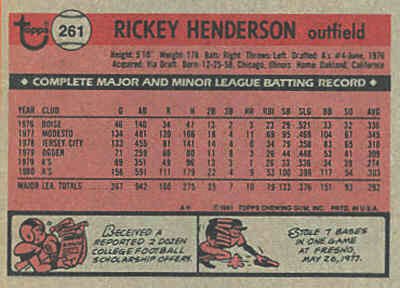

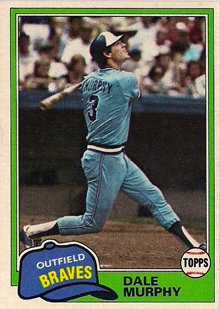

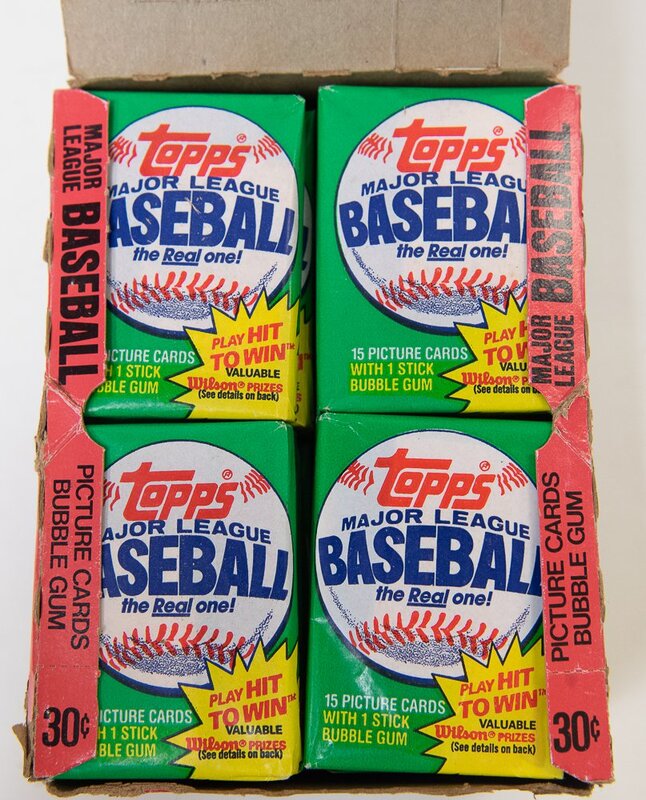

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1981-topps-baseball-capped-a-new-era-for-cards/

|

Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1981 Topps baseball set and the legal wrangling that allowed Fleer and Donruss to produce cards: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1981-topps-baseball-capped-a-new-era-for-cards/

0 Comments

Here's a podcast I did on the New Books Network with Alexander Barnes, co-author of Play Ball! Doughboys and Baseball during the Great War.

https://newbooksnetwork.com/alexander-barnes-play-ball-doughboys-and-baseball-during-the-great-war-schiffer-publishing-2019/

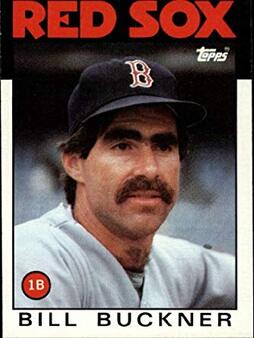

Baseball can be a cruel game. One play, or one game, can define a player’s career. Bobby Thomson hit a game-winning home run in the deciding game of the 1951 National League playoffs to give the New York Giants the pennant. Reggie Jackson hit three home runs in Game 6 of the 1977 World Series to punch his ticket as “Mr. October.” And Bill Buckner let a ground ball go through his legs in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. Buckner, who died Monday from Lewy Body Dementia, was 69. He had 2,715 hits over a 22-year career and won the 1980 N.L. batting title when he hit .324 with the Chicago Cubs. Fun fact: Buckner was playing left field for the Los Angeles Dodgers the night Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record with No. 715. But that one play ... “Little roller up along first … behind the bag!” NBC announcer Vin Scully yelled. “It gets through Buckner. Here comes (Ray) Knight and the Mets win it!”

The Mets won Game 6 after being down to its last strike moments earlier. As Knight celebrated with his hands to his head as he scored the winning run, Buckner trudged off the field.

The Mets would win Game 7, and Buckner would be branded with goat horns that had been passed down from Fred Merkle and Mickey Owen. Buckner deserved better, but he never seemed to get a fair shake after that error. Red Sox fans equated Buckner with the Curse of the Bambino, as Boston had come so close a few times to win its first World Series title since 1918. “One bad day,” Mike Sowell wrote in his 1995 book, One Pitch Away. “No one is perfect.” Buckner and Wilson would be tied together forever, much like Thompson was with Ralph Branca, who threw him the pitch that became "The Shot Heard 'Round the World." Three things people tend to forget about that iconic play in Game 6. One, if Bob Stanley does not throw a wild pitch to Mookie Wilson several pitches before Buckner’s error, Kevin Mitchell doesn’t score the tying run. Two, if Buckner makes the play and gets Wilson out, the game remains tied. There was no guarantee who would win the game. And three, even if Buckner fields the ball cleanly, it was not a given he could beat Wilson to first or flip the ball in time to Stanley, who was slow breaking to first base to cover the bag,

Even baseball card companies appeared to get into the act. Buckner’s 1990 Upper Deck card shows him crouched in his position at first base, with the giant hole of a stadium tarp in the background, between his legs.

An E-3 if there ever was one. Perhaps Buckner should not have even been in the game at Shea Stadium at the end of Game 6 because he had come up lame as the playoffs began. Perhaps Red Sox manager John McNamara was a sentimental guy, even though he denied it during a 2011 show on the MLB Network during a retrospective program about the 1986 World Series. Dave Stapleton certainly thought McNamara used his heart, and not his head. Stapleton had been used as a defensive replacement for Buckner at first base at the end of every postseason victory in 1986. But McNamara left Buckner to finish off Game 6. Holding a 5-3 lead heading into the bottom of the 10th, it seemed like a safe bet. It wasn’t. “If the truth was known -- and I don’t know if anybody would admit it, but most people know it -- all they were trying to do was leave Buckner out there so he could be on the field to celebrate when we won the game,” Stapleton told Sowell. “But my contention always was you don’t get to celebrate until you win it.” Sixteen years later, on the MLB Network show, McNamara denied sentimentality played a part. — Bobby Valentine (@BobbyValentine) May 27, 2019

Buckner was the best first baseman I had,” McNamara said. “And Dave Stapleton has taken enough shots at me since that he didn’t get in that ballgame, but Dave Stapleton’s nickname was Shakey. And you know what that implies. I didn’t want him playing first base to end that game, and it was not any sentimental thing that I had for Billy Buck.”

Buckner was released by the Red Sox in July 1987. He later played for the Angels and Royals before returning to the Red Sox as a free agent in 1990. Buckner retired with a .289 lifetime average. His numbers are similar in some categories to Harold Baines, elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee and scheduled for enshrinement later this summer. Both played the same number of seasons and had the same lifetime batting average. But to be fair, Baines held an edge over Buckner in home runs (384-174), RBI (1,628-1,208), runs (1,299-1,077) and slugging percentage (.465-.4e08). Sometimes, there is a fine line between being very good and being great.

Buckner moved to Idaho and owned a cattle ranch after retirement. It was a nice change from Boston, where he remained under a microscope.

He stayed away from the Red Sox and refused to participate when the team celebrated the 20th anniversary of the 1986 American League championship team. But after the Red Sox won the World Series in 2007 -- the second one in four seasons after an 86-year drought -- Buckner returned to Fenway Park in 2008 to throw out a ceremonial first pitch.

“You go back and you could look at that (1986) series and point fingers in a whole bunch of different directions,” Buckner said at the time. “John McNamara’s taken a lot of heat. I don’t think that’s deserved.

“We did the best we could to win there and it just didn’t happen. I don’t feel that I deserved (the blame). And if I felt like it was my fault, I’d step up to the plate and say, ‘Hey, if I wasn’t here, the Red Sox would have won this thing.’ But I really can’t do that.” One player should not be defined by one play. Even as I write this, what am I focusing on? That slow ground ball. I can relate. As a first baseman in the Boynton Beach Senior Little League back in the early 1970s, I was playing first base. We were a mediocre team, but we were leading the first-place squad late in the game. There was one out and the bases were loaded when a batter hit a soft line drive toward me. The runners were moving, so I had a easy double play on my mind. My manager, Bob Pimm, later charitably said I lost the ball in the lights, but face it -- I blew the play. The ball skipped off the top of my glove and two runs scored. We lost by a run. Pimm said something to the effect of “Don’t worry babe, we’ll get ’em next time.” My manager called everyone “babe,” including his wife, kids and perhaps the garbage man. More than a decade later, I felt Bill Buckner’s pain. It was a pain he never could escape. Sowell tells the story of Buckner going to the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in the fall of 1988 for treatment on his left ankle. The nurse picked up his chart and seemed puzzled. Then, she remembered. “Hey, aren’t you the guy that let that ball go between your legs?” she asked. RIP, Bill Buckner. You were more than just a negative footnote in baseball history.

Bart Starr was the consummate quarterback for the NFL during the 1960s. He ran the Green Bay Packers’ offense with mechanical precision, relying on Vince Lombardi’s “run to daylight” philosophy while sprinkling in pinpoint passing. He was simple, straightforward, and elegant.

The legendary Green Bay Packers quarterback died Sunday in Birmingham, Alabama, after several years of poor health. He was 85. Starr led the Packers to five NFL championships and was the starting quarterback and most valuable player when the Green Bay Packers won the first two Super Bowls. He also engineered arguably the most famous play in Packers history, a 1-yard quarterback sneak that gave Green Bay a 21-17 victory against the Dallas Cowboys in the “Ice Bowl” on Dec. 31, 1967. “Thirty-one wedge and I’ll carry the ball,” Starr said in the huddle. There were 13 seconds left when Starr stretched and landed in the end zone to clinch the Packers’ fifth NFL championship, thanks to a crushing block by guard Jerry Kramer. “It was the most beautiful sight in the world, seeing Bart lying down next to me and seeing the referee in front of me, his arms over his head, signaling the touchdown,” Kramer wrote in Instant Replay, his diary of the 1967 season.

Starr was drafted in the 17th round of the 1956 NFL draft, the 200th pick overall. He played for the Packers from 1956 to 1971 and threw for 24,718 yards and 152 touchdowns and was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1977. The Packers retired his No. 15 uniform in November 1973.

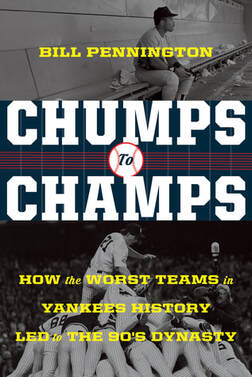

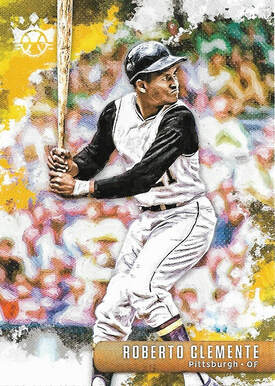

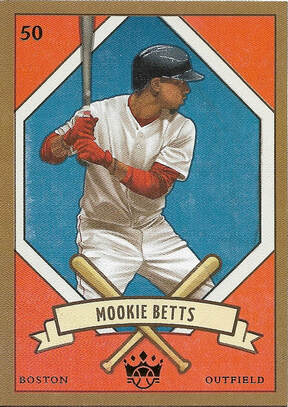

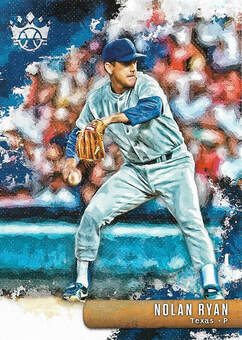

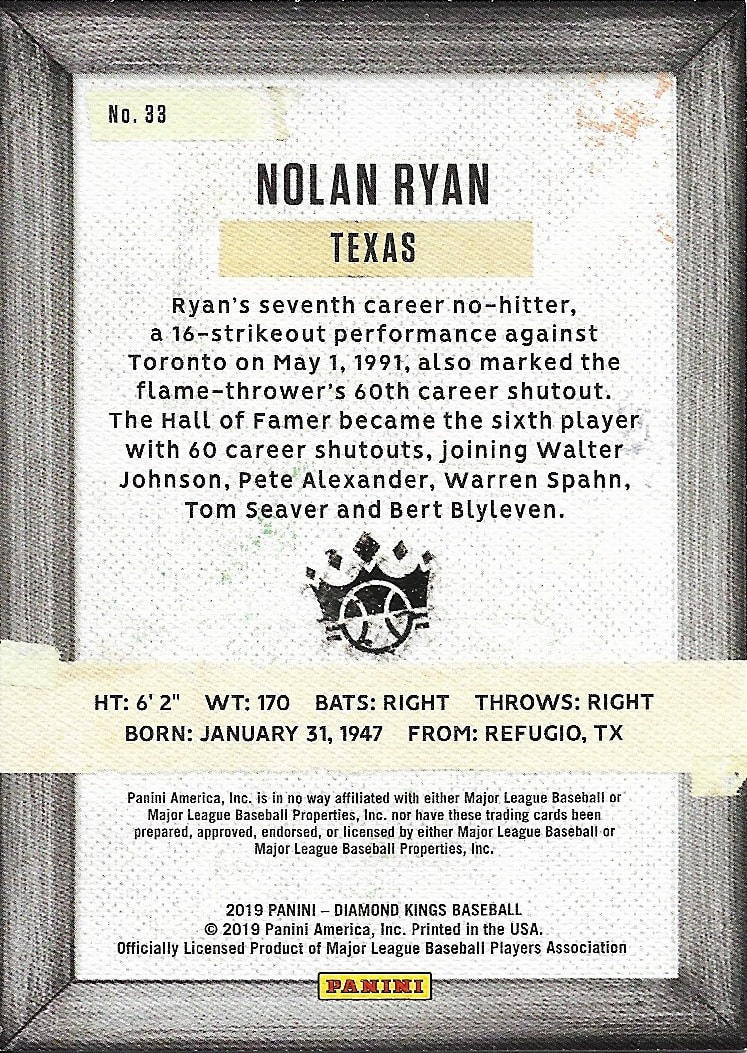

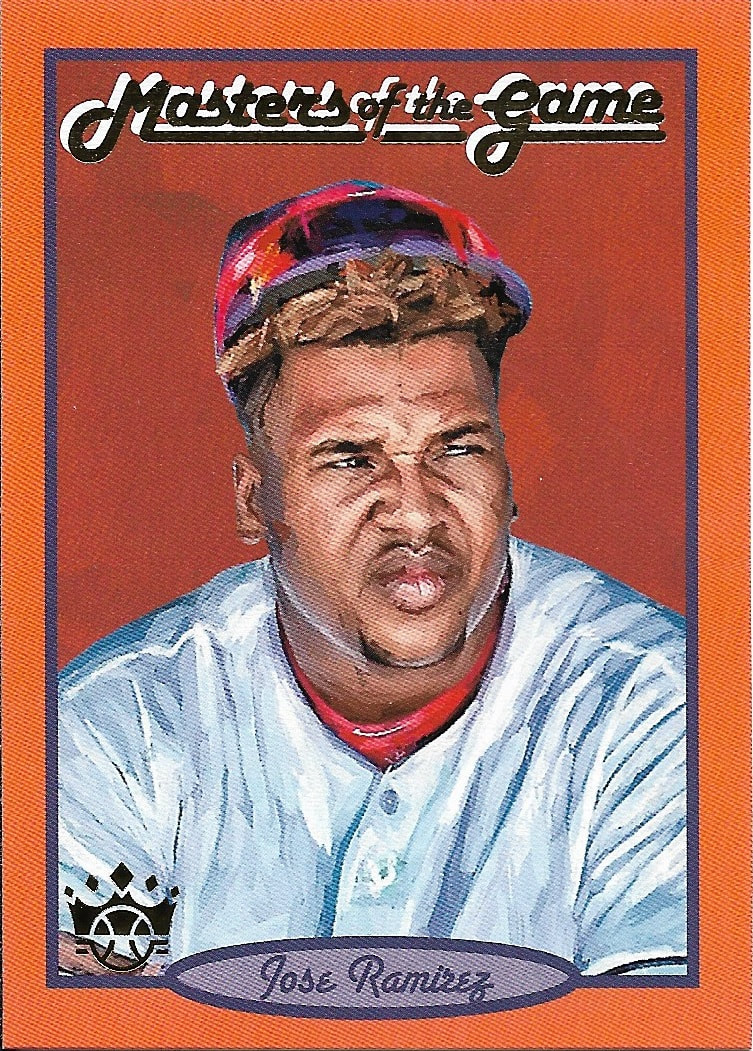

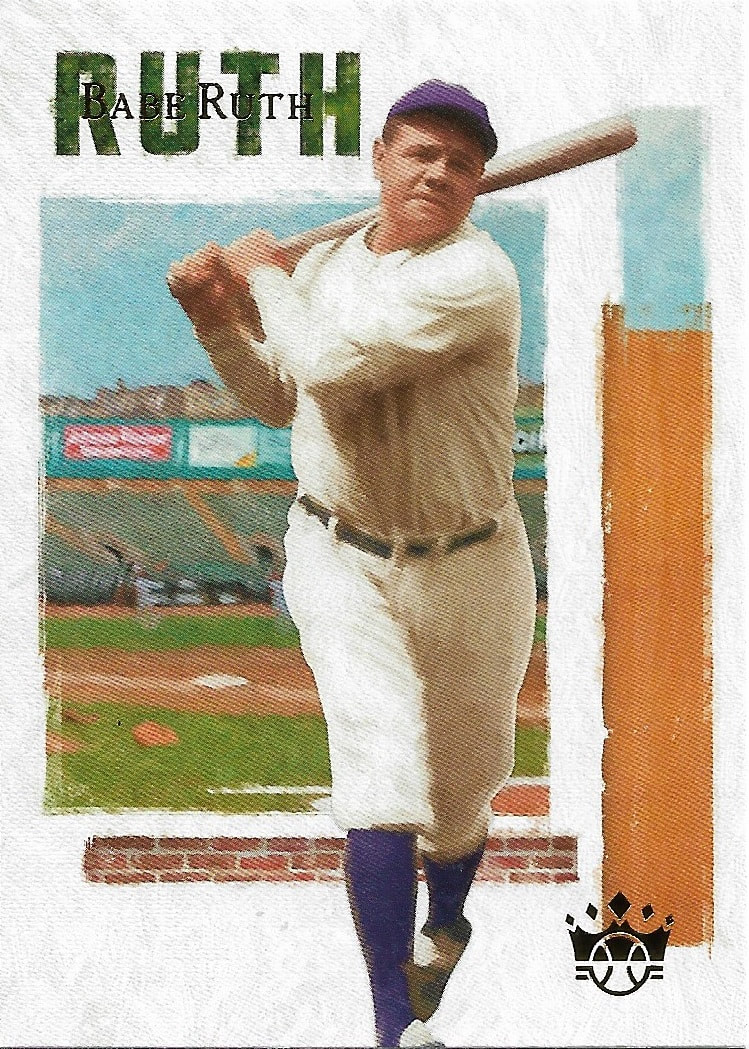

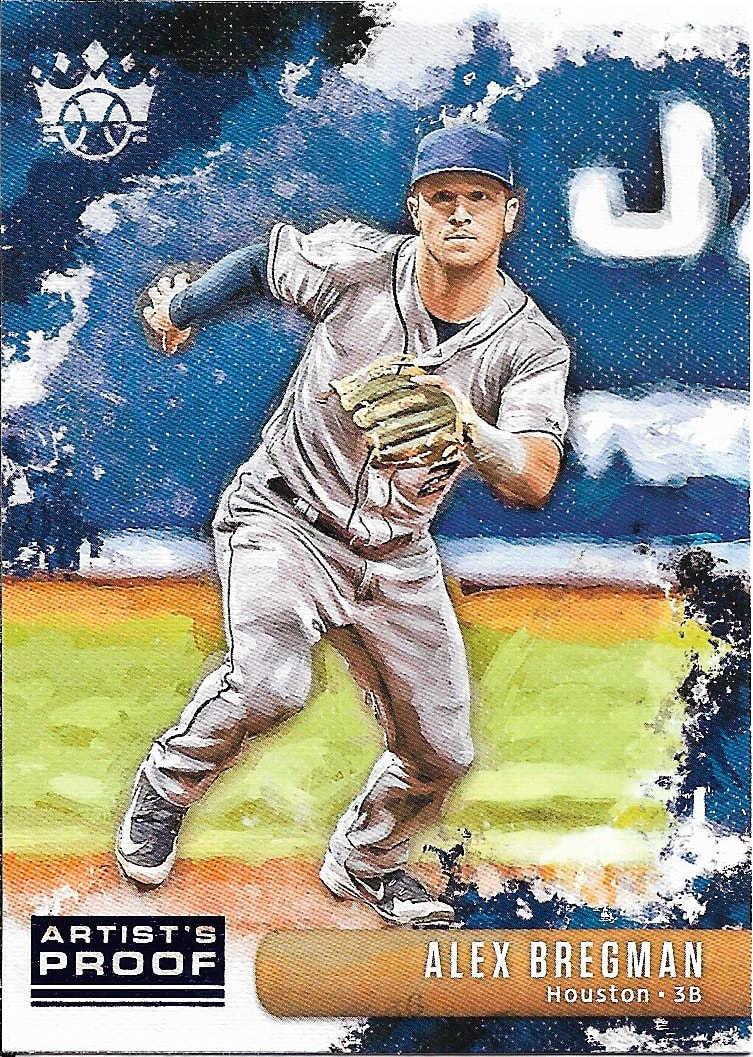

Starr was a soft-spoken leader, but stern. In Instant Replay, Kramer said Starr raising his voice was a rare occasion. When Starr was hit hard by Pittsburgh Steelers defensive end Lloyd Voss in a 1967 exhibition game, he turned to reserve tackle Steve Wright, who let Voss through, and let him have it. “If I see that guy in here once more tonight, I’m not going to kick him in the can,” Starr said in the huddle. “I’m going to kick you in the can, right in front of 52,000 people.” “For Bart, that was very strong talk,” Kramer wrote. Starr came into his own in 1960, when he led the Packers to the NFL championship game, when Green Bay lost to Philadelphia. Starr then led Green Bay to NFL titles in 1961, 1962, 1965, 1966 and 1967. Always the consummate pro, Starr was never flashy and did not have gaudy statistics, but he was consistent and rarely made a mistake. Starr later served as Green Bay’s coach from 1975 to 1983, compiling a 52-76-3 record. He was no Lombardi, but his will to win was just as intense. The Packers simply did not have the personnel during that nine-year stretch. But it wasn’t for a lack of trying. “The harder you work,” coach Vince Lombardi told his players when he took over in Green Bay in 1959,” the harder it is to surrender.” That was Bart Starr’s credo.  For haters of the New York Yankees, it was the best of times. And for fans of the Bronx Bombers, it was the worst of times. After a resurgence in the late 1970s. the Yankees entered a dry patch. From 1982 through 1994 they did not reach the playoffs and were just plain awful from 1988 to 1992, when they finished in fifth place in the American League East four times and in seventh (last) place in 1990. Free agents came and went, and so did managers. The Yankees’ minor league system was stripped bare because team owner George Steinbrenner employed a win-now mentality. It wasn’t working. The ultimate indignity came when Andy Hawkins took a no-hitter into the bottom of the eighth inning on July 1, 1990. Hawkins was mowing down the Chicago White Sox, but two walks and two errors resulted in a 4-0 loss. Hawkins had his eight-inning no-hitter — and even that was taken away thanks to a new rule the next season — but the Yankees lost. That is how Bill Pennington opens his latest book, From Chumps to Champs: How the Worst Teams in Yankees History Led to the ’90s Dynasty (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; 351 pages; $28). Pennington, who has been with The New York Times since 1997, was a beat writer covering the Yankees during the 1980s and 1990s with the Bergen Record in northern New Jersey. His 2015 biography, Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius, was full of insights thanks to Pennington’s job on the Yankees beat. From Champs to Chumps is a story Pennington is qualified to write, since he witnessed the Yankees’ rise from the dust. There are two major heroes in this book — Yankees general manager Gene Michael is one. “Stick” drafted well and restocked the team’s minor league system, bringing along players like Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Mariano Rivera and Jorge Posada. These players would become the “Core Four,” who led New York to three World Series titles in five seasons. Pennington also gives the reader a blow-by-blow description of the draft that brought Jeter to the Yankees, which is a tantalizing story of “what if.” Michael also brought veteran leadership to the team, trading for the intense, hot-tempered Paul O’Neill. And he resisted overtures to trade his Core Four or Bernie Williams, rightfully believing he had a solid group needed seasoning, not tampering. The second hero in Pennington’s book is Buck Showalter, who managed the Yankees from 1992 to 1995. Michael brought in the players, and Showalter used them as “culture creators,” who did things the Yankee Way. “You can talk all about stats and analytics, and I get that,” Showalter tells Pennington. “But you can’t measure how to build the most productive team culture. And that gets lost. Or it can. “We tried to make sure it didn’t.” Managers can talk about culture, but they still have to field a lineup. Inevitably, some players won’t he happy platooning, or sitting on the bench. Pennington shows how Showalter’s attention to detail — no matter how trivial —helped build the culture he wanted. After filling out his lineup card, Showalter listed the non-player members of the team in alphabetical order “so that no one would feel slighted.” “Every player looks at the lineup card closely,” Showalter tells Pennington. “When I was playing, if I wasn’t starting, I’d look at the list of reserves. If my name was listed at the bottom I’d say to myself, ‘I’m the last person on the manager’s mind.’” That kind of routine helped Showalter gain trust and respect, and it is the kind of nugget Pennington uses to show how the Yankees’ culture was indeed changing. That attention to detail also translated into the future. Steinbrenner once questioned why Showalter held Jimmy Key’s start back a day, Pennington writes. Showalter explained the umpire the following day called “a lot of low strikes,” which would make Key’s assortment of sinkers, sliders and low fastballs that much more effective. Showalter also spruced up the clubhouse with better food, better facilities and a family atmosphere. There is one more hero in this book, albeit a reluctant one. For all that Michael and Showalter did to build the Yankees up from the dust, it was the banishment of Steinbrenner that enabled them to nurture the team and put the pieces together for the dynasty of the late 1990s. Steinbrenner took a lifetime ban, rather than a suspension, because he wanted to be a member of the U.S. Olympic Committee and viewed the word “suspended” as a stain on his legacy, Pennington writes. It led to a bizarre ban that even had Commissioner Fay Vincent shaking his head, leaving him “dumbfounded.” Pennington shows how, with Steinbrenner out of the picture, the Yankees were able to draft players they needed and trade for key veterans. Given Steinbrenner’s penchant for impatience, it is unlikely that Rivera or Pettitte would have remained on the team if he was still involved in day-to-day operations, for example. Jeter might have been gone, too. But Michael would not have it that way, and the Yankees prospered because of his vision. Pennington is thorough in his research, and he makes the book come alive through his interviews with 125 people who went on the record — he notes that some team officials asked to remain anonymous, so the number of people interviewed is closer to 140. Much of the reporting in this book, Pennington concedes, was made possible by the professional relationships he established as a beat reporter and columnist, “even if I did not know it would someday lead to a book.” He was delighted to discover that, when he began his research in 2016 and started interviewing the principal subjects for the book, their memories were “crisp, potent and edifying.” The book has a personal touch because Pennington was there to see it, but he also fact-checked his memories through newspaper archives and the records at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. From Chumps to Champs is an entertaining book that digs into an era that most Yankees fans would like to forget. The dogged work of men like Michael and Showalter, however, yielded big results by the middle of the 1990s. While a strike prevented the Yankees from reaching the playoffs in 1994 and the team fell short against Seattle in the 1995 playoffs, the pieces were in place. The next eight years would produce six American League pennants and four World Series titles. Pennington’s research and insight serves as a prelude to those years of glory.  Panini America’s Diamond Kings baseball set is like a watercolor painting come to life. With some interesting shots and an offbeat selection of greats, the set definitely should have some appeal for collectors. There are 150 cards in the base set, with the final 50 cards being short prints. The base set has frame parallels in blue, plum, red and a 1/1 black. Artist’s Proof parallels can be found in Artist Proof, Artist Proof blue and Artist Proof Masterpiece. The design for the base set is vertical on the card fronts and backs. The watercolor look mostly comes from the background behind the player on the card front. The artwork of the players in action is intricate and expressive A Diamond Kings logo is perched in the upper left-hand corner of the card. Because Panini does not have a license with Major League Baseball or Major League Baseball Properties, Inc., team logos are not allowed on the card The team name is also not mentioned, but the city name is.  The card backs are ringed by a brown frame, with the player’s name and an eight-line biographical sketch dominating the top half of the card. A Diamond Kings logo sits in the middle of the card, with vital statistics underneath. A blaster box contains six packs, with five cards to a pack. There is an additional five-card pack with special Babe Ruth cards, Artist’s Proofs and framed parallels. There is an average of one insert per “regular” pack. The blaster I opened had 23 base cards and a Nolan Ryan variation. Not only is the photo of Ryan different than the base set, but the frame is the back is gray; in the base set the frames on the card backs are brown. What is interesting about this set is the checklist, which includes Hall of Famers like Satchel Paige, Roberto Clemente, Al Simmons, Yogi Berra, Walter Alston a and Vladimir Guerrero. Those are some of the cards of old-timers I pulled, along with Carl Erskine. Twenty-four of the first 30 cards in the Diamond Kings checklist are Hall of Famers, and the other six include Erskine, Roger Maris, Eddie Stanky, Smoky Joe Wood, Shoeless Joe Jackson and Charlie Keller.  Not having an official license allows Panini to use Jackson in its base set and as part of its insert subsets. The inserts I pulled included a Mookie Betts card from the 25-card DK 205 Set, a Masters of the Game insert of Jose Ramirez, a Squires insert of Miguel Andujar and a pair Team Heroes (Adrian Beltre and Ramirez). There also was a Diamond Kings card of Jackson, which is part of a five-card set. The special pack yielded framed cards of Alston and Shohei Ohtani, an Artist’s Proof card of Alex Bregman, and two Babe Ruth Collection inserts that are Target exclusives. The 2019 Diamond Kings set also offers autographs and relic cards, but most likely those will pop up in hobby boxes. I never rule it out for blaster boxes, but it is certainly rare. Regardless, the base set is easy to collect – although the short prints will be a challenge — and the player selection is nice. That’s a good combination. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Huggins and Scott's Spring 2019 auction:

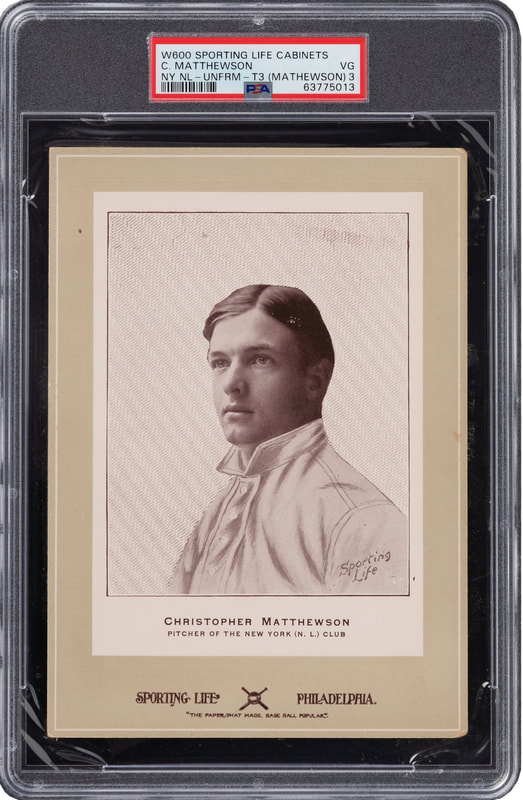

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/christy-mathewson-nolan-ryan-items-highlight-huggins-and-scott-spring-auction/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed