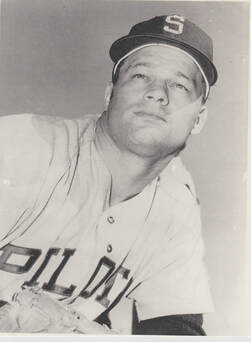

I went back and reread that entry after learning that Bouton had died Wednesday at his Massachusetts home at the age of 80.

The prank the Pilots played on Talbot, where he got a letter from a fan promising $5,000 after the fan won a contest, was hilarious, and so was Bouton’s narrative.

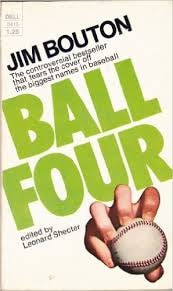

It was the kind of insider stuff that, as a 13-year-old in 1970, I craved to read about. Baseball players were my heroes, but it was fun to learn these guys weren’t saints. Ball Four showed the locker room as it really was, with young men who not only were talented athletes, but also drinkers, pill poppers and skirt chasers. Players could be mean, crude, profane, tough or silly. They could play cruel jokes, kiss each other on the lips, yell lewd things to women while riding on the team bus and grumble about their lack of playing time.

Managers and coaches could be distant or simply out of touch.

Those players and coaches also could be thoughtful, political and intelligent.

Bouton was a decent pitcher for the New York Yankees, but it was his keen eye for detail and his groundbreaking book, Ball Four, that made him a baseball legend. Certainly, the baseball establishment did not take too kindly to Bouton’s revelations — in fact, he was vilified and shunned by players and raked across the coals by sportswriters.

New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote that Bouton was a “social leper,” and unwittingly gave the budding author the title for his second book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally. Much of the invective leveled at Bouton came because he violated the unwritten code of the baseball clubhouse, an athletic sort of omerta: “What you see here, what you hear here, what happens here, stays here.”

Looking back, here’s what I think. I believe many of the writers who followed the teams even into the 1960s had an agreement — unwritten or otherwise — to keep personal items out of the newspapers. How else to explain how many of Babe Ruth’s indiscretions never became public — and he was no saint, by any means.

There had been some sportswriters emerging in the 1960s — Leonard Shecter, who helped Bouton write Ball Four, was one — who was part of the new breed of sports journalists referred to as chipmunks, because of their incessant chattering and pointed questions. These younger writers dug deeper and asked tougher questions.

When Bouton wrote Ball Four, suddenly all bets were off — and the old guard of sportswriters was forced to become reporters and journalists.

Never mind that Bouton, nicknamed the Bulldog early in his career, won 21 games in 1963 and a pair of World Series games in 1964 after winning 18 games that season. He was persona non grata in the eyes of the baseball establishment after writing Ball Four.

I was always surprised by Dick Young’s reaction to the book since he was the prototype of the sportswriter who went into the locker rooms and asked questions without dewy-eyed awe. His work during the 1940s and ’50s with the Daily News was the gold standard for future beat reporters.

So why the animosity? Who knows — maybe Young wanted to write the “tell-all” book about baseball, and Bouton beat him to the punch.

Ball Four was inspired to a degree by another pitcher’s diary — The Long Season, published in 1960 by Jim Brosnan. While Brosnan kept the locker room details to a minimum, Bouton used a no-holds-barred approach.

Even though I own the hardback version of Ball Four with all of its updates, I still have the dog-eared paperback I read as a kid.

Even though I own the hardback version of Ball Four with all of its updates, I still have the dog-eared paperback I read as a kid. Some of the portraits he painted were tremendous. Pilots manager Joe Schultz, who would tell his players to go out and win “and pound that Budweiser” after the game. Or Gary Bell, whose response at a pregame meeting about every opposing hitter was “Smoke ’em inside.”

"Gary Bell is a beautiful man," Bouton wrote.

Younger players like Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall were blossoming into men who would not follow the old guard blindly.

And what lines. Hovley came up to Bouton in spring training and told him that “to a pitcher a base hit is the perfect example of negative feedback.”

The talk about “greenies” — amphetamines — was prevalent throughout the book. At one point, Bouton asked teammate Don Mincher how prevalent greenies were. Did half of the player take them? More than that?

“Hell, a lot more than half,” Mincher said. “Just about the whole Baltimore team takes them. Most of the Tigers. Most of the guys on this club. And that’s what I know for sure.”

The biggest controversy that came out of Ball Four was Bouton’s portrayal of his former teammate, Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle. Mantle’s retirement in March 1969 sparked memories from Bouton — some good, others that were revelations to many fans.

“On the one hand I really liked his sense of humor and his boyishness,” Bouton wrote. “… On the other hand there were all those times when he’d push little kids aside when they wanted his autograph.”

It was only a few pages of memories, but it caused anger among players and fan who were not used to seeing their heroes, warts and all. Mantle was my favorite player when I was growing up, but Bouton’s revelations did not offend me in the least. It made The Mick more human, in my view.

Read The Last Boy by award-winning author Jane Leavy. There is more detail in that book about Mantle — good and bad — than Bouton ever published in Ball Four. Leavy also gives Babe Ruth the same no-holds-barred treatment in her latest book, The Big Fella.

Bouton turned out to be a better author than a pitcher, and baseball never really forgave him for breaking the code of silence. He reconciled with Mickey Mantle before the slugger’s death in 1995, and the Yankees invited him to an Old Timer’s Game in 1988 after his son, Michael, wrote an editorial in The New York Times on Father’s Day that year, telling the team to let bygones be bygones.

The cruelest fate for Bouton is that a man of his wit and intelligence was felled by dementia. He suffered a stroke in 2012 and was plagued by a brain disease that was discovered in 2017.

One of baseball’s great voices has been silenced, but Bouton’s legacy lives on through Ball Four. His love for the game was deep, as he wrote in the final paragraph of that 1970 bestseller.

"You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time," he wrote.

RIP, Jim Bouton. Your final pitch was a strike, and the baseball establishment whiffed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed