Taking a knee had a more religious tone 50 years ago. That’s because the Mets winning the World Series was nothing short of a miracle. The ragtag franchise, which debuted in 1962 with 120 losses and had never finished better than ninth place in the National League, was on top of the baseball world.

“Good memories,” Tom Seaver tells Bud Harrelson when some of the Mets gathered to meet the pitcher and swap stories in 2017.

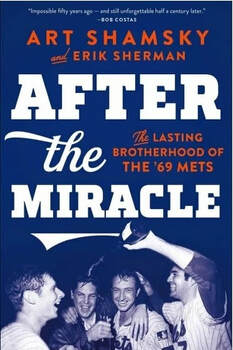

There are plenty of good memories in After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the ’69 Mets (Simon & Schuster; hardback; $28; 325 pages), but the book, written by former major leaguer Art Shamsky and author Erik Sherman, is alternately happy and sad. The book takes on added poignancy now in the wake of Seaver’s dementia, announced March 7 by the Hall of Fame pitcher’s family.

The book begins with Shamsky organizing a mini-reunion of some of the 1969 Mets, including himself, Harrelson, Jerry Koosman and Ron Swoboda. The foursome traveled to California in May 2017 to meet with Seaver, who had been suffering from Lyme disease since 1991.

What happens in between the first and final chapters is magical, as Shamsky, Harrelson, Koosman and Swoboda piece together the Mets’ 100-62 regular season, their three-game sweep of the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS, and their shocking World Series victory against a Baltimore Orioles team that won 109 games during the regular season and swept to victory in the ALCS.

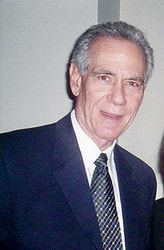

Art Shamsky played four seasons for the Mets, including the 1969 season.

Art Shamsky played four seasons for the Mets, including the 1969 season.

While both players chafed in their part-time roles, they accepted them, especially since Mets manager Gil Hodges was not going to budge.

“We knew who the boss was, didn’t we?” Seaver asked his former teammates.

It was Hodges, the first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers of the late 1940s and 1950s who regrettably has not been elected to the Hall of Fame.

After baseball, Shamsky worked in New York as a sportscaster and later joined ESPN. In 2004, he wrote The Magnificent Seasons: How the Mets, Jets and Knicks Made Sports History and Uplifted a City and the Country.

Sherman, meanwhile, has written a book about the 1986 Mets (Kings of Queens) and co-authored autobiographies with Johnson, Glenn Burke, Steve Blass and Mookie Wilson.

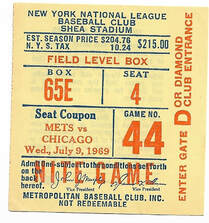

Tom Seaver game within two outs of pitching a perfect game on July 9, 1969.

Tom Seaver game within two outs of pitching a perfect game on July 9, 1969.

The Mets trailed the Chicago Cubs by nine games in the NL East by Memorial Day, but then ripped off an 11-game winning streak in June and early in the season.

Seaver pitched a near-perfect game against the Cubs on July 9, allowing a single in the ninth inning to rookie Jimmy Qualls, and the acquisition of Donn Clendenon put some more pop into the Mets’ lineup.

“Clink,” as Clendenon was called, liked to have himself paged every five minutes “just to hear his name.” His direct opposite, third baseman Ed Charles, was the team’s oldest player, read poetry and was nicknamed “the Glider." Anyone who saw Charles dance in the infield after the final out of the 1969 World Series would be hard-pressed to argue.

The Mets finally caught the Cubs in September, rolling past a talented but obviously frazzled squad worn out by the divisional race and the tense clubhouse atmosphere created by Chicago manager Leo Durocher.

That free spirit kept the Mets loose, and that’s what Shamsky said he misses most. Swoboda, a “flower child,” argued politics with ultraconservative pitcher Don Cardwell. Pitcher Ron Taylor sat on the clubhouse floor “reading Socrates or some medical journal.” Catcher Jerry Grote was avoided for his grumpiness, while ebullient young reliever Tug McGraw was liable to say or do anything.

“It’s the friendships, the camaraderie, the characters, the freedom to say anything you wanted, and the ability to deal with adversity in whatever way worked best for you where I feel the greatest void,” Shamsky writes.

The book also sheds some light on the game when Hodges walked out to left field to remove Jones from a July 30 contest against the Houston Astros. The players still speak with reverence of Hodges, who died during spring training in April 1972, two days shy of his 48th birthday.

When Shamsky and his teammates met Seaver at his California home, the memories flowed like the wine the former pitcher bottled from his vineyards. They argued whether Game 2 or Game 3 of the World Series was more pivotal for the Mets and needled one another like all ballplayers do. Sherman does his part, asking questions and making statements that acted as effective prompts for the aging players.

But the emotions crest when Seaver asks Shamsky, “how the hell did I get to be seventy-two years old? How did that happen to us, Art?”

It happens to all of us, but as Shamsky writes, the memories of what the Mets did in 1969 will never fade.

“We were the closest teammates during the best of times,” Shamsky writes.

Fifty years. It seems like only yesterday that the Amazin’ Mets were kings of baseball. In After the Miracle, the reader goes down memory lane with some of the men who made that season amazing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed