The San Francisco Chronicle has called Averell “Ace” Smith “a pro at digging up dirt,” and one of the country’s most feared political opposition researchers. His critics have called him experienced, bright and aggressive, but “frequently over the top.”

Smith has been a political strategist and a campaign manager. He worked on the mayoral campaigns of Chicago’s Richard M. Daley and Los Angeles’ Richard Riordan, and the presidential campaigns of Hillary Clinton in 2008 and Howard Dean.

So, Smith not only can get down and dirty, but he also can spin a compelling story.

That serves Smith well as he tackles a subject that blends baseball with politics. And during the 1930s, and for very different reasons, few men were more feared, over the top and unafraid to get down and dirty than pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige and Dominican Republic strongman Rafael Trujillo. While Paige’s fastball was described as having bulletlike qualities, Trujillo’s bullets came from real guns and he was not afraid to give the order for his men to shoot them.

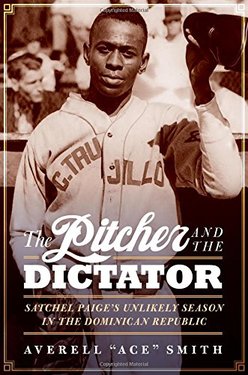

Those two characters dominate Smith’s book, The Pitcher and the Dictator: Satchel Paige’s Unlikely Season in the Dominican Republic (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $26.95; 212 pages). Baseball plays a large role in Smith’s work, but the more fascinating subplot concerns the politics and intrigue waged by Trujillo, known as El Jefe (The Chief), who rose to power in 1930 and remained entrenched as the Dominican Republic’s most dominant figure until his assassination in 1961.

Trujillo was smart enough to keep a tight rein over his government and canny enough to take advantage of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy” during the 1930s. Because of the growing threat of Nazi Germany, Roosevelt wanted Western Hemisphere countries as allies and conveniently looked the other way if they committed any atrocities. As Eric Paul Roorda wrote in 1998, the Good Neighbor Policy showed Latin American dictators like Trujillo that they could run their governments any way they wanted, so long as they had the same enemies as the United States.

Paige, meanwhile, was an opportunist not afraid to jump teams if the money was right. One example was nicely documented in Tom Dunkel’s 2013 book, Color Blind, when Paige bolted from the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords to pitch for a team in Bismarck, North Dakota, in 1935. So, when Dr. Jose Enrique Aybar, a dentist who ran the baseball team in Ciudad Trujillo, approached Paige with a $30,000 offer to pitch in the Dominican Republic in 1937, Paige bolted again, jumping as soon as he saw a bankbook with his name on it and that the five-figure deposit was verified in his account.

Aybar’s opening bid was “meant to awe,” Smith writes. “And it did.”

Finishing in second place was unacceptable; Trujillo, who could be called a military version of Leo Durocher, was not interested in sportsmanship: “I come to kill ya,” the Lip wrote in his autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Last. Trujillo was cut from the same cloth, with more lethal means to pursue his goals. He was interested in winning, and his representatives made that clear to Paige and his teammates. This was not just a game; by wearing a uniform with Trujillo’s name on their chests, they were representing the prestige and honor of the dictator, who did not take kindly to being cast in a negative light.

“You better win,” the players were chillingly told.

Despite Trujillo’s repressive dictatorship, Paige and other black players found the island to be much more progressive in race relations than in the Deep South of the United States. Paige and his favorite catcher, William “Cy” Perkins, walking through Ciudad Trujillo, “were amazed to see folks white, black, and everything in between” mingling together. It was a far cry from being refused service at restaurants in Mississippi or Alabama. So, while Paige and his teammates enjoyed the easy living, they started to lose. And that did not sit well with Aybar, who knew what Trujillo’s reaction would be.

Fortunately, for Paige and his teammates, they regained the winning touch and won the tournament, then, richer for their efforts, barnstormed in the United States wearing the Ciudad Trujillo uniforms.

As one might expect, Smith’s research is meticulous and thorough. His bibliography includes a wealth of books that encompass baseball, race, social issues and history. Smith also combed through journals and newspaper articles in the Dominican Republic, including Listin Diario; his research also was drawn from black newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Defender and Afro-American. For The Pitcher and the Dictator, Smith looked through microfilm and microfiche to give texture to the Jim Crow era of the South.

In politics, Smith’s opposition research techniques saw him buried deep in libraries, sifting through documents. Smith was feared because he could ferret out damaging information about an opposition candidate. If there were skeletons in a candidate’s closet, Smith was certain to be knocking on the door.

The Pitcher and the Dictator is an entertaining read, and Smith goes to great pains to describe the mood, the weather, the fans’ enthusiasm and the sinister specter of Trujillo looking over the all-stars’ shoulders. The detail is exquisite.

The book’s importance is not only in defining race relations and Caribbean gunboat diplomacy, but also lifting another veil from the shrouded legend of Satchel Paige. The mercurial Paige was a master showman who knew how to market himself, but he always maintained an air of mystery that baseball fans found irresistible.

Smith shows that Paige was not always infallible on the mound, but still commanded a presence among baseball fans. Works like Smith’s — and Dunkel’s before him — are valuable slices of baseball history that are worth the read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed