Ruth’s record was toppled by Hank Aaron, who in turn was topped by Barry Bonds. But don’t look for any player, any time soon, to break Ripken’s mark of 2,632 consecutive games played. A player needs to be lucky, good, and impervious to pain to achieve a mark like that — plus, he needs a manager who is willing to put his name on the lineup card every day without fail. Most managers now believe in resting players and do not want to risk injury from the fatigue that inevitably comes from playing so many games in a row.

It is a credit to Ripken’s endurance and competitiveness that he not only played so many games in a row, but also remained a productive member of his team. The same can be said about Gehrig.

There have been plenty of books written separately about Gehrig and Ripken; earlier this year, Richard Sandomir wrote about the 1942 film tribute to the Iron Horse in his book, The Pride of the Yankees.

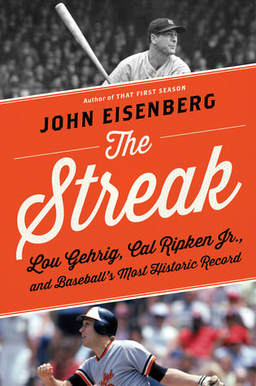

But longtime Baltimore sportswriter John Eisenberg takes a fresh angle, putting Ripken and Gehrig side by side for an absorbing comparative study. In The Streak: Lou Gehrig, Cal Ripken Jr., and Baseball’s Most Historic Record (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; hardback; $26; 299 pages), Eisenberg uses excellent research and a smooth narrative to educate and entertain the reader. Gehrig and Ripken are the main subjects in the book, but Eisenberg delves into history with richly detailed prose that includes some quirky stories about consecutive-game streaks in major-league baseball history.

Ripken broke Gehrig’s record on Sept. 6, 1995, at Baltimore’s Camden Yards, and that’s how Eisenberg opens The Streak. Eisenberg, who covered the Orioles for the Baltimore Sun and saw most of Ripken’s career, is uniquely a Baltimore guy. He wrote for the Sun for two decades, currently contributes columns to the Baltimore Ravens’ website, and still lives in Baltimore. His perspective about Ripken is unique and refreshing.

Eisenberg interviewed 26 people for this book, including Ripken. He also spoke with other players who had consecutive streaks of note, including National League record-holder Steve Garvey and Billy Williams, whose record he broke. Eisenberg also gleaned quotes from five members of the Orioles thanks to research for 1999’s From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, one of nine books he has written.

What emerges is the sheer doggedness of both men. While it’s true that Gehrig once opened a game at shortstop and batted leadoff to preserve his streak, that does not diminish his achievement. Gehrig also was fortunate to receive a few breaks when he was injured; one time, a game was rained out to preserve his record. According to records Eisenberg quotes from Raymond J. Gonzalez of the Society for Baseball Research, Gehrig was relieved by a pinch hitter eight times, by a pinch runner four times, and by a defensive replacement 64 times.

Ripken, meanwhile, started every game of his streak, and unlike many modern players he did not used a pinch-hitting appearance or appeared as a defensive replacement to prolong his streak. What is even more mind-boggling, though, is that Ripken once played in 8,264 consecutive innings before missing the final two innings of a Sept. 14, 1987, game. His replacement was Ron Washington, who would later manage the Texas Rangers to back-to-back American League pennants in 2010 and 2011.

Some of the quirky stories Eisenberg unearths include how an injured Stan Musial kept his streak intact by not actually playing in the game, but by simply being written on a lineup card. Everett Scott, whose record of 1,307 straight games was broken by Gehrig, once paid a man to drive him from a desolate area in Indiana to a trolley in South Bend, Indiana, where he would take a trolley to reach Comiskey Park in time to get into that day’s game.

Eisenberg also revisits the story of George Pinkney, who held the 19th century mark of 578 consecutive games from 1885 to 1890. Pinkney’s feat was buried for several years but was rediscovered when Fred Luderus played in more than 500 straight games during the last few years of the dead ball era. Scott would break Pinkney’s record on June 21, 1920.

Despite Eisenberg’s wonderful and detailed research, there are a few glitches. He refers to the Washington Senators winning the American League pennant in 1932 (they won it in 1933), and writes that the Boston Red Sox faced the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1918 World Series (the Sox faced the Chicago Cubs, although Boston and Philadelphia met in the 1915 World Series). He also writes that Joe DiMaggio played four full seasons with Gehrig, when he in fact played three (1936, 1937 and 1938 — Gehrig only played eight games in 1939 before benching himself).

From a stylistic standpoint, the only bump appears to be Eisenberg’s penchant to note that a certain player was “interviewed for this book.” It’s important, I suppose, to let the reader know that a certain player spoke to Eisenberg — at least from a credibility standpoint. But Eisenberg earned his writing and integrity chops long ago, so while it seemed necessary to make the point, it just did not read smoothly. Perhaps mentioning the people whom he quoted outside of the interviews he conducted would have worked better. It’s not worth quibbling about.

The Streak is an enjoyable read, full of history and anecdotes, lively quotes and a narrative that bounces between Ripken, Gehrig and other players who achieved ironman status during their careers. Gehrig’s record seemed unbreakable when he set it; Ripken’s now seems even more formidable. It probably will stand for all time.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed