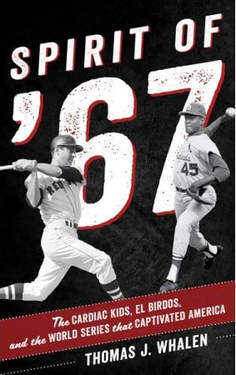

The 1968 and 1969 baseball seasons represented a line of demarcation for the sport. The 1968 season would be known as “the year of the pitcher” and the final gasp for 10-team leagues. The major leagues would expand by four teams in 1969, and divisional play was introduced.

In terms of leadership, baseball replaced its nondescript and ineffective commissioner with a man who would become one of the game’s most controversial leaders. Through Marvin Miller, the players were beginning to bargain effectively with the owners, and the game mirrored the cultural transformations that were taking place in the United States during the late 1960s.

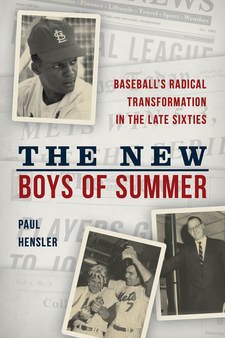

“This was a volatile era during which visions of a better America were thought to have vanished, and a time when the world as a whole was jolted by unrest,” baseball historian Paul Hensler writes in his second book. In The New Boys of Summer: Baseball’s Radical Transformation in the Late Sixties (Rowman & Littlefield; hardback; $39.95) captures the essence of baseball in a turbulent time in his new book. Hensler, who owns a master’s degree in history, takes the reader into the dugouts and boardrooms, providing a careful, richly detailed narrative.

Hensler is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research and wrote the book The American League in Transition, 1965-1975: How Competition Thrived When the Yankees Didn’t in 2012. He also has published several articles for SABR and for Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture.

Fans of baseball history will enjoy the percolating issues that Hensler brings to the surface as Major League Baseball approached its centennial in 1969. Baseball was on the verge of expansion in 1968, and Hensler guides the reader through the tangled actions that finally landed teams in Kansas City, Montreal, San Diego and Seattle.

Baseball traditionalists may have cringed at the idea of divisions, but owners like Minnesota’s Calvin Griffith saw the value of “better opportunities for profit” when the number of losers could be minimized, and more teams could vie for a spot in the World Series.

Hensler presents a very interesting proposal that was floated before expansion — three “major’ leagues of eight teams apiece, with interleague play to supplement the schedule. It was groundbreaking, fascinating, would have created natural rivalries — but it never happened. Interleague would become a reality nearly three decades later.

Hensler also strips away the emotions and bias that have surrounded Bowie Kuhn as the compromise candidate who became commissioner in 1969. The owners’ sacking of William D. “Spike” Eckert and installation of Kuhn turned out to be a fortuitous move. It provided, Hensler writes, “a vivid contrast of leadership style and an ability to move the game forward.” Kuhn’s hiring would become “a critical turning point” in baseball history. Baseball went from the unknown soldier (Eckert) to the unknown lawyer (Kuhn).

Say what you will about Kuhn — I believe that Kuhn’s enshrinement in the Hall of Fame while Marvin Miller has been excluded is one of the game’s inexcusable sins — but he was the right man at the right time for baseball. There is no question that Kuhn loved the game, and though he would be ridiculed later for his “best interests in baseball” mantra, he was still on solid footing in 1969.

Miller has been lauded for his work in making baseball’s union the most powerful labor force in sports, but when he first took over his task “was fraught initially with the arduous chore” of winning over the players. While Miller lacked charisma, he made up for it by being “gifted with an ability to communicate and lead.”

Hensler also delves into racial turmoil, how Major League Baseball botched its reactions to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy and the dawn of cookie-cutter stadiums. Plus, he writes about the rise of statisticians, who rightfully could be called the ancestors of today’s SABR members.

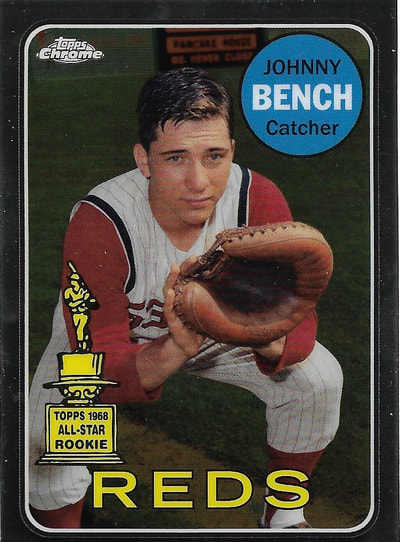

There was good baseball, too. The New York Mets capped a new era of divisional play by shocking the experts and rolling to a World Series title in 1969. The old guard of baseball was retiring, replaced by a new breed of players that questioned authority and insisted on expressing their own individuality.

Hensler’s research is extensive and varied. Happily, he dips deeply into Jim Bouton’s classic baseball diary of the 1969 season, Ball Four, and many other books. He also utilizes documents, periodicals, articles, baseball team publications, special collections and websites. His bibliography is a diverse cross-section of sports, politics, culture, social awareness and history. Hensler provides plenty of background as he introduces each topic, giving the reader a firm basis to understand the events of 1968 and 1969.

It is important to take all the elements Hensler writes about as one tapestry, rather than distinct pieces of cloth. There is no singular event that could characterize the baseball seasons of 1968 and 1969. Rather, it was a combination of factors that allowed baseball to move out of the doldrums and back into competition with other sports, particularly pro football. It would take time, though.

“American society and culture were in flux,” Hensler writes, “and baseball was affected by the changes in a country growing ever restive with a stubborn war in Southeast Asia.”

Those changes in American politics and culture were also felt on the baseball diamond. Hensler does a marvelous job of blending all the issues together in a coherent, entertaining narrative.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed