We wonder what made this brilliant athlete tick. If he wasn’t baseball’s greatest player, Cobb was certainly among them. The Detroit Tigers’ center fielder was admired for his intense, brainy approach to the game, but he also was feared and despised. What motivated him to be baseball’s greatest player — and biggest draw — in the first two decades of the 20th century?

Some baseball biographers have told Cobb’s story in broad, general terms. He was portrayed as racist, mean-spirited and vengeful. He retired with 12 American League batting titles, a .367 lifetime average (since adjusted to .366) and was elected to the inaugural National Baseball Hall of Fame class. Intense on the field, he once climbed into the stands and beat a handicapped heckler senseless. He also fought with teammates and even duked it out with an umpire after a game.

He always had a chip on his shoulder.

“He came up from the South, you know,” Cobb’s teammate, outfielder Sam Crawford, told Lawrence Ritter in The Glory of Their Times, “and he was still fighting the Civil War.”

That might not be entirely true, but Cobb’s cultural and social upbringing is at the heart of a new book by Steven Elliott Tripp: Ty Cobb: Baseball and American Manhood (Rowman & Littlefield; hardback; $29.95; 402 pages).

“He brought a distinctive social orientation and worldview that was unique to the turn-of-the-century South,” writes Tripp, who teaches social and cultural American history at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Michigan.

This is not a traditional biography. It is, Tripp writes, “a work of social and cultural history.” And it’s a book that brings to the forefront the subject of manhood and defending one’s honor. Ty Cobb was highly sensitive about preserving his honor, Tripp writes. Tripp is not an apologist for Cobb, but he does provide some interesting insights about why the athlete acted the way he did.

Tripp has written about social and cultural issues before, publishing Yankee Town, Southern City: Race and Class Relations in Civil War Lynchburg in 1999. He uses those lenses in prying open the personality of Ty Cobb.

For example, “Cobb understood fully that according to the ethic of Southern honor, he gained status by humiliating his adversaries,” Tripp writes.

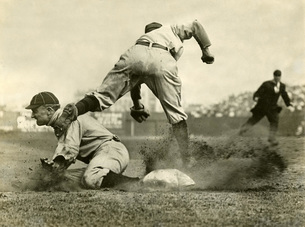

So it didn’t matter whether Cobb was rattling a pitcher by taking a long lead, sliding into second base with spikes high or taking an extra base. If he could intimidate or humiliate an opponent, he would because it gave him that added edge. If he exhibited that same arrogance away from the ballpark, so much the better.

“After each game, he took his usual evening constitutional,” Tripp writes, “even though it meant he had to walk through the large crowds that assembled outside his hotel to scare him.”

Cobb reveled in an environment of “open confrontations and blood rivalries.”

Many authors have taken a crack at Cobb through the years, including the Georgia Peach himself. Cobb collaborated with Al Stump in 1961 for a “setting the record straight” autobiography, and in 1984 Charles Alexander made an earnest but flawed attempt with Ty Cobb. Stump wrote a magazine piece about Cobb after the Hall of Famer’s death in 1961, and then returned in 1994 with the self-serving Cobb. In 2013, Herschel Cobb wrote a warm, sentimental book about his grandfather (Heart of a Tiger). Armed with new research, Charles Leerhsen in 2015 presented a ground-breaking, thorough and compelling view in Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty.

Tripp’s book grew out of an essay he wrote for the Journal of Social History in October 2009, titled “The Most Popular Unpopular Man in Baseball.”

In Ty Cobb: Baseball and American Manhood, Tripp attempts to answer these questions: Why did Cobb act the way he did? And despite his flaws, why was Cobb the game’s most popular player in the first two decades of the 20th century?

Specifically, Tripp argues, “Cobb was the product of his culture.” He was taught at a very early age by his father — a man he revered — never to back down. William H. Cobb “exemplified mastery, authority, will,” Tripp writes. “William was everything Ty hoped to be in a man.”

The fact that Cobb’s father was shot to death by his mother as the baseball player was beginning his major-league career also took its toll. Defending his mother’s honor at the subsequent trial (she was acquitted) epitomized the Southern manhood that Cobb cherished.

In other words, Cobb got along fine with blacks who “knew their place.”

After his retirement, Cobb — who refused to play with or against blacks — accepted the integration as part of the game, but since he made that belief known five years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line, Tripp writes that Cobb “came a bit late to the party.”

Tripp also presents a fascinating look at the dynamic between Cobb and Babe Ruth. Cobb viewed Ruth as an uncouth man who was usurping his place as baseball’s biggest attraction. And it was true: Ruth’s home run skills would change the game and relegate scientific baseball to the back burner.

“Cobb viewed his competition with Ruth as a duel for supremacy, as yet another affair of honor,” Tripp writes.

Tripp utilizes a vast trove of primary and secondary sources in his book, including unpublished writings from the Hall of Fame. The only real glitch comes in a story tells about Heinie Groh in the 1922 World Series. Tripp refers to him as a third baseman for the Reds — which he was — but in 1922 Groh was wielding his famous “bottle bat” for the New York Giants, who appeared in that season’s World Series.

Tripp has presented a different lens to view Ty Cobb. Baseball historians and authors know about his statistics and personality. View have tried to dig deeply beneath the surface to find out why.

“Maybe if he hadn’t had that persecution complex he never would have been the great ballplayer he was,” Crawford told Ritter.

Tripp’s work is a nice complement — and a refreshing, different view — to the volume of works about Ty Cobb.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed