Sound like 1968? You bet. In ’68 Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. The inner cities were rocked by rioting and looting. The Vietnam War basically toppled a president, and a Democratic convention to try and pick a candidate to succeed him degenerated into clashes between Chicago police and antiwar demonstrators. Even sports was not immune, as Olympic track medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised gloved fists on the medal stand during as the national anthem played.

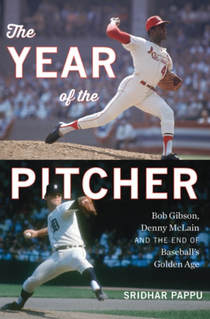

“The bold America that had emerged from World War II was on the verge of cannibalizing itself from within,” Sridhar Pappu writes in his new book, The Year of the Pitcher: Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and the End of Baseball’s Golden Age (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $28; 381 pages). Pappu, “The Male Animal” columnist for The New York Times, deftly trains social and political lenses on 1968, weaving in the results of an extraordinary baseball season that ended with a memorable World Series victory by the Detroit Tigers.

There was some great baseball taking place — well, there was some great pitching — and the two catalysts that year were Bob Gibson and Denny McLain.

Gibson, Pappu writes, was college-educated, “endured injustice, and helped direct change within the culture of the Cardinals.” He was fearless on the mound and when prompted, was not afraid to give his opinion. McLain was a man “brazenly out for himself,” who coveted money and was not afraid to talk about it. “He lived life on the edge” but “never doubted his invincibility.”

Look at Gibson’s stats for 1968. He went 22-9 with an eye-popping 1.12 ERA and 13 shutouts. In Game 1 of the 1968 World Series he struck out a record 17 batters. What’s even more amazing is that the right-hander lost nine games that season; he started 34 games and completed 28 of them. In the 22 games he won, Gibson’s ERA was 0.57. Right-handed hitters managed a .159 average off Gibson; lefties fared slightly better, at .220. In games where the Cardinals scored two or fewer runs, Gibson went 9-8. After all, it’s hard to win if your team doesn’t score. “Gibson had to throw shutouts to win,” Pappu writes. “He was on his own.”

Sridhar Pappu

Sridhar Pappu

I hesitate to call 1968 the end of baseball’s Golden Age, as Pappu implies in his book title. Depending on one’s perspective, the Golden Age can vary in one's interpretation. Some might argue that the post-World War II-expansion era from 1946 to 1960 deserves that title, while others might argue that baseball in the 1920s and ’30s was more appropriately golden. If you’re a Boston Red Sox fan, then 2004 through 2013 might be considered golden. It's arbitrary. What did end was pennant winners decided by most wins during the regular season; 1969 brought the dawn of divisional play and the pitcher’s mound was lowered by five inches, which altered the game.

Pappu tells the story of 1968 through the eyes of the participants, blending baseball with of race, violence, protest and the changing dynamic of American society. He does a nice job with the background leading up to that season. In 1967, summer riots in cities like Detroit and Newark would “forever change” how Americans viewed their urban centers. Pitchers like Mickey Lolich and Pete Richert were forced to change from baseball uniforms to National Guard gear, as they were called up for duty in the smoldering inner cities.

The ’68 season had begun under a cloud, as major-league owners and players grappled over how to respond after King’s assassination in Memphis on April 4. It continued with Kennedy’s death in early June. Meanwhile, pitchers like Gibson and McLain were racking up wins, pointing their teams toward an inevitable confrontation in the World Series. Don Drysdale also etched his name in history in 1968, when he threw 58 2/3 shutout innings.

Pappu blends him some sidebar stories, too. Among them is expertise of Detroit pitching coach Johnny Sain, who kept McLain focused and further enhanced his own reputation as the pitching guru of the 1960s. The experiences of sportswriter George Vecsey and pitcher-turned-author Jim Bouton also add texture to his narrative. In his own book, Ball Four, Bouton would write glowingly of Sain, who produced pennant-winning staffs for the Yankees and Twins before guiding the Tigers to a flag. Pappu adds more to Sain’s legend.

The story of Jackie Robinson, whose influence in American society had begun to wane by 1968, is also told in the context of that difficult year. To the end, Robinson was a crusader — not only for baseball, but for human rights and dignity— Pappu shows why Robinson remains revered today.

The 1968 World Series — billed as Gibson vs. McLain — is retold in great detail. Gibson won twice, but lost Game 7 to Lolich and the Tigers in a memorable finish. Detroit, trailing 3-1 in the best-of-seven series, swept the last three games to win their first World Series since 1945. McLain lost two games but did win Game 6.

There are a few glitches in Pappu’s narrative. In his epilogue, Pappu references a game against Boston where McLain, “on sheer guts,” struck out Cleon Jones, Carl Yastrzemski and Ken Harrelson. Pappu had the wrong Jones; Cleon played for the Mets, while Dalton Jones was with the Red Sox. That 4-0 victory at Fenway Park on Aug. 16, 1968, and those three consecutive whiffs helped McLain earn his 25th win, kindling beliefs that 30 wins were within reach. Those three strikeouts, with runners on second and third in the sixth inning, preserved a 2-0 lead by Detroit.

Pappu also writes of NFL running back “Gayle Sayers” instead of “Gale,” and refers to Bill White as president of the American League, instead of the National League.

These are minor mistakes. The overall effort is excellent, and the contrast between Gibson and McLain remains to this day. Gibson “remains the avatar” of his era and the one baseball fans remember. As for McLain, “the racy headlines have supplanted our memories” of his baseball career.

At a thrift store recently, I stumbled across a 1969 vinyl record album by McLain, touting his ability on the Hammond organ (“Denny is a strong-willed, impulsive man who speaks his mind bluntly,” the liner notes read). I bought the album — with McLain’s autograph (allegedly) scrawled across the cover — for five bucks. It’s easy listening, a mixture of jazz and rock. His favorite song from the 12 he recorded? “Lonely is the Name.”

It’s appropriate.

For one season at least (he did pitch well in others), McLain’s name was up there with the greats. Gibson’s name and feats endure, and he is in the Hall of Fame. Pappu brings both diverse personalities together and gives the reader an entertaining history lesson in The Year of the Pitcher.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed