It rarely had to do with the charm of the place, which was basically sterile. Shea did not generate the nostalgia associated with Ebbets Field in Brooklyn or the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan.

But oh, what memories. The Ol’ Perfessor. The Amazin’ Mets. You Gotta Believe. The Fab Four. Broadway Joe. From 1964 until 2008, there were countless memories in Queens.

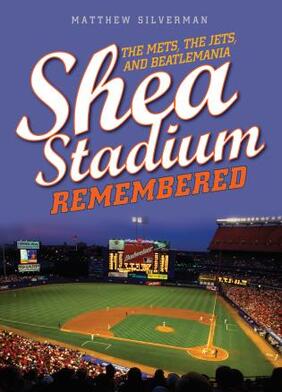

Those moments are what Matthew Silverman pulls together in his tribute to the old ballpark in Flushing Meadows, Shea Stadium Remembered: The Mets, the Jets and Beatlemania (Lyons Press; hardback; $29.95; 232 pages). The book contains 61 chapters and an appendix, and plenty of fun facts and sentimental journeys.

Silverman has plenty of Mets-related books under his belt, including Mets Essential: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Fan (2007), 100 Things Mets Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die (2008), Mets by the Numbers (2008), Shea Goodbye, with Keith Hernandez (2009), New York Mets: The Complete Illustrated History (2011) and Best Mets (2012).

Silverman certainly knows his stuff when it comes to the Mets, and he is equally knowledgeable about Shea Stadium. He confessed he has nostalgia about the old structure, “which is imagination backwards.” Who can blame him?

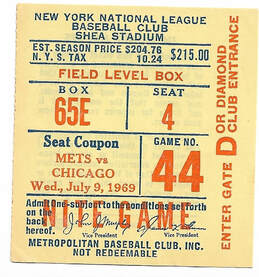

My first trip to Shea Stadium was June 17, 1967, and the Mets (19-37) were hosting the Chicago Cubs (31-26). My father was the Cubmaster for Pack 222 in Brooklyn, and he got the bright idea of taking his Cub Scouts on a field trip to Shea Stadium.

My dad was always coming up with field trips — to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, West Point (our bus broke down in the snow just past Yankee Stadium), Coney Island, Consolidated Edison in Manhattan (we had lunch at a Horn and Hardart automat), the Gil Hodges Bowling Lanes in Brooklyn, Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay and the Vanderbilt Museum in Centerport.

But Shea Stadium was his most ambitious project, because he, along with maybe five or six chaperones, was taking 30 kids on the subway from Brooklyn to Queens. Miraculously, nobody got lost. We sat in the third deck by the right field foul pole. Miraculously, nobody fell out of the stands.

The Mets lost, not so miraculously, 9-1, with Bill Denehy taking the loss. Denehy, who is a footnote for baseball card collectors because he shares a 1967 Topps rookie card with Hall of Famer Tom Seaver, is now blind and living in the Orlando, Florida, area, where in March he said his caretaker allegedly stole more than $17,000 from him.

That’s a sad footnote.

Silverman’s book, on the other hand, is upbeat. The early Mets were lousy, but they “offered fun.” There was Banner Day, when Mets fans would parade around the stadium with bedsheet banners, and the ultimate sign-maker, Karl Ehrhardt, who told the Journal News of White Plains in 1970 that he had 705 different signs in his inventory. One could say these fans traced their ancestry from the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Sym-Phony Band and the cowbell-clanging Hilda Chester.

There was Mr. Met, the team’s mascot, and Mets manager Casey Stengel, who doubled as the team’s cheerleader, talking in circles but promoting the team with every fractured bit of syntax.

Silverman bounces off some good lines in his prose, comparing Mets fans’ attendance at Dodgers and Giants games — the former teams they rooted for — to “going to dinner with your ex at your neighbor’s house.”

He gives the reader some fun facts, too. For example, Shea Stadium’s first chief electrician, Lou Beal, estimated the candlepower of Shea Stadium’s lights were 2,341,000 — making the field “bright as day,” even at night. And despite the constant planes flying over Shea into nearby LaGuardia Airport, there was only one fatality — in 1979, during the halftime of a New York Jets-New England Patriots game, when a radio-controlled plane — in the shape of a lawn mower — went out of control and struck two fans. One of the fans, John Bowen, died several days later from his injuries.

“Though sad, it is ironic that of the countless thousands of planes of every size and shape that flew over Shea, the lone fatality involved a radio-controlled flying lawnmower,” Silverman writes.

There was the Kid, Mex, Doc and Straw. Jesse Orosco throwing his glove skyward after the final out of the 1986 World Series (did it ever come down?), and the Subway Series returning to New York in 2000 after a 44-year hiatus.

The only real glitches in this book are Silverman’s erroneous labeling of the popes who came to Shea. He writes that Pope John Paul XVI became the first pontiff to visit the United States in 1964 (it was Pope Paul VI) and Pope John II came in 1979 (it was Pope John Paul II).

Through good times and bad, Shea Stadium weathered it all.

“The Mets at Shea were 44 acts in a very long Greek tragedy,” Silverman writes.

Silverman documents all the comedy, tragedy, drama — and lots of fun — in Shea Stadium Remembered. The only thing missing is Basement Bertha, but she was a cartoon drawing immortalized by Bill Gallo. Bertha and Shea had a lot in common — kind of homely, but well-loved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed