Hall of Famers are normally famous for their achievements. Tony Lazzeri had a stellar 14-year career, played on six American League pennant winners and five World Series champions. He drove in 100 or more runs seven times, had a career .292 batting average, and had double-digit numbers in home runs in 10 seasons despite batting in the lower third of the order.

And yet, for many years, Lazzeri was noted for his biggest failure — striking out in a key situation during Game 7 of the 1926 World Series. Grover Cleveland Alexander, who struck out Lazzeri that day, has a notation on his Hall of Fame plaque from 1938 that states the pitcher “won 1926 World Championship for Cardinals by striking out Lazzeri with bases full in final crisis at Yankee Stadium.”

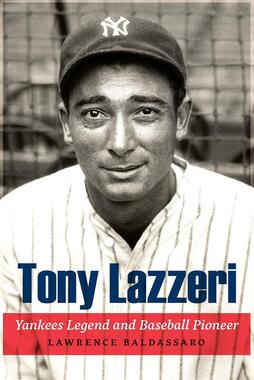

As Lawrence Baldassaro writes in his incisive biography about the Yankees’ second baseman, Lazzeri was “relegated to the dustbin of baseball history.”

Not anymore.

In Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer (University of Nebraska Press; $34.95; hardback; 314 pages), Baldassaro highlights the career of a player who was overlooked but played a key role as a baseball pioneer. A decade before Joe DiMaggio broke into the game, Lazzeri was the first truly big Italian American baseball star. Sure, there was Ping Bodie (born Francesco Stefano Pezzolo), who played from 1911 to 1921, but Richard Ben Cramer described Bodie as “slow of everything but mouth.” In the National League, Babe Pinelli played in the National League from 1922 to 1927 but would have more lasting fame as a major league umpire.

Baldassaro provides a deeply researched chronicle of Lazzeri’s baseball career, and also shines a light onto Lazzeri’s personal life, including his battle with epilepsy.

The most interesting revelations in Tony Lazzeri are the blatant ethnic slurs he endured — a lot of it coming from sportswriters who believed they were adding colorful adjectives to a story.

But, be honest — what player of Italian heritage would want to be known as the “Walloping Wop,” as one writer wrote in an otherwise glowing description.

Baldassaro is a professor emeritus of Italian at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. He has written Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball (2011); Baseball Italian Style: Great Stories Told by Italian American Major Leaguers from Crosetti to Piazza (2018); and The Ted Williams Reader in 1991. A native of Chicopee, Massachusetts, Baldassaro watched his first major league game in 1954, when he attended an exhibition game between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Giants.

Although a pitcher as a youth, Baldassaro notes that a favorite glove bought for him by his father was a Yogi Berra catcher’s mitt.

In Tony Lazzeri, Baldassaro provides a nuanced view of Italian Americans — on and off the baseball diamond.

Some of those sportswriters’ descriptions may have been rooted in how Americans perceived Italian immigrants during the first three decades of the 20th century. This is the most fascinating part of Baldassaro’s narrative. Mistrust had been fueled for decades, Baldassaro writes, with even The New York Times depicting Italian immigrants as prone to crime and violence.

In 1926, Lazzeri’s rookie season with the Yankees, the most public figures of Italian descent were gangster Al Capone and anarchists Niccolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Baldassaro notes.

Lazzeri was overshadowed during his career by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and DiMaggio, but “Poosh-Em-Up Tony” was a steady force on those Yankees’ pennant winners. He was not a nationwide sensation like Ruth — even though he became the first professional baseball player to hit 60 home runs in a season (in 197 games with Salt Lake City during 1925) — but Lazzeri was popular with the Italian populations of every stop in the American League.

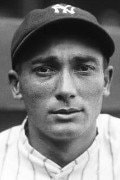

In Luckiest Man, Jonathan Eig described Lazzeri as “a tall, skinny kid, with big ears, a prominent nose, and cheekbones that looked as if they might poke through his flesh.” Baldassaro adds the impressions of sportswriters of the 1920s, who described Lazzeri as “swarthy,” “olive-skinned,” with high cheekbones and “smoldering eyes.”

Lazzeri was accepted as a baseball player, but many writers could not exist stirring their stories with strong ethnic undertones, reminding readers that “he was not quite one of us.”

“He remained, essentially, equal but separate, sometimes on the fringes of mainstream American culture,” Baldassaro writes.

Dialect headlines describing Lazzeri’s baseball ability began in The Salt Lake Tribune in 1925, intended as terms of endearment but laughable and insulting today. After hitting his 58th home run that year, Baldassaro writes, the Tribune headline read, “Our Tone, She Poosh Um Oop Two Time, Maka da Feefty-eight.”

Other than the ethnic angle, Lazzeri usually received just passing mention by authors writing about the Yankees of the 1920s and ’30s.

Paul Gallico wrote in 1942’s Lou Gehrig: Pride of the “Yankees” that Lazzeri “was no slouch with his funny sliding swing that could park a ball into the bleachers.”

Charlie Gentile noted in 2014’s The 1928 New York Yankees that Lazzeri was “considered by many” to be the best second baseman in baseball and worth “at least $150,000” to other teams. Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz quoted Miller Huggins praising Lazzeri in their 2015 work, The Colonel and Hug. The Yankees manager declared that players like Lazzeri “come around once in a generation” and called him “a dead game guy and a terrific competitor.”

Baldassaro notes that while Lazzeri’s work on the field was public, there was plenty of mystery about his private life. Even something as innocuous as Lazzeri’s middle name was open for debate. It could have been Michael, Marco or even Mark. Baseball-Reference.com lists it as Michael, and so does the Society for American Baseball Research. However, Lazzeri’s father filed an affidavit to Canadian authorities when Lazzeri was about to take a job managing the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1940, Baldassaro writes, and the middle name was listed as “Marco.” Other legal documents also support Marco or Mark, but even Lazzeri’s descendants are unsure.

Other fuzzy details Baldassaro attempts to sharpen include where Lazzeri grew up in San Francisco, and his marriage to Maye Janes — when Lazzeri proposed, he told Maye that he would not leave to play ball in Peoria unless she accompanied him.

“I wasn’t sure he loved me, but I knew Tony loved baseball,” Maye Lazzeri said in a 1989 interview. I couldn’t believe he was ready to give up baseball for me.”

Later, Baldassaro explores the time Lazzeri filed for divorce in December 1936 on the grounds of cruelty. A day later, the couple reconciled, and there was no mention of it again.

“It’s as if this brief drama … immediately disappeared into a black hole, leaving behind no evidence of the issues that led Lazzeri to seek a divorce,” Baldassaro writes.

Baldassaro also visits Lazzeri’s contract squabbles with the Yankees. He had a minor tiff with general manager Edward Barrow in 1930 but came to terms quickly. After Lazzeri had a dismal season in 1931, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert speculated that his player was distracted by heavy losses in the stock market.

Baldassaro disputes that notion, noting that Lazzeri and his wife bought a six-room house in 1932. If they had lost so much money, “would they have been able to recoup enough of their losses in the height of the Depression to enable them to make such a purchase?” he writes.

The author speculates that injury — or perhaps increased episodes with epilepsy — might have been the cause for Lazzeri’s struggles. If Lazzeri’s medication dosage was increased during that time, for example, his reflexes could have been impacted.

While Baldassaro is unable to prove the epilepsy theory, it is certainly plausible.

Lazzeri’s health issues led to trade rumors during the early 1930s, but the Yankees never made the deal. Good thing, too. Lazzeri’s greatest game came in May 1936, when, batting eighth, he hit a pair of grand slams, a solo homer and a triple and drove in 11 runs. The day before, Lazzeri hit three homers during a doubleheader. His six home runs in three consecutive games set a major league record that stood until 2002, when Shawn Green had seven, Baldassaro writes.

Baldassaro’s research is excellent. His bibliography includes 68 books, articles and papers, and there are 19 pages of end notes that reference newspaper articles, census records and scrapbooks from the Lazzeri family. The only major glitches came when Baldassaro mistakenly mixed up Lefty Gomez with Lefty Grove (page 182), and calling the St. Petersburg Times the Tampa Bay Times (a title they did not adopt until 2012) in a 1934 article (also page 182).

Those are minor blemishes. The biggest blemish on Lazzeri’s career — the strikeout against Alexander in 1926 — was washed away when he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

Tony Lazzeri helps the reader get beneath the surface of those great Yankees teams of the 1920s and 1930s. Lazzeri was a driving force on offense, played strong defense and provided leadership and other intangibles that were crucial to the team’s success. Baldassaro also weaves in the ethnic attitudes of the day, asserting that while Lazzeri was not the first Italian American baseball player, his success helped open the door for others.

Baldassaro’s work cuts across baseball, history and social channels, and is an enriching read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed