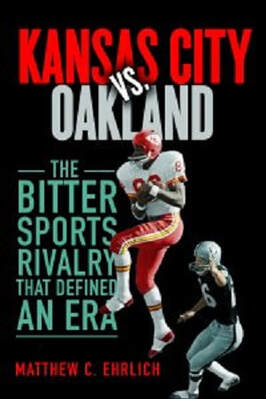

Let’s start with a book from last fall by Matthew C. Ehrlich, a professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Ehrlich takes a look at the rivalry between the cities of Kansas City and Oakland, particularly in sports, in his latest book, Kansas City vs. Oakland: The Bitter Sports Rivalry that Defined an Era (University of Illinois Press; paperback; $19.95; 240 pages).

The rivalry between Kansas City and Oakland was one of pro football’s best during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Both teams had wide-open offenses bolstered by hard-hitting defenses.

The Chiefs were the first American Football League representative in the Super Bowl, and Oakland followed suit the following season. Both teams lost to Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers, but the Chiefs would return to stun the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl IV. The Raiders were 1-2 in AFL title games and 1-5 in AFC Championship Games through the 1970s, winning Super Bowl XI.

In baseball, the two cities shared a special dislike. Kansas City felt like a jilted lover after the Athletics, who had been mediocre for a dozen years, fled west to Oakland after the 1967 season and then won three straight World Series titles from 1972 to 1974. Then the expansion Royals, who debuted in 1969, challenged the A’s for supremacy in the American League West during the mid-1970s, with Kansas City eventually gaining the upper hand.

Both cities carried a chip on their shoulders, and an inferiority complex to boot. Like their teams, Kansas City and Oakland wanted to be taken seriously, and civic leaders believed sports was the first step toward legitimacy. So did the sports editors of the newspapers in both cities, who pushed hard to gain franchises. In particular, Joe McGuff of The Kansas City Star was instrumental in securing the expansion Royals after the Athletics headed west.

“For Oakland, the problem always had been that it was not San Francisco,” Ehrlich writes. Kansas City, meanwhile, desperately wanted to shed the image of being a cow town with “corn-fed girls and good ole boys.”

Kansas City vs. Oakland is a scholarly work, with excellent research and detailed notes. There are five chapters and a conclusion — the actual text is 180 pages long, but the notes cover an additional 41 pages — but Ehrlich packs a lot of information into his work. Being a scholar, Ehrlich uses his introduction like a syllabus, to tell the reader what to expect.

The book might be scholarly, but the prose is not stuffy. Ehrlich does not talk down to his audience and shows his sports knowledge. He enjoys football and baseball and has ties to Kansas City, where he grew up. His father was an urban historian, who in 1979 published an architectural history of Kansas City.

Ehrlich knows media, working in radio while he was in college. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1983 from the University of Missouri and earned his master’s at the University of Kansas in 1987.

For his 1991 doctorate at Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Ehrlich wrote “Competition in Local TV News: Ritual, Enactment, and Ideology.” His published mainstream works since then were also media-based, including Journalism in the Movies in 2005 and with Radio Utopia: Postwar Audio Documentary in the Public Interest published in 2011. In 2015, Ehrlich teamed with University of Southern California journalism professor Joe Saltzman to produce Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture. This is a living document, as there is an online database connected with this work that references more than 90,000 items about journalists, news media and public relations professionals.

Ehrlich notes that Kansas City vs. Oakland “broadly addresses” the rivalry between the two cities from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s. So while sports are a starting point, it is not the total focus of Ehrlich’s work. The time frame of this book also was a time of sweeping social and political change.

Racism was a national issue during the 1960s and ’70s, and both Kansas City and Oakland struggled. Kansas City experienced “white flight” to the suburbs as the racial makeup of the inner city changed. In the words of one Kansas City sportswriter, Ehrlich writes, going to old Municipal Stadium was viewed as a place where fans could end up “with missing teeth and missing pocketbooks.”

In Oakland, a citizens group tried to organize a three-day boycott of the city’s schools in 1966, Ehrlich writes. The protest, aimed to expose the inequitable conditions between the inner city and affluent neighborhoods, would deteriorate into violence.

Both cities would construct gleaming new stadiums that were situated in the suburbs, making it difficult for minorities to attend. Some disgruntled citizens believed the money could have been better spent on schools and other services, rather than propping up sports franchises.

Ehrlich also focuses on urban regeneration, including Oakland’s ambitious City Center project, touted as “a major urban retailing, office, hotel and public open-space complex” that would create jobs and bring people into the downtown area. Those ambitions were unrealistic, Ehrlich writes.

However, the sports rivalry is what carries Kansas City vs. Oakland, and Ehrlich has some colorful personalities to draw from. Charlie O. Finley had connections to both cities because of the Athletics, once holding Kansas City’s heart “in the palm of his hand” after becoming owner because of his promotional skills — he got the Beatles to add a date to their 1964 tour so they could play in Kansas City, for example.

But Finley’s battles with city leaders over stadium issues quickly soured that relationship. Meanwhile, the Raiders had swagger and oozed toughness from the Oakland Coliseum, from owner Al Davis down to the water boy. Journalist Hunter S. Thompson once said Davis made Darth Vader “look like a wimp” — and he was right. Both teams could have fit the description of Athletics outfielder Joe Rudi, who said his squad looked like “a biker gang on a three-day bender.”

While Lamar Hunt, who owned the Chiefs, was a quiet man who helped found the AFL, his coach, Hank Stram, was ebullient and cocky. Stram was miked up during Super Bowl IV, and his glee after calling a 65 Toss Power Trap running play that allowed Mike Garrett to score a touchdown remains an NFL Films Classic. Hunt had moved the franchise from Dallas to Kansas City after the 1962 season, reasoning (correctly) he would not be able to compete against the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys.

Other larger than life personalities Ehrlich mentions include George Brett, Reggie Jackson, Willie Lanier, Daryle Lamonica, Ewing Kauffman and John Madden.

Ehrlich, who has been influenced by the writings of Jim Bouton (Ball Four), David Maraniss (When Pride Still Mattered) and McGuff (Winning It All), gives readers a detailed, absorbing look at the teams and players pleased fans in Kansas City and Oakland during a tumultuous decade.

The Chiefs returned to the pinnacle of pro football by winning Super Bowl LIV in February, and the Royals won the World Series in 2015 after a 30-year hiatus. The Raiders are moving to Las Vegas for the 2020 season, but the Athletics remain in Oakland and have made the postseason nine times since 2000. While Oakland has not won a Fall Classic since 1989 — fittingly, defeating the San Francisco Giants — the memories of those glory days of the 1970s remain.

Ehrlich does a nice job of meshing the stories of both cities and their franchises together.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed