An enraged Kansas City third baseman George Brett comes charging out of the dugout, arms flailing, veins popping on his neck. He has to be restrained by umpire Joe Brinkman, who has him in a headlock.

Even Brett’s three sons used to pop in the tape of the Pine Tar Game, and “watch Dad go berserk.”

“They sit around and chuckle,” Brett says.

http://m.mlb.com/video/topic/6479266/v3977861/bb-moments-72483-george-bretts-pine-tar-bat

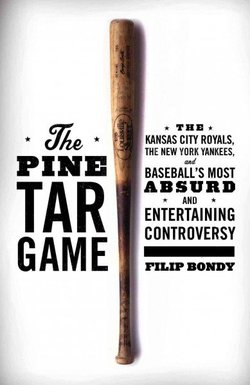

Longtime New York Daily News columnist Filip Bondy puts this wacky 1983 game and its aftermath into perspective in his new book, “The Pine Tar Game: The Kansas City Royals, the New York Yankees, and Baseball’s Most Absurd and Entertaining Controversy” (Scribner; hardback; $25; 246 pages). Bondy, who covered the Yankees in 1983 as a young sportswriter, brings depth and nuance into the rivalry between New York and Kansas City.

The fact that the actual game isn’t reported on until Page 127 is not a detriment. Bondy’s narrative leading up to the pine tar incident is fascinating and illuminating.

The Pine Tar Game wasn’t just an isolated incident, but the boiling point of a feud that was building for nearly three decades. The two cities had been dueling ever since the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City in 1955, and the Yankees continued to treat the team like its former minor-league affiliate in the city, cherry picking stars like Roger Maris, Ralph Terry and Clete Boyer, among others.

The Royals entered the majors in 1969, a year after the A’s bolted for Oakland. By 1976, the Royals began a run of three straight division titles—but were denied a World Series berth each time by the Yankees. Kansas City finally broke through by beating the Yankees in the 1980 ALCS. Brett unloaded a monstrous three-run homer off Goose Gossage in the deciding game to punch the Royals’ first ticket to the World Series.

On July 24, 1983 at Yankee Stadium, Brett had hit what he thought was a go-ahead two-run homer with two outs in the ninth inning off Gossage. Instead, Yankees manager Billy Martin came out and showed the umpires that Brett’s bat, covered in pine tar, had exceeded the 18-inch limit from the bat barrel allowed under the rules.

“If he (Martin) wins this, there will be chaos,” Yankees radio broadcaster Phil Rizzuto said.

The Scooter was right. Martin won it. Brett was called out, the homer was nullified and the game was over. And holy cow, there was chaos after the umpires invoked Rule 1.10(c).

“I looked like my father chasing me around after I brought home my report card,” Brett said.

“Maddest baseball player I’ve ever seen, for sure,” Gossage said. “I was out there laughing my head off.

“I thought it was hilarious.”

Histrionics aside, it became apparent that the obscure rule was well, ridiculous. Once Brett was subdued (the whole incident lasted 130 seconds), the game was protested to the American League office, After 25 days, AL president Lee MacPhail upheld the protest and ordered the game to resume after the home run — with Kansas City leading 5-4 in the top of the ninth. The Royals held on to win, and the Pine Tar Game was history.

Bondy builds this story in “The Pine Tar Game,” layering it with player profiles and history. He writes that Yankees third base coach Don Zimmer alerted Martin to the illegality of the bat. But it’s the chapter after the game that is what sets “The Pine Tar Game” apart from other descriptions. Bondy writes about Dean Taylor, who was the Royals’ assistant director of scouting development in 1983.

After seeing the incident on television, Taylor, a self-proclaimed “sort of a rules buff,” did some research and realized that the penalty for violating Rule 110 was limited to removing the bat from the game. The pine tar did not enhance the distance a ball could travel, like a corked bat might; it simply aided the batter’s grip.

“The light went on over my head and I thought the umpires had misinterpreted the rules,” Taylor said.

It was true, Bondy writes. “The ball had not been struck illegally. It was just the bat that was illegal.”

MacPhail upheld the protest, and Bondy writes that Martin was put “in the extremely unfamiliar position of defending the integrity of umpires.”

The continuation of the game bordered on a farce. Pitcher Ron Guidry was playing center field. First baseman Don Mattingly was shifted to second base. Martin tried an appeal at each base, but each was denied. When Martin tried to protest that this was a different umpiring crew than the July 24 bunch, home plate umpire Dave Phillips produced an affidavit signed by the original crew, stating that Brett had touched all the bases.

Bondy’s characterizations of the rival owners are deadly accurate. Royals owner Ewing Kauffman and Yankees owner George Steinbrenner could not have been more different. Kauffman was “a calm, thoughtful man, Bondy writes, who was advised by his doctor to pursue a hobby — so he bought the Royals. He knew only three songs: “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and “Onward Christian Soldiers.” Steinbrenner was the exact opposite: blustery, bombastic and controversial. Hands-on and meddlesome to a fault.

“If this had been 1776, Kauffman would be Thomas Jefferson to Steinbrenner’s Samuel Adams,” Kauffman writes.

Bondy also peppers the book with mini-profiles, writing about McPhail, Roy Cohn, Rush Limbaugh, John Schuerholz, Dick Howser and Bob Fishel.

Brett, who went on to a Hall of Fame career, is amused by the Pine Tar Game and how he is remembered.

“I played twenty years in the major leagues,” he said. “I did some good things, and the one at-bat I’m remembered for is an at-bat in July, not an at-bat in October like Reggie Jackson.

“Only in New York.”

Bondy has written an entertaining book that captures the excitement, the drama, and the absolute absurdity over the stickiest situation in baseball history.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed