The two men stood on the field behind a fence and answered questions — here it was, 1977, and the first question to Mantle was about Jim Bouton’s 1970 book, Ball Four — Mantle did most of the talking. Maris, who owned a beer distributorship in Gainesville, remained mostly quiet.

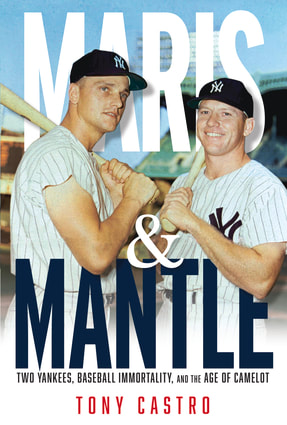

Perhaps that is the perfect analogy for Tony Castro’s latest book, Maris & Mantle: Two Yankees, Baseball Immortality, and the Age of Camelot (Triumph; $28; hardback; 297 pages). Castro has written several books about Mantle, including 2019’s Mantle: The Best There Ever Was, 2016’s DiMag & Mick: Sibling Rivals, Yankee Blood Brothers and 2002’s Mickey Mantle: America’s Prodigal Son.

Castro also wrote the 2018 book, Gehrig & the Babe: The Friendship and the Feud, about Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth, the original deadly tandem in the Yankees lineup.

This month marks the 60th anniversary of Maris’ record-breaking 61st home run, hit at Yankee Stadium off Tracy Stallard into the right-field seats. It is the perfect time to revisit Maris — and Mantle — without the romanticism of calling it “a simpler time,” because that summer was fairly complicated for Maris. A quiet man who shunned the spotlight, Maris, gifted with a strong arm and that picture-perfect swing tailored to Yankee Stadium’s short porch in right field, endured unbearable scrutiny for his time. As Castro writes, the perception that this pressure “broke” Maris that year was merely a great hook for sportswriters as the right fielder chased Babe Ruth’s “unattainable” record all season.

“That kind of superficiality shows just how little the sportswriters … truly knew the man — or how they just failed to understand that it was that very pressure that had historically brought out the best in Roger Maris in personal circumstances far greater than the chase of a home run record.”

Maris was more than a one-dimensional player. His powerful throw kept the San Francisco Giants from scoring in the ninth inning of Game 7 of the 1962 World Series. Willie Mays doubled to right field, but Matty Alou, who was on first base after a bunt single, was forced to stop at third base because of Maris’ relay. The play most historians recall happened next, when second baseman Bobby Richardson snared Willie McCovey’s line drive to preserve a 1-0 victory and give the Yankees a World Series victory.

Still, imagine if ESPN, Twitter and podcasts had been around in 1961. The strain — perceived or real — could have been worse for Maris.

If there is a weakness to Maris & Mantle, it is that the book is heavily tilted toward Mantle. Every author worth his or her salt who has written about the post World War II Yankees have included all the stories about Mantle, and Castro recounts the obligatory anecdotes. Mind you, I enjoy reading and rereading them; whether people who did not cherish the Yankees or Mantle felt the same way is a matter of debate.

I wanted to know more about Maris, but in fairness, Castro dug out as much as he could about the reluctant star. Castro benefited from the kindness of fellow author Peter Golenbock, who sent him a copy of unreleased material from his 1973 interview of Maris.

Castro never had the chance to have the relationship with Maris that he did with Mantle. He had been assigned to follow Maris around during the mid-1980s, but the former player was receiving treatments for the cancer that would kill him in December 1985. So, that never happened.

The book has extensive memories from Holly Brooke, who was Mantle’s “love of his life” during his rookie season in 1951 and beyond. Her memories added more depth to Castro’s work; Brooke had been elusive for years, but a friend connected her to Castro in 2006 and that started a wonderful flow of information from a source who knew Mantle intimately.

But Maris is who I wanted to learn more about, and Castro does a good job in bringing out his parents’ turbulent marriage, his eastern European heritage (Croatian ancestry), and the reason why he changed his last name from Maras.

Maris was not content to bow to the wishes of baseball executives, a trait that could be traced to his high school days. As a minor leaguer, he demanded — and got his wish — to play near his North Dakota home.

“He would either play for Cleveland or Fargo or not at all,” Castro writes.

The decision had nothing to do with money. Maris wanted to stay close to his girlfriend, Pat, who he would eventually marry.

hen Maris was benched by his football coach at Fargo Central High School, Castro writes, he “especially took it personally” and demanded to play or he would transfer to another school. When the coach refused to comply, Maris and his brother transferred to Fargo’s Sacred Heart Academy.

“I have never been the type of person to let anyone give me the business,” Maris would write in his memoir years later.

Castro notes that many of Maris’ friends believed that hostility against the player was exaggerated.

“In re-examining Roger’s life, this is a common thread that runs through his personal narrative,” Castro writes. “An incessant paranoia that the world, or someone in it, would is out to get him and the need to fashion, if not a new identity, then at least something different than the real one.”

Mantle was loved by his teammates, and Maris was certainly respected. That did not seep through in the sports reporting back then; indeed, Castro writes, reporters tried to pit the two stars in a feud during the 1961 season. They were the “imperfect pair of buddies” during that season, previewing the counterculture of the 1960s. The supposed rivals, meanwhile, roomed together in a Queens apartment as the home run race heated up.

Mantle was “the hard-drinking, devil-may-care slugger,” while Maris was “moody, petulant and seemingly angry at much of the world,” Castro writes.

This sets up Castro’s best line in the book.

“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would have only one thing they didn’t; they robbed banks,” Castro writes. “But Mantle and Maris would steal the hearts of American sports in their few brief years together.”

Mantle was loved, but Maris was “the all-business ballplayer ideally made for the corporate image of the Yankees.” Roger was more like Joe DiMaggio than the man who replaced the Yankee Clipper in center field: Coldly efficient, private, and a man who did not suffer fools easily.

In his 1962 memoir, Roger Maris at Bat, Maris wrote that “if people are going to like me, they are going to have to take me as I am. If they don’t like me, then there’s no way I can change them. In fact, I wouldn’t even make an attempt.”

Not everyone was enamored with Maris. Bouton wrote in Ball Four that Maris was one of “the great non-hustlers of all time,” who ran to first base “like he had sore feet.”

But when Maris’ home run record was challenged by Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998, even Bouton softened his position, saying he was “ambivalent” about the home run record tumbling.

“It was not the angry Roger of Ball Four that I was pulling for,” Bouton wrote in his epilogue to Ball Four that was published in 2000. “But the small-town kid from Fargo, North Dakota, who had signed out of high school, and never had help dealing with the big city media.”

Castro draws from many sources, including his own notes and interviews. That includes conversations he had with Mantle’s widow, Merlyn, which he promised to keep confidential until she died. Merlyn Mantle passed away in 2009, and several years later Castro unearthed his notes and used them, along with other material that was not included in his previous works on Mantle.

The Mantle narrative is good, but to me, it was Maris who was the most intriguing character in Maris & Mantle. Many book titles about Mantle reference him being a hero or the best ever, and many are written with reverence and awe.

Mantle deserved that on the field. He was my favorite player when I was growing up, and his off-the-field charades did not matter to me — mainly because they were not reported.

As for Maris, the title of Tom Clavin and Danny Peary’s 2010 book, Roger Maris: Baseball’s Reluctant Hero, is poetically appropriate.

But a decade later, Castro gives Maris the attention he has deserved. Maris would not have cared during his lifetime about the limelight; he was content to stay quietly in the background, just like he did that day in 1977 at the University of Florida when he watched Mantle field question after question.

Maris had seen the glare of publicity before. Allowing someone else to enjoy the spotlight was fine with him.

“As a ballplayer, I would be delighted to hit 61 home runs again,” Maris said shortly after breaking Ruth’s record. “As an individual, I doubt if I could possibly go through it again.”

Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris were such a fearsome duo that when the Yankees also acquired Johnny Carson it really wasn’t even fair anymore. pic.twitter.com/DFg0NTMfay

— Super 70s Sports (@Super70sSports) May 4, 2021

RSS Feed

RSS Feed