Mickey Mantle was my contemporary baseball hero during the 1960s, but Gehrig was the player — and man — I wanted to be: honest, hard-working, muscular and humble. He was the epitome of the New York Yankees.

“He entered the hearts of the American people, because of his living as well as his passing, he became and was to the end, a great and splendid human being,” Gallico wrote.

The 1942 movie, Pride of the Yankees, was similarly sentimental, starring Gary Cooper in the title role as Gehrig in the first real biography movie about an athlete. It immortalized Gehrig’s famous and emotionally charged “Luckiest Man” speech he gave on July 4, 1939, at Yankee Stadium, and also showed the love story between the slugger and his wife, Eleanor.

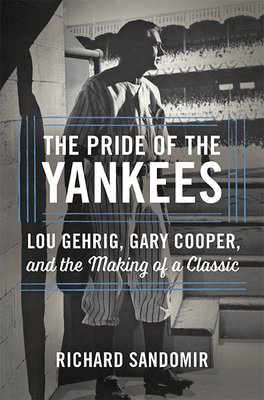

The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic (Hachette Books; hardcover; $27; 293 pages) by Richard Sandomir is interesting, insightful and revealing. Sandomir, an obituary writer for the New York Times, wrote about sports media and business for 25 years. In this book, Sandomir analyzes the reluctance of a studio mogul (Samuel Goldwyn), the persistence of Gehrig’s widow, the search to cast the right people, and the impact the movie still has today. One of the movie’s goals, Sandomir writes, was to “idealize baseball” through its “worshipful treatment” of Gehrig.

The goal was achieved, but there were some hurdles. The movie was “produced by a man, Goldwyn, who knew nothing about baseball, starring a man, Cooper, who had never played baseball, and shot by a cinematographer, Rudolph Mate, who was also new to baseball,” Sandomir writes. Still, this combination would portray baseball as “a bright and shining sport.”

Cooper, who won an Academy Award in 1942 for his lead role in Sergeant York, was not built like Gehrig, did not sound like him, and definitely did not have the Iron Horse’s baseball skills. Teresa Wright, who would play Gehrig’s wife in the film, was the perfect, lively counterpoint to the taciturn Cooper — just as Eleanor Gehrig would be to Lou Gehrig. Both actors would be nominated for Academy Awards for their roles in Pride, although neither would win.

Gallico wrote the original screenplay and kept a running correspondence with Eleanor Gehrig through letters, which Sandomir relates in great detail. These letters really bring the story of the film to life and are a key reason why Sandomir’s book is such a compelling read. Gallico’s opinion of Gehrig can be summed up in the first chapter of his own book, where he said he called it “Lou Gehrig — An American Hero,” because “he was a hero and was totally our own.” Sandomir is less sentimental as he cuts through the hero worship and presents the business of Hollywood with smooth, effective prose.

Gehrig and his wife were married in their future apartment, several days before a formal wedding was to take place. In real life, Gehrig was concerned that his overbearing mother would try to interfere or make a scene in a Long Island setting so arranged what amounted to an elopement. In the movie, Goldwyn ridiculously places Mom and Pop Gehrig looking on benevolently as Lou and Eleanor recite their vows.

There was plenty of real-life tension between Eleanor and Christina Gehrig, but as Sandomir writes, that angle was softened somewhat. As Sandomir notes, “Eleanor’s harshest comments to Gallico about Mom (Gehrig) never found their way near the film.” The romantic tone that Goldwyn wanted to set would never allow for Eleanor’s “characterizations of Gehrig family dysfunction.”

The day Gehrig ended his consecutive game streak of 2,130 games also was misrepresented. Gehrig actually took himself out of the starting lineup before the May 2, 1939, game at Detroit. But telling manager Joe McCarthy hours before the game was “not dramatic,” so the film deviates, with Gehrig informing his manager to replace him after the sixth inning with Babe Dahlgren.

“It works dramatically,” Sandomir writes, “but squelches what really happened that day.”

Among the interesting nuggets that Sandomir sprinkles throughout the book is how Dahlgren negotiated himself out of the film because of his high salary demands.

One actor who did play himself was Babe Ruth, much to the consternation of Gehrig’s wife. Ruth lost nearly 50 pounds to appear in the film, but Eleanor Gehrig believed with “some rancor” that the Bambino, who overshadowed Lou Gehrig through much of his career, would try to be a scene-stealer in Pride. But Ruth’s name would lure paying customers. “It was impossible and impractical to keep Ruth out,” Sandomir writes. Still, Eleanor Gehrig knew that Lou had suspicions that Ruth had once slept with her — a sticking point that ended the friendship between the two sluggers.

Eleanor’s emotions about the Babe were “tough and raw,” but Goldwyn prevailed. “She did not get her way, and the Pride is better for it,” Sandomir writes.

My copy of Paul Gallico's 1942 book, "Lou Gehrig: Pride of the 'Yankees'"

My copy of Paul Gallico's 1942 book, "Lou Gehrig: Pride of the 'Yankees'"

The most memorable scene in Pride, however, was Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” speech. In his book, Gallico wrote that Gehrig “was the living dead, and this was his funeral.” Gehrig’s speech, Sandomir writes “remains unmatched as a piece of athletic oratory” nearly 80 years after it was delivered and remains “a significant element of his soulful legacy.”

Goldwyn, however, had Gehrig’s immortal line — “the luckiest man on the face of the earth”— placed at the end of his speech, rather than the second sentence where it actually happened. While a full version of the speech does not exist in print (although Eleanor Gehrig claimed to help write it), it was “great one, notable for its power, structure, generosity and modesty,” Sandomir writes.

It didn’t matter that the speech was inaccurately portrayed in the film. To this day, the speech Cooper uttered in Pride is what we remember about Gehrig. He took the character of the unassuming slugger and made it his own.

“Lou seems to have become more Gary Cooper than Lou Gehrig but I suppose they had to do that, Gallico wrote to Eleanor Gehrig midway through the film’s production. “I think he still comes out a very lovely character.”

“Cooper’s last words as Gehrig were clearly his most enduring,” Sandomir writes. “Not only for their resonance over three generations, but for their uniqueness.”

Sandomir writes about Pride with no prejudice. It’s a clear-eyed look at a film classic that has left most of us misty-eyed through the years.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed