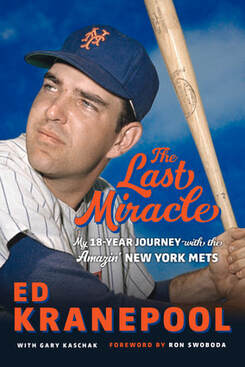

The nickname is a tribute to Kranepool’s consistency, and also his demeanor as he withstood the Mets’ early growing pains, enjoyed their miracle 1969 season and then endured some lousy seasons after the “You Gotta Believe” pennant-winning season of 1973.

My father, a big Mets fan when my family lived in Brooklyn, New York, during the 1960s, twisted that consistency to some extent. To this day he notes that batting left-handed, Kranepool would “hit a two-hop ground ball to the first baseman” every time he connected.

This is of course, an exaggeration. Kranepool collected 1,418 hits during his major league career. For context, my father also used to complain about “how terrible” the 1972 Miami Dolphins were after every game when we lived in South Florida during the 1970s. “Did you see the Dolphins? They were terrible.”

Yes, the worst team in NFL history with a perfect record. And the only one.

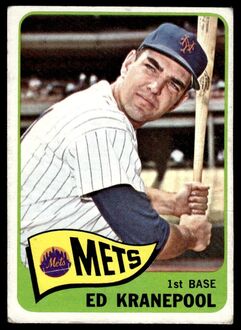

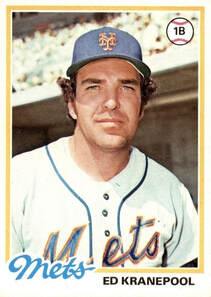

Those are the kinds of expectations that Kranepool faced. He was an all-star at age 19 during the 1965 season when he wore No. 7 for the first time, which in New York meant Mickey Mantle and the Yankees. And Kranepool grew up in the Bronx, too, rooting for the Yankees and Mantle.

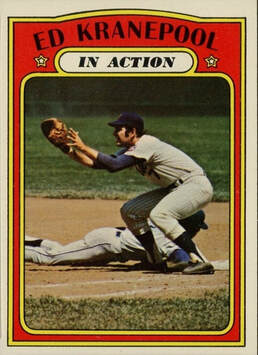

Kranepool chronicles the ups and downs of his career. He chafed at being platooned and being labeled a role player, but he also excelled. In 1974 he set the all-time season record for average by a pinch hitter with 30 at-bats or more when he hit .486. During his career, Kranepool would collect 90 hits — including six home runs — off the bench.

Kranepool grew up playing baseball in the Castle Hill Playground in the southeastern section of the Bronx, “a melting pot of race, religion, color; you name it.”

He also grew up without a father. Sgt. Edward Emil Kranepool Jr. was killed World War II at Saint-Lô, France, on July 28, 1944, nearly four months before his son was born. The elder Kranepool was 31.

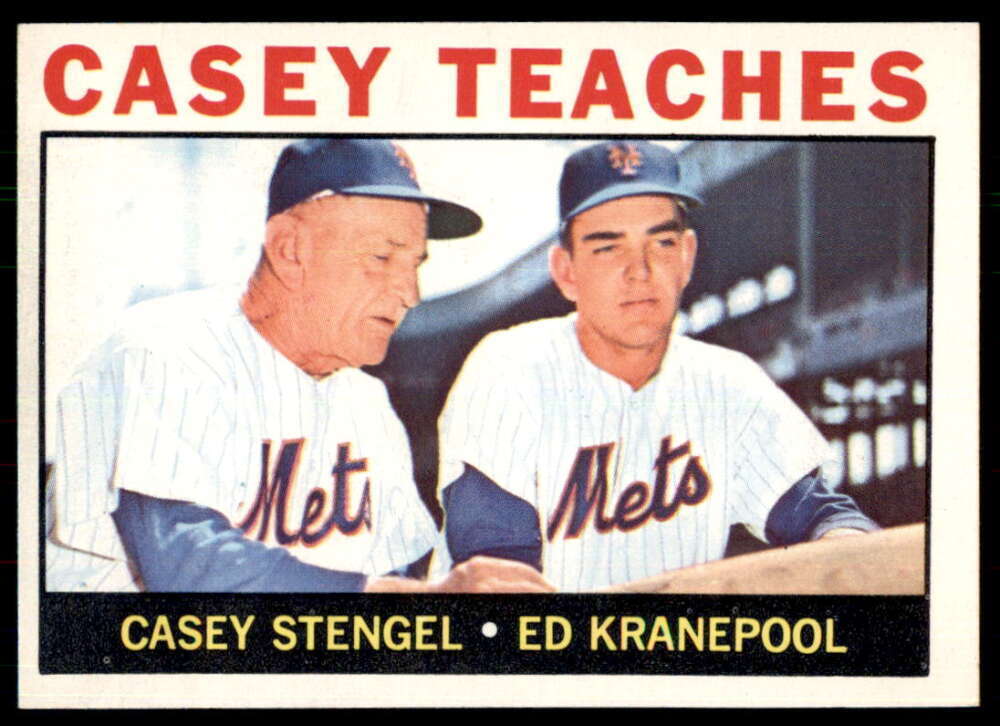

Kranepool has a unique perspective about the Mets, since his career began during the team’s infancy. He watched as Casey Stengel deflected the team’s miserable play and put the focus on himself as the franchise brought in over-the-hill players who still had marquee value.

“He’d battle for you and protect you and take all the heat from the press when he had to,” Kranepool said.

Kranepool is candid in his belief that he was promoted to the majors too quickly, that he needed more seasoning “physically and mentally.” Because of his age, some of Kranepool’s teammates were twice his age, and he concedes that the Mets “force-fed me to the major leagues.” Not that he objected at the time, but an older and wiser Kranepool understands now how more time in the minor leagues would have helped his development.

Besides, he saw some bizarre things with the Mets: Jimmy Piersall running backward for his 100th career home run; witnessing a no-hitter on his first day as a major leaguer (Sandy Koufax won a 5-0 gem on June 30, 1962), and watching a triple play on the final day of the ’62 season (the Cubs pulled off the triple-killing in the eighth inning at Wrigley Field to stifle a rally and preserve Chicago’s 5-1 win – and clinch New York’s 120th loss of the season).

He credited Hodges for teaching him “so much about the game and being a man” and wishing he had been his manager early in his career.

But the relationship was not always smooth.

Kranepool had an outburst against Hodges in 1968 after going 0-for-3 against Chris Short in a Sept. 21 game at Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia. After he was lifted for a pinch hitter, Kranepool said he told Hodges, “if you’re so smart, you should have done it four hours ago.”

Bad move. Hodges kept him on the bench for the rest of the season, except for a pinch-hitting appearance on Sept. 27 in which he struck out.

“I could have kicked myself for mouthing off because then I spent the whole winter wondering if I was gonna get traded or if they’d acquire another first baseman,” Kranepool writes.

But when Kranepool got into a scrap with infielder Tim Foli in 1970, Hodges took his side.

“Hodges wasn’t the kind of manager who’d actually say things are good now,” Kranepool writes. “But I knew that as long as I performed and didn’t mouth off, from that point on, he was in my corner.

“Hodges made a difference,” Kranepool said on the eve of his former manager’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022. “He was the leader we sorely needed.”

Kranepool brings the reader into the locker room for the Mets’ unlikely run to glory in 1969 and spins warm, funny stories along with great detail about the games.

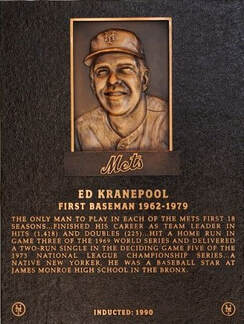

He hit a home run in Game 3 of the 1969 World Series and would deliver a key two-run single in Game 5 of the 1973 National League Championship Series.

He also writes about an April 4, 1979, skit on Saturday Night Live, when he participated in a spring training “interview” with Bill Murray about fictional baseball player Chico Escuela (played by Garrett Morris in halting English – “baseball been berry good to me”) and his “controversial” book, Bad Stuff About the Mets.

“Well, you know Chico was a pretty good player for us in ’69 and ’73, but that book he wrote – a couple of us got hurt pretty bad from that,” Kranepool deadpans. “He shouldn’t have wrote it.”

He also debunks Escuela’s contention that Tom Seaver “always take up two parking places” and that Kranepool “borrowed Chico’s soap and never give it back.”

“He was nothing but a negative person, and I didn’t think what he did was funny,” Kranepool writes.

Kranepool said he also “held resentment” against Gene Mauch, who managed the National League in the 1965 All-Star Game and “hardly substituted at all,” meaning the Mets’ all-star watched the entire game from the bench.

The NL won the game 6-5 and had a roster containing 13 future Hall of Famers.

After that, “I tried to beat him, I tried to impress him,” and at the end of his career, when Kranepool received a telephone call from Mauch about possibly playing for Minnesota, he turned him down and retired instead.

“I held a grudge until the day I retired,” Kranepool writes.

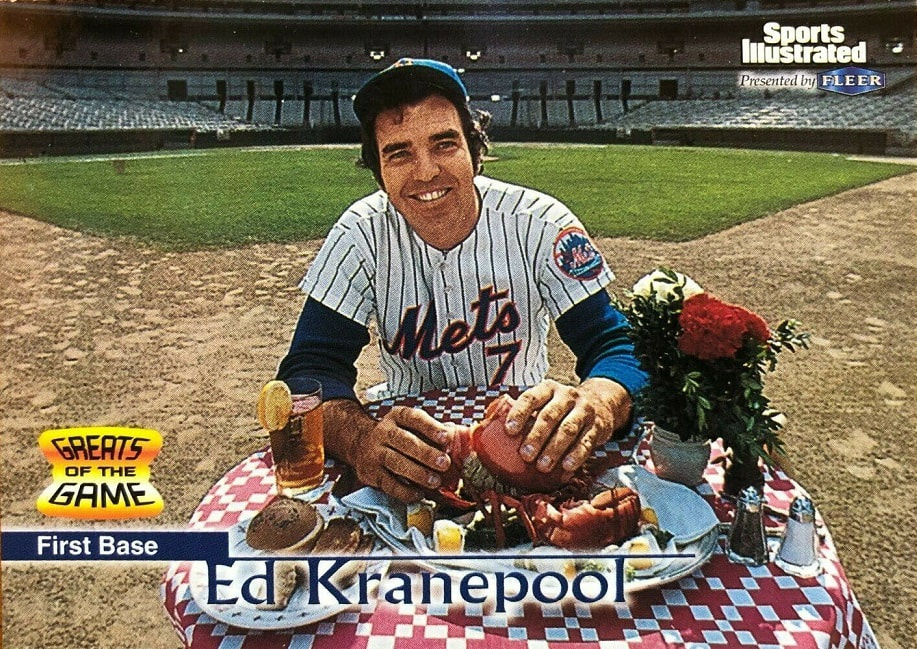

He would dabble in the restaurant business with teammate Ron Swoboda (who wrote the foreword to Kranepool’s book), and was a stockbroker for five years during the offseason.

The blockbuster trade that sent franchise pitcher Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds, in 1977, was unpopular with Mets fans and players. And Kranepool called it a key moment in franchise history.

“That was really the dagger of the many turning points to the Mets’ downfall,” Kranepool writes, placing the blame for the trade on then-general manager Joe McDonald.

Kranepool also has salty words for Joe Torre, his former teammate, roommate and manager. He writes that he had a handshake agreement from his manager that he would be a starter in 1978, but it did not happen.

When Kranepool wanted to be a player/coach on Torre’s staff, he asked the manager to intercede on his behalf with the front office, but “he couldn’t help me,” he writes.

Words were exchanged, and “he went one way, and I went the other way,” Kranepool writes.

“And to this day, I want nothing to do with him.”

Kranepool’s departure from the Mets left a bitter taste. He was 35 and had spent 18 seasons in New York, and the way his career ended “never sat well with me,” as he was never considered for a place in the organization.

“I’d given 18 years and just like that was an afterthought,” he writes.

But health issues pushed those emotions aside. Kranepool had diabetes, three foot surgeries and would require a kidney transplant.

Finding a match for the kidney was a miracle in itself, and Kranepool’s gratitude shines through as he tells an unlikely but heartwarming story that involved a police officer, a firefighter, the fireman’s wife and a retired baseball player.

Then, Kranepool’s wife, Monica, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, a frightening prospect. But six hours of surgery and four more treatments left her without any signs of cancer.

“I’d had my miracle with my kidney transplant, and now my wife had hers,” Kranepool writes.

“We knew we’d be facing Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry and possibly (Sandy) Koufax later on,” he writes.

Koufax retired after the 1966 season, and the only way he would have been in the ballpark was as a color commentator for NBC Sports.

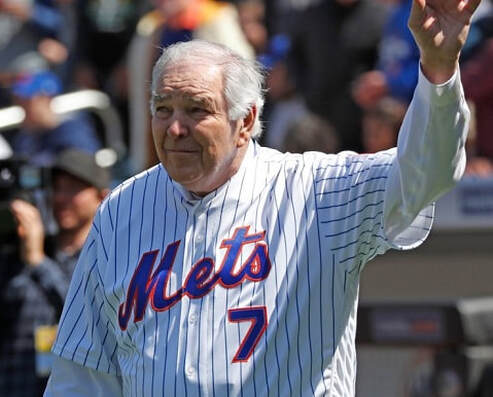

Kranepool eventually healed his rift with the Mets and was inducted into the team’s Hall of Fame in 1990. He also was inducted into the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame in 2013.

It is true, Kranepool writes, that he was a survivor — on the field and off. He was with the Mets when the only entertainment came from Stengel’s ramblings and Bill Gallo’s cartoons in the Daily News featuring the disheveled but loyal fan, Basement Bertha. He tasted sweet victory with the Mets’ World Series win in 1969, even though he was a platoon player, and endured the years of mediocrity after the Mets reached the postseason again in 1973.

He was never traded and still holds several team records, and his health has improved since his kidney transplant.

In a July 7, 1975, feature, Sports Illustrated noted that Kranepool was “more a Met than any other man who has worn the uniform, more than the Throneberrys and Kanehls who made them amazin', and the Seavers and Koosmans who made them successful.”

Truly, Ed Kranepool is the ultimate Met.

“I had my share of miracles on and off the field,” Kranepool writes. “I finally realized that I wasn’t the odd man out. I was the odd man in.”

Steady Eddie forever.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed