The Oakland A’s of the early 1970s blew that theory out of the water. They were the last team to win three consecutive World Series — from 1972 to 1974 — and the first since the dynastic New York Yankees did it from 1949 to 1953. En route to five straight American League West titles from 1971 to 1975, the A’s scrapped, clawed and fought with a white-hot intensity — and that was in the locker room, on airplanes and in hotels. They were just as abrasive on the field, too, and their one common bond was contempt for their penny-pinching owner.

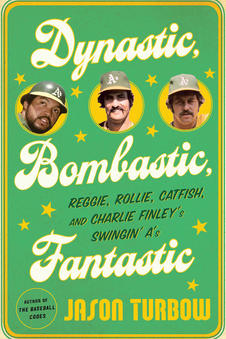

In Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish and Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $26; 386 pages), author Jason Turbow presents an absorbing, detailed and entertaining look at the dynasty that Major League Baseball probably wanted to sweep under the rug. Turbow, who wrote “The Baseball Codes: Beanballs, Sign Stealing, and Bench-Clearing Brawls: The Unwritten Rules of America's Pastime” in 2010, had plenty of material to work with as he researched the Oakland A's.

Team harmony? In October 1972, the A’s had just clinched their first World Series berth since 1931, and pitchers John “Blue Moon” Odom and Vida Blue nearly came to blows when Odom took umbrage at Blue’s insinuation that his fellow pitcher had “choked” in the series-clinching victory by not going the distance.

Odom had his share of instigation, too. On the eve of the 1974 World Series, Odom taunted reliever Rollie Fingers about his marital difficulties.

“Moon,” Fingers said, “you can’t even spell ‘divorce.’”

“Yeah,” Odom retorted, “but your wife can.”

These guys weren’t called the Swingin’ A’s for nothing.

Another time, Reggie Jackson and Billy North got into a knock-down, drag-out fight in the middle of the clubhouse, where some the A’s were playing a game of bridge. As Jackson and North rolled around the clubhouse, the game went on.

“I had a slam bid I wanted to play, and damned if people were fighting. I still played it,” Dick Green told Turbow.

Sal Bando put it all in perspective after tempers cooled. “Well, that’s it. We’re definitely going to win big tonight.”

Bando was a prophet as the A’s won 9-1, Turbow writes.

Turbow structured the book in three parts: Ascendance, covering the period from 1961 to 1971; Pinnacle, the World Series championship years of 1972 through ’74; and Descent, chronicling the team’s decline from 1975 to 1980.

Turbow interviewed players, coaches, broadcasters, sportswriters and front-office workers. He visited the homes of Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace and North, visited Mike Epstein’s baseball camp, and interviewed Green in the cafeteria at the Mount Rushmore historic site. The only key members he did not interview were Jim “Catfish” Hunter, manager Dick Williams and owner Charlie O. Finley, who had died by the time Turbow began his research. Alvin Dark, who succeeded Williams as manager, died in 2014.

In a book full of mavericks and antiheroes, Finley was the biggest of them all. So big, that Turbow mostly refers to him as “the Owner” in most of his narrative. Finley was a rags-to-riches story, a businessman who struck it rich in the insurance business. After several failed attempts to buy major-league teams, Finley bought the Athletics in 1961. He spruced up the ballpark in Kansas City, where the Athletics had moved from Philadelphia after the 1954 season. A one-man scouting team and his own general manager, Finley scoured the country for baseball talent. By the late 1960s that talent was beginning to gel with players like Hunter, Fingers, Jackson and Bando, and Finley moved the A’s west to Oakland for the 1968 season.

Turbow notes that Finley’s legacy was one of “pure duality.” He was a baseball visionary, “a perpetual mover or whom rest was never an option.” But he also was a narcissist and a self-promoter; Finley not only ran the show, he wanted to be the show. He cut a figure, Turbow writes “somewhere between tyrant and punch line.” Finley rarely got good press, Turbow writes, because he rarely deserved it.

And the owner (as opposed to Owner) was cheap. There were no programs for Game 1 of the 1973 World Series in Oakland because Finley was slow to pay the printing costs. He sold tickets in the center field bleachers at the Oakland Coliseum, hindering the hitters’ sight lines — but 5,000 tickets went unsold in the upper deck. Turbow quotes Rudi saying that Finley did not hire enough people to answer ticket requests. “There were thousands of checks sitting there for people wanting tickets for the World Series, which were not filled,” Rudi said. “Finley was just too cheap.”

After passing out beautiful World Series rings to the players in 1972, Finley went cheap in ’73, as the new rings did not feature a diamond but instead had green glass, Turbow writes.

Finley’s clumsy attempt to “fire” Mike Andrews after the second baseman made some costly errors in Game 2 of the 1973 World Series nearly resulted in a boycott by the A’s. It certainly convinced Williams to resign after Oakland won its second straight Series crown.

It was a microcosm, Turbow writes, of the turbulent A’s. “Angry players who felt abused, and a manager who could take no more,” he writes. “Finley acts, players react, nothing changes.”

Alvin Dark, a recycled former manager for Finley (he managed in Kansas City in 1966 and 121 games in 1967), took over in 1974. The players were slow to respect him and believed he was a Finley puppet.

“I knew Alvin Dark was a religious man,” Blue said. “But he’s worshiping the wrong God — Charlie O. Finley.”

The anecdotes Turbow spins in this book are alternately hilarious, sad, and shake-your-head amazing. “You have all heard of John the Baptist,” a visibly inebriated Finley told an audience of fans gathered at a restaurant in 1974. “John the Baptist was a winner. Well, tonight we’ve got Alvin the Baptist. Alvin the Baptist is a loser.”

Hugs all around.

And yet, the A’s continued to win. When Finley berated Dark loudly over his lack of usage of pinch-runner Herb Washington, the players began to feel sorry for their manager.

After half a decade of success the A’s were broken up, victims of free agency and Finley’s refusal to keep his star players.

Turbow’s prose is lively and entertaining, and some of the footnotes he writes are mini-chapters in their own right. Don’t skip them; some will make you laugh out loud, while others will offer a solid explanation of a particular episode.

The Swinging A’s could not exist in today’s major-league world. They were too scruffy, too loud, too opinionated and too confrontational. But they also were winners — in spite of their turmoil, and in spite of their mercurial owner.

In Dynamic, Bombastic and Fantastic, Turbow weaves a tale that bubbles and percolates on every page.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed