The baseball community should be grateful.

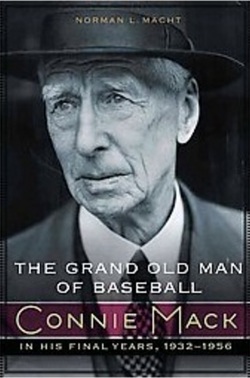

Macht, a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, turned 86 on August 4. He ends his biography of Mack with a flourish, with “The Grand Old Man of Baseball: Connie Mack in His Final Years, 1932-1956” (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $39.95; 624 pages).

This finale follows Volume 2 — “Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915-1931” — which was released in 2012 and spanned 720 pages. The first book — “Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball” — was 742 pages and was published in 2007.

Macht conducted interviews, and researched newspapers from Philadelphia, Washington, New York, Chicago, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He also interviewed Connie Mack’s children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews.

“The Grand Old Man of Baseball” covers the final 24 years of Mack’s life, when the Great Depression forced him to break up the team that had dominated the American League from 1929 to 1931.

Baseball readers have been conditioned through the years by articles such as “Mr. Mack,” written by Bob Considine in the August 9, 1948, edition of Life magazine. It was a warmly written feature that referred to Mack as “the Mr. Chips of baseball,” delighting fans with his gentle whimsy.

Mack himself massaged the legend with his 1950 book, “My 66 Years in The Big Leagues.”

Macht debunks some of those myths about Mack. For all of his courtliness, Mack had a temper and was not averse to swearing on occasion. He was not always a favorite of umpires, either, having his son Earle go out and bring them to the dugout to discuss a call.

“Mr. Mack was a nice gentleman,” umpire Ernie Stewart said, “but he was not the saint that everyone has painted him to be.”

And despite his reputation as a skinflint, Mack could be generous at times, writing checks to players during the season for outstanding performances. Or, just to be kind.

Tom Ferrick was the Athletics’ top reliever in 1941, going 8-10 with seven saves and a 3.44 ERA. Placed on waivers after the season, Ferrick was claimed by Cleveland.

Later that fall, Mack asked Ferrick to meet him at his office.

“‘Young man,’ he said to me, ‘when we signed you we didn’t give you any money. We made $7,500 from Cleveland for you. I want to give you something for yourself.’”

Mack handed Ferrick a check for $1,000.

“He didn’t have to do that,” Ferrick recalled.

To be sure, Mack was a tough negotiator at contract time, and economics prevented him from paying high salaries. He was up front about it with his players, and many seemed content to receive a slight bump in pay as opposed to nothing at all. After all, baseball player salaries were higher than the general worker made.

Macht details some of the reasons why Mack missed parts of some seasons. In 1937, for example, he missed the last 34 games of the season due to a “stomach disorder,” which could have been a gall bladder attack. That condition flared up again in 1939, limiting Mack to only 62 games in the dugout. Many observers, including Mack himself, believed this second condition would prove fatal — but once again, Mack rebounded and would manage for another decade, saying that “the doctor says I’m good for many more years.”

But Mack’s workload, enormous even for a younger man, would take its toll.

“Connie Mack was either selectively deaf or acutely stubborn,” Macht writes. “His body was yelling at him to quit trying to do the work of four men.

“But it was speaking a foreign language.”

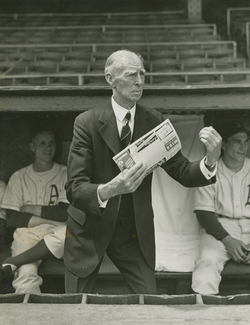

Connie Mack managed the Athletics until he was nearly 88 years old.

Connie Mack managed the Athletics until he was nearly 88 years old. Macht also outlines the marital difficulties between Mack and his second wife, Katherine. At times, the couple lived apart, and after Mack’s death, Katherine took a photo of her husband and thrusted it at their son, Connie Jr.

“Take that out of here,” she said.

One of the more fascinating parts of this book was the sale of the Athletics to Arnold Johnson and the eventual shifting of the franchise west to Kansas City. Macht provides rich detail about the inner workings of the deal, and how Mack’s oldest sons — Roy and Earle — argued and feuded among themselves. But they were in alignment against their younger half-brother, Connie Jr.

“Roy and Earle, though having little use for each other, were allied against Connie Jr., the only one with any rapport with the players and the Shibe Park employees,” Macht writes. “He had more ideas in a week than Roy or Earle had had in thirty years.”

The chapter titled: “The Sale of the A’s: A Mystery in Four Acts” is a blow-by-blow description of backroom meetings, double-crosses and fraternal sniping.

“Neither Roy nor Earle had been honest and aboveboard in everything each had said and done,” Macht writes. “Their public statements seemed to reflect more of a priority to be contrary to each other than to honor their father’s wishes or the fans’ interests.”

Macht’s research is outstanding, although a few minor points emerge. He refers to Jimmie Foxx as “Jimmy” throughout the book, a curious deviation coming from a man who in 1991 wrote a book called “Jimmie Foxx” from the Baseball Legends series. Although, to be fair, Macht also referred to Foxx as “Jimmy” in his second volume.

Macht also makes a reference to Fort McKinley at one point, where surely he meant Fort McHenry since he was writing about “bombs bursting in air.”

“The Grand Old Man of Baseball” is a lively, descriptive and poignant end to the career of Connie Mack. He managed in 7,755 games, including 7,466 with Philadelphia from 1901 to 1950. He won nine American League pennants and went to eight World Series (his first pennant in 1902 predated the Series by a year), winning five of them.

But in the end, Macht writes, “the measure of Connie Mack’s life is not the number of pennants or games won and lost but the lasting effect he had on the men he managed and the minds and hearts of those whose lives he touched.”

Mack’s effect was far-reaching. So, too, is Macht’s treatment of Mack’s career.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed