www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-bowman-baseball-will-tout-70th-anniversary/

|

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the upcoming 2017 Bowman baseball set: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/2017-bowman-baseball-will-tout-70th-anniversary/

0 Comments

Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the arrest of three men accused of stealing more than 400 NBA game-worn jerseys:

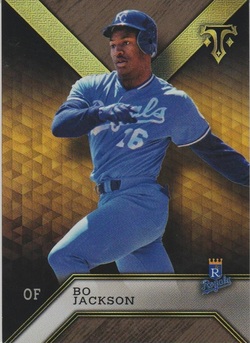

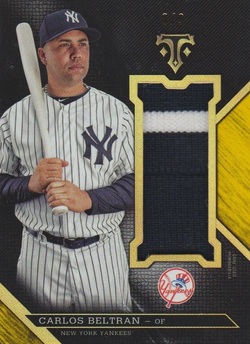

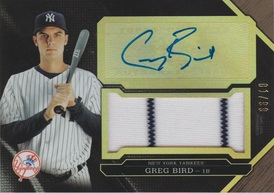

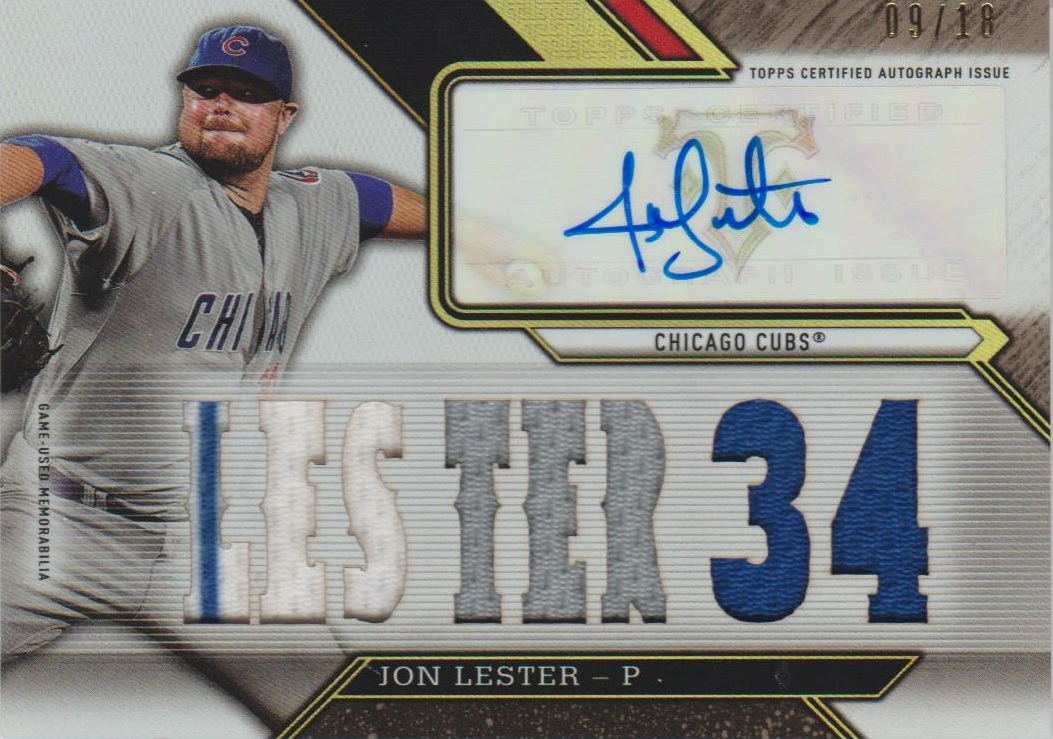

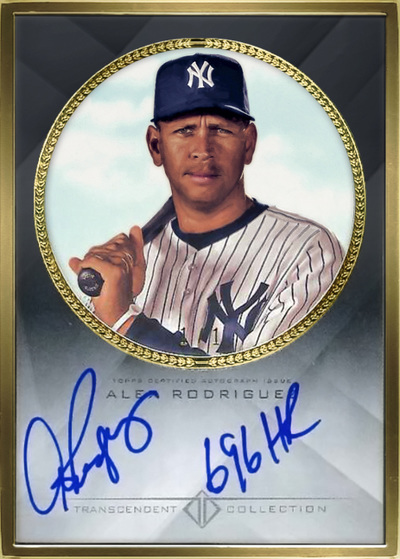

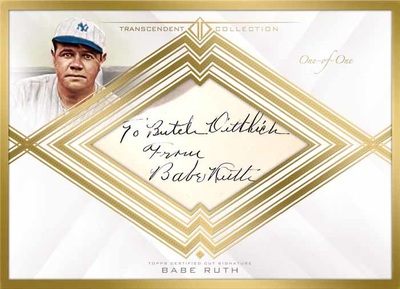

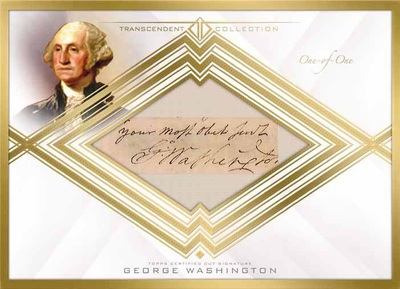

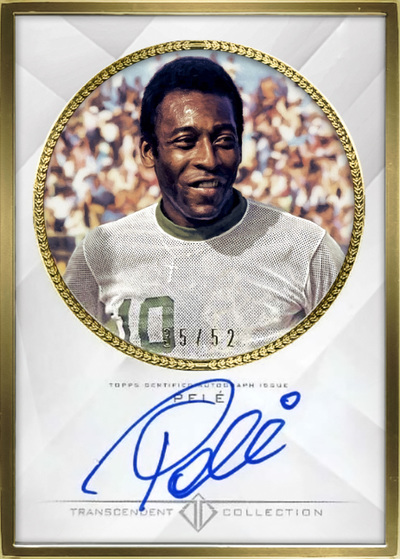

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/meigray-jersey-theft-arrests/ Topps Triple Threads is one of those sets collectors either love or hate. Collectors who enjoy the product point to the thick stock, autographs and interesting relic configurations. Critics point to sticker autographs some of the relics that have names cut into them that can be rather silly at times. Regardless, Topps has stuck with the same formula through the years, and it works.  A master box contains two mini-boxes, with seven cards per mini. Topps promises an autograph card and a relic in every mini-box, so those who buy master boxes should expect to get two of each. Expect to pay around $170 per master box, depending on the retailer. The base set includes 100 cards and features a nice sprinkling of current stars, promising rookies and Hall of Famers. There are parallels, of course, with amethyst (numbered to 340), emerald (250), amber (150), gold (99), onyx (50) and sapphire (25). There also are 1/1 ruby parallels and 1/1 printing plate cards. The base card design showcases a cutout action shot of the player (although some are reminiscent of the posed shots Topps used during the 1960s), with a gold background. The Topps Triple Thread logo is at the top of the card, either on the left- or right-hand side, and the player’s name is near the bottom of the card, flanked by his position and the team logo. Card backs feature a “Triple Take” that lists three key facts about the player.  The mini-boxes I opened were average in distribution — three base cards, two parallels, an autograph and a relic. The first pack held base cards of Bo Jackson, David Ortiz and Todd Frazier. The parallels were an amethyst card of the Blue Jays’ Josh Donaldson and an amber parallel of Rays pitcher Chris Archer. The memorabilia card was a Unity Jumbo Relic of Yankees outfielder Carlos Beltran, gold parallel numbered to 9. It’s a nice, generous swatch, mostly black with a white pinstripe. The autograph card was a timely one, as it was a Triple Threads Autograph Relic card of Cubs pitcher John Lester, who lost Game 1 of the World Series on Tuesday and hopes to rebound tonight in Game 5 to keep Chicago alive in the best-of-seven series. The card was numbered to 18, and the uniform swatch was behind a die-cut rendering of Lester’s name and uniform number.  The second pack’s base cards included Mike Trout, Jackie Robinson and Aaron Nola. The parallels were a pair of Hall of Famers: an amethyst card of Lou Gehrig and an onyx version of George Brett. The relic card was true to the product name, as it was a Triple Threads Relic Combo card of the Mets’ Curtis Granderson, Matt Harvey and Michael Conforto, numbered to 27. Parallels for this subset can be found in emerald (numbered to 18), gold (9) and sapphire (3). There are 1/1 parallels in ruby, wood and White Whale Printing Plates. The signature card was another Unity Jumbo Relic. This one pictured Yankees first baseman Greg Bird, numbered to 99. The swatch was much more “Yankees” defined than the Beltran card — this card had a pair of blue vertical pinstripes set against a generous swatch of white. One of the special additions to this year’s Triple Threads product — actually, it is a continuation of Topps’ yearlong promotion — are autographs from Crash Davis. Davis, of course, is actor Kevin Costner, who starred in the baseball movie classic “Bull Durham.” There are plenty of rookie autographs to be found (although I didn’t pull any), but honestly I prefer the veteran and Hall of Fame signatures. Some collectors will be lucky enough to pull 1/1 bat knob, laundry tag and bat nameplate books, too. But once again, Triple Threads delivers a nice-looking product. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 2016 Topps Transcendent baseball set, an ultra-premium product limited to 65 briefcases:

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/transcendent-collection-is-topps-ultimate-high-end-product/ Here is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a Steiner Auction event that featured Yogi Berra memorabilia. Berra's 1953 World Series Ring sold for slightly under $160,000.

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/yogi-berra-rings-sold-for-159k-at-steiner-sports-auction/ This is a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the Washington State Sports Collectors Association card show, an annual event in the Seattle area: www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/washington-state-sports-collectors-show/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the annual card show in San Leandro, California, held at the St. Leanders Church since 1985.

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/san-leandro-california-card-show/ Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about a "Shoeless" Joe Jackson bat that fetched more than $583,000 at an auction Wednesday in New York.

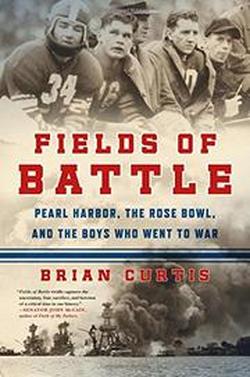

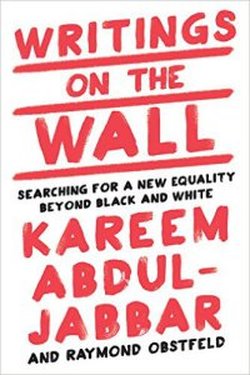

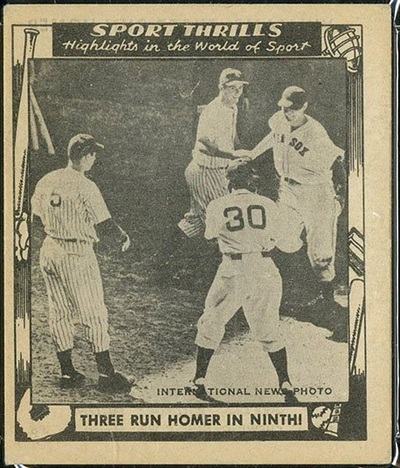

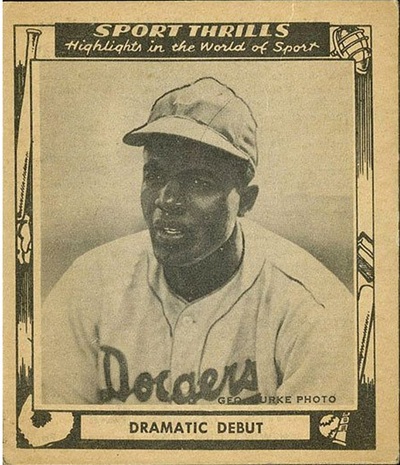

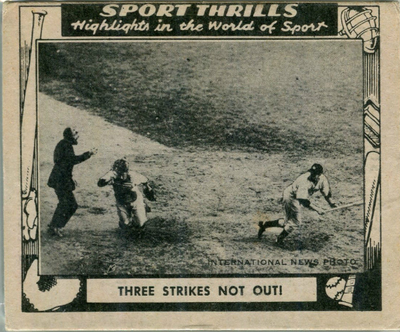

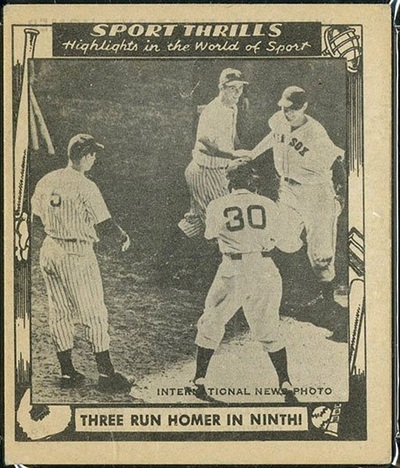

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/shoeless-joe-jackson-bat-fetches-583k-at-christies-auction/  It reads like a script from the old television show “Cold Case.” A former heavyweight boxing champion is found dead from an apparent heroin overdose. Undertones of organized crime and racial tension rage in Las Vegas. A police informant points a finger at rogue policeman, then is found dead under mysterious circumstances years later. Maneuvering, wrangling and jealousy between the area’s two biggest law enforcement agencies run rampant. Charles “Sonny” Liston’s death in January 1971 has been chalked up to that accidental overdose. But in The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights (Blue Rider Press; hardback; $27; 304 pages), author and investigative journalist Shaun Assael advances a more sinister theory. Liston, he asserts, was forcibly injected with an overdose of heroin. “Can you tell me what happened to you, Sonny?” Liston’s widow, Geraldine shouted at his funeral. That’s the question Assael attempts to answer. He builds his narrative slowly, step by step, taking the reader into the culture that Liston had thrived in during the late 1960s. There are so many seedy characters in this book, it would be easy to point the finger at a number of people — and Assael explores each “suspect” in detail. But any mystery has a beginning, and Liston lived a hard life from the start. Born in Forrest City, Arkansas, and one of the 25 children fathered by a sharecropper named Tobe Liston — “a miserable miscreant of a man” — Sonny ran afoul of the law as a youth after his mother moved the family to St. Louis in the mid-1940s. He was introduced to boxing by a prison chaplain who was impressed by Liston’s fearsome jab, a left-handed punch that trainer Angelo Dundee compared to “getting hit by a telephone pole.” But even though Liston had the biggest fists in boxing history, “his fate would always be in someone else’s hands.” Liston won the heavyweight title with a crushing knockout of Floyd Patterson in the first round of their 1962 bout and did the same in the return bout a year later. He lost the title to Cassius Clay (who would become Muhammad Ali) in February 1964, and in the May 1965 rematch at Lewiston, Maine, Liston was knocked out in the first round by what some observers called a “phantom punch.” Assael writes about a “secret percent theory,” where Liston would receive a cut of Ali’s future earnings in exchange for him taking a dive in the rematch. It was plausible; Liston could settle into semi-retirement and still live a good life on the strength of Ali’s success. But nobody could anticipate Ali’s future controversy over his refusal to be inducted into the military. Assael writes that Liston’s head told him to stay in his suburban Vegas home and keep his wife happy, but “his heart kept leading him to the boozy, shiftless soul” of the Las Vegas ghetto. He became an enforcer for a drug dealer named Robert Chudnick — also known as jazz musician Red Rodney. In February 1969, Liston was the only person released when police raided and arrested everyone in the home of a beautician/drug dealer named Earl Cage. Chudnick and others in the drug business began to view Liston with distrust, believing he might be a police informant. Apparently, Gage thought so, too. Liston’s death in 1971 didn’t have the earmarks of a murder. The autopsy was inconclusive, and news reports at the time played up Liston’s descent into drug addiction. Death by overdose seemed to be a natural progression. But in 1982, a police informant named Irwin Peters claimed that former Vegas cop Larry Gandy had killed Liston. Gandy had been a legend among Las Vegas law enforcement workers, setting up more than 100 drug dealers, gaining their confidence by “shooting up” heroin with them. But Gandy had substituted gel caps filled with maple syrup and swapped them with the real stuff. He had been fired for insubordination and turned crook, and eventually would be sentenced to 10 years in jail. The sentence was suspended. Peters, by the way, received an ominous postcard with a picture of a desert and a threat: “This is where you’ll be.” Peters would be found dead in his garage in 1987, his car engine running. Gandy proved why he was a legend, taking the initiative when Assael knocked at his door. “Gandy wrapped his thick arm around me and said, ‘So, you’ve come to ask me if I killed Sonny Liston,’” Assael writes. | Assael said Gandy then kept him “spellbound” for the next two hours as he talked about his career and the crimes he later committed. He pointed to Gage as the man who killed Liston. “As Gandy leaned backward, calm as could be, it suddenly struck me that this was the reason he had invited me into his home,” Assael wrote. “He’d spent the last thirty years trying to outrun Irwin Peters’ allegations. “Now, while he had a chance, he wanted to offer up his own suspect. A dead beautician.” (Gage died in 2000). The Murder of Sonny Liston offers up plenty of theories, and Assael is thorough as he sifts through them. In the end, however, Assael is unable to prove anything. “I believe that finding the killer of Irwin Peters will unravel the real story of what happened to Sonny Liston,” he writes. That may never happen. But Assael has pulled back the glamorous veneer of Las Vegas to reveal its sordid, seamier side. It’s a fascinating read.  Brian Curtis is not just snapping off a crisp phrase when he writes that the 1942 Rose Bowl was “a game remade by infamy.” The game was played less than a month after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, and for the only time in its history, contested away from Pasadena, California. It very nearly wasn’t played, and it pitted two unlikely teams. In Fields of Battle: Pearl Harbor, the Rose Bowl, and the Boys Who Went to War (Flatiron Books; hardback; $29.99; 310 pages), football is the common denominator. But the grit, courage and discipline shown by the men who played for Duke and Oregon State extended far beyond the gridiron. Curtis has written seven books and is currently working on a new book with Craig Sager about the longtime sportscaster’s battle with leukemia. In his latest effort, Curtis looks back on a tense period in American history. Fields of Battle is a nice play on words, since Curtis is writing about college football as the Great Depression ended and the drumbeats of war as the United States moved closer to military conflict. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, came a week after unbeaten Duke (9-0) and Oregon State (8-1) were extended invitations to the Rose Bowl. Lt. Gen. John Lesesne DeWitt, commander of the Fourth Army and the man responsible for security on the West Coast, quickly moved to have the game canceled. He believed that a large crowd at the Rose Bowl was too tempting a target for the enemy. After some negotiations, the game was revived and shifted east to Durham, North Carolina, where the Rose Bowl would be played on a rainy, chilly New Year’s Day. Oregon State prevailed in a hard-fought game to upset the Blue Devils, 20-16. That is one aspect of Fields of Battle. Curtis does a nice job with his narrative, introducing the players, coaches and recapping their seasons. Where he excels is in the telling of the aftermath of the game. More than 70 players and coaches who were involved in the 1942 Rose Bowl would enter the military. Some fought in the Pacific, distinguishing themselves at Iwo Jima, Okinawa and Guadalcanal; others landed on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day; still others showed bravery during the desperate German offensive that became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Four men would die during the war. The stories Curtis tells are riveting. Oregon State’s Frank Parker and Duke’s Charles Haynes were Rose Bowl opponents but comrades in Italy, serving for the 349th Infantry Regiment. Parker would save Haynes’ life, dragging him to safety after the former Duke player was shot and was bleeding from “a hole in his chest the size of two fists.” In a letter he wrote to a Duke coach during the War, tackle Bob Nanni conceded that “war is the same as a football game.” “The one that hits the hardest first, will win,” he wrote. Months later, as he was on patrol on Iwo Jima, Nanni was killed by Japanese snipers. “He never heard or saw it coming,” Curtis writes. On the same island, Oregon State halfback Bob Dethman led a platoon during a firefight at close range, withstanding grenades, suicide attacks and shootouts to hold their position. Dethman would earn a Bronze Star for his actions. Dethman would have a difficult life after the war, losing his 22-month son when the boy ran behind a car his mother was backing out of the driveway and was killed. Dethman became an alcoholic, and later died when he drowned trying to save one of his dogs that had become trapped in the waters of a rushing river. Duke coach Wallace Wade would serve overseas, but not before coaching a group of Army All-Stars against National Football League teams during the summer of 1942. The most difficult story to digest in this book was that of Chiaki “Jack” Yoshihara, a Japanese-American who played for Oregon State. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Yoshihara was summoned by Oregon State coach Lou Stiner, who was in the company of two FBI agents. The agents questioned Yoshihara about his background and allegiances, and then told him that by presidential order he was “an enemy of the state” and was not allowed to attend the Rose Bowl game in North Carolina. Curtis writes that “life had been different” for the American-born Yoshihara in the days following Pearl Harbor, but while he “was able to cope with unwanted stares, dirty looks, and even whispers behind him in class,” the decision to keep him out of the game was a move that made the Japanese-American experience “real.” Yoshihara tried to enlist, but was denied, shunned by the country of his birth because of his heritage. In a happy but belated postscript, Oregon State would award Yoshihara his college degree in 2008. Fields of Battle is a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by young men and women during World War II. The players and coaches were affected, but so were their families. Football is often used as a metaphor for war, but the reality is much harsher. Curtis does a nice job in bringing the reality into sharper focus. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 20-card Sport Thrills set from 1948:

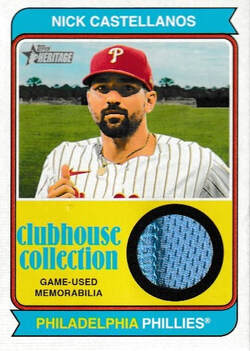

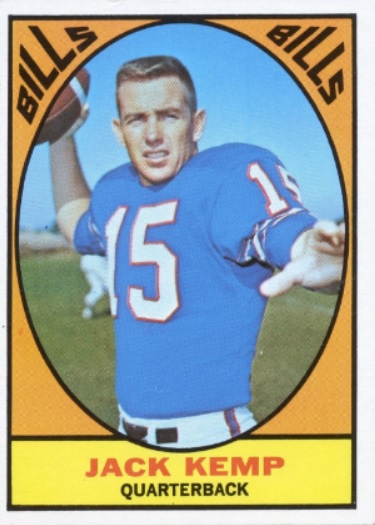

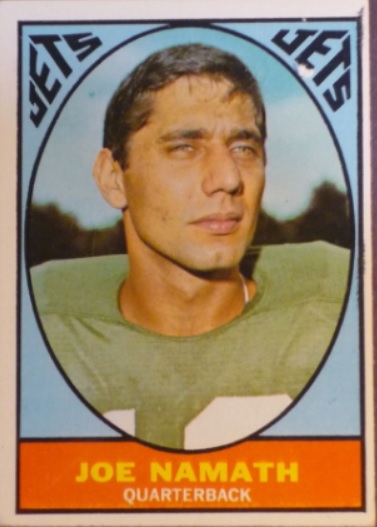

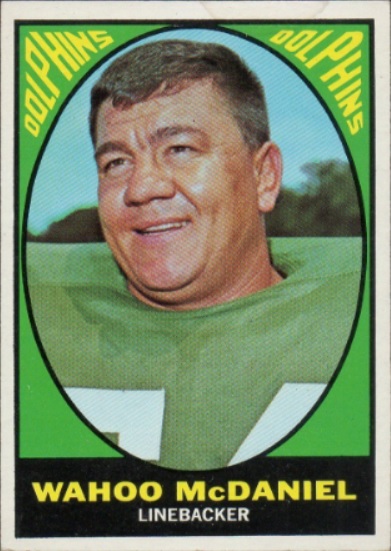

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1948-sport-thrills-scarce-packed-with-stars/  Using the classic 1967 design, Topps gives minor-leaguers the full treatment in its 2016 Heritage Minor League baseball set. The set is a little bit smaller this year. Like last year, there are 200 base cards — but there are only 15 short prints in the 2016 version, as opposed to 25 last year. There is also one autograph and a relic in a hobby box; for the past few years, Topps was promising two autograph cards and a relic. The good news is that this year’s autograph is an on-card signature. A hobby box for 2016 contains 18 packs, with eight cards per pack. Price for a hobby box will be in the $50 range, depending on the retailer. Unless you are a prospect geek, many of the names in this set will not be familiar ones. The one thing I do enjoy is the team names. There are so many interesting ones. Here’s a sampler: the Hartford Yard Goats, Akron Rubberducks, Modesto Nuts, San Antonio Missions, Jackson Generals, Augusta Greenjackets, Louisville Bats, Lehigh Valley Ironpigs and the Montgomery Biscuits. In addition to players in the base set, there are also League Leader cards. Parallels include blue borders, numbered to 99, peach borders (25), black (1/1) and printing plates (1/1). There were three blue bordered cards in the box I sampled. The autograph card I pulled was of pitcher Kolby Alland, who played for the Gulf Coast League Braves when the photo was taken. He has since been promoted to Rome of the South Atlantic League, where he went 5-3 with 62 strikeouts and 20 walks. The relic card I pulled was a Clubhouse Collection, gray uniform swatch of Memphis Redbirds pitcher Alex Reyes, who went 4-1 with a 1.57 ERA when he got called up by the St. Louis Cardinals. One of the insert sets — the 50-card Topps Stickers — is a mirror image of the original 1967 sticker set, although the 2016 version is not a sticker. I pulled six of these cards. The other insert is the 15-card Minor Miracles, which highlights unlikely efforts by players. I pulled three of those cards. For collectors who dream of pulling on a uniform, the “Make Your Pro Debut” promotion is back. This year, the winner will be able to sign a pro contract with the El Paso Chihuahuas minor-league squad, and take batting practice with the team. Also, the winner will get his or her own baseball card for the 2017 Topps Heritage Minor League baseball set. The 2016 Topps Heritage Minor League baseball set has a clean, crisp look — just like the original 1967 set. It’s a nice way to collect cards of players who might make it to the majors someday. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1967 Topps football set:

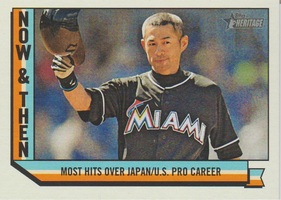

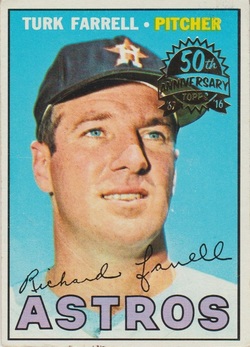

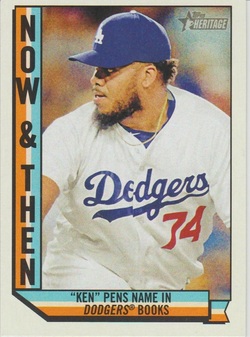

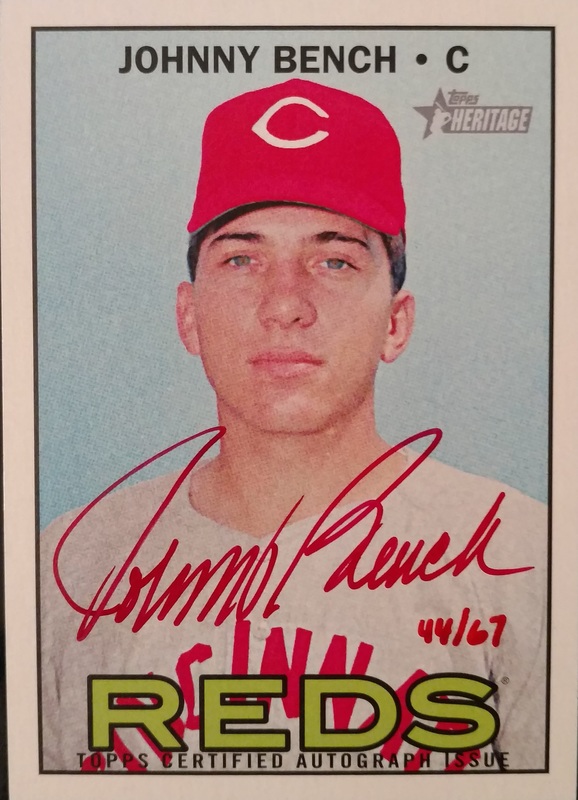

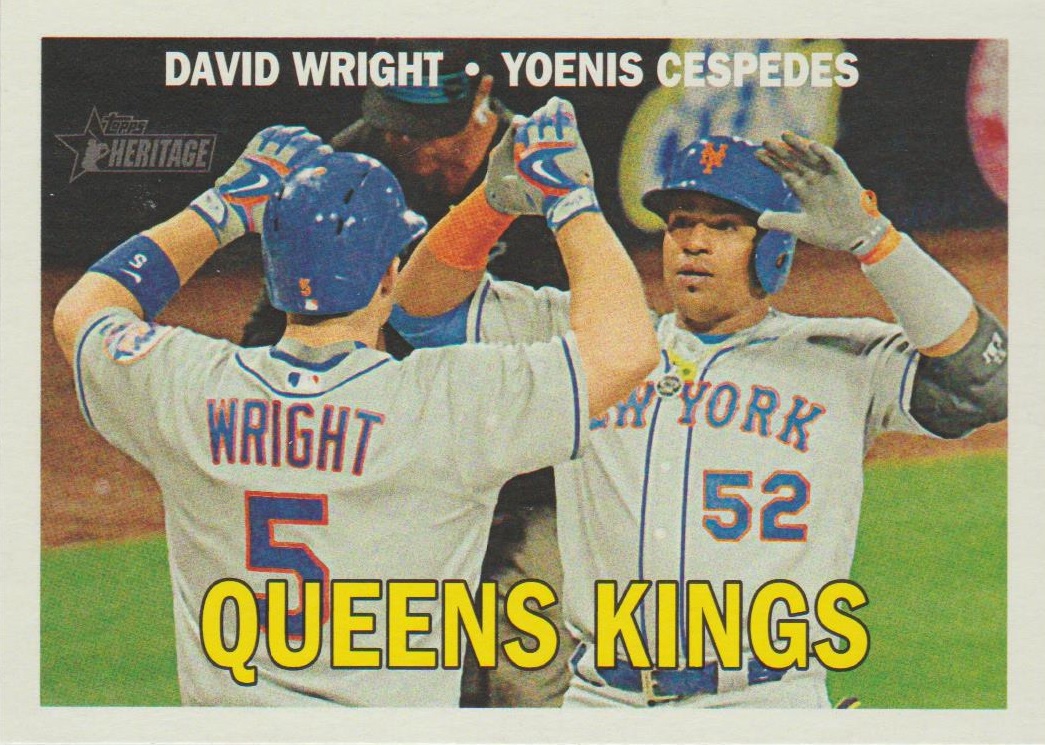

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1967-topps-football-set/  Topps continues its march through the 1967 season with its retro-looking Heritage High Numbers baseball set. The high numbers set is a nice catch-all for players that joined new teams via trade or free agency, or rookies that have made an impact but were not included in the original Heritage run earlier this year. The format is much the same as the basic Heritage set. A hobby box will contain 24 packs, with nine cards per pack. Topps is promising either one autograph or relic card in every hobby box. There also is a guaranteed box loader, which could be a foil-stamped original card from the 1967 set. The other possibilities are three-card ad panels from 1967, or a Punchboard card numbered to 50. The Punchboards have parallels, too with Jumbo Patch Relics numbered to 25, autographs numbered to 10 and Jumbo Patch Relic autographs (also numbered to 10). My box loader was a buyback, stamped foil card of Astros reliever Turk Farrell, who was an original member of the Houston franchise in 1962. Farrell had been a starter but was sent to the bullpen when he was traded to the Phillies during the ’67 season.  The base set is 225 cards, with the final 25 being short prints. I noticed that the backs of cards Nos. 701-725 had a slightly lighter green tint than the other 200 cards. Almost a faded look. The short-printed cards appear once in every three packs, and the box I opened contained the average amount — eight. One of the short prints I found was a Flip Stock card of Blue Jays pitcher Aaron Sanchez. While most of the cards from this set have a smooth front and a rough back, the Flip Stock card reverses the texture. You can see the shiny back when you tilt the card. Topps also offers card variations, too. The ones I pulled were of the Cubs’ Ben Zobrist, and this was a posed image shot (base) and an action shot (variation). What’s interesting about these cards are not the same numbers. The Zobrist base card is No. 564, while the variation held No. 668. Weird. Another variation shows different colors for the team names featured in block lettering. The design of the original 1967 Topps set was the cleanest and crispest of the decade, with a large photograph unencumbered by logos and designs and background borders. The card was basically a shot of the player—some oversized mug shots, others posed “action” shots — with the player’s name and position at the top of the card and the team name in colorful block letters at the bottom. It’s a gorgeous, but simple design.  I pulled 197 base cards from the hobby box that Topps provided, but the card that really caught my attention was the promised big hit. And it was a nice one — an on-card Real One Special Edition autograph of Reds Hall of Fame catcher Johnny Bench in red ink, complete with the serial number also hand-printed in red. In one quirky pack, I pulled back-to-back cards of pitchers Matt Bush (Rangers) and Matt Buschmann (Diamondbacks). There are 50 chrome cards that are parallels to corresponding cards in the base set and are numbered to 999. I pulled a card of Dodgers pitcher (and former Rays ace) Scott Kazmir. There also was a chrome refractor card of Pirates pitcher Jameson Taillon, numbered to 567.  There are four different inserts in this set. Combo Cards is a 20-card subset that pairs two players from a certain team and a highlight moment. I pulled three of those cards. Award Winners contains 10 cards, and I also found three of those. Rookie Performers is a 15-card subset that honors the top first-year stars, while Now and Then is a 10-card offering that notes a player’s performance in early 2016 and then provides a notable feat that occurred on the same date in 1967. I pulled three of each of these two inserts. While the Bench autograph was the highlight of the box I opened, other collectors may find hobby exclusive Real One Dual Autographs, numbered to 25. If relics are your thing, the venerable Clubhouse Collections relics set returns, with Dual Relics numbered to 64, Triple Relics (25) and Quad Relics (10). Autograph Relics (numbered to 25) and a hobby-exclusive Dual Autograph Relics (numbered to 10) round out the hot cards available.  The Heritage High Numbers set extends the main Heritage set and presents a clear, clean look to the 1967 set. Some of those high numbers from the original ’67 set still elude me. I need 13 more high numbers to complete that run, which would give me complete sets from 1964 to the present. Despite their beauty, the 1967 originals tended to be condition sensitive (at least in my neighborhood). So it’s nice to see a 2016 version that looks so much nicer. Now, burlap fans can get ready, since next year’s Heritage product will pay homage to the 1968 set. It’s not as clean-looking as the ’67 set, but those burlap-looking borders certainly make that set distinctive.  Golf has been blessed with so many good writers through the years, authors like Herbert Warren Wind, Dan Jenkins, John Feinstein, James Dodson and Neil Sagebiel. At the newspaper level, as a young sportswriter in Florida during the 1980s I was fortunate to watch and learn from some of the finest reporters in the business: Dave George, Larry Dorman, Tim Rosaforte, Bob Fowler, Craig Dolch, Bob Harig, Larry Bush and Don Coble. The list is not meant to be all-inclusive, but that’s a pretty talented, solid group of writers. What made these writers excel was their ability to let the event tell itself. There was no need to embellish or use hyperbole, and while the prose of some of golf’s best writers seems lyrical, it’s also never forced. That is where Jim Moriarty excels in his new book. Playing Through: Modern Golf’s Most Iconic Players and Moments (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $34.95; 274 pages) puts the reader inside the ropes and in the heads of some of the best golfers of the past 35 years. Moriarty was a contributing writer and photographer for Golf Digest (1985-2001) and Golf World (2001-2015), so he saw some of the top players of what he terms “modern golf.” Moriarty put together 12 essays for Playing Through, starting with a piece on the 1982 U.S. Open that featured Tom Watson’s iconic chip-in at Pebble Beach that sealed his victory and further cemented his rivalry with Jack Nicklaus. It was a match played with wooden clubs, steel shafts and forged irons, Moriarty writes, and “two of the game’s all-time great champions … took each other’s measures one final time.” In between, there are stories about Tiger Woods, Seve Ballesteros, Greg Norman, Payne Stewart, Juli Inkster, Nick Faldo, John Daly, Phil Mickelson and Nicklaus. He also writes about today’s emerging stars, like Rory McIlroy and Jordan Spieth. Here are some fun facts I found about Spieth, from the MoneyNation website. Spieth’s net worth is $77.4 million. Count endorsements, and since 2012, the 23-year-old Spieth has made more than $147.5 million. He makes in one day what most Americans make in three years, the website. But before you lament how golfing greats like the late Arnold Palmer did not make as much money on the tour as newcomers like Spieth — and that’s a fact — understand that Arnie’s endorsements and golf design companies made him worth more than $675 million. That’s nearly nine times more than Spieth. But I digress. Moriarty’s writing takes the reader into the nationalistic pride that bubbles over during the Ryder Cup. That international exhibition between a U.S. squad and a team of Europeans really resonated with me, since I covered the 1983 event at PGA National in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida (Moriarty refers to the course as being in West Palm Beach, but that was incorrect — one of the few glitches in the book). That was the exhibition that showed the European team on the verge of breaking through and ending the United States’ stranglehold on the Cup. What was memorable — and Moriarty recounts it perfectly — was Ballesteros’ shot out of the sand trap at No. 18. Using a 3-wood, Ballesteros hit his shot to the fringe of the green and then got up and down to halve his match with Fuzzy Zoeller. The Europeans lost the competition 14½ to 13½, but the outcome was in doubt through much of the weekend and Ballesteros’ shot kept the final result tenuous until the final match. It was a fun trip down memory lane. Moriarty’s prose is crisp. He notes that Nick Faldo’s critics complained that while he had won three majors, “he hadn’t done anything special to merit any of them other than hang around like a vagrant on a lamppost.” Or this: Scott Hoch “spent so much time looking over his putt at the tenth, it was like he was reading Atlas Shrugged instead of a two-footer.” “Few players ever squeezed so much out of a golf game,” Moriarty writes about Inkster, “and fewer still ever made the game of golf so much better for it.” Moriarty’s longest essay is about Woods, and he devotes a mere four pages to Daly. But his final story served as a bookend to the Watson-Nicklaus duel at Pebble Beach that opened Playing Through. He writes that McIlroy, Spieth and Jason Day were players who had “outsized ability” and “candid honesty.” “They were humble in victory, dignified in defeat, and formidable in competition,” he writes. “The torch had passed into generous hands. “And more were on the way.” Moriarty has provided a neatly presented look at golf since the early 1980s, writing about the sport’s triumphs and tragedies with passion and nuance. It’s a valuable reference and an enjoyable read for golf fans.  The main title of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s latest book comes from “Superstition,” the 1972 hit song by Stevie Wonder that also was featured on his album, “Talking Book.” The album title is certainly appropriate for Abdul-Jabbar’s social examination of American mores and values, too. It is certainly a book worth talking about. In Writings on the Wall: Searching for a New Equality Beyond Black and White (Liberty Street; hardback; $27.95; 245 pages) Abdul-Jabbar wants the reader to stop and think. It doesn’t matter what your political leanings might be; some will agree wholeheartedly with the NBA’s all-time scoring leader, and others are just likely to disagree with Abdul-Jabbar’s conclusions. But that’s not the point. In Writings on the Wall, Abdul-Jabbar not only gives his own opinions — which are unabashedly liberal — he also is willing to listen to other points of view. Ah yes, listen. What a novel idea. One can listen and still disagree. Abdul-Jabbar, assisted by perennial co-author Raymond Obstfeld (who has co-written five books with Kareem) writes about sports of course, but also about race, gender and religion. He backs up his opinions with surveys, research, scholarly works and political polls. It’s almost like reading a college term paper; one is waiting for the footnotes at the bottom of the page. That speaks to Abdul-Jabbar’s thorough approach. When he attended UCLA in the late 1960s, Abdul-Jabbar — still known by his birth name of Lew Alcindor — became a history major. He said he wanted to know why every culture “participated in some form of socially acceptable madness.” That included enslaving people, treating women like property and raining physical abuse on children. “History was like a series of mass hypnosis events in which society was basically a large cult,” he writes.” That love of history — and particularly his desire to present a more well-rounded look at black history — inspired him to write Black Profiles in Courage, Brothers in Arms, What Color is My World? and On the Shoulders of Giants. He is 69 now, and Adbul-Jabbar remains active, He was a cultural ambassador for the United States, appointed by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. He now writes columns and other opinion pieces for the Washington Post, Time and the Huffington Post. In an August 30 column for the Washington Post, Abdul-Jabbar addressed Colin Kaepernick’s decision to sit during the national anthem as a protest against racism. He wrote that “one of the ironies of the way some people express their patriotism is to brag about our freedoms, especially freedom of speech, but then brand as unpatriotic those who exercise this freedom to express dissatisfaction with the government’s record in upholding the Constitution.” The main thrust of Writing on the Wall is that people have to do more critical thinking, no matter what their political leanings might be. He asserts that it’s a process that should begin with children in elementary school. “They must be taught to question every premise, no matter who offers it,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. Liberals are not exempt from criticism. Of President Barack Obama’s suggestion to make voting mandatory, Abdul-Jabbar calls it a bad idea. “We shouldn’t have to persuade people to vote. They should see it as their joyful right and sacred responsibility,” he writes. “When we pressure people to vote, we’re diluting the democratic process by bringing out those who are easily manipulated because they lack any sense of social commitment.” And in terms of racism, Abdul-Jabbar advances the theory that there are two kinds — explicit and implicit. Explicit includes bullying, shaming and offensive language; Abdul-Jabbar compares implicit racism to wallpaper — something in the background, but it’s there, “creating an undeniable tone and mood.” Adbul-Jabbar’s approach to age and mortality is to compare senior citizens to “lottery winners with millions’ worth of experience, figuring out how best to spread the riches.” He refuses to accept the view that his generation should be viewed “like rusty old cars with leaking oil” and “screeching brakes.” Abdul-Jabbar cautions against relying on social media, saying the public’s obsession with it “needs to be tempered.” He concedes the merits of sites like Facebook and Twitter as publicity vehicles; after all, his articles and books gain tremendous exposure when posted or tweeted on those sites. He argues that blurring the line between social media and social science is misleading. “It’s no substitute for professional opinion polling, statistical research and just plain reporting,” he writes. “It’s like forecasting the weather based on a swollen bunion.” He ends the book with an unsolicited letter to America’s Youth. “Each generation must customize the American dream to fit its own circumstances and the realities of the surrounding world,” he writes. “Much of this book has been an indictment of those who preach the gospel of the American dream while secretly doing everything they can to pervert it.” He urges adhering to the Constitution, particularly the parts that “condemn racism, sexism, homophobia and the exploitation of the poor.” It’s something to think about. And critical thinking and opening dialogue is what Abdul-Jabbar is trying to achieve. So whether you find his ideas in Writings on the Wall enlightening or repugnant, critical thinking is what is important. And if people from all points of the political, social and economic spectrum can do that, then there is a chance for real progress. And then the writing will truly be on the wall — a version of American graffiti that promises a positive step. Here's a story I wrote for Sports Collectors Daily about the 1962 Topps football set:

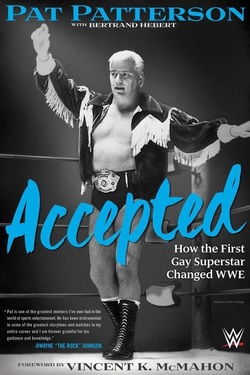

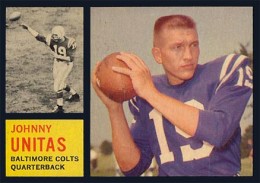

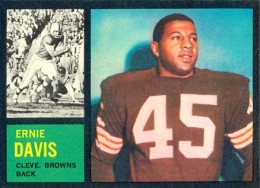

www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1962-topps-football-easy-collect-tough-to-find-in-high-grade/  I’ve always believed that pro wrestlers are the best storytellers. Years of being on the road and working in close quarters with other wrestlers will do that. Sure, Vin Scully can make a grocery list sound poetic (when he read one 40 years ago during a Dodgers broadcast), but a wrestler like Terry Funk can make that same list sound intimidating as his voice quavers in anger. Funk and many other wrestlers have written books about their lives and times. But nobody else in the business has Pat Patterson’s back story. Not only was Patterson a big gate attraction in the 1960s, he also was gay. Pro wrestling in the 1950s was a rough-and-tumble business, and even the hint of something less than a macho heterosexual could be detrimental to a man’s career. One shtick on some wrestling shows was to put the loser of a match in a dress — demeaning his masculinity, so to speak. But the effeminate character worked for Gorgeous George, a headliner in the 1950s who wore elaborate robes; had perfectly coiffed, bleached-blonde curls; and passed out Georgie Pins (since bobby pins were so pedestrian, he explained). But outside the ring, nobody ever admitted to being gay. Until Patterson. In Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE (ECW Press; hardback; $25.95; 258 pages), Patterson mixes in his professional career and personal life in an entertaining narrative. There are plenty of stories that wrestling fans will love, anecdotes about Killer Kowalski, Ray Stevens, Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon, Bret Hart, Hulk Hogan and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. But Patterson also chronicles his 40-year relationship with Louie Dondero, a man of many talents (cook, barber, wrestling valet) who was admired by many in the business. Patterson was never open about his relationship with Dondero, who died of a heart attack in 1999. “We never introduced ourselves as in a relationship or showed affection in public. We were hiding in plain sight,” Patterson writes. “That just goes to show you how deep you needed to pretend back in the day. “Even if things have changed since, I still can’t completely shake it off.” In 2014, Patterson came out on Legends’ House, a WWE reality television show, which depicted him and other wrestling stars living together in a California mansion. “While many people knew I was gay, I had never expressed it in front of a crowd,” Patterson writes. “I was ready to let go of the burden of secrecy.” Patterson is not the only gay pro wrestler. Darren Young came out in 2013, the first active performer to do so. But Accepted is not just about lifestyles. Wrestling fans will learn some of the inner workings of World Wrestling Entertainment and its owner, Vince McMahon Jr. (a classic workaholic who also wrote the book’s foreword). They also will discover more details about Patterson’s life away from the ring. They will read about Patterson’s decision to step down as a WWE vice president after he was accused of sexual harassment. He returned at McMahon’s behest in 1992 after the WWE owner conducted his own independent investigation, and continues as a company adviser. Born Pierre Clermont in 1941 and one of 11 children, Patterson realized he was different. His first gay experience as a teen was an eye-opener. “We were just two people, together, sharing their feelings,” Patterson writes. “It was a strange sentiment. “In fact, I couldn’t see straight.” Patterson left his comfort zone in Montreal and traveled to wrestle in Boston. In addition to being new to the business, Patterson also could not speak English. But his wrestling skills attracted attention, and Vachon moved him west to Portland, Oregon, where he excelled. After a fruitful wrestling tag team career with Stevens (they were AWA world champions at one point), Patterson became the first Intercontinental champion of the World Wide Wrestling Federation (now WWE). He retired as an active wrestler in 1984 and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 1996. Many forget that Patterson was the referee in the main event of the first WrestleMania. Patterson also writes about the pranks he pulled on other wrestlers, his night-time drinking binges in Japan with Andre the Giant, and his battles with promoters like Roy Shire and Verne Gagne. He writes fondly of wrestling colleagues like Lord Alfred Hayes and Rene Goulet, and also recounts his classic 1981 Alley Fight match with Sgt. Slaughter. He praises McMahon’s vision, which made his company the top pro wrestling organization in the world. McMahon “saw wrestling like the world of Disney, with all those characters aiming to be bigger than life,” Patterson writes. And it’s true. Hulk Hogan. The Ultimate Warrior. The Rock. The Million Dollar Man. “Macho Man” Randy Savage. All were great characters that flourished under McMahon’s umbrella. Patterson also gives his side of the infamous “Montreal Screwjob” in the 1997 Survivor Series match that saw Bret Hart “lose” his WWF title to Shawn Michaels by submission, even though it was clear that Hart did not submit. The punch McMahon took in the jaw from Hart after the match was real. “They made sure I wasn’t in the know,” Patterson writes, “because I would have tried to find a way to talk Vince out of it.” Hart believed for many years that Patterson was in on the fix. In his 2007 autobiography, Hart wrote that Patterson approached him during the funeral of his brother Owen in 1999 and tried to convince him that he wasn’t. Hart claimed that Patterson “shut up” when the Hitman asked, “So, where were you when they brought the midget out all dressed as me?” That was a reference to Michaels escorting “a Mexican midget wrestler wearing a leather jacket and a Hitman Halloween mask” to the ring two weeks after the Montreal match. At the time Hart wrote his book, his bitterness with Patterson was evident. For his part, Patterson said he and Hart finally made their peace a few years ago. “Bret had good reason to be angry,” Patterson writes. “Just not forever.” Patterson has been dedicated to the business for nearly 60 years, but it’s the stuff outside the ring that he remembers. “That’s what I look back on most fondly,” he writes. “There’s plenty of them, and they all still make me laugh.” Patterson also discusses his part as one of “the stooges” with Gerald Brisco in the late 1990s, and how he was not enamored with a clownish role. “I was a main-event wrestler and I used to draw thousands of people,” he writes. “I was never comic relief. “It was a hard pill to swallow … but it’s remembered fondly.” Accepted is a funny, warm book. Patterson is a great storyteller and recounts his episodes with relish. He is obviously having a good time throughout most of the book, and he playfully tells readers to skip ahead to Chapter 8 to read about Stevens’ wild life. But he grows serious when he discusses his lifestyle and the business he loves. “No wrestler ever refused to work with me because I was gay,” he writes. “I loved the business, but the business never took over my life. “It was difficult just being me. I never wanted to be branded as ‘just a wrestler’ or ‘just a gay man.’” And that should be acceptable to those who read Patterson’s book. |

Bob's blogI love to blog about sports books and give my opinion. Baseball books are my favorites, but I read and review all kinds of books. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed