Bouton was a journeyman pitcher when he began taking notes in 1969, hanging on, as he wrote at the time, by his fingernails. As a knuckleball pitcher, that was the perfect analogy. Bouton won 21 had games in 1963 and 18 the following year, plus a pair of World Series games, but by 1969 he was struggling to latch on with a major league team. He would finish his career with a 62-63 record, but it was his observations as a writer that would set Bouton apart.

The furor generated by Ball Four was immense, and it solidified Bouton’s reputation as a maverick, a renegade, a darling of the late 1960s counterculture and a player-turned-author who pulled no punches. A half-century later, it all seems so tame in retrospect. Did we really care that Mickey Mantle went up to pinch-hit in a hungover haze? Of course not, since the Mick hit a home run, squinting out at the stands and muttering, “Those people don’t know how tough that really was.” But it was a big deal then. Sports heroes were portrayed as Jack Armstrong types, and Bouton tore away the curtain to reveal the reality of it all.

A biography about Bouton? Could one be written in the same spirit as Ball Four — funny, perceptive and thoughtful?

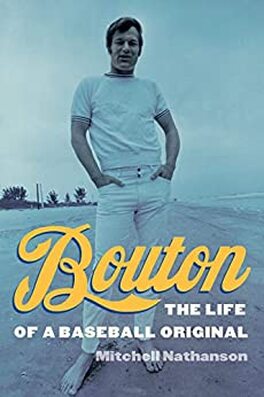

Mitchell Nathanson did so, and more. In Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $34.95 407 pages), Nathanson, a professor of law at the Villanova University School of Law, presents an honest, balanced look at Bouton, who died last July at the age of 80. The book has a May 1 release date.

Nathanson presents the humorous and inventive side of Bouton. He also reveals the self-centered, shoot-from-the-hip persona Bouton’s former roommate in Houston, Norm Miller, recognized as being similar to the knuckleball, “in that he had difficulty controlling it,” Nathanson writes.

When Nathanson broached the idea of a biography, Bouton and his wife, Paula Kurman, gave their blessing but insisted the author explore all angles of his life and waived any editorial control. Most of all, they did not want a “puff piece,” Nathanson writes.

Bouton gets high marks for his courage in writing Ball Four, his willingness to mingle with the younger generation of sportswriters — derisively nicknamed chipmunks — his fearlessness in taking political stands when baseball players mostly remained mute on the subjects of Vietnam and civil rights, his generosity with young fans and his tenacity to succeed.

That tenaciousness also gets him low marks, as Bouton insisted throughout his life that he had “to be true to myself.” If that meant not reading scores during his newscasts or antagonizing his fellow broadcasters, so be it. If it meant having extramarital affairs while his first wife, Bobbie, was at home with their three children, it was going to happen. If it meant removing the name of Leonard Shecter from the cover of Ball Four when anniversary editions of the book were released so the book looked “looked cleaner,” that was all right, too.

Shecter, a sportswriter for the New York Post and later the sports editor for Look magazine, collaborated with Bouton on Ball Four. Shecter, who died in 1974, used his editing skills and ability to push the pitcher to provide more depth and insight to set it apart from other sports books. Certainly, Jim Brosnan’s two books — The Long Season (1960) and Pennant Race (1962) — along with Jerry Kramer’s diary of the 1967 NFL season, Instant Replay, and Bill Freehan’s 1970 book, Behind the Mask, opened the door a crack for sports fans eager to get an inside look.

But Ball Four kicked the door down and was more than a “tell-some” book. Amphetamine use (they were called “greenies” back then), voyeurism and rough clubhouse humor and pranks were covered in detail. Friction between teammates, the pettiness of management and the unintentional humor imparted by Seattle Pilots manager Joe Schultz — who directed a crew of rejects and misfits — was a gold mine of material for Bouton.

In one of his few moments of hyperbole, Nathanson calls the Bouton-Shecter collaboration “the sportswriting equivalent of Lennon and McCartney.” However, Nathanson’s explanation of the writing process that shaped Ball Four could be called a hard day’s night — and more. Nathanson recounts Bouton and Shecter meeting in the sportswriter’s non-air-conditioned apartment in Manhattan to review the pitcher’s 15 cassette tapes and 978 scraps of notes, shaping them into a cohesive narrative.

“(Shecter) had a hot, sticky apartment,” Bouton told Nathanson. “And he’d say, ‘Take your pants off, Bouton. We’ve got a long night ahead of us.’”

“And there’d they be,” Nathanson writes. “Two men, in their underwear, shaping the raw material that in less than a year’s time would become Ball Four.”

Nathanson gives the reader a literary locker room view of the process that led to Ball Four. He describes how Bouton and Shecter had to fight to keep passages the publishers deemed legally sensitive. World Publishing’s lawyers targeted 42 items as “potential legal land mines.” Bouton and Shecter only acquiesced on five of them.

Nathanson also examines the argument detractors used when Ball Four was released — that it was Shecter, not Bouton, who was the writing wizard. And, that Bouton was taking notes on the sly, which is he was not. Several players are quoted in Ball Four as saying, “Hey, put that in your book.”

The note-taking did not surprise the players, then. Rather, “it was the frankness of the book that startled them,” Nathanson writes. “So much so that when asked about it, they claimed ignorance of the entire thing.”

As to the first assertion, Nathanson argues Shecter helped shape the prose but did not create it. Nathanson notes “it was Bouton’s ear for language that causes Ball Four to sing.”

Those criticisms came, if not overtly, then insinuated, by some of Shecter’s contemporaries. Of note, New York Daily News columnist Dick Young, a groundbreaking sportswriter who was the first to go into the locker room and talk to players when he covered the Brooklyn Dodgers during the 1950s, was upset by Ball Four. Young went so far as to label Bouton “a social leper,” and inadvertently gave Bouton the quote he would use to title his follow-up book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally.

It was professional jealousy. “In truth, all of Young’s bluster was cover for his pique that the man who considered himself the game’s ultimate inside was scooped,” Nathanson writes.

The Ball Four stories are enough to carry the book, but Nathanson realized there was life before and after the bestseller list. He delves into Bouton’s childhood and his early days with the New York Yankees. He interviewed the kids who began his fan club in the mid-1960s and wrote a newsletter, “All About Bouton,” and his relationship with the “chipmunk” writers.

“The Chipmunks saw Bouton as their Sinatra, their Merry Prankster,” Nathanson writes. “An increasingly rogue spirit with a singular style.”

That style bought Bouton credibility post-baseball when he became a sportscaster for WABC and, later, WCBS. Fellow sportscaster Sal Marchiano, who was constantly at odds with Bouton, told Nathanson that “he was more interested in promoting himself. That’s the bottom line, to me, about his broadcasting career. It was about him.”

Don’t just take it from an angry former colleague. Joan Walden Maurer, a professional ice skater during the 1950s who lived in the same area of New Jersey as Bouton two decades later, was equally blunt.

“Jim Bouton? Yeah, he stands in traffic and asks if anyone wants his autograph,” Maurer told me in 1979 when I visited her daughter, future CNBC Radio journalist Chris Maurer, sharpening her blades at the former athlete’s expense.

Behind the swagger and ego, there was a gentler side to Bouton, Nathanson writes. He goes into greater detail about the 4-year-old Korean boy Bouton and his first wife, Bobbie, adopted. Kyong Jo, who later Americanized his name to David, had trouble adjusting when he first entered the Bouton household, angry that his birth mother had abandoned him and disgruntled because he believed his new family did not live in America.

The child said the family would take him to America, where he would go into stores and see aisles of toys, clothes and electronics. But when the family got in the car to go home, Kyong Jo said that place “wasn’t America at all.”

Slowly, painfully, the boy adapted to American life. It’s a tender story that is rarely told about Bouton.

There was the tragic death of Bouton’s daughter, Laurie, who was involved in an automobile accident in 1997. And there was his son Michael’s op-ed to The New York Times in 1998, asking the Yankees to invite him to Old Timers Day.

Along with the brass, there was a lot of pathos, and Nathanson captures it well.

Bouton remained a tinkerer and a hustler to the end. He hit it big with former minor league teammate Rob Nelson when they developed Big League Chew, which was bubblegum in a pouch made to look like chewing tobacco. It was an immediate hit.

“He was always on the lookout for the next big thing,” Nathanson writes. “Always in search of a new and different way to bring in income and have fun while doing it.”

Bouton is bolstered by Nathanson’s research, as he used newspaper and magazine articles to provide background. He also did extensive interviews with Bouton, his two brothers, his two wives —Bobbie Bouton-Goldberg and Paula Kurman — and Jill Baer, who had an affair with Bouton.

Nathanson also talked with former teammates like Gary Bell, Tommy Davis, Larry Dierker, Norm Miller, Fritz Peterson and Mike Marshall (via email). He also spoke with sports journalists including Ira Berkow, Peter Golenbock, Keith Olbermann, Bill Shonely, Larry Merchant and Jeremy Schaap.

Bouton is a book that deserves space next to Ball Four on the bookshelf. Nathanson has done a thorough job of presenting the life of a complex man who changed the game of baseball, not by what he did on the field, but what he observed on the field, in the clubhouse and on the road.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed