That may seem like an odd comparison, but read the collaborative efforts of Spatz and Steinberg. Their prose sings.

Their latest effort is perhaps their most challenging project together, but one both baseball historians tackled with relish to produce a very interesting narrative.

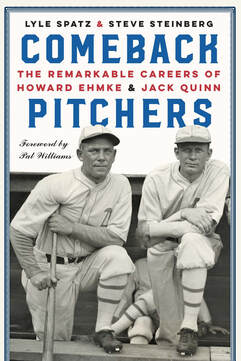

Comeback Pitcher: The Remarkable Careers of Howard Ehmke and Jack Quinn (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 473 pages) is a look at two pitchers whose careers spanned the deadball and lively ball eras of the 1910s and 1920s.

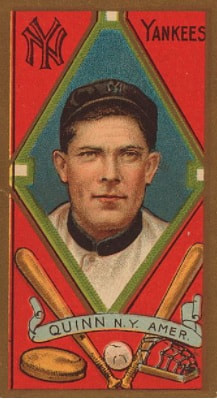

Neither are really household names, which is interesting when one considers that Quinn won 247 games during his 23-year major league career — including a two-year stint in the Federal League. Ehmke pitched 15 seasons in the majors and had a 166-166 record.

The authors note in the book’s preface that many major leaguers “are not headliners but rather men who contribute to their teams’ success while occasionally flirting with stardom.”

That captures Ehmke and Quinn perfectly.

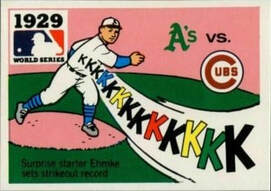

Ehmke confounded the experts when he struck out a record 13 hitters as a surprise starter in Game 1 of the 1929 World Series. Quinn held the record of being the oldest pitcher to win a game, a mark that stood for nearly 80 years.

Quinn was 49 years, 70 days old when, pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers on Sept. 13, 1932, he went five innings in relief to pick up 6-5 victory in the first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals. Jamie Moyer was 49 years, 141 days old on April 17, 2012 when he went seven innings as a starter for the Colorado Rockies and beat the San Diego Padres 5-3.

That is, we think that is how old Quinn was. He was one of the last legal spitball pitchers before his career ended in 1933 with the Cincinnati Reds, and during his playing days he was coy about his origins — or perhaps, he simply didn’t know.

The authors title their first chapter, “Jack Quinn, Man of Mystery,” and it is easy to see why.

It took a family relative by marriage, after a decade of genealogical research, to finally nail down Quinn’s birthdate of July 1, 1883, in the Slovakian town of Stefurov, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The relative, Mike Scott, concluded that Quinn never told his age because “he never knew.” Quinn’s mother died shortly after the family moved to the United States, and his father worked long hours in the Pennsylvania coal mines.

John Picus Quinn’s middle name was an Americanization of his father’s surname, Pajkos. The authors note that Quinn changed his last name to Quinn because there were very few Eastern European baseball players, and prejudices ran high. “Quinn” sounded like an Irish name, and baseball had plenty of Irishmen at the turn of the 20th century.

Spatz and Steinberg are award-winning writers who have collaborated on two previous books: “1921: The Yankees, the Giants and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York” in 2010, and 2015’s “The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees.”

Separately, Spatz has written several books, including 2011’s Dixie Walker: A Life in Baseball, Hugh Casey: The Triumphs and Tragedies of a Brooklyn Dodger, in 2017, and New York Yankees Openers: An Opening Day History of Baseball’s Most Famous Team, 1903-2017.

Steinberg’s body of solo work includes Urban Shocker: Silent Hero of Baseball’s Golden Age in 2017, and The World Series in the Deadball Era in 2018.

Their partnership is a smooth one, with “a true collaboration” bringing out the best in every subject they research. It is not a choppy book, where one writer’s style stands out so it is easy to determine which author wrote a particular chapter. Other than a few overlaps here and there, it is a seamless work.

“As with a personal relationship, when it works well, it is rewarding and enriching,” Steinberg told SABR writer Bill Lamb in an interview. “But it takes more effort than a solo project.”

Speaking of partnerships, Quinn and Ehmke were teammates for several years. Both played for the Boston Red Sox from 1923 through 1926, and for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1926 to 1930.

“I was as strong as an ox … and could throw pretty smart,” Quinn once said.

Having a spitball in his arsenal helped, too. Quinn kept defying the odds, even when newspaper accounts noted that there were “plenty of folks in New York willing to testify that Quinn is through as a top-notcher.

Quinn had the last laugh. He was durable and still pitching in semipro leagues into his 50s.

Ehmke, meanwhile, also won at least 10 games 10 times during his career. He had a baffling array of pitches and windups, including a submarine delivery that seemed to come from the ground. Ehmke could also throw sidearm and overhand. He won 20 games in 1923 for a Red Sox team that only had 61 victories and followed it up with 19 in 1924 for a seventh-place Boston squad that won just 67 times.

Ehmke was hailed as “the next Walter Johnson” when he played for the Detroit Tigers in 1916. Ehmke pitched six seasons in Detroit, but the friction between him and Ty Cobb in 1921 and 1922, when the Georgia Peach was the Tigers’ manager, is intriguing.

Before Cobb became manager in 1921, Ehmke made it known that he wanted to be traded. “He and Cobb had not had an open breach in 1920, but both thought it best they stay apart,” the authors write.

Cobb would later refer to Ehmke as “indifferent,” and intimated that he lacked courage, while the pitcher called his manager “Detroit’s greatest pennant handicap.”

When Ehmke was traded to Boston and faced the Tigers in May 1923, he hit three batters, including Cobb. When Ehmke went under the stands after the game, Cobb was waiting for him, the authors write. Cobb won the fight, but Ehmke said he had more satisfaction from winning the game.

“I’d still rather be the winning pitcher than the winner of the fight,” he said.

Both Ehmke and Quinn found a home in Philadelphia, just as Connie Mack was returning the Athletics to prominence.

The authors write that during most of the 1929 season several of Philadelphia’s top players “had little use” for the Ehmke, including Al Simmons, who reportedly exchanged punches with the pitcher.

But Ehmke was 35 and wanted to pitch in a World Series, and Mack sent him to scout the Cubs during the final month of the season. That was no secret; the stunner was that Ehmke would start the series opener.

“The thought was that Ehmke was scouting the Cubs for the benefit of Mack and the A’s players,” the authors write. “Little did they realize he was scouting them for himself.”

The Cubs were primarily fastball hitters, and Ehmke’s “lazy motion and slow stuff” tripped them up.

Award-winning #SABR authors Steve Steinberg & Lyle Spatz offer some insights into their baseball research process: https://t.co/XDwpHPDohv pic.twitter.com/LXyIjQdgAp

— SABR (@sabr) November 23, 2016

“Ehmke had risen above the criticism and injuries he had endured those sixteen years to pitch the game of his life,” the authors write, noting that his 13 strikeouts topped the World Series record set in 1906 by Ed Walsh.

When Carl Erskine struck out 14 Yankees in Game 3 of the 1953 World Series, Ehmke sent the Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher a congratulatory telegram, the authors write.

Erskine had no idea he had set a record and did not know who had held it.

“I’m still not sure that I can even spell that fellow’s name right,” Erskine told reporters.

Ehmke would be released in May 1930. He later went on to have a successful business career producing sports tarpaulins for outdoor sports events. He remained close to Connie Mack and Philadelphia baseball events, attending old-timers’ games. He also was an enthusiastic golfer who shot in the low 80s, playing in tournaments up until a week before his death in 1959.

At 46, Quinn became the oldest pitcher to start World Series game when he opened at Shibe Park in Game 4. However, he was trailing 6-0 when he left the game after facing four batters in the sixth.

Fortunately for Quinn, that effort is hardly remembered, because the Athletics pulled off the biggest comeback in World Series history, scoring 10 runs in the seventh inning to win 10-8 and take a 3-1 lead in the Fall Classic.

The following year Quinn became the oldest player to appear in a World Series game, pitching the final two innings of Game 3 in a 5-0 loss. He was released after the Series and was picked up by the Dodgers, where he led the National League in saves in with 13 in 1931 and nine in 1932. He got into 14 games with the Reds in 1933 before he was released, pitching his final game a week after he turned 50.

While Ehmke had a comfortable retirement, Quinn scrambled to stay in baseball, pitching for semipro teams and even managing the House of David squad. However, his world was ripped apart in July 1940 when his wife Georgiana (known as Gene) tripped on a sprinkler and fell over a park bench during a family gathering. Her leg injury led to gangrene and she died two days later.

“It was a blow from which he would not recover,” the authors write.

Quinn began drinking heavily and died in 1946 from cirrhosis of the liver.

“He drank his sorrow — to death,” a family friend said.

Comeback Pitchers might be a niche read, but it is a fascinating look at two pitchers who made their mark, particularly during the free-swinging 1920s. Spatz and Steinberg lift both pitchers out of the haze and obscurity and show them for what they were — very good pitchers in an era that focused on hitters.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed