www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/new-orlando-card-show-promoter-aims-for-proceeds-to-help-homeless-hungry-kids/

|

Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Luis "Louie" Morales, the new promoter for the monthly Orlando Area Card Show. Luis is a former NYPD detective and runs a charitable organization to help feed hungry children in Central Florida: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/new-orlando-card-show-promoter-aims-for-proceeds-to-help-homeless-hungry-kids/

0 Comments

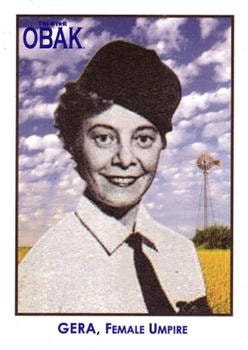

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Bernice Gera, the first woman umpire in professional baseball:

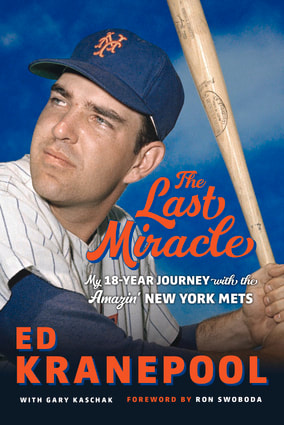

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/obak-card-recalls-anniversary-of-bernice-geras-historic-umpiring-debut/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about former New York Mets first baseman Ed Kranepool, who is having a private sale at his home this summer to sell some of his memorabilia. The money will help pay Kranepool's medical bills, which he incurred while receiving a kidney transplant in May.

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/former-mets-star-ed-kranepool-selling-memorabilia-to-help-pay-off-medical-bills/

Even before it was officially called Wrigley Field, the Chicago Cubs’ ballpark at Clark and Addison streets had its own mystique.

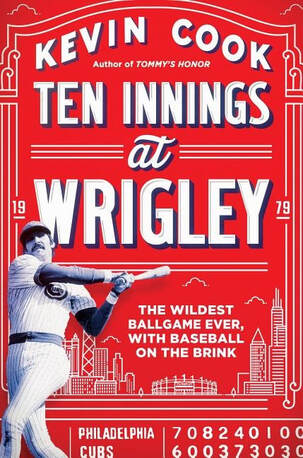

“In All the World No Park Like This,” an advertisement in the April 19, 1923, edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune blared. Or, as Chicago Tribune columnist Daniel Israel noted a half century later, “If baseball is the moral equivalent of war, then Wrigley Field is the moral equivalent of Belgium.” Either description suited the “Friendly Confines,” which could be pure hell for pitchers. No lead ever seemed safe at Wrigley, especially when the wind was blowing toward the ivy covered outfield walls. A Thursday afternoon game at Wrigley 40 years ago fit both descriptions. The Philadelphia Phillies’ 23-22 victory in 10 innings on May 17, 1979, included 50 hits, 11 home runs and 22 total extra-base hits. Kevin Cook brings that craziness to life in Ten Innings at Wrigley: The Wildest Baseball Game Ever, With Baseball on the Brink (Henry Holt and Company; hardback; $28; 253 pages). Cook gives the reader a “you are there” feel thanks to his research, which included watching the Cubs’ telecast and listening to the Phillies’ radio broadcast. Cook, a former senior editor at Sports Illustrated whose earlier works include Tommy’s Honor (2007), The Last Headbangers (2012) Electric October (2017), combines his flair for storytelling with vignettes about the players and fascinating facts about that game at windy Wrigley Field. I enjoyed the tidbits. For example, Randy Lerch and Bob Boone became the first pitcher/catcher duo to homer before taking the field, as both connected during the Phillies’ seven-run outburst in the top of the first inning. Or, pitcher Bill Caudill would become the first client for super-agent Scott Boras. And for people who love numbers, Ron Reed and Dave Kingman marked the first time in the 1979 season in which the pitcher and batter totaled 13 feet tall. Things were odd outside the ballpark, too. Cook writes about a sanitation truck chugging down Waveland Avenue suddenly bursting into flames during the bottom of the second inning. The Phillies had high expectations heading into 1979, coming off three straight National League East division titles. Philadelphia had veterans like Mike Schmidt, Steve Carlton, Pete Rose and Larry Bowa, along with Bob Boone and Tug McGraw. The Cubs, on the other hand, were going nowhere fast, which was not surprising. Their two top hitters, Kingman and Bill Buckner, could not stand one another. No wonder manager Herman Franks “invented grumpiness,” which is a stretch. Franks cut his teeth in baseball under the managerial eye of Leo Durocher, who was much more combative and demonstrative. Still, it’s not a bad description. Cook tells the story of Cubs starter Dennis Lamp, who only got one out in the first inning and lasted 10 minutes on the mound. Lamp’s wife, Janet, arrived late to the game and asked about her husband: “Where is he? How’s he doing?” “Nobody wanted to tell her,” Cook writes. When Donnie Moore finally got the Phillies out to end the first, Philadelphia shortstop Bowa posed a question to Lerch. “Seven runs. That enough for you?” Bowa he asked. As it turned out, no. While the Phillies took later leads of 15-6 and 21-9, the Cubs did not roll over and play dead. Lifted by a 17 mph win that produced three Kingman home runs and a grand slam by Buckner, Chicago pulled to within 21-19 and then tied the game, 22-22, with three runs in the bottom of the eighth inning. Ashburn was not exaggerating when he told his listeners, “We might see grown men cry on the mound." Schmidt’s second homer of the game, in the top of the 10th inning, ended the scoring and left both teams frazzled. “What a wacko game,” Schmidt would say. Cook divides Ten Innings at Wrigley into three parts. The beginning deals with the history of both teams, while the second part goes into the game itself, with each chapter representing a half inning. A graphic at the top of the page of each new chapter in Part Two is a scoreline with the game’s inning-by-inning breakdown to that point. The final part of the book is an afterward, where Cook writes about legacies of the Phillies, who would win their first World Series in 1980; Kingman’s prickly relationship with the media; Buckner, “a pro in the best sense”; the tragedy of Moore, who was always on the edge but became even more dangerous after allowing a home run to Dave Henderson in Game 5 of the 1986 ALCS, with the Angels sitting one strike away from going to the World Series; the legacy of the Boone family (Cook co-wrote a book with Bret Boone in 2008); and Wrigley Field itself. Cook’s short vignettes about each participant are lively, interesting, and at times downright funny. In describing Cubs center fielder Jerry Martin, Cook notes. Cook interviewed players, sportswriters, fans at the game and Cubs historian Ed Harig. He also immersed himself in the archives at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and his bibliography is well-rounded. Ten Innings at Wrigley is a fun, quick read. In terms of crazy games at Wrigley Field, this 1979 is definitely among the weirdest. Cook does a nice job conveying that to the reader. Here are the highlights of the game, preserved on YouTube. You've got to love some of Cubs' announcer Jack Brickhouse's calls. To say he was flabbergasted at times would be an understatement.

Click to set custom HTML

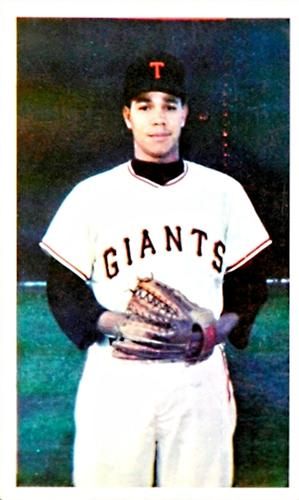

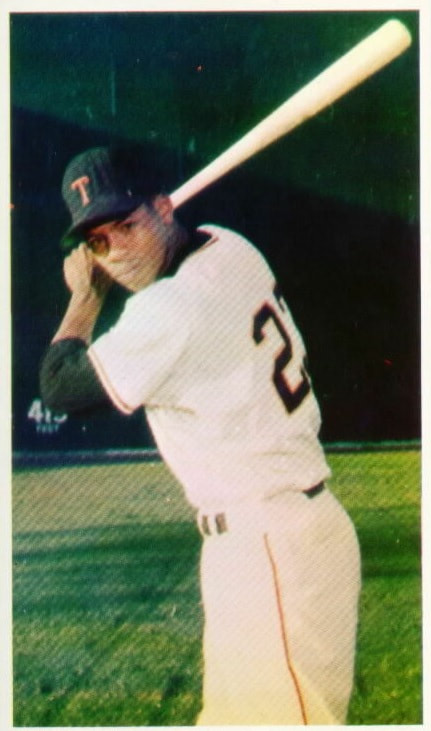

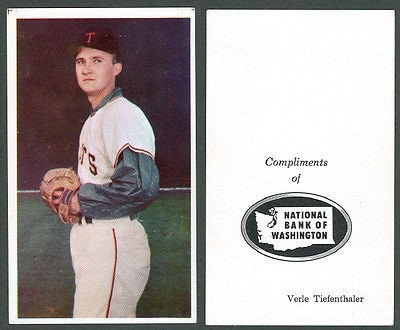

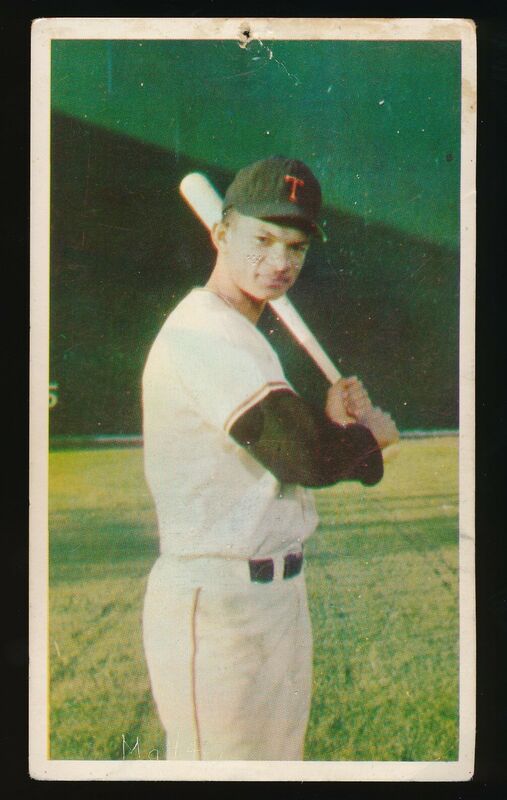

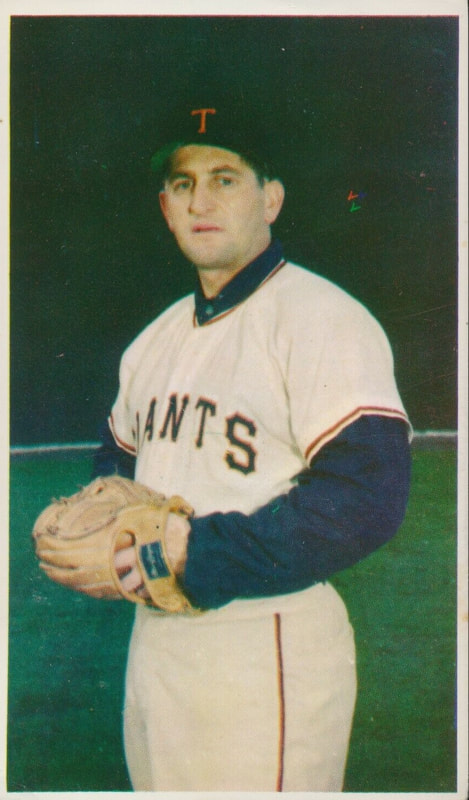

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1960 National Bank of Washington Tacoma Giants, which featured the first baseball card of future Hall of Fame pitcher Juan Marichal:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1960-tacoma-giants-set-featured-hofer-juan-marichals-first-card/ Here's a review I wrote for Sport In American History about legendary Kentucky basketball coach Adolph Rupp:

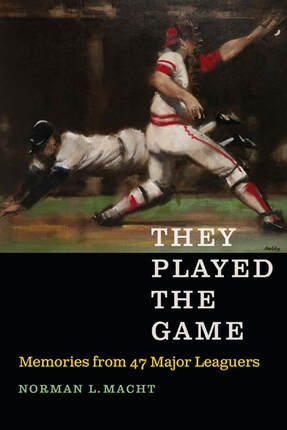

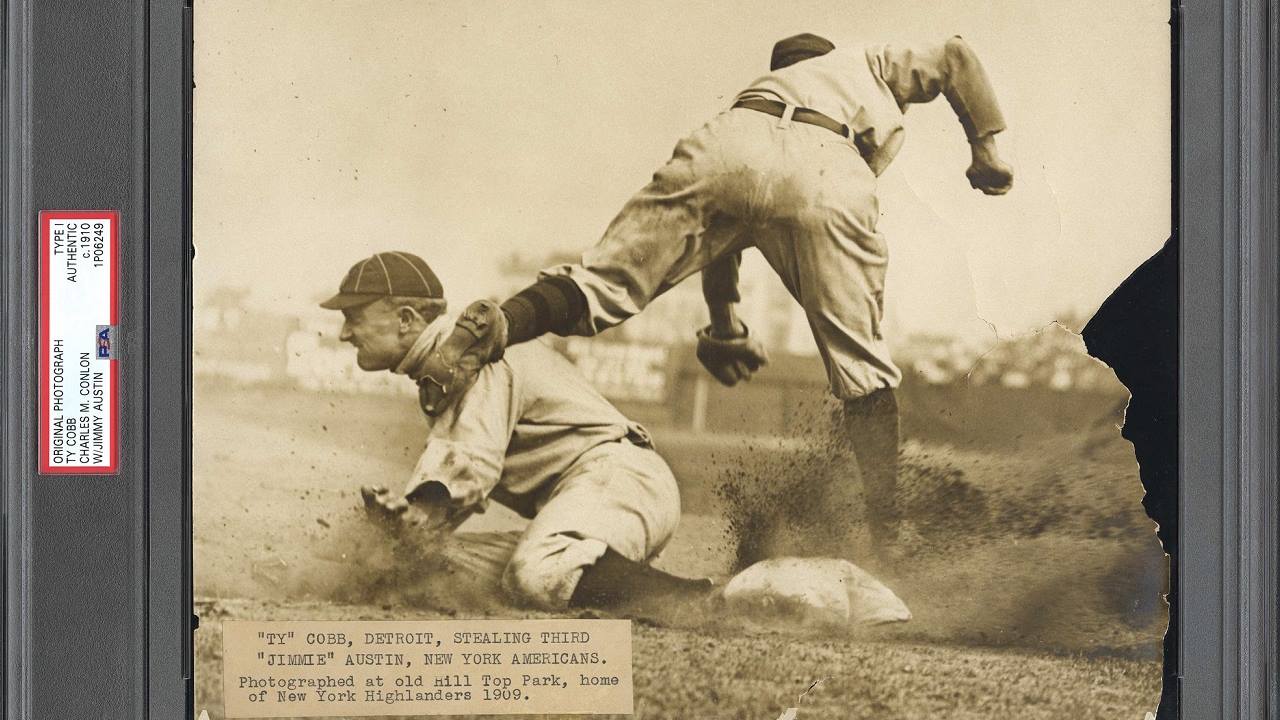

ussporthistory.com/2019/06/15/review-of-adolph-rupp-and-the-rise-of-kentucky-basketball/  “A man’s life is a tapestry,” Norman L. Macht writes. “Not a chart.” The prolific baseball author, who turns 90 in August, weaves a fine collection of player memories in his latest book that rival Lawrence Ritter’s “The Glory of Their Times. In They Played the Game: Memories from 47 Major Leaguers (University of Nebraska; hardback; $29.95, 308 pages), Macht allows 47 players to take a wistful, candid and, in some cases, critical look at their baseball past. Macht’s reliance on primary sources in his previous works is admirable; his interviews with scores of baseball players and executives helped produce his three-volume biography of Connie Mack that was published in 2007, 2012 and 2015. What “began as a 350-page biography” of a legendary baseball manager took 30 years to complete and totaled more than 2,000 pages. But for this compilation, Macht switches gears and allows the players to comb through their memories. “If you wish to do the research to verify or question their facts or versions of events, do so,” Macht writes. “I didn’t.” This type of book works well; baseball is a sport that dwells on its history, and former players can be marvelous storytellers. Macht, who calls himself “an ancient typewriter tapper,” is content to let the players tell the story. Other than a brief introduction, editing for clarity and some questions sprinkled in parts of the text, the book belongs to the players. Macht used the same formula as Ritter: Criss cross the country in search of players and tape his interviews. Like Ritter, Macht transcribed the conversations. Unlike Ritter, who limited his player interviews to men who played during the first 25 years of the 20th century, Macht broadened his base, speaking to former major leagues who played from the deadball era into the 1970s. From Joe Adcock to Don Zimmer, Macht interviews the greats, players who were stars, and players who had the proverbial cup of coffee. He spoke with six Hall of Famers: Richie Ashburn, Travis Jackson, George “High Pockets” Kelly, Ted Lyons, Hal Newhouser and Ted Williams. In a recent podcast with Marty Lurie, Macht said his favorite interview was with former Philadelphia Athletics first baseman Ferris Fain. It’s easy to see why. Fain was an “aggressive, hot-tempered” player who won two American League batting titles and was a five-time All-Star. He also served 18 months in state prison for growing marijuana at his California home during the 1980s for medicinal purposes (his contention) or to sell it (the authorities’ contention). Fain was a competitor who “didn’t so much play the game as attack it,” Dwight Chapin of the San Francisco Examiner wrote in 1986 when Fain received his sentence. Fain, speaking with Macht, punctured the legend of Connie Mack, his manager, questioning his leadership and his ability to run a ballclub. Fain respected Mack, but disagreed with him and used language few players ever did with the Athletics’ manager. In one colorful exchange, Fain told Mack he was not going to throw the ball again after attempting a difficult play; instead, he would stick the ball where the sun didn’t shine, so to speak (Fain’s language was much more colorful). Fain picks up the story: “And (Mack) says, ‘Young man’ — now this was a senile old man that we thought had lost it — ‘Young man, I’d like you to know that that’d probably be the safest place for that ball.’” That “floored the 22 guys in the dugout,” Fain told Macht. “It was the most apropos response I ever heard in my life, even if I was involved.” A fascinating interview. Each interview has something for everyone. The reader discovers how Dave Ferriss got the nickname “Boo,” and how the Red Sox pitcher would watch Ted Williams stand out in left field “taking those imaginary swings.” Ralph “Putsy” Caballero was the youngest third baseman in major league history, making his debut at 16 years, 10 months. He tells Macht about his first home run, straight down the left-field line at the Polo Grounds in 1951. Macht’s introductions to each player interview also spice up the book. In writing about pitcher Carmen Hill, who played from 1915 to 1930, Macht notes that if you made a bar graph of the right-hander’s career, “it would look like a Kansas wheat field with two tall silos side by side in the middle.” Shortstop Mark Koenig tells a story about Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig that is almost Yogi Berra-esque. Koenig, Gehrig and Gene Robertson were sitting on top of the dugout before a game in Waco, Texas. When Robertson noted the fans “can really hurl epithets at you,” Gehrig looked back and answered, “They can’t throw ’em through that screen,” Former catcher John Roseboro spoke about “what you want to accomplish when you call a pitch.” He also expressed his frustration of not being chosen as a manager — Do you want to manage? Macht asked. “Like I need air,” Roseboro said. “As a catcher you are almost managing anyway.” Macht’s interview with Mike Marshall promised to be a good one, and the former reliever did not disappoint. Mike Marshall said when it came to pitching, he listened to Isaac Newton. “He never won a game, but he helped me set some pitching records.” A side note: The Newton reference originally came up in Jim Bouton’s 1970 best-seller, Ball Four. Marshall had been telling players the lower mound in 1969 helped pitchers because it had to do with “the hypotenuse of a right triangle decreasing as either side of the triangle decreases,” Bouton wrote. After Marshall was hit hard in an intrasquad game in March 1969, Bouton wrote that Marshall “just ran into Doubleday’s First Law, which states that if you throw a fastball with insufficient speed, someone will smack it out of the park with a stick.” Marshall’s interview was full of insights — “I’m still persona non grata in major league baseball” he said, referencing his role as a player representative. He had glowing praise for managers Gene Mauch and Walter Alston. He gave Mauch “every credit for the success I had in baseball,” while noting that longtime Dodgers manager Walter Alston, who used Marshall in a record 106 games in relief during the 1974 season, was “a beautiful human being.” “He understood more about people and how to get the most out of them,” Marshall said. Don Kessinger laments the 1969 season, when the Chicago Cubs swooned and allowed the New York Mets to win the National League East. “We had the best talent in baseball, and we didn’t win. I don’t know why,” Kessinger tells Macht. “If we had won in ’69, we probably would have won the next two or three years.” Macht visited John Francis Daley on the former player’s 100th birthday (May 25, 1987), and the former shortstop talked about the phrase he coined — claimed by others, but Daley insisted he said it first — “You can’t hit what you can’t see.” That was Daley’s comment to his manager, George Stovall, after taking a called third strike against Washington Senators pitcher Walter Johnson. There are other great stories and storytellers, too — Bobby Thomson, Harvey Haddix, Woody English and Joe DeMaestri, to name a few. And then there is Ted Williams, who Macht said “spoke in capital letters, sometimes 60-point headlines.” They Played the Game speaks to fans of baseball history in capital letters, too. Macht’s mixture of player interviews works well, and he is planning a second volume, drawn from other taped interviews. I can’t wait. Here's a story I wrote for Cox Media Group about a classic Charles Conlon photograph of Ty Cobb that was sold to a private buyer for $250,000. Crazy.

www.ajc.com/news/national/famous-photo-cobb-sells-for-250k-private-sale/7OQa5Wz0YcAF1WbzhsdoHI/

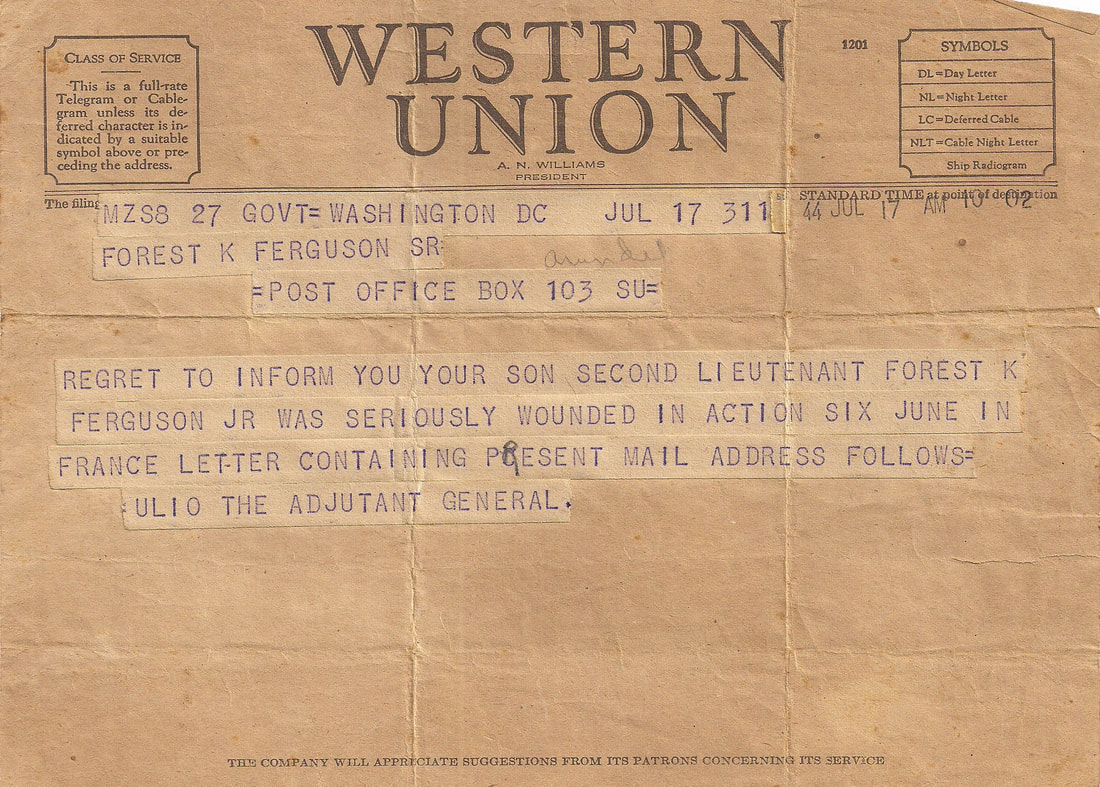

Today is the 75th anniversary of D-Day, the beach landings by the Allies on France’s Normandy coast that turned the tide of World War II.

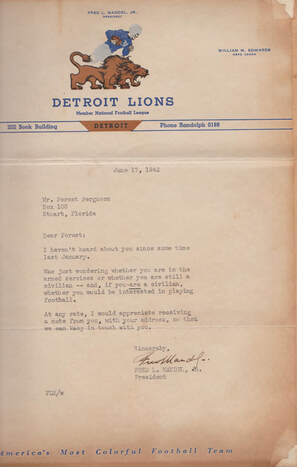

June 6, 1944, was the “longest day,” the largest air and sea invasion in history. More than 150,000 Allied troops, transported by 7,000 boats, landed on the five beaches, code-named Omaha, Utah, Juno, Sword and Gold. More than 9,000 Americans died in the water or on the beaches. Many who survived were never the same again. I put Forest K. Ferguson Jr. in that latter category. “Fergie” was a star multi-sport athlete at the University of Florida and had a promising career ahead of him in professional football if he survived the war. Ferguson survived, but barely. He suffered a serious head wound from shrapnel while ascending a draw at Omaha Beach and died from his wounds 10 years later. What Ferguson did that day on the Normandy coast was heroic and is a tale worth retelling.

But first, some background.

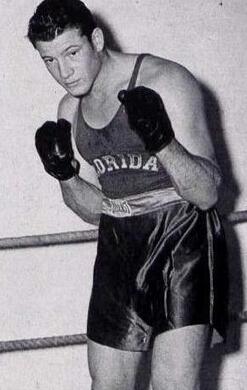

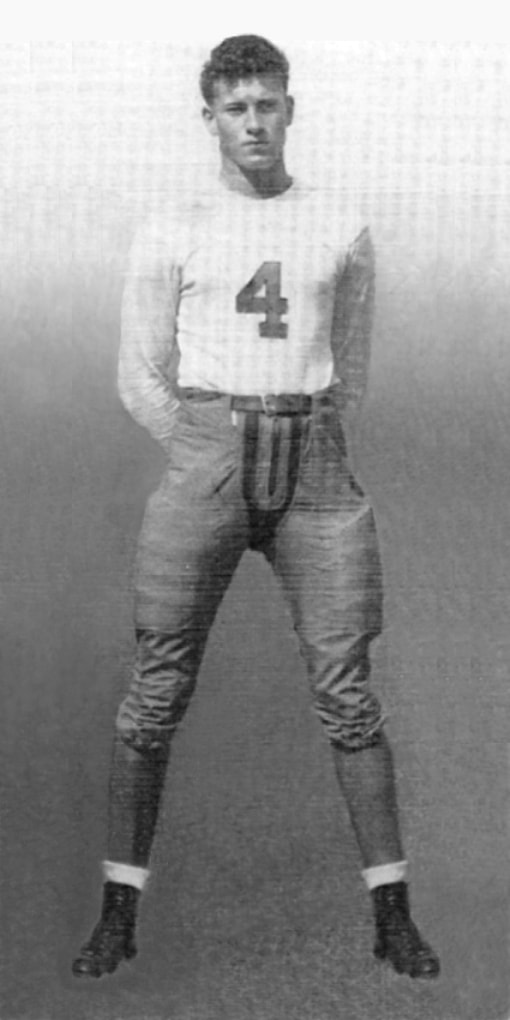

Ferguson was the Pat Tillman of the Greatest Generation, although Fergie was not struck by friendly fire. Residents of Martin County, Florida, where Ferguson grew up and lived, compare him to the hero in the 1998 movie, Saving Private Ryan. Ferguson was a strapping young man who stood 6-foot-3 and weighed 205 pounds. He was 15 days shy of his 25th birthday, a second lieutenant serving with the 29th Infantry Division, 116th Regiment. He cut an imposing figure in uniform and looked like a hero. But make no mistake: Every Allied soldier who landed on the beaches or parachuted behind enemy lines was a hero on D-Day. There will be many speeches made today, with leaders from the Allied countries, including President Donald Trump, in attendance. Heroism and patriotism will be the themes, and deservedly so.

The speakers will recall the valor of the soldiers and the cleverness of the Allies, who signaled the invasion was imminent by sending a coded message to the French underground via a BBC radio broadcast, using three lines from Paul Verlaine’s poem, “Chanson d’automne”:

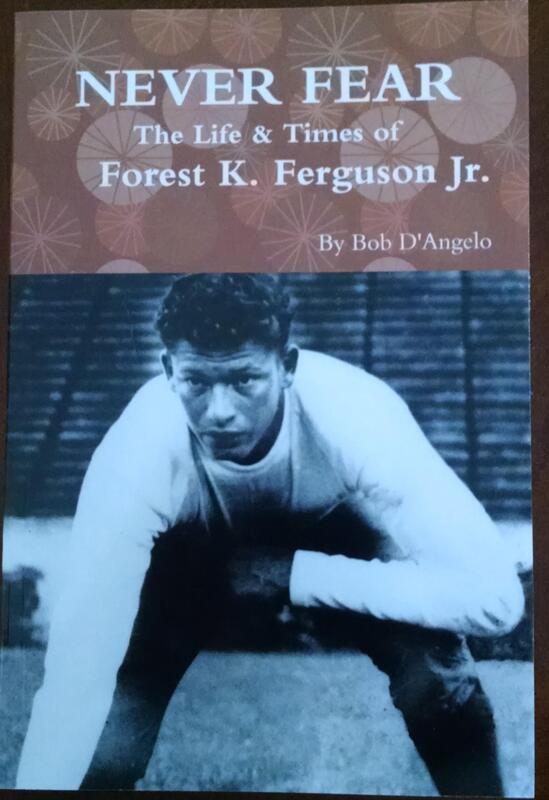

“Blessent mon Coeur/D’une langueur/Monotone.” That translates (loosely) to “My heart is drowned/In the slow sound/Langurous and long.” The solemn D-Day a75th anniversary ceremonies began Wednesday, with a 97-year-old veteran reenacting his parachute jump and U.S Rangers scaling the Normandy cliffs. There are thousands of heroes that day, but I will focus on Ferguson because I knew the man — not personally, since he died in 1954, three years before I was born. However, I researched his life and in 2015 published a book about him, “Never Fear: The Life and Times of Forest K. Ferguson Jr.” I felt like I knew him after combing through records and newspaper clippings. And I am still learning more. Shameless plug: You can buy the book on Amazon or from my Sports Bookie website.  While playing for the Western Army All-Star football team in the fall of 1942, Ferguson and teammates paid a visit to Columbia Studios in Hollywood, where they posed with actress Linda Darnell. While playing for the Western Army All-Star football team in the fall of 1942, Ferguson and teammates paid a visit to Columbia Studios in Hollywood, where they posed with actress Linda Darnell.

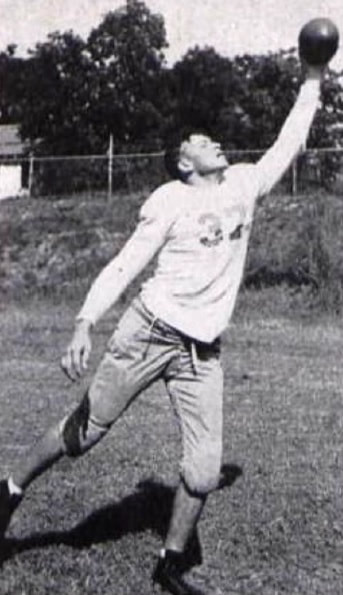

Ferguson led Stuart High School’s football team to a 9-1 record and became the second football All-American in University of Florida history. In the spring of 1942, he threw the javelin 203 feet, 6 ½ inches to win the 1942 AAU national junior outdoor meet in New York, tossing the spear seven feet farther than the runner-up John G. Adair of the Norfolk Naval Training Station.

While in training with the Army, Ferguson played for the Western Army All-Star football team and played in several exhibitions, including one game at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California Ferguson was commissioned as a second lieutenant July 9, 1943 and joined his unit in southern England five months later. While in England he played football for the 29th Division Blues, who went unbeaten between January and March 1944. But the real business was at hand. The Allies were preparing to launch an invasion across the English Channel, and when the troops hit the beach on the overcast morning of June 6, it was chaos. “As our boat touched sand and the ramp went down, I became a visitor to hell,” said Harry Parley, private from the Bronx. “It was chaos,” said medic Marion Gray of Tennessee. “The bowels of hell, and it continued through the day.”

As he moved from the beach toward the draws, or rises, that rose to the cliffs of Omaha Beach, Ferguson noted the maze of barbed wire that crisscrossed the path, making any soldier an easy target for German sharpshooters in the pillboxes atop the bluffs.

Ferguson convinced three men to follow him, and “with complete disregard for his safety,” moved forward under fire with a Bangalore torpedo. The Bangalore was an explosive charge placed within one or more connected tubes. The charge was put at the front and a blasting cap or fuse was closest to the soldier. Fergie crawled forward under intense fire, put the Bangalore under the wires and exploded the weapon, creating a gap for soldiers to pass through. Ferguson and his unit surged forward up the draw, but Fergie was hit in the side of the head by a piece of shrapnel from a high explosive shell. He would be unconscious for nearly two months before awaking in a hospital in England.

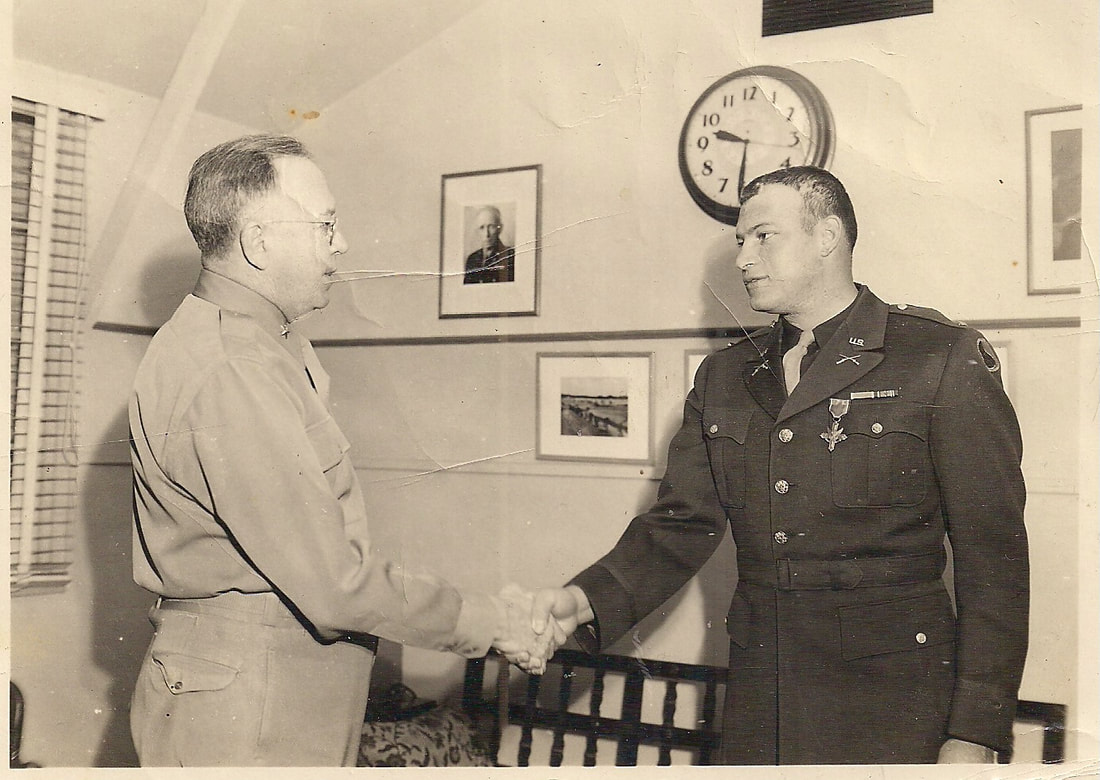

Ferguson would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions on D-Day. His citation read, “The personal bravery, initiative and superior leadership of Second Lieutenant Ferguson exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 29th Infantry and the United States Army.”

He also received a World War II Victory Medal and a Service Lapel Button. There is no record of a Purple Heart, although Ferguson certainly would have qualified. Longtime residents of Stuart believe Fergie should be in line for a Congressional Medal of Honor, which has been awarded to 464 members of the U.S. military — 266 posthumously. Four soldiers received a Medal of Honor for their actions at Normandy, including Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of the 26th president. That seems like a low number, considering the bravery exhibited by so many soldiers.

With a metal plate in his head and his speech affected because of his wartime injuries, Ferguson would never play sports again. He helped coach a semipro football team of veterans and was an assistant at his high school alma mater.

Ferguson died May 15, 1954, a month shy of his 35th birthday. His memory has been kept alive by his university, which awards an annual award in his name to honor the Gators’ most courageous player. In his home county, the three high schools there vie annually for the Fergie Ferguson County Football Championship Trophy. In 2015, the City of Stuart dedicated a bandstand in Ferguson’s name on Memorial Day in the city’s Bandstand Park. As we look back and reflect on D-Day, we should remember the sacrifices made by soldiers such as Forest K. Ferguson Jr. And everyone else. The number of D-Day survivors is dwindling daily, but our gratitude should never wane.

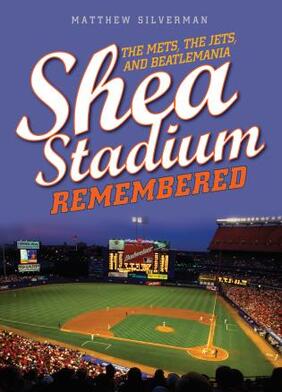

Any baseball fan who attended a game at Shea Stadium had a story to tell.

It rarely had to do with the charm of the place, which was basically sterile. Shea did not generate the nostalgia associated with Ebbets Field in Brooklyn or the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan. But oh, what memories. The Ol’ Perfessor. The Amazin’ Mets. You Gotta Believe. The Fab Four. Broadway Joe. From 1964 until 2008, there were countless memories in Queens. Those moments are what Matthew Silverman pulls together in his tribute to the old ballpark in Flushing Meadows, Shea Stadium Remembered: The Mets, the Jets and Beatlemania (Lyons Press; hardback; $29.95; 232 pages). The book contains 61 chapters and an appendix, and plenty of fun facts and sentimental journeys. Silverman has plenty of Mets-related books under his belt, including Mets Essential: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Fan (2007), 100 Things Mets Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die (2008), Mets by the Numbers (2008), Shea Goodbye, with Keith Hernandez (2009), New York Mets: The Complete Illustrated History (2011) and Best Mets (2012). Silverman certainly knows his stuff when it comes to the Mets, and he is equally knowledgeable about Shea Stadium. He confessed he has nostalgia about the old structure, “which is imagination backwards.” Who can blame him?

So, indulge me for a few paragraphs as I contribute my own nostalgia.

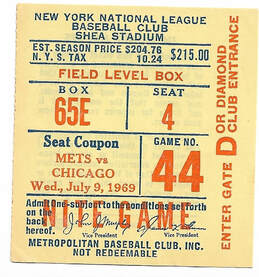

My first trip to Shea Stadium was June 17, 1967, and the Mets (19-37) were hosting the Chicago Cubs (31-26). My father was the Cubmaster for Pack 222 in Brooklyn, and he got the bright idea of taking his Cub Scouts on a field trip to Shea Stadium. My dad was always coming up with field trips — to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, West Point (our bus broke down in the snow just past Yankee Stadium), Coney Island, Consolidated Edison in Manhattan (we had lunch at a Horn and Hardart automat), the Gil Hodges Bowling Lanes in Brooklyn, Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay and the Vanderbilt Museum in Centerport. But Shea Stadium was his most ambitious project, because he, along with maybe five or six chaperones, was taking 30 kids on the subway from Brooklyn to Queens. Miraculously, nobody got lost. We sat in the third deck by the right field foul pole. Miraculously, nobody fell out of the stands. The Mets lost, not so miraculously, 9-1, with Bill Denehy taking the loss. Denehy, who is a footnote for baseball card collectors because he shares a 1967 Topps rookie card with Hall of Famer Tom Seaver, is now blind and living in the Orlando, Florida, area, where in March he said his caretaker allegedly stole more than $17,000 from him. That’s a sad footnote. Silverman’s book, on the other hand, is upbeat. The early Mets were lousy, but they “offered fun.” There was Banner Day, when Mets fans would parade around the stadium with bedsheet banners, and the ultimate sign-maker, Karl Ehrhardt, who told the Journal News of White Plains in 1970 that he had 705 different signs in his inventory. One could say these fans traced their ancestry from the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Sym-Phony Band and the cowbell-clanging Hilda Chester. There was Mr. Met, the team’s mascot, and Mets manager Casey Stengel, who doubled as the team’s cheerleader, talking in circles but promoting the team with every fractured bit of syntax.

The Beatles, who played at Shea Stadium on Aug. 15, 1965, performed 30 minutes of music before 55,600 fans, who began screaming from the first notes of “Twist and Shout” until the final strains of “I’m Down” (does anyone remember John Lennon playing the organ with his elbow near the end of the song?).

Silverman bounces off some good lines in his prose, comparing Mets fans’ attendance at Dodgers and Giants games — the former teams they rooted for — to “going to dinner with your ex at your neighbor’s house.” He gives the reader some fun facts, too. For example, Shea Stadium’s first chief electrician, Lou Beal, estimated the candlepower of Shea Stadium’s lights were 2,341,000 — making the field “bright as day,” even at night. And despite the constant planes flying over Shea into nearby LaGuardia Airport, there was only one fatality — in 1979, during the halftime of a New York Jets-New England Patriots game, when a radio-controlled plane — in the shape of a lawn mower — went out of control and struck two fans. One of the fans, John Bowen, died several days later from his injuries. “Though sad, it is ironic that of the countless thousands of planes of every size and shape that flew over Shea, the lone fatality involved a radio-controlled flying lawnmower,” Silverman writes.

There were so many great memories: Tom Seaver’s near perfect game in July 1969; the miraculous catches by Ron Swoboda and Tommie Agee during the 1969 World Series, and the sight of Cleon Jones taking a knee (reverently) when he caught Davey Johnson’s fly ball to end the ’69 Fall Classic; the Mets rallying from two runs down with two outs in the 10th inning of Game 6 in the 1986 World Series; the return of Willie Mays to New York; and Mike Piazza’s emotionally charged home run when baseball resumed in New York after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

There was the Kid, Mex, Doc and Straw. Jesse Orosco throwing his glove skyward after the final out of the 1986 World Series (did it ever come down?), and the Subway Series returning to New York in 2000 after a 44-year hiatus.

There was Joe Namath throwing for a heavenly 4,007 yards for the Jets in 1967, and evangelist Billy Graham looking toward the heavens as he preached in 1970. The New York Sack Exchange that could cleave an offense, and Tug McGraw, who made you believe. There was a 23-inning loss to the Giants on May 31, 1964, and Jim Bunning’s perfect game three weeks later on Father’s Day, the first National League perfect game since 1880. And, don’t forget Bud Harrelson and Pete Rose rolling in the dirt during the 1973 NLCS.

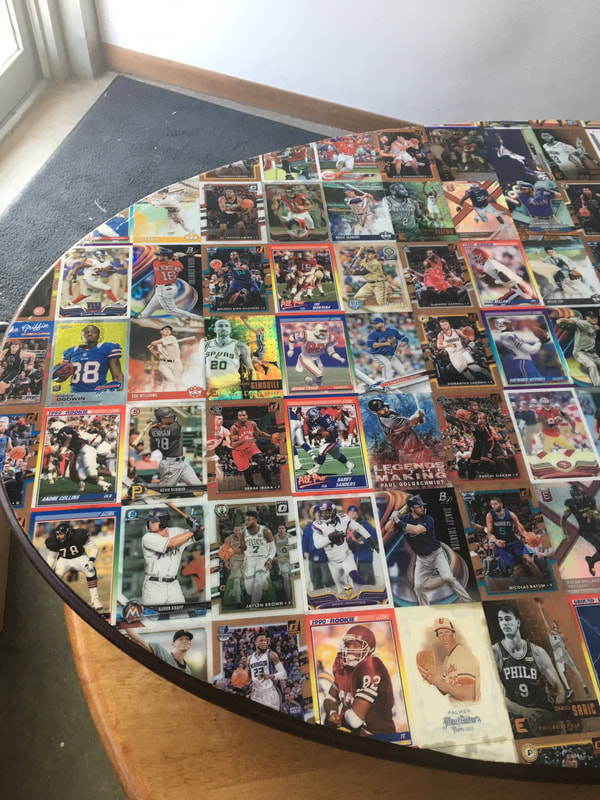

The only real glitches in this book are Silverman’s erroneous labeling of the popes who came to Shea. He writes that Pope John Paul XVI became the first pontiff to visit the United States in 1964 (it was Pope Paul VI) and Pope John II came in 1979 (it was Pope John Paul II). Through good times and bad, Shea Stadium weathered it all. “The Mets at Shea were 44 acts in a very long Greek tragedy,” Silverman writes. Silverman documents all the comedy, tragedy, drama — and lots of fun — in Shea Stadium Remembered. The only thing missing is Basement Bertha, but she was a cartoon drawing immortalized by Bill Gallo. Bertha and Shea had a lot in common — kind of homely, but well-loved. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Anthony Weston, a Nebraska collector who has made a few coffee tables adorned with sports cards:

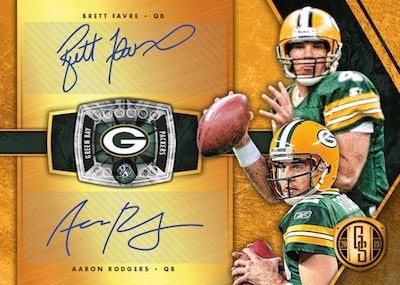

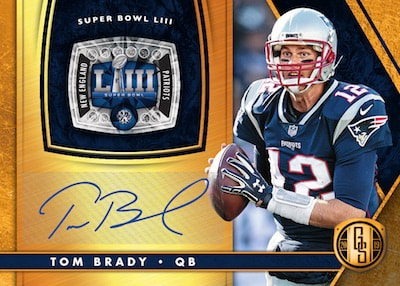

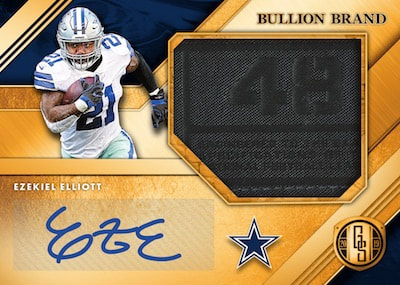

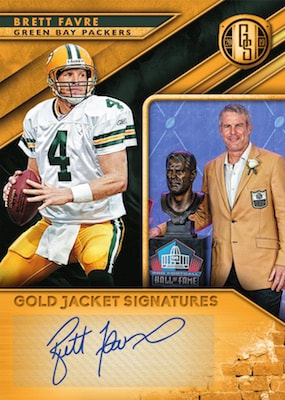

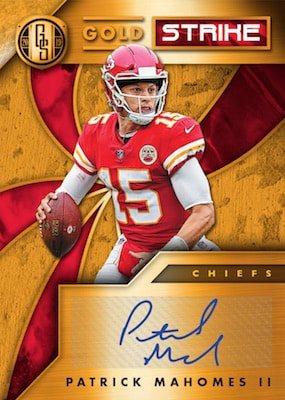

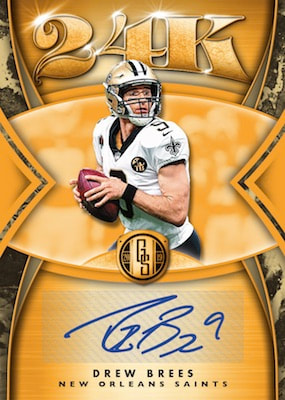

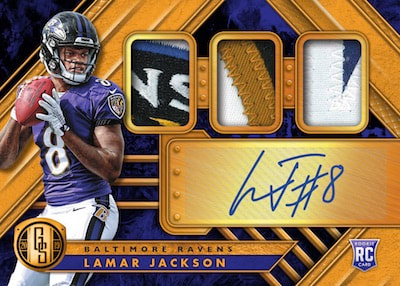

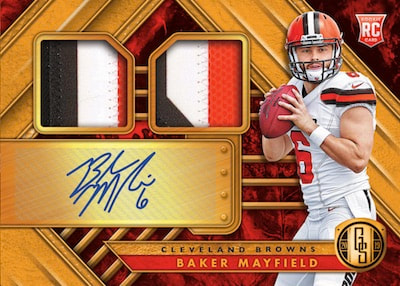

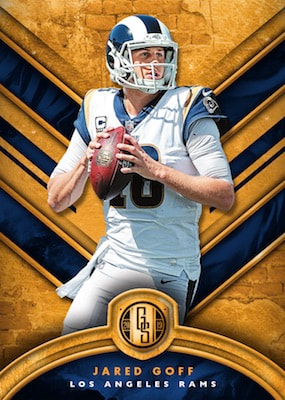

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/in-the-cards-nebraska-collectors-coffee-table-is-tops/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about Panini America's Gold Standard Football set, which will be released in July:

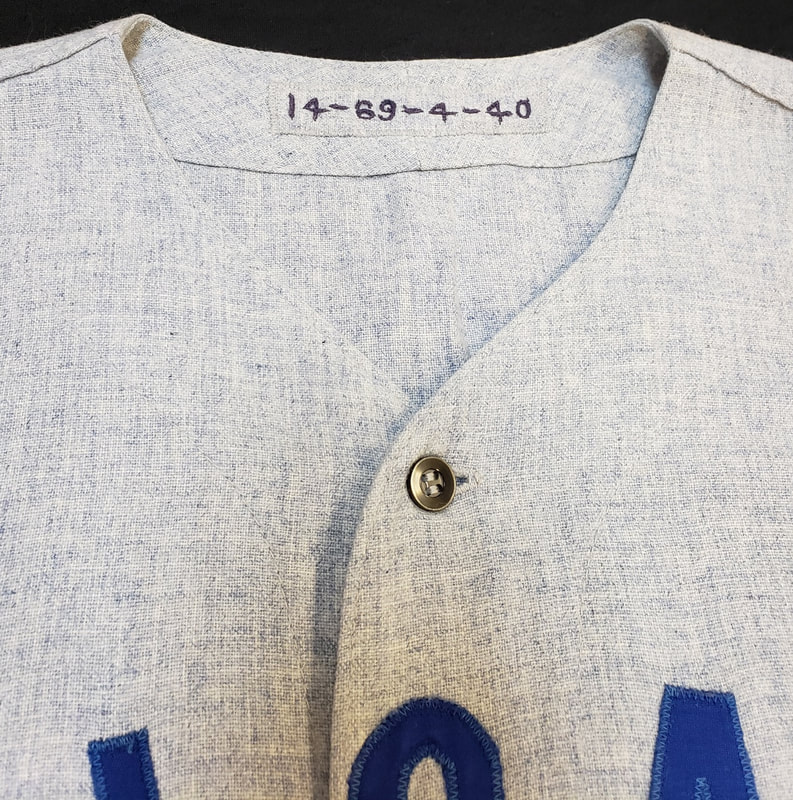

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2019-panini-gold-standard-football-preview/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a 1969 road jersey belonging to Ernie Banks that will be featured in SCP Auctions' Summer Premier sale in August:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/newly-uncovered-1969-ernie-banks-jersey-coming-to-scp-auctions/ |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed