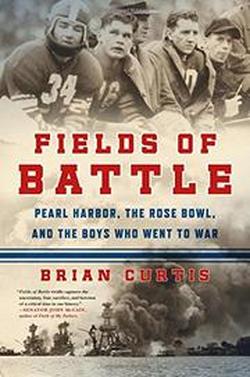

In Fields of Battle: Pearl Harbor, the Rose Bowl, and the Boys Who Went to War (Flatiron Books; hardback; $29.99; 310 pages), football is the common denominator. But the grit, courage and discipline shown by the men who played for Duke and Oregon State extended far beyond the gridiron.

Curtis has written seven books and is currently working on a new book with Craig Sager about the longtime sportscaster’s battle with leukemia. In his latest effort, Curtis looks back on a tense period in American history.

Fields of Battle is a nice play on words, since Curtis is writing about college football as the Great Depression ended and the drumbeats of war as the United States moved closer to military conflict. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, came a week after unbeaten Duke (9-0) and Oregon State (8-1) were extended invitations to the Rose Bowl.

Lt. Gen. John Lesesne DeWitt, commander of the Fourth Army and the man responsible for security on the West Coast, quickly moved to have the game canceled. He believed that a large crowd at the Rose Bowl was too tempting a target for the enemy.

After some negotiations, the game was revived and shifted east to Durham, North Carolina, where the Rose Bowl would be played on a rainy, chilly New Year’s Day. Oregon State prevailed in a hard-fought game to upset the Blue Devils, 20-16.

That is one aspect of Fields of Battle. Curtis does a nice job with his narrative, introducing the players, coaches and recapping their seasons. Where he excels is in the telling of the aftermath of the game. More than 70 players and coaches who were involved in the 1942 Rose Bowl would enter the military. Some fought in the Pacific, distinguishing themselves at Iwo Jima, Okinawa and Guadalcanal; others landed on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day; still others showed bravery during the desperate German offensive that became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Four men would die during the war.

The stories Curtis tells are riveting.

Oregon State’s Frank Parker and Duke’s Charles Haynes were Rose Bowl opponents but comrades in Italy, serving for the 349th Infantry Regiment. Parker would save Haynes’ life, dragging him to safety after the former Duke player was shot and was bleeding from “a hole in his chest the size of two fists.”

In a letter he wrote to a Duke coach during the War, tackle Bob Nanni conceded that “war is the same as a football game.”

“The one that hits the hardest first, will win,” he wrote.

Months later, as he was on patrol on Iwo Jima, Nanni was killed by Japanese snipers. “He never heard or saw it coming,” Curtis writes.

On the same island, Oregon State halfback Bob Dethman led a platoon during a firefight at close range, withstanding grenades, suicide attacks and shootouts to hold their position. Dethman would earn a Bronze Star for his actions.

Dethman would have a difficult life after the war, losing his 22-month son when the boy ran behind a car his mother was backing out of the driveway and was killed. Dethman became an alcoholic, and later died when he drowned trying to save one of his dogs that had become trapped in the waters of a rushing river.

Duke coach Wallace Wade would serve overseas, but not before coaching a group of Army All-Stars against National Football League teams during the summer of 1942.

The most difficult story to digest in this book was that of Chiaki “Jack” Yoshihara, a Japanese-American who played for Oregon State. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Yoshihara was summoned by Oregon State coach Lou Stiner, who was in the company of two FBI agents. The agents questioned Yoshihara about his background and allegiances, and then told him that by presidential order he was “an enemy of the state” and was not allowed to attend the Rose Bowl game in North Carolina.

Curtis writes that “life had been different” for the American-born Yoshihara in the days following Pearl Harbor, but while he “was able to cope with unwanted stares, dirty looks, and even whispers behind him in class,” the decision to keep him out of the game was a move that made the Japanese-American experience “real.”

Yoshihara tried to enlist, but was denied, shunned by the country of his birth because of his heritage.

In a happy but belated postscript, Oregon State would award Yoshihara his college degree in 2008.

Fields of Battle is a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by young men and women during World War II. The players and coaches were affected, but so were their families. Football is often used as a metaphor for war, but the reality is much harsher.

Curtis does a nice job in bringing the reality into sharper focus.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed