Virtually ignored by Hall of Fame voters from 1937 to 1960 — his best showing was in 1958, when he appeared on 16.2% of the ballots (43 votes) in his 14th year of eligibility — Bancroft was enshrined in Cooperstown in 1971 by the Veterans Committee. Critics point to cronyism by Frank Frisch, his former teammate with the New York Giants who was on the committee. Frisch also spearheaded the election of four other teammates into the Hall — Jesse “Pop” Haines (1970), Chick Hafey (1971), Ross Youngs (1972) and George Kelly (1973).

The Hall of Fame has never put a premium on fielding, but the Veterans Committee got it right with Bancroft. He led the National League in assists and double plays three times, topped the circuit in putouts four times, led the league in fielding twice and was in the top-10 among shortstops 10 times. He still holds the record for most chances in a season by a shortstop (984 in 1922). There were no Gold Gloves awarded when Bancroft played, but he certainly would have snagged a few.

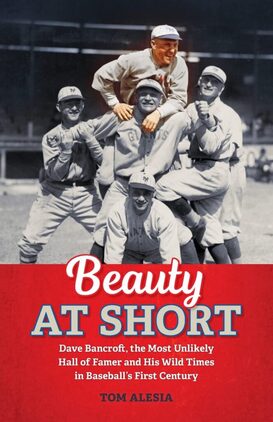

Which begs the question again — why is Bancroft in the Hall of Fame? Author Tom Alesia presents a persuasive argument in his book, Beauty at Short: Dave Bancroft, the Most Unlikely Hall of Famer and His Wild Times in Baseball’s First Century (Grissom Press; $9.39; paperback; 169 pages).

Alesia’s decision to write a biography on Bancroft was just as unlikely as the shortstop’s election into the Hall of Fame. Alesia was vacationing in northwestern Wisconsin in 2011 and checked the internet for interesting tidbits about the area. That is when he discovered that Bancroft and his wife were buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Superior.

That began a “labor of love” that led Alesia to add another interesting chapter to his writing career. It also rekindled the affection Bancroft’s hometown of Sioux City had for its native son. On July 1 there will be a Dave Bancroft T-shirt night for the American Association’s Sioux City Explorers, and Alesia will throw out the first pitch. The Dave Bancroft Fan Services pavilion will also be dedicated at Lewis and Clark Park.

Tom Alesia's blog, "Tom Write Turns" covers many subjects, including sports. He researched many newspapers while researching Dave Bancroft's life.

Tom Alesia's blog, "Tom Write Turns" covers many subjects, including sports. He researched many newspapers while researching Dave Bancroft's life. Alesia is now based in Madison, Wisconsin, where he teaches at the Indian Mound Middle School in nearby McFarland.

Bancroft presented a different challenge for Alesia. How does one unearth information about a man who played more than a century ago and died almost 50 years ago?

“Built along the lines of a (Rabbit) Maranville, he is fast and covers a lot of ground,” the York Dispatch reported about Bancroft, who was a rookie trying to crack the lineup with the Philadelphia Phillies during the spring of 1915. Bancroft played deep and was a marvel at “covering loam,” according to the newspaper’s colorful writing style of the time.

Alesia, who has written pieces for newspapers through the years, did plenty of research through publications. He found material from 167 different newspapers, 10 magazines and news wire services, 22 websites or blogs and 12 other reference sites.

And then there is that nickname, “Beauty.” There is some speculation that Bancroft got the nickname for his penchant of saying “beauty” after a particularly good play or pitch.

Alesia notes that the nickname was first used in a newspaper story by a New York newspaper about a week after Bancroft joined the Giants. The origin remains hazy, even though “Beauty” is included in Bancroft’s Hall of Fame plaque.

In four long interviews from the 1950s until 1970, Bancroft never mentioned how he got the nickname.

“If it bothered him, he never indicated that,” Alesia writes.

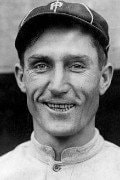

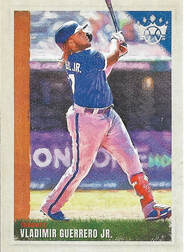

Dave Bancroft.

Dave Bancroft. Bancroft’s hitting was certainly not a thing of beauty. Cleveland scout Robert Gilks first watched Bancroft play for the Superior Red Sox in 1912 and pronounced that the young infielder “is not a hitter,” Gilks would say.

Bancroft learned to become a switch-hitter, and from 1918 until 1926 he never batted below .265. He connected for six singles in a nine-inning game and scored a run in four consecutive innings. Bancroft later became an early advocate for what would become the designated hitter.

Bancroft helped the Phillies to their first National League pennant in 1915 and was named team captain five years later. However, a spat with manager Gavvy Cravath in 1920 led to the shortstop’s trade to the Giants. That was a welcome change for Bancroft, who helped the Giants win pennants from 1921 to 1923.

Alesia recounts an amusing story when Bancroft joined the Giants. Catcher Pancho Snyder approached the shortstop and began telling him the team’s signs.

“Why? Have they changed?” Bancroft said.

Bancroft would become the Giants’ team captain but was traded to the Boston Braves to become player-manager in 1924, Alesia writes, a position he held for four seasons. Bancroft had a 249-369-3 record in Boston, finishing fifth, seventh (twice) and eighth in the eight-team league.

Alesia brings up a notable fight involving Bancroft in 1927. Actually, it was a one-punch deal, when Pirates catcher Earl Smith leveled Bancroft, who was scoring on a double. The punch knocked Bancroft out, and Smith would be suspended and fined.

Alesia correctly notes that Smith, who starred on two pennant winners in Pittsburgh and played for the Braves when Bancroft managed in Boston during 1924, was “a career-long hothead.” He makes the point that when Smith died in June 1963, the Pittsburgh Press “published two sentences about his death.”

“The obit’s second sentence was about punching Bancroft,” Alesia writes.

Perhaps that is true, but two sentences about a key player on two pennant winners seemed odd. Smith was not a forgotten man in Pittsburgh, was he? I had to investigate.

The June 11, 1963, edition of the Press ran an obituary written by The Associated Press. The seven-paragraph story did not mention the Bancroft incident. The next day, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette sports editor Al Abrams led his column with memories of Smith and gave the Bancroft incident good play.

On June 13, 1963, the Pittsburgh Press ran a column by sports editor Chester L. Smith that led with Earl Smith but did not mention Bancroft.

Pie Traynor’s account of the fight, which Alesia references, came from an Abrams column in the Post-Gazette on June 21, 1963.

That is my only real criticism in this work.

The only other mistake I saw was when Alesia noted that only two players from the 1915 pennant winners —“(Christy) Mathewson and Cravath” — were included on the Phillies’ Wall of Fame. Certainly, Alesia meant Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Alesia takes the reader through the latter stages of Bancroft’s career, when he played two seasons with Brooklyn and returned to the Giants as a coach in 1930 (he did play in 10 games before retiring). Bancroft would substitute as manager for John McGraw when the “Little Napoleon” was ill, but he was passed over for the Giants job in favor of Bill Terry in 1932.

“Bancroft was considered too close to McGraw in style to replace him,” Alesia writes.

Bancroft had been mentioned as a managerial candidate for Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and the Chicago White Sox, but he was not hired.

He would manage at the minor league level in Minneapolis (1933), Sioux City (1936) and St. Cloud (1947).

From 1948 to 1951, Bancroft would manage three different teams in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League: the Chicago Colleens, South Bend Blue Sox and Battle Creek Belles. In 1949, he also managed a women’s team that barnstormed through Central America, South America and the Caribbean island nations.

After baseball, Bancroft worked in the business sector until he retired in 1956. Elected to the Hal of Fame in 1971, Bancroft was too ill to attend the induction ceremony. Cooperstown was the culmination of honors for Bancroft, who was inducted into the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame in 1954, followed by enshrinement in the Superior Hall of Fame (1964), the Sioux City Hall of Fame (1965) and the Duluth Hall of Fame (1971).

“He was a perfectionist in whatever he undertook,” columnist Dick Cullum of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune wrote after Bancroft’s death. “He dressed precisely, spoke precisely, played baseball precisely, and his home town loved him.”

Travis Jackson, the Hall of Famer who replaced Bancroft at shortstop for the New York Giants, never doubted for a minute who the better player was, Alesia writes.

“Listen, if you think I was good, you should have seen Bancroft,” Jackson said in 1967.

Thanks to Alesia and Beauty at Short, baseball fans can finally see why Bancroft deserves that plaque in Cooperstown.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed