Writers, editors, stringers, correspondents — I saw them all. When I joined the Tribune there were 63 full-time employees in the department. That does not include stringers. That number was considerably less when the paper was shuttered on May 3, 2016.

Stringers are the sports correspondents who contribute to the main section, covering games, writing features, and doing it as independent contractors. No benefits, and you have to track your pay to take out the proper amount of taxes.

Super correspondents, or “super corros,” got to cover some of the bigger events in support of the beat writers from time to time.

It can be a thankless job, but there is the lure of seeing your byline. It is like a narcotic. To this day, I still get chills when I see my byline on a story. After 40-plus years, it never gets old.

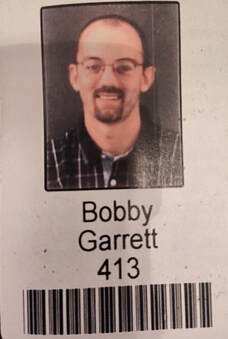

That’s what Garrett conveys in his sentimental look back at his journalism career. In Stringer (RGMG Publishing; $29.99; hardback; 166 pages), Garrett (we called him Bobby back then, but he returned to his formal name for legitimate reasons he explains in the book) looks back at his seven years as a correspondent and staff writer for the Tribune, the Sebring Daily News, Buccaneer magazine and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Garrett went from emptying trash cans at a Tribune bureau in Central Florida while working for his father’s janitorial service to writing more than 1,200 stories starting in October 1995.

Many who have a published a book note that writing it was “a labor of love,” or something like that. For Garrett, it was a labor — and not because he did not have anything to write. He couldn’t write — having “a booger of a disease” for more than a decade called ALS, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, forced him to use a dictating application to “speak” his memoirs.

And there is a lot to talk about.

He recalls his youth in Cocoa — not Cocoa Beach, don’t you dare say that, since the rivalry between the two Space Coast cities is keen — and living a mile from the Brevard Correctional Institute.

Garrett also discusses the unpredictability of sports, which gives all writers — seasoned pros or stringers — many different challenges.

It was fun to read about some of the characters Garrett encountered during his years at the Tribune, starting with Tom Ford. A veteran journalist who was once the Tribune’s lead beat writer for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Ford was versatile and wore many hats as a sports bureau chief to a sports copy editor at the main office. We worked together for several years as writer-editor and later as desk colleagues downtown — listening to Ford on the phone jousting with then-Bucs coach Ray Perkins was a treat. You did not have to hear Perkins’ end of the conversation to know what was going on.

But Garrett describes him perfectly, noting that Ford would take his glasses off the top of his head and perch them on his nose to read a story. He left out Ford’s penchant for tie-dye shirts, a Ric Flair hairdo and an ever-present yoga mat, but those are my memories and may not have been universal.

Other writers and editors Garrett describes in his anecdotes include Kevin Wells, Scott Carter, Scott Wallin, Pat Yasinskas, Brett McMurphy, Paul C. Smith, David Whitley, Erik Erlendsson, Dana Caldwell, Rozel Lee, Jason Davis and others.

I sort of feel like my old sports editor at the Tribune, the late, great Tom McEwen, who never had a problem with us correcting his grammar (he never met a comma he didn’t like, God love him) but admonished us not to cut out names from his column. Correct the spelling? Certainly. Just don’t delete the names.

“They are there for a reason,” Tom would say.

The names in Stringer are there for a reason. They helped shape the career of a young journalist.

For those who believe that it is easy to interview sports figures and turn in great stories on deadline, Garrett sets the record straight. Speaking with a famous athlete can be difficult even when you are an established writer, particularly when the questions provoke a testy response. Garrett notes that he was “gobsmacked” by the notion that he could call and speak with an NFL coach, like when then-Broncos coach Mike Shanahan returned a message and chatted about Wayne Peace, his quarterback pupil at the University of Florida in the early 1980s.

Garrett was facing similar pressures and performed well.

And then you were at the mercy of the sports desk. A bad headline could bring the wrath of coaches and parents upon the writer, who had nothing to do with it. And parents, Garrett writes, could be “your biggest advocate or your worst enemy.”

Garrett trots out the Tribune’s infamous “Glades Central makes road kill out of Robinson” headline, which, if memory serves, was from the 1997 Class 4A state football semifinal. It’s still cringeworthy 25 years later.

I was on the Tribune copy desk for 28 years, so I’ve written my share of good and bad headlines. That was not one of them, thank goodness.

Garrett sprinkles his book with passages from his more memorable writing efforts, from clinics for girls hockey to a piece about a boy with spina bifida who struck up a friendship with Bucs running back Mike Alstott. Or even a rodeo event in rural Arcadia called the Wildhorse Race, or a one-on-one interview with actor Jason Priestley.

Garrett also reminisces about his time writing for the Sebring Daily News, a small newspaper in Florida’s heartland. Sebring is nestled between orange groves split by trucks rumbling down U.S. 27. It is also the home to Sebring International Raceway, which annually hosts the internationally famous 12 Hours of Sebring motorsports race.

At times, Garrett disguises the names of some of the people he worked with — “the names have been changed to protect the innocent,” you know — to humorous effect. The sports editor in Sebring, “Herman,” was a convicted murderer, Garrett notes. Some of the sports guys at the Tribune will know who that is and chuckle.

They might also snicker at some of the press box stories. Garrett recounts an outburst from a competing writer in nearby Avon Park, who insisted rather loudly that the Sebring writer was “sitting in my chair” in the raceway press box. Most sportswriters in small towns can sympathize with that story.

Garrett returned to the Tribune in 1997 as a correspondent in the New Tampa area of Tampa and would write “more in the next year than I ever thought humanly possible.”

He brings the reader into the locker room during his time covering secondary angles at Bucs games. Believe me, an NFL locker room may sound glamorous but it is not. The smell from those locker rooms will never leave your nostrils.

Garrett covered baseball, college football, NCAA tournament basketball, the Arena Football League and hockey along with his high school coverage. His clip file “grew fatter and fatter.”

But one stands out — June 2, 1998, the day one of his stories landed on the front page (1A) of the Tribune.

An intoxicating feeling.

Garrett joined the Tribune's sports copy desk in 1999 and tells stories about the characters who would call the newspaper. I was delighted that he included the one German soccer fan who would call and ask for the weekly Bundesliga scores. “How did Schalke do?” he’d ask, and we’d dutifully give him the scores and wait for his commentary. Some of the copy editors would even employ slight German accents, to everyone else’s amusement.

Not politically correct, of course, but it eased the deadline tension that soon would be approaching.

Garrett’s memory was a bit faulty at times, particularly about Ford’s funeral. He notes that it was held outside a non-denominational church, but it was actually held in the courtyard at The Lakeside Inn complex in Mount Dora. The rest of his recollections for that sad day were correct; I recall that at the end, a bunch of balloons were released skyward as the loudspeaker blared Norman Greenbaum’s 1969 hit, Spirit in the Sky.

Many journalists will tell you that the business is all-consuming and can kill marriages. It has happened to many of us, and Garrett was no exception. However, he found peace in his second marriage and has two sons. He can look back with pride on a career that allowed him to hone his skills as a writer and editor, and also as a person.

Now a software trainer in the Atlanta area, Garrett continues to battle ALS, and his progression “is slower than typical.” He is unable to use his arms and legs and uses a power chair to get around. But his mind is still sharp. Stringer is evidence of that.

“When you have no way to express yourself physically, you tend to bury yourself in your mind,” Garrett notes. “Reflection is an everyday thing.

“I found direction, purpose, and my voice, and I had some of the best times of my life doing it.”

Stringer is an interesting read, a nostalgic look at a tough business and a fun look at a satisfying career.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed