s.

The most memorable scene in Pride, however, was Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” speech. In his book, Gallico wrote that Gehrig “was the living dead, and this was his funeral.” Gehrig’s speech, Sandomir writes “remains unmatched as a piece of athletic oratory” nearly 80 years after it was delivered and remains “a significant element of his soulful legacy.” Goldwyn, however, had Gehrig’s immortal line — “the luckiest man on the face of the earth”— placed at the end of his speech, rather than the second sentence where it actually happened. While a full version of the speech does not exist in print (although Eleanor Gehrig claimed to help write it), it was “great one, notable for its power, structure, generosity and modesty,” Sandomir writes. It didn’t matter that the speech was inaccurately portrayed in the film. To this day, the speech Cooper uttered in Pride is what we remember about Gehrig. He took the character of the unassuming slugger and made it his own. “Lou seems to have become more Gary Cooper than Lou Gehrig but I suppose they had to do that, Gallico wrote to Eleanor Gehrig midway through the film’s production. “I think he still comes out a very lovely character.” “Cooper’s last words as Gehrig were clearly his most enduring,” Sandomir writes. “Not only for their resonance over three generations, but for their uniqueness.” Sandomir writes about Pride with no prejudice. It’s a clear-eyed look at a film classic that has left most of us misty-eyed through the years. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed