Dr. Martin Luther King was one of those pioneers. So were Ralph Abernathy, Julian Bond, Rosa Parks, and athletes like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and Muhammad Ali.

Add St. Petersburg physician Ralph Wimbish Sr. into that group.

Wimbish’s actions in his hometown helped desegregate lunch counters, integrate hospitals and golf courses, and, significantly for athletes, help eliminate the Jim Crow laws that kept white and black teammates from staying in the same hotels and eating at the same restaurants.

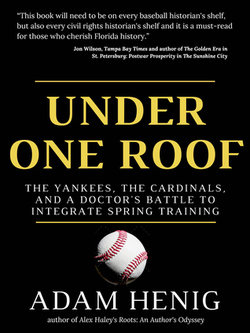

Wimbish’s story is told, albeit briefly, in Adam Henig’s second book, “Under One Roof: The Yankees, the Cardinals, and a Doctor’s Battle to Integrate Spring Training” (Wise Ink Creative Publishing; paperback; 132 pages, $9.95). This self-published book is only 100 pages long (not counting notes and acknowledgments), but Henig does a nice job tracing the career of a man who would not be denied.

The central theme of “Under One Roof” is how Wimbish worked to ensure that black baseball players who came to St. Petersburg for spring training would be able to live and eat in the same places as their white teammates. The St. Louis Cardinals had three black stars in Bob Gibson, Bill White and Curt Flood. The New York Yankees had Elston Howard, Hector Lopez and Jesse Gonder. All of them were forced to live in residences of black families, and not in the segregated hotels that housed their white teammates.

Henig opens the book with a story about author Alex Haley, who was on assignment for Sport magazine to write about segregation at spring training. Arriving in St. Petersburg, Haley was met by White, a star first baseman and future National League president.

“You fly down here hot to do a story to show what segregation’s like on a ball team,” White told Haley. “There isn’t any segregation on the team. The segregation is in St. Petersburg — and Florida.

“That’s the story!”

Wimbish intended to change that story. A distinguished family physician, Wimbish believed that racism could be defeated through “covert means,” self-control, and money out of his own pocket if necessary. He graduated from Florida A&M in 1946 and then from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1950.

Wimbish’s “booming voice” made him a leader in the black community (he was president of the local NAACP chapter), and even a cross-burning on his front lawn in 1956 did not deter him. Wimbish helped integrate restaurants at Howard Johnson motels and the Maas Brothers department store, and waged a long battle to integrate Webb’s City, “The World’s Most Unusual Drug Store.”

There was a “red line” in St. Pete, whose borders were 6th and 15th Avenues South, west of 17th Street South. Blacks were basically barred from living or running businesses outside that perimeter until 1954, when St. Petersburg dentist Robert Swain challenged the city it refused to issue building permits for an office he wanted to open at 1501 22nd St. South. The city backed down when legal action was threatened.

The next step was to hit St. Petersburg in the wallet. Baseball was the economic spark for the city, with two major-league teams drawing thousands of customers for games. Out-of-state fans ate at restaurants and stayed at hotels in St. Petersburg, so the economic impact was enormous. In January 1961, Wimbish decided the time was ripe to put the squeeze on the city that depended upon the Grapefruit League every spring. He met with St. Petersburg Times sportswriter Jack Ellison and announced that housing segregation would not be tolerated — and discontinued.

Easier said than done, of course. Another cross was burned on Wimbish’s yard, and another controversy was sparked when black players were left off the list of invitees for St. Pete’s annual “Salute to Baseball” breakfast. Bill White was especially miffed about the snub, and despite his denials years later, that had to be a factor in his opposition for a major-league franchise in the Tampa Bay area in the 1990s. He helped block the Giants’ proposed move to St. Petersburg (it had seemed like such a “done deal” that the Tampa Tribune and St. Petersburg Times put out special sections welcoming the Giants), and when the area was finally awarded a major-league team, it was from the American League.

Wimbish died too soon, at age 45 in 1967, to see some of the progress that has been made in racial issues. While Henig notes that Wimbish doesn’t even have a Wikipedia entry, it should be noted that his wife, C. Bette Wimbish — who died in 2009 and was a crusader in the same vein as her husband — does. Bette was the first black member of the St. Petersburg City Council, elected in 1969, and later was the city’s vice mayor.

Henig uses several sources in “Under One Roof,” including interviews with Wimbish’s children; White; and Elston Howard’s widow, Arlene. The spark for this book was ignited by an article written by Tampa Tribune correspondent Michael Butler on May 9, 2015, and also from the assistance of former St. Petersburg Times reporter Jon Wilson, who retired in 2007. Newspaper and magazine articles also add to Henig’s narrative.

“Under One Roof” is a story of courage and determination that needed to be told. National civil rights figures have received a great deal of credit — and deservedly so — but men like Wimbish were working hard at the grassroots level to eliminate hatred and racism.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed