From 1911 through 1917, only Walter Johnson won more games. Alexander had a 190-88 record and led the National League in strikeouts five times. Johnson, meanwhile, went 197-99 during that stretch and led the American League in strikeouts six times.

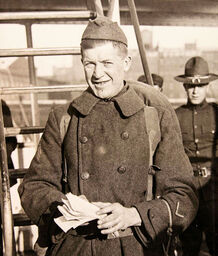

But something happened to Alexander. He went overseas to fight during World War I, serving in France as a sergeant in the 342nd Field Artillery Regiment. He effectively missed the 1918 baseball season, appearing in three games and going 2-1.

When he returned, Alexander seemed fine physically, but the war haunted him. He began drinking heavily, and his bouts with epilepsy became more of a concern but remained hidden from the public view. Alexander likely suffered from “shell shock,” which is now called post-traumatic stress disorder.

Alexander would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938 but by then his life was a haze of alcoholism. In November 1950, Alexander was found dead in a hotel room in his hometown of St. Paul, Nebraska.

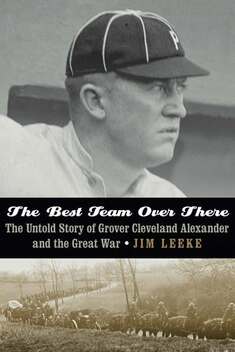

Alexander “wasn’t the relaxed discharged soldier he appeared to be,” Jim Leeke writes in his latest book, The Best Team Over There: The Untold Story of Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Great War (University of Nebraska Press; $29.95; hardback; 247 pages). “And effects of combat jangled his nerves and his psyche.”

But he was an effective pitcher and a troubled man for most of the 1920s.

Some writers believed Alexander was washed up. For example, an Aug. 18, 1921, headline in the Grenola (Kansas) Reader noted that “Alexander Nearing End of His Career.”

What many people knew about Alexander came from a rather sanitized — and at times inaccurate — portrayal by Ronald Reagan in the 1952 movie, “The Winning Team.”

Leeke helps add context and accuracy to the legend of Alexander, touching on the years before and after World War I but concentrating on the pitcher’s time in the military.

Before the war, Alexander was nearly unstoppable. He won 28 games as a rookie in 1911 and became the only other pitcher besides Christy Mathewson to win 30 or more games in three consecutive seasons. During his career he won more than 20 game nine times and tied Mathewson for the National League record in victories with 373.

“That a youth with ‘Grover Cleveland Alexander’ wished on him at birth could succeed in any line of endeavor is strange,” a June 1911 wire story began. “Most hopefuls nicked with the monacher (sic) of eminent citizens are flagged at the post.”

Not Alexander.

“He knows nothing that resembles fatigue; he never sulks; he is always ready,” a wire dispatch noted two months later.

In 1915, Alexander led the Philadelphia Phillies to their first N.L. pennant by winning 31 games, throwing 12 shutouts, completing 36 games and posting an ERA of 1.22. Alexander led the National League in innings pitched seven times and topped 300 innings nine times.

And Alexander was a favorite of fans and teammates.

“Alexander is admired, he is loved by every member of his team,” St. Louis sportswriter Sid C. Keener wrote on the eve of the 1915 World Series.

Men named their children after him. The Butte (Montana) Miner reported in September 1916 that Jerry Kennedy a popular cigar clerk a local saloon, named his 12-pound, firstborn son Grover Cleveland Alexander Kennedy. That’s a mouthful.

A wire story in March 1917, when Alexander was holding out for $15,000, noted that “his long arm reached down in the baseball depths about eight stories and pulled a team that was chronically near the tail end up to a commanding position on the heights.”

The Phillies, despite enjoying success through Alexander, traded the pitcher and catcher Bill Killefer to the Chicago Cubs two weeks before Christmas 1917, news that was “a hefty lump of coal” for Philadelphia fans.

“The deal gutted the Phillies,” Leeke writes.

It was a pre-emptive move by Philadelphia. Team officials believed Alexander would be drafted, so they took the money and ran. So, the Phillies took the money and ran. As it turned out, Alexander was drafted, despite originally believing he would receive a low classification because his mother was dependent upon him.

“The Philadelphia-Chicago deal smells little better today,” Leeke writes.

“The Great War put an end to my day dreaming of various records,” Alexander would say.

The war certainly ruined any chance of Alexander winning 400 games. He would lead the N.L. in innings pitched seven times and topped 300 innings nine times.

Leeke helps the reader understand what the men who served during World War I faced. He traces Alexander from his enlistment until he returned from Europe. Alexander received his training with the 342nd Field Artillery Regiment at Camp Funston in Kansas. The outfit was organized as “a motorized heavy-artillery outfit,” Leeke writes. Leeke draws from the regiment’s history to paint a picture of the fast-paced training Alexander and his colleagues went through.

What made this regiment stand out was its athletic talent, Leeke writes. In addition to Alexander, athletes in the regiment included Clarence Mitchell of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Otis Lambeth of the Cleveland Indians, Win Noyes of the Philadelphia Athletics and Chuck Ward of the Dodgers. Football star George “Potsy” Clark, who coach the Detroit Lions to an NFL championship in 1935, also was a member of the regiment.

In a nice touch, Leeke begins every chapter of The Best Team Over There with a war poem from famed sportswriter (and WWI Army lieutenant) Grantland Rice.

“They were surprisingly good,” Leeke told podcaster Dean Karayanis on the “History Author Show” in April. “Not what I expected. You know, some of his sport poems are very light and casual and funny. But the war poems, by and large, were not that.

“They have real emotion to them, some of them have real power to them.”

The doughboys at Camp Funston, meanwhile, were suffering through training because of the Kansas prairie’s extreme seasonal changes.

Soldiers found the camp “too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, and too unpredictable in between,” Leeke writes.

As for Alexander, he had time for a quick wartime wedding, marrying Amy “Aimee” Marie Arrant on June 1, 1918, in Manhattan, Kansas. Alexander and his outfit shipped to Camp Mills, New York, two days later and headed overseas on June 28, Leeke writes.

Leeke devotes chapters to Alexander’s unit sailing to Great Britain and then to France. The 342nd arrived in Liverpool on July 10 after what Alexander called “a splendid journey.” Four days later they arrived in France and traveled to Camp de Souge, nicknamed “The Little Sahara.” The troops had to learn how to put on gas masks immediately, and that was always a concern.

Leeke writes that Alexander was soon promoted to corporal and had at least one epileptic seizure while in France. His promotion meant that he had less time to play baseball, although “the sport was wildly popular among Yanks serving in France.” Alexander would say that he pitched in five games during his time in France.

Alexander and his unit finally saw action in the St. Mihiel offensive, digging in at Bouillonville. Alexander heard the shelling by the Germans and at one point watched a shell bounce past him; fortunately, it was a dud, Leeke writes.

Alexander would be promoted to sergeant on Oct. 3, 1918, and became a gunner. Alexander would be praised for coolness under fire, exhibiting the same calm demeanor he had on the mound, Leeke writes. War, of course, has higher stakes, so Alexander’s men would come to appreciate his steely persona.

Leeke provides plenty of detail, putting the reader into the trenches.

It is unclear when Alexander became affected by PTSD, and he never discussed it directly.

“But none could have been unaffected by the sights, smells, and sounds of war,” Leeke writes, “The awkward spread of dead animals, the terrifying whiff of gas, the deafening tom-tom-tom of the howitzers.”

No wonder “John Barleycorn had begun tightening his grip” on Alexander, who first began drinking hard liquor in France.

A decade later, Alexander “never budged” during a spring training game when some children set off fireworks in the grandstand.

“He just sat there stiff as a board, teeth clenched, fist doubled over so tight his knuckles were white,” teammate Bill Hallahan recalled.

Alexander’s unit remained in occupied Germany until early 1919, and Alexander finally returned to the United States that spring. After losing a 1-0 decision to Cincinnati on May 9, Alexander finished the year with a 16-11 record and a league-leading 1.72 ERA and nine shutouts.

Alexander always insisted he was sober when he came into Game 7 of the 1926 World Series to fan Lazzeri to save the Cardinals’ lead. The Winning Team movie used it as its final scene, but Alexander pitched two more scoreless innings, helped when Babe Ruth was caught stealing for the final out of the game.

Life was not kind to Alexander after baseball. His wife divorced him and he worked in a penny arcade and flea circus in New York’s Times Square. After making an appearance at the opening of the Hall of Fame, “the broken-down pitcher resumed his rocky road to nowhere,” Leeke writes.

In November 1940 he received treatment at a Veterans Administration hospital in the Bronx. In 1944 police found him wandering around the streets of East St. Louis, Illinois, in his pajamas at 2 a.m. In May 1949 he fractured a vertebra in his neck after falling down a flight of stairs at an Albuquerque hotel. Later that year he was admitted to a Los Angeles hospital to be treated for skin cancer.

Alexander’s final association with baseball game in 1950, when he visited Yankee Stadium for the final two games of the World Series, which featured the Phillies in the Fall Classic for the first time since Old Pete led his squad in 1915. He died several months later.

Leeke was not writing a definitive biography about Alexander. Rather, he concentrated on the pitcher's time in the military while bookending his life before and after World War I.

The research is detailed and extensive, with 24 pages of end notes and a meticulous bibliography.

Leeke’s writing is straightforward and clear, and his narrative is entertaining.

The Best Team Over There is a fine work of sports and military history. It gives the reader some new perspective about players who went overseas to fight during World War I, and perhaps answers some questions about why Alexander could not escape his demons after returning.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed