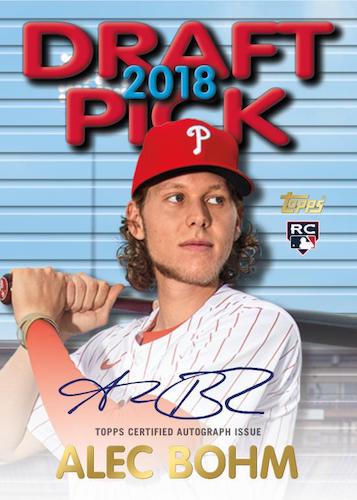

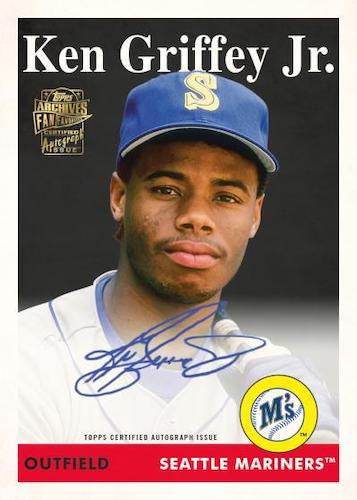

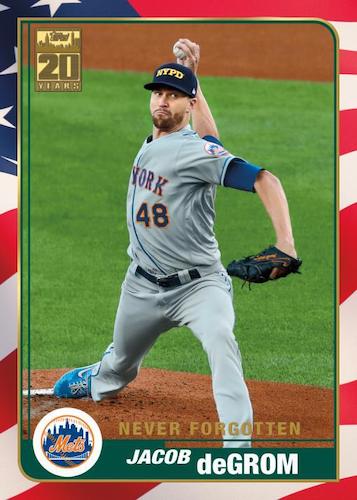

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2021-archives-set-pays-tribute-to-seven-decades-of-topps-card-designs/

|

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2021 Topps Archives baseball set, which will be released in late October: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2021-archives-set-pays-tribute-to-seven-decades-of-topps-card-designs/

0 Comments

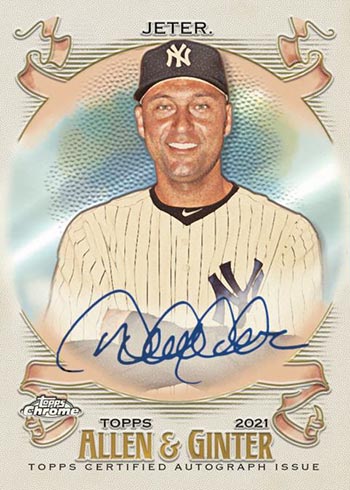

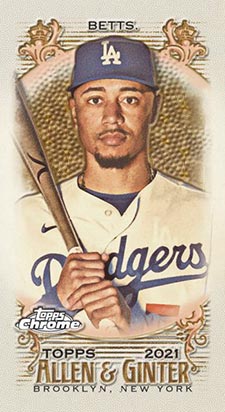

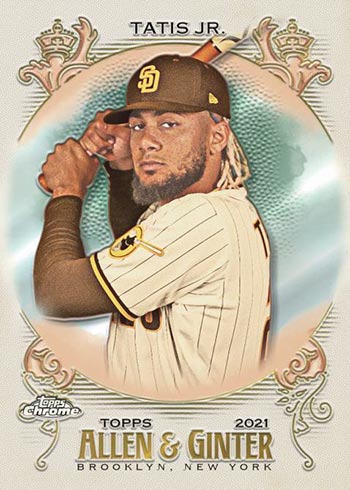

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2021 Allen & Ginter chrome set, which is scheduled to be released in mid-November:

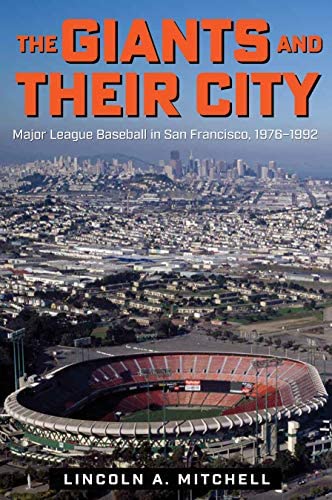

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2021-allen-ginter-chrome-will-unfurl-sophomore-set-in-november/ Here's a review I wrote for Sport In American History about "The Giants and Their City," by Lincoln Mitchell:

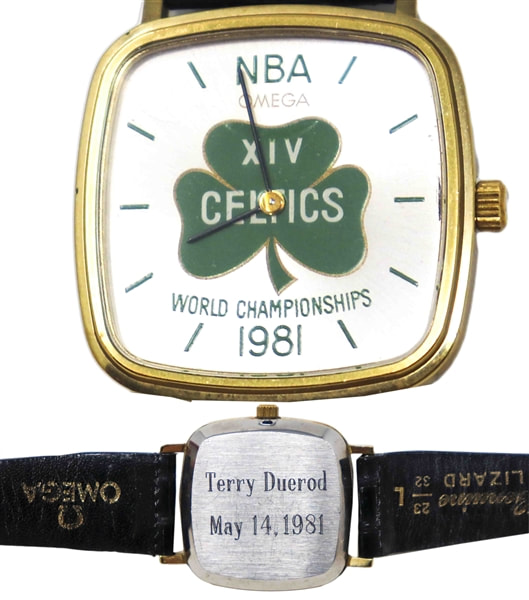

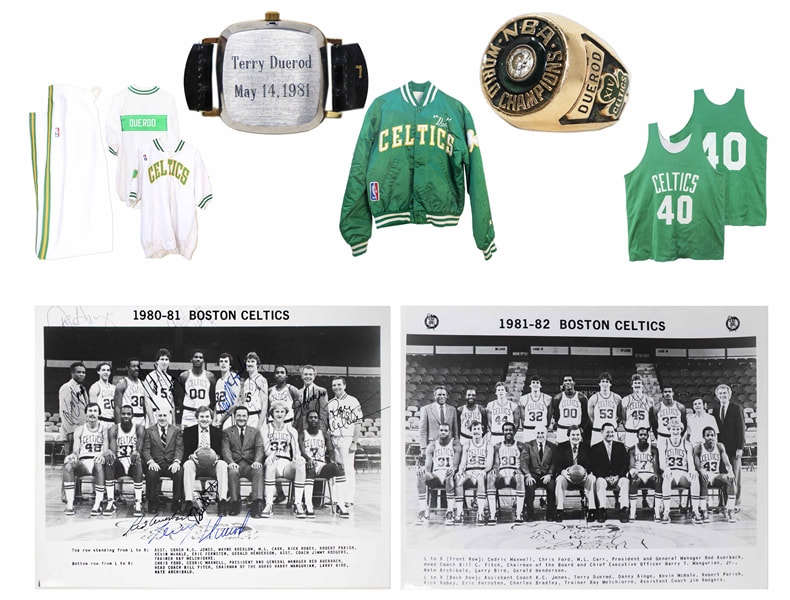

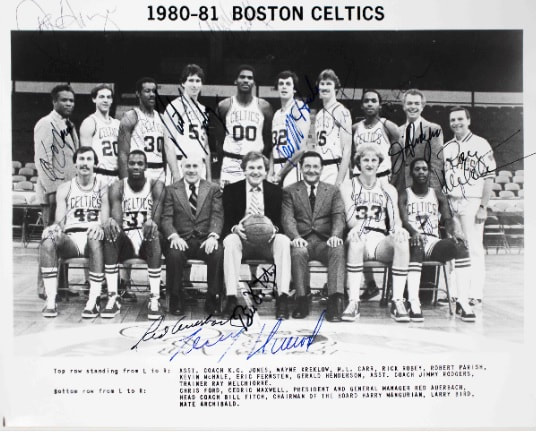

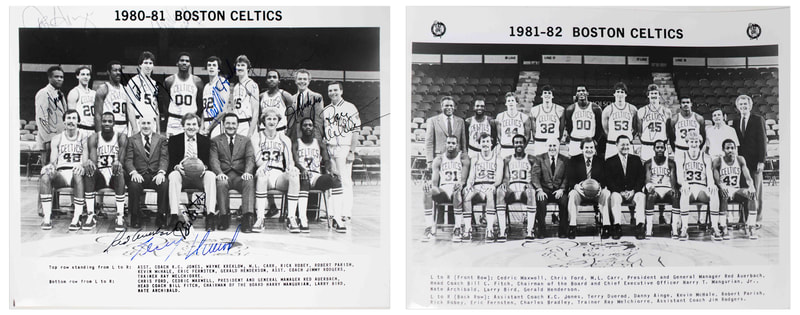

ussporthistory.com/2021/03/27/review-of-the-giants-and-their-city/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about some of the memorabilia of the late Terry Duerod, which is heading to auction later this week:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/terry-duerod-celtics-1981-championship-ring-auction/

I love history. And I especially love baseball history.

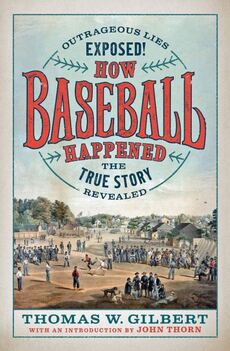

As a guy who got a master’s degree in history — and, who as a kid in the early 1970s, used to tote The Baseball Encyclopedia around on family vacations so I had something to read in the car — there are some things I want from a book about baseball history. First, teach me something new. Second, entertain me. The second part sounds funny, but I mean entertain in the sense that the writer is engaging and not dry. Winded, textbook descriptions about history — baseball or otherwise — is a turnoff. After all, baseball books can be part of a thesis or dissertation, but it does not have to read like one. That is to say, dry and tedious. Brownie points for a sharp wit and/or irreverence. That is especially true in baseball. Certainly, there are books about major events in American history, for example, that should not have the author cracking wise. But this is baseball. So, all that reverence can go out the window, if the author chooses to do so. Thomas W. Gilbert meets both of my criteria in his newest book, How Baseball Happened: Outrageous Lies Exposed! The True Story Revealed (David R. Godine; $27.95; hardback; 383 pages). The book was published last September and won the 2020 Casey Award for best baseball book of the year. Gilbert received his award Monday night.

How Baseball Happened serves as a nice complement to another book about baseball’s early era: John Thorn’s 2012 work, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game.

Thorn wrote the introduction to Gilbert’s book, suggesting that while his own book examined the “what” of baseball, Gilbert addressed how baseball happened while providing the “who” — names of pioneers that many of us have never heard of. Gilbert digs into the beginnings of baseball, debunking the myths that have long been associated with the game. Certainly, baseball experts have gotten past the idea that Abner Doubleday invented the game in a cow pasture near Cooperstown, New York. Gilbert takes it further, noting that neither Alexander Cartwright nor Henry Chadwick can be called the father of baseball. He notes that history can be wrong — sometimes the truth can be forgotten or misunderstood. And sometimes it is erased with lies. “When it comes to telling the story of where it came from, baseball has accomplished all three,” Gilbert writes.

Gilbert, a native of Brooklyn, New York, delves deeply into what was called the “New York game” of baseball — it is the game as we know it now, with some refinements through the years. The New York game was the dominant version played during the Amateur Era, which roughly covers the period before 1871.

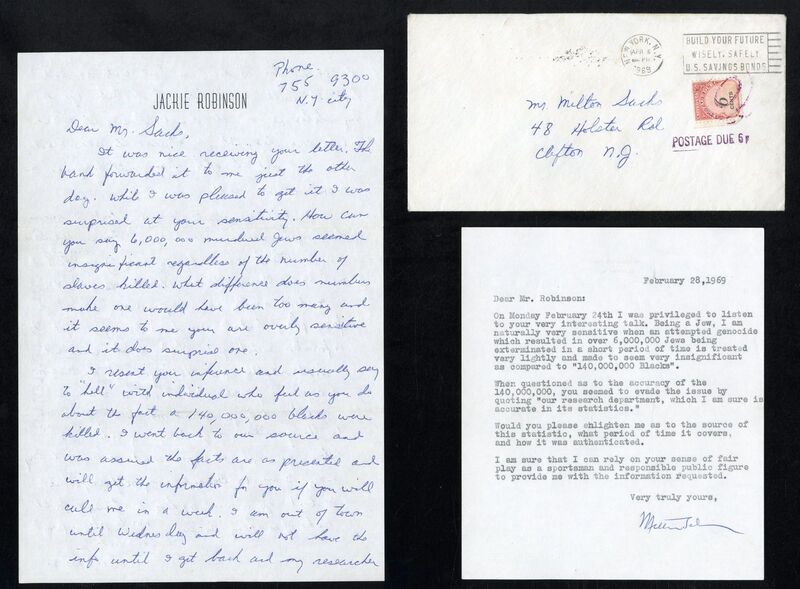

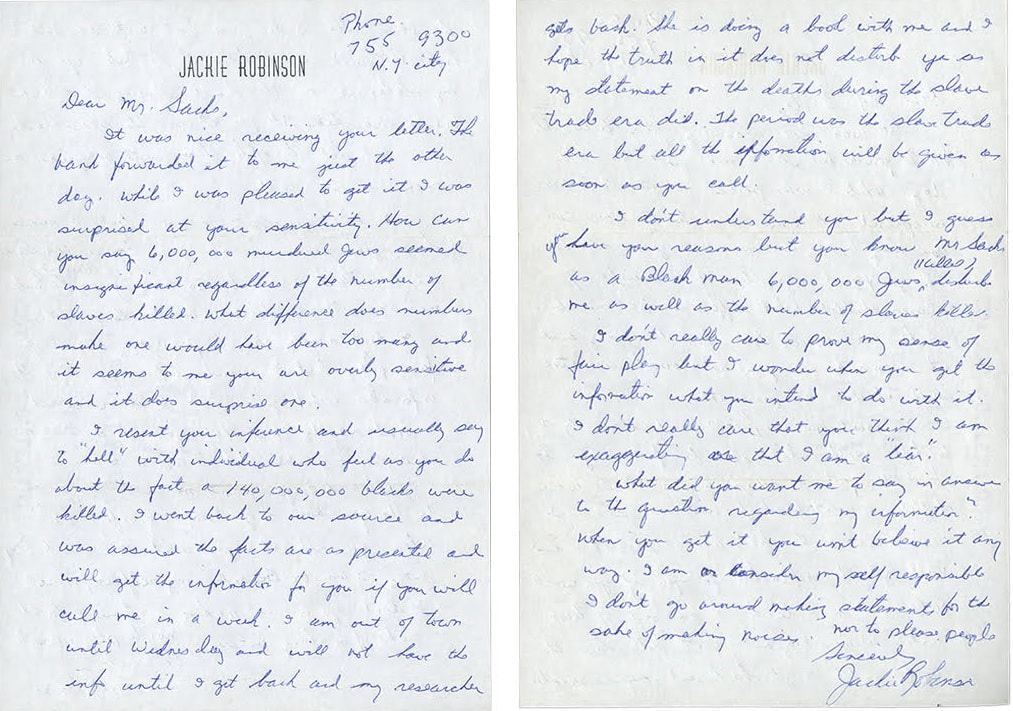

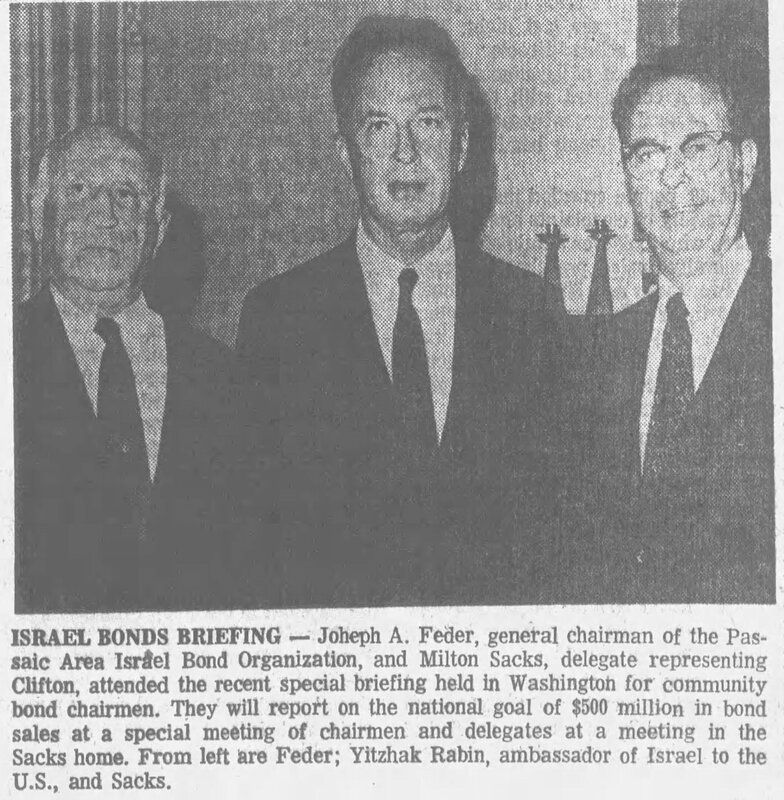

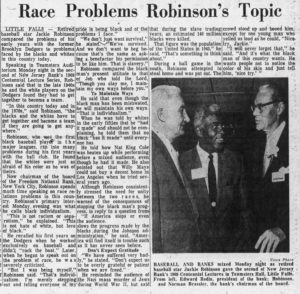

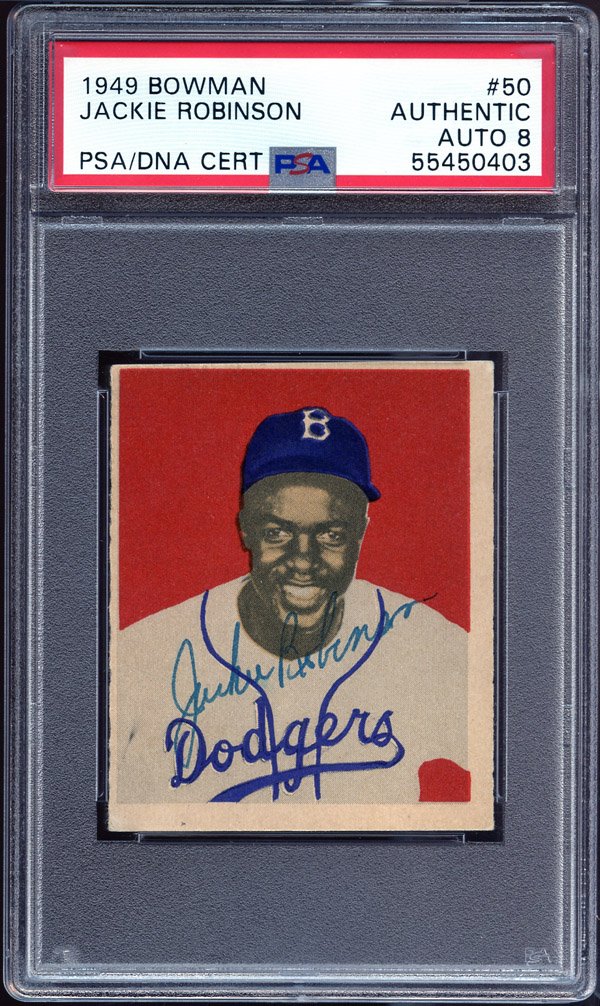

Gilbert also has some great observations. Early in his work, he notes that he does not care much about the history of baseball as a children’s pastime, although baseball history itself is a legitimate topic to research. The game becoming a sport is what caught his eye. “If that had never happened, then baseball would be hopscotch,” Gilbert writes. Gilbert suggests that the rise of the social middle class during the mid-19th century was crucial to the spread of baseball in the United States. He calls it the “Emerging Urban Bourgeoisie,” or EUB (“my ugly acronym,” he jokes). This was a group of businessmen involved in industries like railroads, mass-market publishing and even the telegraph. While it may seem provincial on Gilbert’s part — he lives in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn — there is merit to his assertion that groups of amateurs in Manhattan and Brooklyn built the game. These amateurs joined the military and volunteer fire companies to form the “holy trinity” of U.S. urban culture before the Civil War. “Where is the real birthplace of baseball,” Gilbert asks. “If you open up five history books, you will find at least four answers to this question.” Cooperstown, Hoboken, New York City and even England are the stock answers. But Gilbert says it was Brooklyn. “Humor me,” he writes. And then Gilbert lays out his case. It’s a compelling one. Gilbert adds that the Knickerbockers of New York, a group of white American Protestants who began playing the game in the 1840s, never claimed to invent the game. Rather, they hedged and called themselves pioneers. The graphics in How Baseball Happened are insightful. On pages 230-231, Gilbert offers a map of “How Baseball Expanded.” Starting from New York, Gilbert provides a timeline showing how before the Civil War, baseball clubs had sprouted as far south as New Orleans and as far west as San Francisco. Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, Baltimore, St. Louis, Detroit, Boston and even Hamilton, Ontario, were playing the New York game. That is because businessmen from New York fanned out and traveled to these cities, spreading the gospel of baseball while trying to make a buck. That meant the game was established before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter in 1861. And if you believe in myths, Abner Doubleday was part of the battery that fired the first shots of the Civil War from Fort Sumter. Abner got around, apparently. There is plenty of baseball in this book. For example, Gilbert writes about James Creighton, the first rock star pitcher in baseball history who died at age 21 from “strangulation of the intestine.” “His career was like a nuclear explosion,” Gilbert writes. “It didn’t last long, but afterward the world was never the same.” Creighton’s pitching style led to the formation of the strike zone, and he transformed the pitcher “into the most important defensive position.” He also threw more than 200 pitches a game, and sometimes even 300, which is mind-boggling now. John Creighton, James’ brother, meanwhile, fought during the Civil War and was part of a plot to colonize Nicaragua as a slave state. That did not work, and John eventually became an abolitionist. He later committed suicide. Two very interesting characters in a book of many. But what makes How Baseball Happened so enjoyable is how Gilbert peppers his narrative with brief vignettes. Baseball fans love trivia and history, and Gilbert provides some tasty bites that put the era into proper context. There is the story of Joseph Jones, who advocated physical education for boys and girls and touted the Excelsiors of Brooklyn to promote baseball nationally as a participant sport. Or John Chapman, whose acrobatic barehanded catches earned him the nickname, “Death to Flying Things.” The legendary Green-Wood Cemetery of Brooklyn, Gilbert writes, has “an astounding number” of baseball amateurs from the Amateur Era buried on its leafy grounds. James Creighton is buried there. So are Chadwick, Jones, Chapman, Asa Brainard and dozens of Knickerbockers and other members of Brooklyn teams. “Drawing the Line” recounts the first instance of racial exclusion in baseball. In 1867, the National Association of Base Ball Players passed a rule barring membership to any club “composed of persons of color, or any portion of them.” The outlines of the first color line kin baseball, then, were drawn nearly two decades before Cap Anson and others reached a “gentleman’s agreement” to bar Blacks from the game. “A Glimpse of Stocking” refers not to the Red Stockings or White Stockings teams of the late 19th century. Rather, it references the stockings worn by women and baseball players, which apparently were titillating to the general public. “Showing more lower leg … had erotic impact, judging by photographs of 19th century prostitutes,” Gilbert writes. “Male calves also had appeal.” The San Francisco Chronicle, in an 1869 article, notes that the Red Stockings’ tight red wool stockings that “showed their calves in all their magnitude and rotundity.” A century later, Jim Bouton wrote about baseball socks in Ball Four. “It has become the fashion … to have long, long stirrups, with a lot of white showing,” he wrote. “The higher your stirrups, the cooler you look. Your legs look long and cool instead of dumpy and hot.” Some things never change. Gilbert has a delightful way with words that can alternate between cheeky and snarky. “The Civil War caused about 1.5 million casualties,” he begins seriously before shifting gears. “One of them was cricket.” Gilbert adds that it is unclear why the war affected cricket, “but we do know the reason why we don’t know the reason — the chaos of war.” The NABBP legalized professional baseball for the 1869 season, legitimizing what had been done anyway. That was the year of the Cincinnati Red Stockings and their long undefeated run. The National Association was organized in 1871, with the National League supplanting it in 1876. Baseball as we know it had finally arrived. Gilbert’s research is drawn from 90 books and 25 online databases, Two of those books are his own — 1995’s Baseball and the Color Line, and 2015’s Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research and maintains a blog on Goodreads. How Baseball Began allows fans to view the origins of the game from a fresh angle. Gilbert opens a window into a world of American nativism, when crediting the origins of baseball to British games like cricket and rounders was considered bad form for a country still trying to escape its colonialism from a century before.''' There are new and fascinating characters to read about, and whether or not one believes that baseball as we know it grew in Brooklyn, it is an interesting idea. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an exchange of letters between Jackie Robinson and Milton Sacks, a New Jersey man who questioned Robinson's comparison of Holocaust deaths to fatalities of slaves through the years:

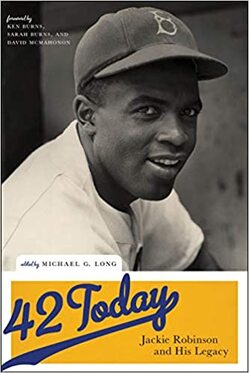

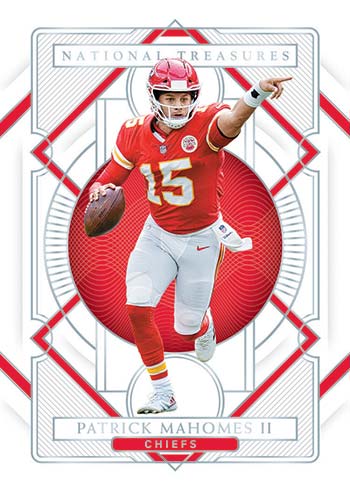

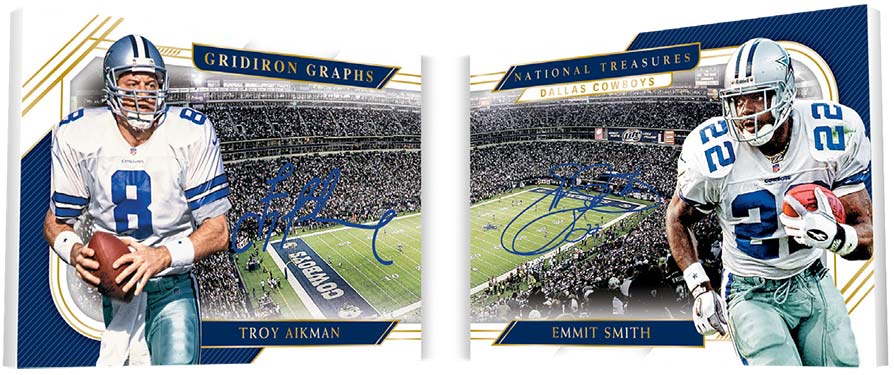

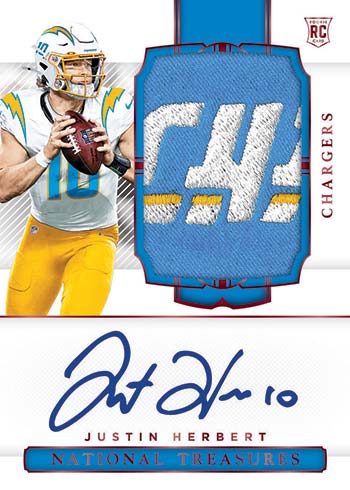

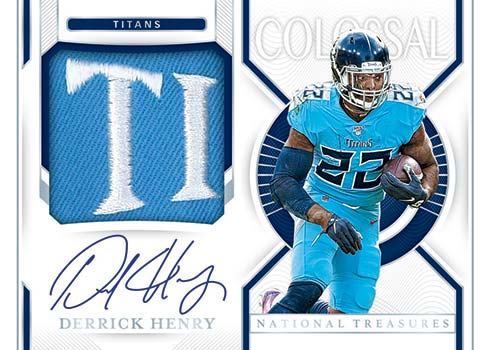

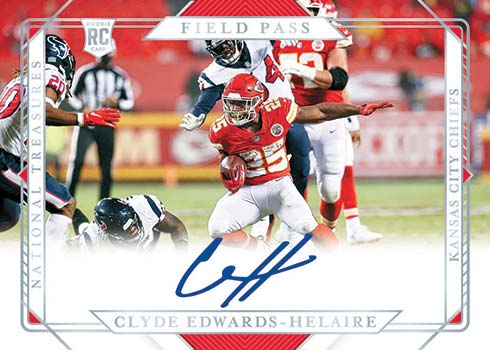

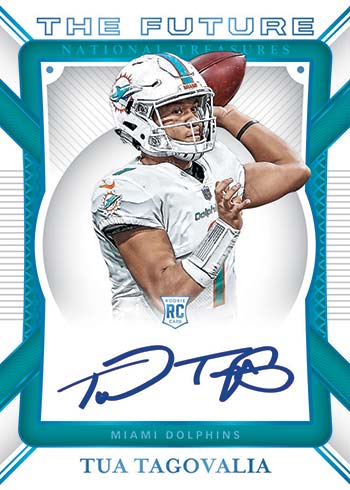

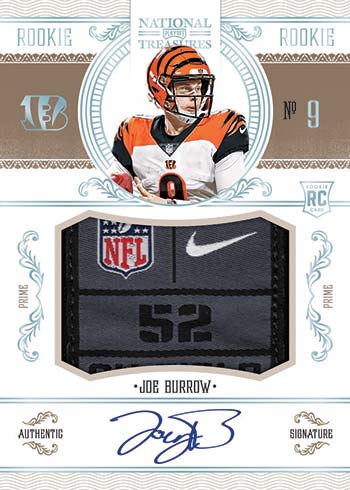

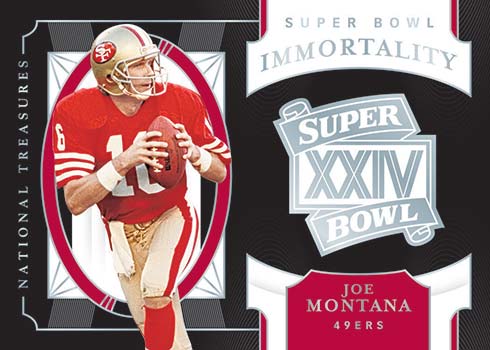

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/handwritten-jackie-robinson-letter-about-race-up-for-auction/  Nearly 50 years after his death, we still don’t really know Jackie Robinson. Oh, we think we do. Sure, Major League Baseball honors him each year on April 15, the day Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. His number, 42, is retired and celebrated by baseball fans. As Jonathan Eig writes in one of the essays in 42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (Washington Mews Books; $27.95; hardback; 239 pages), “We all know the story. We’ve all seen the movie.” Eig is being facetious, of course. There is plenty we do not know — or, in some cases, want to know — about Robinson. A collection of 13 essays, edited by Michael G. Long, provides some necessary context. Long has written about Robinson before, including in his 2008 book, First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson and 2017’s Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography. He has also edited 2013’s Beyond Home Plate: Jackie Robinson on Life After Baseball. In 42 Today, Long also goes beyond home plate, pulling together a collection of authors who cast Robinson in a different light. The essays Long presents are thought-provoking and compelling. Howard Bryant comes out swinging in the first essay, discussing the key difference between advancement and ownership in the context of racial acceptance. Advancement meant that Robinson should be patient, “a credit to his race,” and “accepting of glacial change as progress.” As Bryant points out, advancement was the preferred narrative of whites. “(Blacks) need not sacrifice in the short term provided they agree to a covenant of fairness to be delivered at an unspecified date — as long as it’s not today.” Ownership, Bryant writes, is much different and uncomfortable to some. “It takes the keys to the house of self-determination in real time, without asking, and does not offer points for compromise or patience.” America wanted advancement, but Robinson wanted ownership. Simple as that. Achieving it was not so simple, and even today, that seems to be complicated. Bryant, who has written books about Hank Aaron (The Last Hero), Black athletes (The Heritage) drugs in baseball (Juicing the Game) and injustice (Full Dissidence), provides a powerful start to this book. But as Long writes in the introduction, the essays are presented in such a way that readers can skip chapters or read them out of order and still appreciate the writing. Don’t do that. Read this book straight through. Eig recounts an awkward telephone conversation he had with Robinson’s widow, Rachel, as he contemplated a book about Jackie. Eig, a meticulous researcher whose ability to unearth gems is comparable to Robert Caro’s writings about politics, wanted to get more information about the often-told story of Robinson’s teammate, Pee Wee Reese. The Dodgers’ captain was a Kentucky native who, in the middle of the baseball diamond, put his arm around Robinson in Cincinnati to silence hecklers, a gesture that said, Robinson was not Black, he was a Dodger. Marvelous story. But as Eig interviewed Rachel Robinson, he could sense “frustration in her voice” and received short, curt answers to his questions. Eig finally apologized for wasting Rachel’s time and asked if he did something wrong. “Well yes,” she told Eig. “You assumed that Jack made it because Pee Wee helped. I’m tired of people assuming that he needed the help of a white man to succeed.” Advancement versus ownership again. It hits home. Rachel Robinson went on to debunk the myth — which is unsettling to me because I have a small bronze statue depicting that alleged gesture -- saying that it never happened. Rachel Robinson even attended an unveiling of a similar statue in Brooklyn, but said it never happened. Why attend, Eig wanted to know. “She sighed as if to say it was complicated,” Eig wrote. “I would never understand.” Eig went on to write Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season, in 2007. This book also shows what Robinson meant to the civil rights movement and his political views He endorsed Richard Nixon for president in 1960, and while he certainly agreed with the sentiments of Martin Luther King Jr., Robinson was at odds with how to achieve them. Gerald Early, professor of modern letters at in the African and African American Studies department at Washington University in St. Louis, examines Robinson’s alignment with the GOP in his essay, “The Dilemma of the Black Republic.” Early notes that in 1960, Nixon’s stance on civil rights was stronger than those of his Democratic opponent for president, John F. Kennedy. Early added that Robinson had disagreements with Black radicals (Malcolm X) and Black liberals (Rep. Adam Clayton Powell), and “was at war” with Republican conservatives like Sen. Barry Goldwater. Robinson would face backlash from both extremes, with Malcolm X describing him in a way that made him “a tool of the white power structure” and “a sold-out Uncle Tom.” As Yohuru Williams notes in the essay “I’ve Got to Be Me,” Robinson opposed enforced separatism and enforced segregation. “The first freedom for all people is freedom of choice,” Robinson said. Or, as Peter Dreier noted in his essay, “The First Jock for Justice,” Robinson “viewed himself as much an activist as an athlete.” To the American public, Robinson represented two distinct personalities. Chris Lamb writes in his essay, “The White Media Missed It,” that to Black America, Robinson changed what it was like to be a Black American, a man “willing to sacrifice his life for the cause of racial equality and equal justice.” To white America, Lamb asserts, Robinson was a Black baseball player. Nothing more. Robinson was rarely interviewed by white sportswriters early in his career, and Lamb notes they made no attempt to put his story in historical or sociological context, Lamb writes. Or maybe it was the editors in charge that put the muzzle on those kinds of stories. In The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn wrote about an encounter he had with Eddie Stanky. Kahn, who wrote for the New York Herald Tribune, had filed a story in which Stanky had heard some racial epithets tossed in Robinson’s direction but said, “I heard nothing out of line.” When Kahn filed a story about the exchange, it did not run, with a note from the night sports editor: “Herald Tribune will not be a sounding board for Jackie Robinson. Write baseball, not race relations. Story killed.” That was sometime in 1952 — five years after Robinson broke the color line. For all of his groundbreaking work for civil rights, Robinson “was not a vocal champion” for gender equality. Amira Rose Davis, an assistant professor of history and African American history at Penn State University, has directed two conferences on sports and the LGBTQ experience. Davis notes that through the years, Robinson “displayed a tension” in the belief in traditional gender roles and a more progressive stance on women’s employment and autonomy. Credit Rachel Robinson for changing her husband’s outlook. There are so many different angles to explore in 42 Today. Readers will find themselves challenged to think out of the box, which is a good thing. Progress will never occur without courageous, bold and well-thought-out stances. Kevin Merida, a senior vice president at ESPN and editor-in-chief of The Undefeated, urges readers of 42 Today to remember that Robinson’s struggles were not in vain. Even though Robinson was discouraged with the lack of advancement for Black athletes — and Blacks in general — he had the courage to speak out about what was wrong, no matter how uncomfortable it made his listeners. “Jackie Robinson deserves to be remembered and assessed as the courageous complex man he was,” Merida write in the book’s afterword. “And not as a character from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.” Robinson would probably say today that the goals he aspired to achieve have yet to be realized. History’s wheels can turn slowly, and even 74 years after Robinson stepped on the infield at Ebbets Field, there is still a great deal of work to be done. “Sometimes,” Eig writes, “you can see history right in front of your eyes if you pay attention.” That is the point of 42 Today. The history is there. It’s time to pay attention. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the upcoming 2020 Panini National Treasures football set.

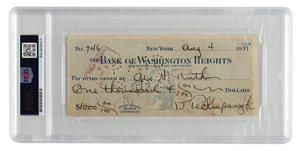

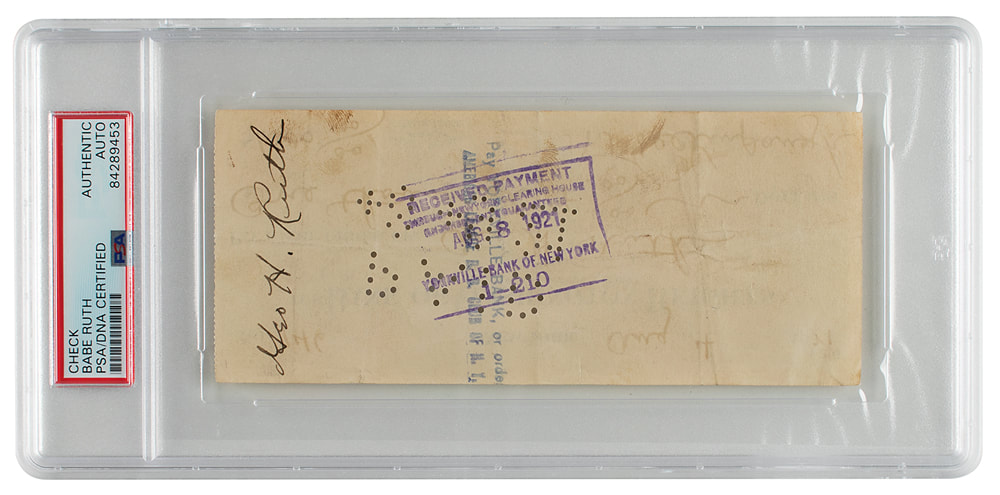

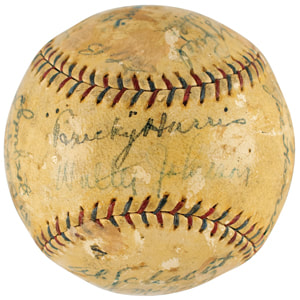

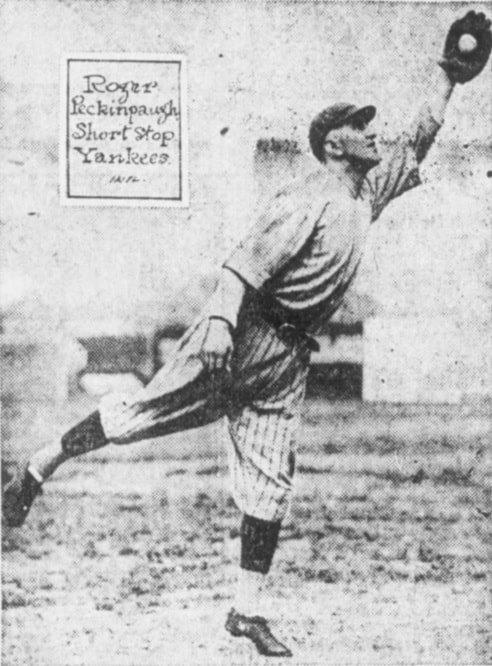

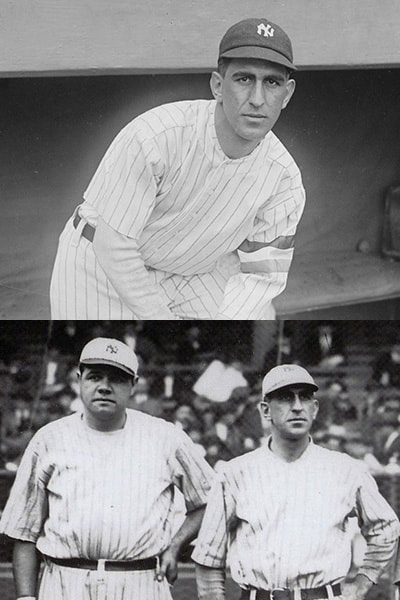

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2020-national-treasures-football-preview/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the memorabilia collection of Roger Peckinpaugh, who played shortstop for the New York Yankees and Washington Senators during the 1910s and 1920s. His grandchildren are selling 10 of his items:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/rr-auction-selling-roger-peckinpaugh-memorabilia-including-check-made-out-to-babe-ruth/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about an upcoming auction hosted by Mile High Sports Cards:

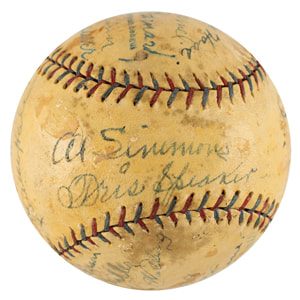

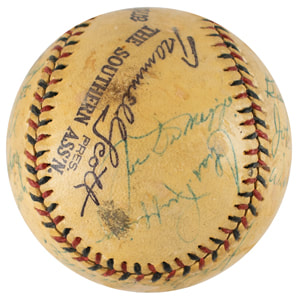

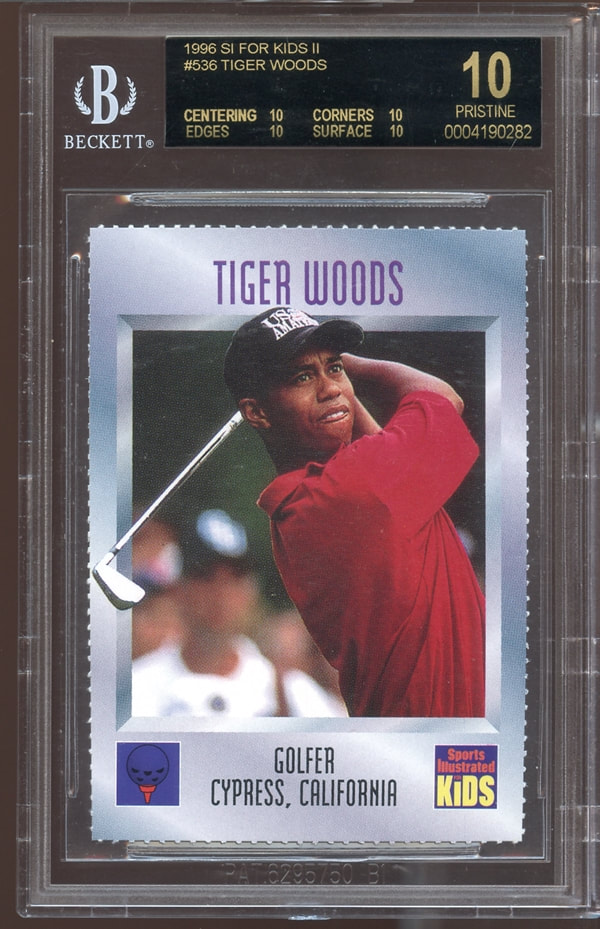

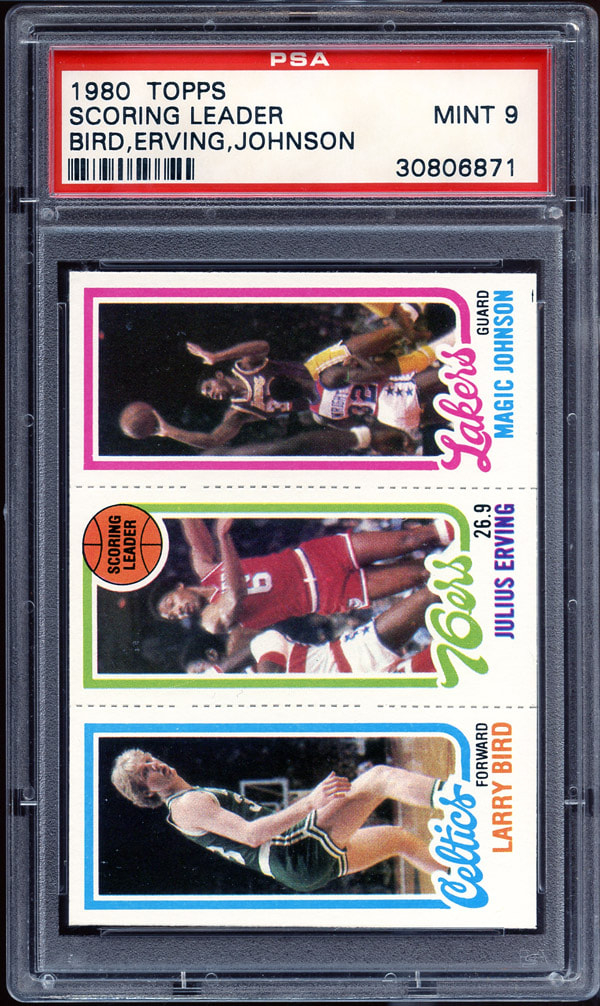

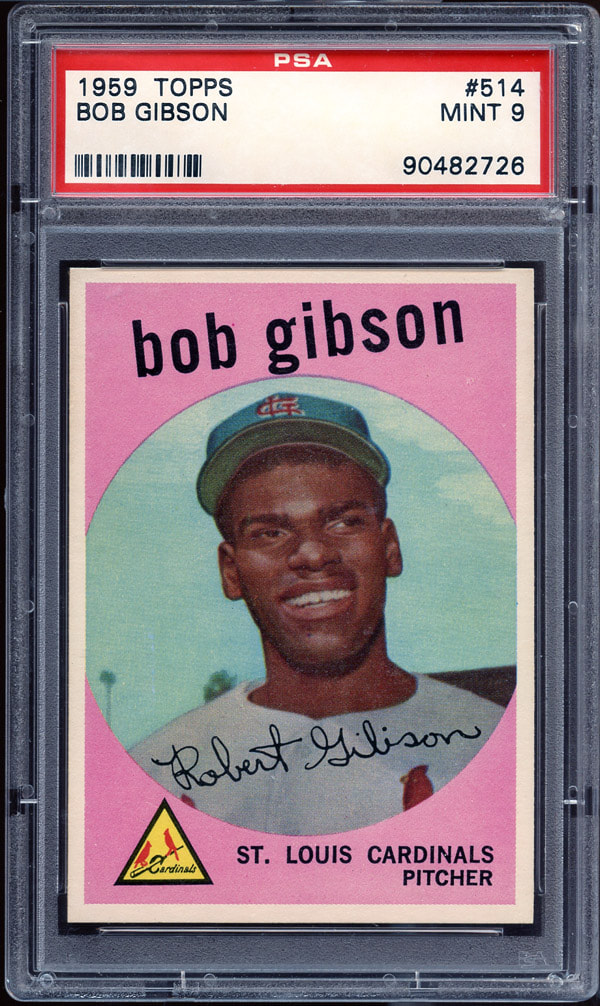

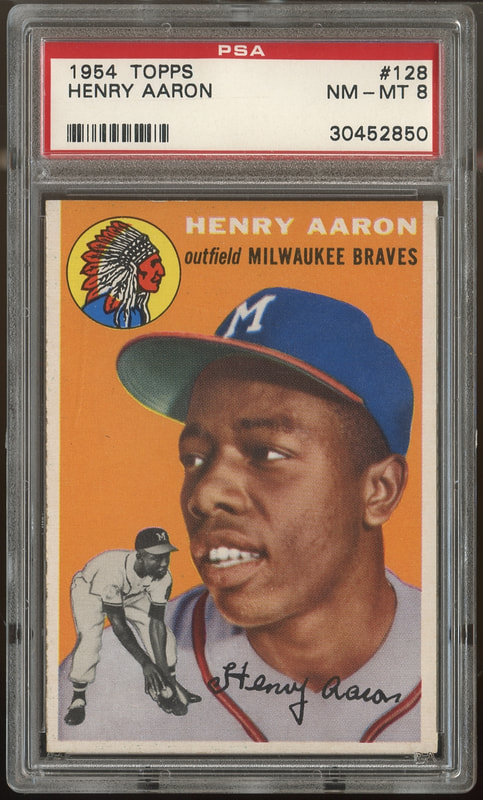

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/mile-high-march-auction-to-include-past-present-icons/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily previewing 2021 Bowman Chrome baseball:

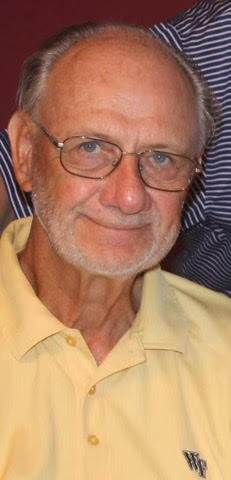

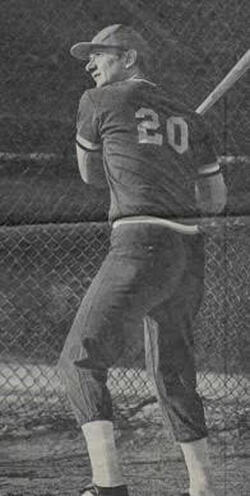

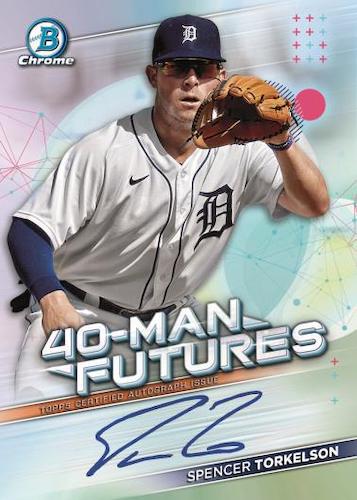

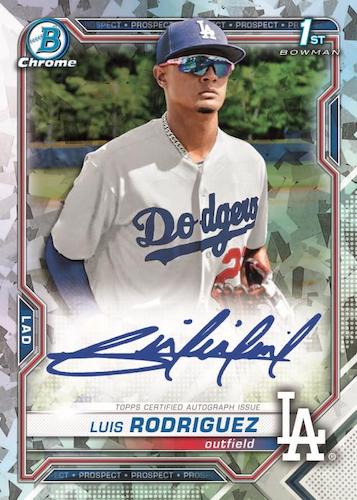

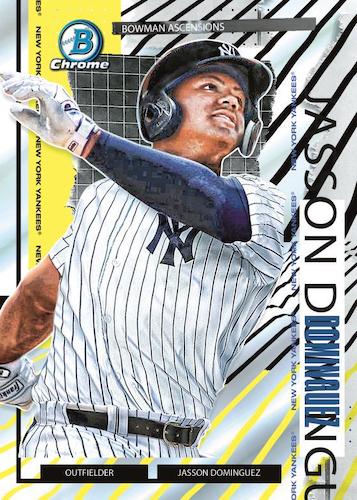

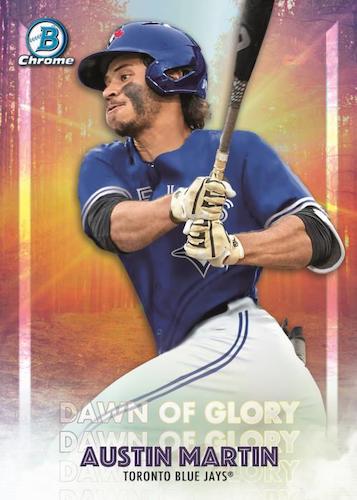

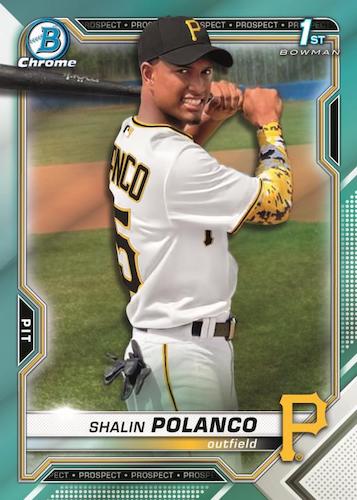

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2021-bowman-chrome-baseball-will-have-3-configurations/  Don Roth would have been horrified to learn that his pitching style was once compared to a Yankees star — a Damn Yankees (or DY) guy, for cryin' out loud. But there it was, in a Daily Tar Heel article in 1961. Don, who competed for Wake Forest University’s baseball team, was described as “a lanky right-handed junkball pitcher — a la Ed Lopat." But Ol’ No-Hit, as he was affectionately called, was a star for all of us. Don lost his battle to cancer on Sunday afternoon. He was 80. For his many friends in the card collecting hobby, this is a devastating loss. Don was a baseball fan to the core, starting with the Brooklyn Dodgers (he cried when Bobby Thomson hit “The Shot Heard ’Round the World” in the 1951 National League playoffs) and then the New York Mets. Baseball was in his blood. He loved to collect baseball cards and immersed himself in the game, as a player, coach and fan. We met through an internet card collecting group, Old Card Traders, more than 20 years ago. We could not have been more different. Don stood 6-foot-4 and I was 5-foot-9. He was still lanky, and while not at 185 pounds like his playing days at Wake Forest, he was still trim for his age. I am not (and never will be) lanky, and probably never 185 pounds again. He was an ACC guy, and I attended the University of Florida, deep in the heart of the SEC. He was from Lynbrook. I was from Brooklyn. And of course, he was a Mets fan and I rooted for the Yankees.  Don at bat during his college days at Wake Forest University. Don at bat during his college days at Wake Forest University. But we clicked. Every year, Don would come to Florida to play golf and enjoy spring training. That became a spring ritual. We never watched a game together, but Don and I would meet for breakfast or lunch. The first time, we met at a Hooters in Brandon, just east of Tampa. Don got the waitress to snap a photo of the two of us. That enabled me to play my best trick on Don. He’d been giving me grief for being a “DY fan,” so I photoshopped a Yankees logo on his golf shirt and posted the picture on my baseball card website. And there it sat for several months, until Don decided to check my wantlist to send cards. And oh, boy, there was quite a post to the OCT message board after that discovery. Fortunately, Don could dish it out and take it, too. We met the following year at a Village Inn, also in Brandon. No photo tricks this time.  Don as a class officer at Lynbrook High School, Class of 1958. Don as a class officer at Lynbrook High School, Class of 1958. With one exception after that, we’d meet at an International House of Pancakes restaurant in Lake Wales. The restaurant was basically halfway between Tampa and Jupiter, where Don stayed during spring training. He watch games and sharpen his golf game, but we made it a point to meet. We’d have a meal, swap stories, trade stuff. I’d usually bring books for Don, and he would have programs and extra business cards. He enjoyed going to minor league ballparks and asking the general managers to autograph their business cards. Quirky, but they loved it. He would also tell stories about his teammate at Wake Forest, Pat Williams, who went on to become a successful executive with the NBA’s Orlando Magic. Another good friend was Ernie Accorsi, who was general manager of the NFL’s Browns, Colts and Giants. In 2016 we were going to meet at the IHOP with fellow trader John Miller, but our wires crossed. Don and I had our usual lunch, but John missed it. A few days later John texted me from the IHOP and asked, “where are you guys?” Oops. In 2017, John could not make it, but he called the IHOP and told the server he was going to pay for our breakfast. Naturally, we thought it was a gag, but John came through. That was the last time we had lunch. Don's cancer treatments began to ramp up, restricting his travel and golf game.  Ol’ No-Hit wasn’t just a nickname, by the way. Before his comparison to Lopat, Don could bring the heat. As a high school senior in Lynbrook (Class of 1958), Don tossed one no-hitter and had five one-hitters. He could recite his stats, like most former players, of course: 105 strikeouts and just six walks. At Wake Forest, Don hurt his arm between seasons and had to mix up his fastball with the breaking stuff. In 1962, his senior year, he went 4-3 during the regular season with a 3.22 ERA, walking only 13 batters in 69 1/3 innings. The Deacons were one victory away from reaching the College World Series, but on a rainy afternoon in Gastonia, North Carolina, Don lost a 3-2 heartbreaker to Florida State University despite pitching 10 2/3 innings and striking out eight batters. Don and was only an infant when he made his public records debut in the 1940 census. He was born March 7, 1940, the son of Henry Roth and Dorothea Knoop Roth, who were living at 15 Russell St. in Lynbrook, New York. Henry worked in Manhattan as an accountant for the Union Pacific railroad company. After college, Don served in the Army. He later became a longtime teacher at his alma mater, Lynbrook High School, and coached the Owls’ baseball and riflery teams. He was the driver’s education teacher at the Long Island school.  Through the years, Don and I would send items back and forth. Cards and books from me, while Don would send cards, newspaper clippings (mostly from Newsday) and emails rating the books he was reading. His kindness extended beyond baseball. In November 2005, he asked his nephew, Bob Roth (another card trading friend), to give my family a tour of the MTV studios in Times Square when we visited New York. Bob worked for MTV’s parent company, Viacom, and set everything up. The kids had a blast. So did their parents. Great experience. It seems as if Don knew everybody. In 2006 I won a Topps contest and secured two tickets to a game at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Had a great time with my oldest son and wrote about the experience. Don wrote back and asked, “Why didn’t you tell me? I know the groundskeeper there; he could have given you a tour.” I should have known.  Don as a driver's ed teacher and coach at Lynbrook High School in 1987. Don as a driver's ed teacher and coach at Lynbrook High School in 1987. In March 2020, Don wrote to tell me his cancer had returned, and he had to undergo an eight-hour IV session. He was reading a book about Ty Cobb to pass the time and just passed off the treatment as “just another drug adventure.” “Stay well and wash your hands,” he advised. Of course, we know that cancer plays no favorites and allows no mulligans. Don knew it, too. He began sending me Yankees cards and memorabilia, noting they were from a friend who had passed away. The friend’s wife did not know what to do with the cards, so Don was giving them new homes. I half believed the story. Given his medical condition, I guessed Don was just clearing out space and getting his own affairs in order. I’ll never know for sure. One of the last of his many charitable gestures was to buy me a Bradford Exchange bronze statue of Derek Jeter. Typically, he could not bear to send me a DY gift through the mail (or get on the Bradford Exchange mailing list and become deluged with offers for Yankees memorabilia), so he had me order it and then sent a check to cover the expense. I drove past that IHOP in Lake Wales a few months ago. It had closed down. That should have told me something. Now, Don can mingle and chat with his favorite Mets: Tom Seaver, Tommie Agee, Gil Hodges, Ed Charles, Donn Clendenon and Tug McGraw. I am sure he will get some business cards signed by Johnny Murphy — and perhaps even by Branch Rickey. And he'll get a pat on the back from Ed Lopat — even if he was a DY. Godspeed, Ol’ No-Hit. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Panini America's 2020 Select Football set:

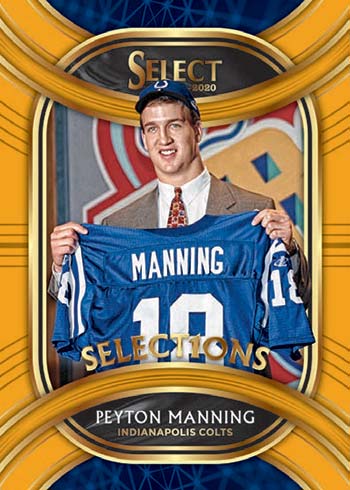

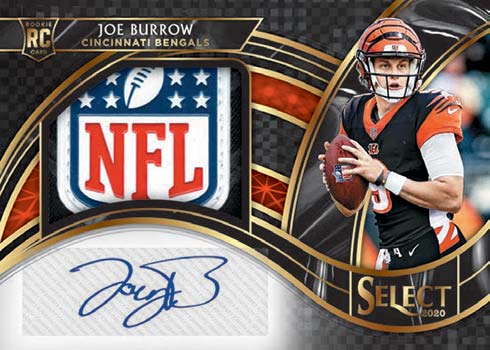

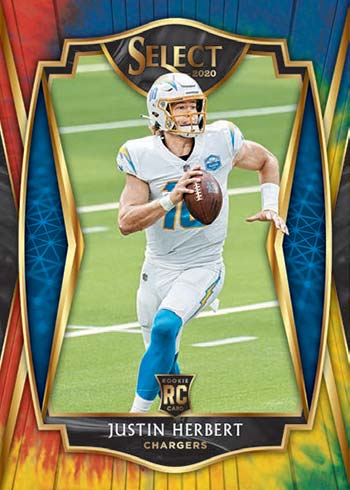

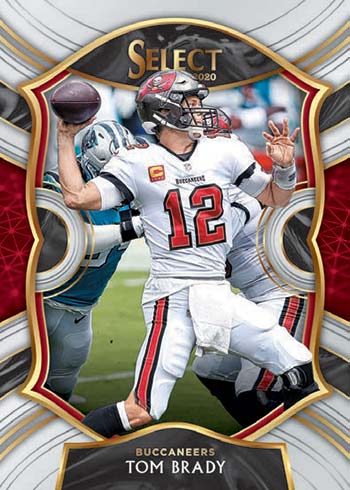

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2020-panini-select-football-offers-variety-plenty-of-parallels/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed