“He’s a higher pay grade than I am,” Jackson wrote back. “Sorry.”

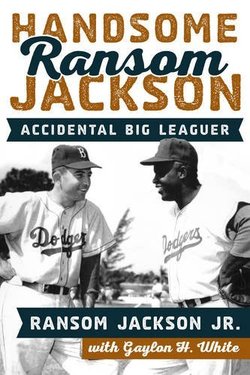

Jackson the baseball player doesn’t mind. He experienced his own journey as a baseball star. In Handsome Ransom Jackson: Accidental Big Leaguer (Rowman & Littlefield; hardback; 262 pages), Jackson, who turned 90 on February 10, recalls his 10-year major-league career with a wistful, nostalgic narrative.

Jackson was the last Brooklyn Dodger to hit a home run and was the first man to draw an intentional walk when that statistic became official in 1955. More trivia: As a college football player, Jackson is the only player to play in back-to-back Cotton Bowls with two different schools (TCU and Texas). He also was a two-time major-league all-star, and has met the famous (Muhammad Ali) and the infamous (he had dinner with a mob boss).

“Handsome Ransom” hit .261 during his career, connecting for 103 homers and 415 RBIs. After his second consecutive all-star season with the Chicago Cubs, Jackson was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1956. Jackson had the unenviable task of replacing Jackie Robinson at third base, but he still did well, playing in 101 games and batting .274. But Robinson was inspired by the competition, entering the 1956 season slimmed down and won the starting job.

“We were competitors, not rivals,” Jackson writes. “We knew the situation and never talked about it.”

Jackson knew what Robinson had done for the game and conceded he had some big shoes to fill when the time came.

“How do you replace a baseball legend and a civil rights pioneer,” he writes. “The answer: you don’t.”

Jackson, with the assistance of former sportswriter Gaylon H. White, offers a fascinating view of his childhood during the Great Depression, his minor-league career and his years with the Cubs. He talks about some of the edges teams tried to get on their opponents. For example, at Wrigley Field, the hand-operated scoreboard “was ideal” for stealing signs. One of the number slots was left blank and a scoreboard operator used his feet to communicate with the batter. One foot meant a fastball and two meant a curveball.

“My eyes weren’t that good,” Jackson wrote, confessing that he had trouble seeing the shoes in the slot. “Needless to say, cheating didn’t make me a better hitter.”

Jackson was never a holler guy. He kept to himself and did his job. Because he was so laid back, he was criticized for not having a fiery disposition and being too mechanical on the baseball field. That was in direct contrast to his first manager with the Cubs, Hall of Famer Frank Frisch. The “Fordham Flash” baited umpires and once was ejected for throwing a book out of the dugout and onto the field. The plate umpire thought it was a rulebook when in fact, it was Quiet Street, a novel about Israel written by Zelda Popkin.

“I’m simply not a rah-rah or fire-and-brimstone kind of guy,” Jackson writes. “I tried as hard as any player who made a lot of noise.”

He didn’t have to. Jackson enjoyed a nice career in the game, and sold insurance after retiring. He led a comfortable life and enjoyed talking about baseball. That’s what makes his autobiography appealing. Jackson tells warm, funny stories about the game and the men who played it. It’s a fascinating look at the game before television became prominent. Jackson relishes the role of storyteller.

“Memories are life, far more important than any scrap of paper,” he writes.

Oh, he’ll sign those scraps of paper if you ask — as long as you ask the right Randy Jackson.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed